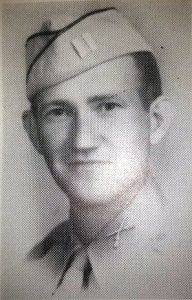

AUBREY RAY BIGGS

In January of 1949, Mr. Quintus Biggs requested a military headstone for his son Aubrey for placement at the McNeil Cemetery. Like thousands of other requests, this application was verified and granted.

Aubrey was the son of “QD” Biggs and Alberta Pauline West Biggs. He was born in the McNeil Community on July 7, 1912. He had two older brothers, Loren Dabney “Chango”, and Roy Lee.

Aubrey graduated from Luling High School and attended Texas A&M. He was a member of Company H, Infantry. His senior year he was a Cadet 1st Lieutenant., He received a degree in petroleum engineering in 1935. He married in 1941 and lived at 212 N. Carrizo, Corpus Christi with his wife Rosalie. He entered the service at Fort Huachuca, Arizona on June 4, 1941, leaving behind a position as a petroleum engineer with Allen and Morris Drilling Company. In 1944, the Newsboy reported that Aubrey’s wife was living with her parents in Corpus Christi for the duration of the war. His parents were living in El Campo, and QD Biggs was working in Bay City.

Aubrey assisted in activating the 92nd Infantry Division in 1942 and then participated in training in Louisiana and Arizona. Aubrey’s unit was shipped overseas on July 7, 1944. Shortly before that, he came down with appendicitis, and rather than submitting to surgery, he “lay packed in ice for six days,” according to the Luling Newsboy. “He felt that he would be letting his men down if he did not accompany them overseas.” The newspaper stated that he had been training with a “select group of soldiers as a combat team for a special mission.”

Aubrey’s unit, the 370th Regiment, was part of the 92nd Division. The Division carried an American bison as its emblem, because it was a segregated African American infantry division with a heritage that traced back to the “Buffalo Soldiers.” The segregated division was commanded by white officers and was the only African American infantry division to see combat in Europe in World War II. Sadly, the division was commanded by Maj. General Edward M. Almond, a poor commander who blamed the unit’s occasional poor performance on its black soldiers. The reality was that they were good troops poorly led at times. Later, Almond, one of General MacArthur’s toadies, made similar excuses for his repeated failures in Korea during 1950-1951.

Aubrey’s unit, the 370th Regiment, was part of the 92nd Division. The Division carried an American bison as its emblem, because it was a segregated African American infantry division with a heritage that traced back to the “Buffalo Soldiers.” The segregated division was commanded by white officers and was the only African American infantry division to see combat in Europe in World War II. Sadly, the division was commanded by Maj. General Edward M. Almond, a poor commander who blamed the unit’s occasional poor performance on its black soldiers. The reality was that they were good troops poorly led at times. Later, Almond, one of General MacArthur’s toadies, made similar excuses for his repeated failures in Korea during 1950-1951.

The 370th was attached as a Regimental Combat Team to the First Armored Division and arrived at Naples, Italy in August of 1944. The remainder of the division’s units arrived in Italy in September of 1944. The First Armored was a storied division that had fought across North Africa, Sicily, and at Anzio. As part of the IV Corps, it began a push north out of Rome that initially met little German resistance, as the Germans fell back to their strong defensive positions in what they called the Gothic Line.

The 1st Armored Division and the 370th crossed the Arno River north of Florence as part of a huge push against the Germans still repositioning behind the Gothic Line in the Northern Italian mountains. One of the Germans’ rearguard actions held up the Division eight miles east of Lucca. It appears that Major Biggs often was required to help green officers and men in their first taste of combat. In a poignant letter to Rosalie, Captain Phil Thayer wrote of his friend’s death on October 4, 1944:

Rosalie, after we went up into the lines, Biggs was everywhere. You knew he would be; we all knew he would be – everywhere there was trouble there would be Biggs to help straighten the situation out…. He was totally fearless of his own personal safety, after going straight into situations which were extremely dangerous. He was intent only on doing his job, whatever the case might be. We all got so we would expect him to appear if the going got tough, and surely enough, there he would be….You know, and all his friends knew that he was too good a man not to be in the thick of things when the going was tough….He was on just such a mission as I have described above when he was killed. This time a company was fighting in a town. They were not only fighting, but being heavily shelled at the same time; when up to this town in a Jeep came Biggs, to see the situation and try to help out, as usual. He paid no heed to artillery, or other dangers, merely intent on getting to the scene of the trouble, and try to straighten it. When a tire of the Jeep was blown out by a shell as he entered the town, he merely dismounted and walked up to where the fighting was going on. A shell landed near him, and he was killed instantly.

After expressing his personal grief, Captain Turner described the effect on the men of the regiment:

But Rosalie, the men and officers, who were not his close friends, acquaintances of official nature, platoon leaders, men in the ranks of every company in the regiment – when the news came down that Major Biggs had been killed – everywhere throughout the unit, the officers and men were stunned. He was respected, admired and loved throughout his unit…

The regimental commander, Colonel Sherman, also wrote Rosalie on October 28, 1944. Stating that “[w]riting this letter is the hardest thing I have ever undertaken,” the colonel described his subordinate’s death:

Aubrey was killed in action near Lucca, during some heavy shelling by the enemy. He was at the time up on the line with Captain Reedy’s Company, checking up on the situation for me. His death was instantaneous, and know he did not suffer. Major Blair was near when Aubrey was killed, and personally took him to the rear. Aubrey is buried in an Army cemetery near Vada.

The family returned to Luling for a memorial service at Luling’s First Baptist Church on Sunday, October 8th. Lt. Colonel Miller Ainsworth spoke. “Elaborate preparations” were made and Virgil Reynolds, a “nationally known musician” honored the major’s memory with a selection of music. Equally impressive was also a fly-over from one of the airbases in San Antonio.

On April 2, 1945, in a ceremony at Aloe Field, near Victoria, attended by Rosalie and his parents, Major Biggs was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for his actions days prior to his death. A platoon encountered heavy machine gun and mortar fire on its first combat mission. Going forward, he found the unit in total disarray and took over command.

“He completed a rapid but efficient reorganization and by his vigor and enthusiasm rallied the whole platoon and got it ready to move. Major Biggs then personally led the platoon toward the enemy to the north in the face of concentrated fire by enemy machine guns, mortar and small arms. He continued to lead the platoon until it had driven the enemy off the south bank of the [censored]. Major Biggs’ courage, determination and indomitable leadership inspired the platoon to reach its objective and his heroic performance reflects the highest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United States.”

In 1948, President Harry Truman ordered the complete desegregation of the military. African American troops had served in the military in all of America’s wars. It was long overdue. Aubrey’s loyalty to his troops and the leadership he showed no doubt helped pave the way for this milestone.

Major Biggs’ Headstone – McNeil Cemetery