JASON KENNETH LAFLEUR

HE WAS WILLING

by Todd Blomerth

“He was larger than life. He had this big smile, and loved to laugh. He always had my back.” E-5 (Ret.) Albert Fambrough

I want you to try to imagine the following:

You are the parent of two adult children. The oldest is in the military, and is stationed in Iraq. The doorbell rings. You are trying to get out the door with a friend, to see a Seattle Mariners – Boston Red Sox baseball game. You assume the bell has been rung by the neighbor kid, who likes to come over and play with your dog. You peek out the front door expecting to see a small child. Your eyes fall instead on two sets of military shoes and uniform trousers. Without opening the door, you know why the men wearing them are here – your only son has been killed in action.

That is what happened to Kei LaFleur in 2007. She, along with her ex-husband Chuck, and her daughter Megan, were confronted with the worst news of their lives. A beloved family member, vibrant and full of life, had been killed in a faraway land, serving his country in the United States Army.

That family member was Jason LaFleur. This is his story.

Jason Kenneth LaFleur was born on January 28, 1979 to Chuck and Kei (Warden) LaFleur. His sister Megan came along two years later. The family lived in Houston at the time, where Chuck and Kei both worked for Southwestern Bell. They transferred to the Austin area in 1985, and settled in Lockhart. The LaFleur children attended Lockhart schools. Jason’s parents instilled in them the joy of travel, and the family often took vacations to Colorado and New Mexico.

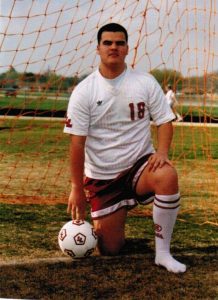

Jason played soccer all through school, and was a drummer in the Lockhart High School Band. A good student, he took many college level courses. He graduated in 1997.

Jason’s folks divorced shortly after he graduated from high school. Kei moved with her job to Washington State. Chuck  moved to Durango, Colorado.

moved to Durango, Colorado.

Jason received a partial scholarship to the University of Mississippi. Two years at Ole Miss, in Oxford, Mississippi, resulted in a lot of fun, but perhaps was not the route Jason wished to take. More mature, but still uncertain of what to do, Jason returned to his beloved Texas, taking some courses at Texas State University.

He then moved to Durango, Colorado to be closer to his dad. He worked at Home Depot, at the city Recycling Plant, and with his dad’s contracting business. He kept up with all the European soccer leagues, and coached kids under twelve in the Durango Youth Soccer program. He relished Colorado winters, when he could snow ski, an activity he loved almost as much as soccer.

Jason was an ardent patriot. In the words of a woman whose Durango house he boarded at, “He was just very adamant about supporting the president and defending our country.” Somewhere in this time of maturing and introspection, he decided to enlist in the Army. Jason was a big man physically, but he was overweight. He began to eat better and spend time in the gym. His mom knew he was serious about enlisting when he began running every day, an exercise he detested.

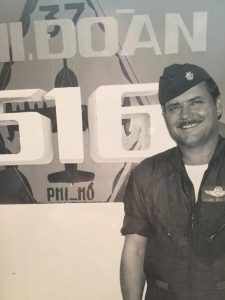

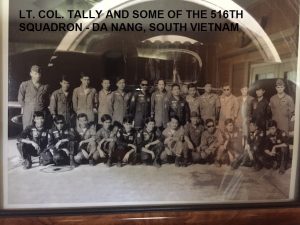

In retrospect, Kei believes her son met and visited with a retired helicopter pilot, who whetted his appetite for the Army in general, and Army aviation in particular. Although he rarely discussed it, Jason told someone, “I’ve just got to get through this first enlistment, and then I can go into aviation.” After he died some of his notebooks were found showing he had been studying for Army aviation tests between missions.

Jason enlisted in the Army in 2005. With his test scores and background, he could have chosen any number of military specialties. He chose to be an infantryman. In today’s Army, enlistees going into combat arms (artillery, armor and infantry) do both basic training and advanced combat training at one location – in his case it was Ft. Knox, Kentucky. There, he became fast friends with several other enlistees. At 25 years of age, he was an “old man” compared to other young soldiers.

About half way through this initial training, called One Station Unit Training, someone showed up from Ft. Bragg, looking for volunteers for Airborne School. Those who volunteered, and who completed the arduous three week course, were promised assignments with an Airborne Cavalry unit being formed at Ft. Richardson, Alaska.

About thirty of the young men volunteered. Some were just gung ho. Others went to jump school for more prosaic reasons. Some of the volunteers did it because they didn’t want the military occupation specialty of Eleven Bravo – infantryman- “so they wouldn’t have to ride in a Bradley Fighting Vehicle,” seen as a bigger target than the vehicles used by cavalry scouts.

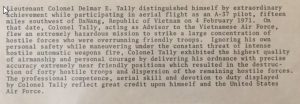

Jason completed the intense three weeks at Ft. Benning, Georgia and proudly wore jump wings on his uniform. He was assigned to Bravo Troop, First Squadron (Airborne), 40th Cavalry Regiment. He joined his unit in November of 2005. His military specialty had a certain cache to it – cavalry scout, or “19 Delta.”

The 1/40th Cav (Abn) training in Alaska was arduous. Part of the 25th Infantry Division’s Fourth Brigade, It was to be a rapid deployment unit for Southwestern Asia. Ultimately, the unit would fight in Iraq and Afghanistan. Jason enjoyed the challenges. He thrived on the structure and discipline. And, he loved the camaraderie. He made fast friends with and won the admiration of many of the young men he served with.

Albert Fambrough, a slow talking Kentuckian, went through Basic training with Jason. In Alaska, he and his wife were expecting their first child. Jason and others often came to the Fambrough apartment for meals. Jason’s “big Texas grin” is etched in his memory. Albert and his wife thought so much of Jason that they planned to name him as one of their unborn child’s godfathers.

Inevitably, the 1/40th received orders to Iraq.

After the capture of Saddam Hussein, the United States forces were slowly withdrawn from Iraq. However, all attempts at establishing a working government quickly foundered. Al Qaeda terrorists moved into the power vacuum, disrupting any chance of peaceful resolution of political issues. Mutual hatred and distrust between Sunni and Shiite Muslims, and the growth of sectarian militias, compounded a witches’ brew of long simmering problems.

In 2006, President George Bush began meeting with military and civilian leaders, trying to come up with a plan to stabilize the country. “The New Way Forward”, better known as “the Surge,” came into being. 20,000 additional troops were sent to Iraq, and the aims of the military were refocused “to help Iraqis clear and secure neighborhoods, to help them protect the local population, and to help ensure that the Iraqi forces left behind are capable of providing the security.”

It was highly controversial at the time. While by no means unanimous, most observers, including critics such as Hilary Clinton and Barack Obama, would ultimately agree that the Surge was successful.

As part of the Surge, in October 2006, the 1/40th Cav was flown into Baghdad, and then moved south to Forward Operating Base (FOB) Falcon near Checkpoint 20, the last site under U.S. control.

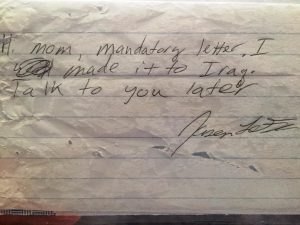

When they arrived at FOB Falcon, the troop’s first sergeant ordered all the young troopers to write a letter home their moms. Jason, six years older than most of the soldiers, thought this order was silly, but in typical droll fashion, did what he was told to do.

Jason’s first letter home to his mom, ‘complying’ with the top sergeant’s orders

The unit’s operational area consisted of around forty square miles west of the Tigris River, just south of Baghdad. Crisscrossed by irrigation canals, with fish farms, palm trees, tall grass, and narrow roads, its small villages were hotbeds of El Qaeda activity.

One such village was Hawr Rajab. Under the control of Al Qaeda and that group’s mostly foreign jihadis, it was on a major infiltration route into Baghdad for suicide bombers. Al Qaeda was armed with AK47s, machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, and a “seemingly endless supply of homemade improvised explosive devices [IEDs],” many made with urea fertilizer and nitric acid.

American patrols and sweeps always resulted in ‘contacts’ – a euphemistic term for combat, in the squadron’s area of operation.

The 1/40th’s first six months in-country saw an increase in Al Qaeda activity in their area of operation, as adjoining American forces displaced Al Qaeda jihadis into the Hawr Rajab area.

Jason during a break on a recon in Iraq

Eight months into his tour, Jason received leave. He flew into Seattle, surprising his mother and sister. Equally important, Chuck happened to be in the area. Quick arrangements were made, and Jason and his father reunited for Father’s Day. It was a joyous time. It would be the last time his family would see him.

Because of growing American impatience, and the Surge, many Sunnis, originally hostile to the United States, began to rethink their positions. Tribal sheiks, or chieftains, realized that by enlisting the U.S. help, they could rid their villages of Al Qaeda fighters, who were terrorizing the local populaces. Additionally, many sheiks concluded that the U.S. could provide the Sunni Muslims with protection against the predatory practices of the largely Shiite Iraqi government forces, and various hostile militias.

After seeing the success the Americans had had in other areas in providing support and security, Sheik Ali Majid al-Dulaimi, a sheik at Hawr Rajab, of the Dulaimi tribe, cautiously approached the American Army about ridding his village of Al Qaeda. Sheik Ali was no stranger to Al Qaeda’s violence. Imbedded with the 1/40th, New York Times reporter Martin Gordon noted: “Al Qaeda militants had killed his father, kidnapped his cousin, burned his home to the ground and alienated many of his fellow tribesmen by imposing a draconian version of Islamic law that proscribed smoking and required women to shroud themselves in veils.” Quietly, Sheik Ali began recruiting locals into a small self-protection group, and reached out to the

The village of Hawr Rajab, marked with red marker

Americans. Sheik Mahir Sarhan Morab al-Muini, of another tribe in Hawr Rajab, also came forward asking for help.

Most of the ‘big picture’ was not available to the trooper on the ground. Daily life was filled of staying alive, and completing the assignment ordered. FOB Falcon had ancillary fortifications in the squadron’s Area of Operations. Bravo Troop rotated platoons in and out of Patrol Base Dog. In May of 2007, a suicide bomber driving a dump truck rammed the Patrol Base. Men were lost and injured. Iraqi summers are vicious. The men rebuilt the PB in the blazing heat, and continued to patrol and scout.

With the limited number of soldiers available in the 1/40th’s area of operation, it was critical that the Americans obtain the locals’ full support. Information given the Americans resulted in a successful air strike on an ice factory where Al Qaeda fighters were hidden. A decision was made to move 1/40th’s A Troop into Hawr Rajab, to distribute food, and to help the sheiks re-assert their authority over the 8000 villagers.

In late July 2007, an abortive attempt was made to support Ali’s men attacking Al Qaeda strong points in Hawr Rajab. Blowing sands grounded supporting American gunships. Al Qaeda, tipped off to the movement, attack Sheik Ali’s force, forcing a retreat, and nearly killing a subordinate’s sister and her children. In the following days, 1/40th made several raids against the enemy, trying to keep it off balance, while other plans were made.

On August 4, 2007, another attempt was made, this time with A Troop leading the way. The American soldiers wore Kevlar helmets, body armor, Nomex gloves, and ballistic glasses. Engineers with anti-mine vehicles moved out at five a.m., followed by soldiers who were to enter the center of the village, distribute food, and allow psychological operations to begin. The dual objective was a show of force and support for the local Iraqis, as well as an effort to win the ‘hearts and minds’ of potential allies.

There was one road in and out of Hawr Rajab from the north, simplifying Al Qaeda’s task of IED placement. Soon, an American vehicle hit an IED, blowing the cab over 50 feet and injuring the driver. As other troopers pushed into the village, they were aware of closed shutters. The locals knew something bad was up.

Elements of A Troop reached the village center. Humvees formed a protective circle, as announcements went out over loud speakers for the villagers to come get food. And then, the radio came alive. The 1/40th’s commander, Lt. Colonel Mark Odom and his humvee had hit an IED. All four of the vehicle’s occupants were badly hurt.

Jason, with Bravo Troop, was part of the squadron’s Quick Response Force. Sergeant James Allred was a section sergeant for Bravo Troop. “We weren’t in our Area of Operation. We were there to support Alpha. We were to pick up some detainees, and return to the FOB,” he told me. “Route clearance vehicles were to the front. We assumed IEDs had been cleared. Suddenly, the colonel’s humvee got hit.”

With admiration for Lt. Col. Odom’s leadership despite his extensive injuries, Allred explained that “our mission had suddenly changed.” He and Medic Dustin Wakeman assisted in extracting the injured men from Odom’s Humvee. Sergeant Donnie Cartwright also dismounted from the humvee where Jason was gunner. Bravo’s men and vehicle assumed defensive positions around the perimeter. Things calmed down – although in the madness of the event this is a relative term. It was time for Bravo’s men to return to FOB Falcon. “I radioed Jaron [Holliday} to back up and pick us up. The last thing he said was ‘roger.’”

The humvee hit a pressure plate, or a massive IED was activated remotely by phone. “Wakeman had gone back to the humvee to take a breather,” recalls Allred. “Sergeant Cartwright and I were standing there when the whole thing went up in pieces. We were pretty close.”

Cartwright asked, “Where is the humvee?”

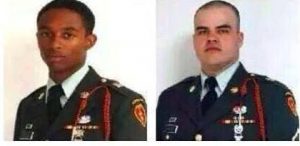

The humvee was gone, and with it, three young men. Sgt. Dustin Wakeman, Corporal Jaron Holliday, and Corporal Jason LaFleur were killed instantly.

New York Times reporter Michael Gordon witnessed the mayhem from another perspective:

We drove back toward Checkpoint 20 and came upon a terrible sight. The twisted wreck of a Humvee was in the middle of the road. Combat medics were hovering over two soldiers lying in the grass. One was the turret gunner. The other was Odom, whose face was swathed in bandages. The wounded soldiers were lifted by stretcher into waiting Humvees and driven back.

Another Humvee, meanwhile, drove down from Checkpoint 20 to guard our flank. Suddenly there was a massive blast. Much of that Humvee disintegrated into fragments that rained down around us. Nobody could survive such a blast. The radio traffic reported three killed in action.

Again, in the words of reporter Michael Gordon:

When we got back to Checkpoint 20, the outpost was silent. The soldiers had lost three of their comrades. Another eight had been wounded. The enemy had suffered no casualties. Food had been given out to 40 residents.

At Forward Operating Base Falcon, the commanders imposed “River City” — they shut down the unclassified Internet connection the soldiers used to chat with their families and to blog so that word of the casualties would not spread until the next of kin were notified. That night, I went to the airfield at the base for the “angel flight.” A formation of soldiers lined up and saluted as the caskets of the three dead soldiers were carried to the tarmac so they could be flown away.

Ordinarily, Cpl. Farmbrough was the squadron commander’s driver. On August 4, he had been assigned to man the radios in the Tactical Control Center, back at the Forward Operating Base. “When I heard what had happened, I knew who had died. I started crying over the radio.”

In reading Michael Gordon’s account, and listening to James Allred’s version, it is in some respects like two different occurrences. The reality? The compression and expansion of perceived time, the incredible stress of combat, and the events seen through different lenses, focused on different issues.

“Jason was bold,” Allred remembers, but occasionally maddeningly hard-headed. “We butted heads sometimes. He was older  than me. I had joined the Army at eighteen, and was a very young NCO.” Allred had been a drill instructor, and admired the big Texan. “He was the soldier I had that made me want to do my job better.” Sergeant Allred states, “We were all a brotherhood there. I am still dealing with it.” Allred spoke on behalf of Jason at the men’s’ eulogies at FOB Falcon. “I was able to personally say goodbye,” as Jason’s casket was loaded to be flown home.

than me. I had joined the Army at eighteen, and was a very young NCO.” Allred had been a drill instructor, and admired the big Texan. “He was the soldier I had that made me want to do my job better.” Sergeant Allred states, “We were all a brotherhood there. I am still dealing with it.” Allred spoke on behalf of Jason at the men’s’ eulogies at FOB Falcon. “I was able to personally say goodbye,” as Jason’s casket was loaded to be flown home.

Corporal Jason LaFleur’s body came home to Texas. His funeral was held at Lockhart’s Eeds Funeral Home. Jason hadn’t lived in Caldwell County in nearly ten years. The LaFleur family was stunned by the outpouring of love and concern shown by the large numbers of Caldwell County folks in attendance. Jason is buried as Ft. Sam Houston National Cemetery.

The loss of this young soldier continues to ripple through his family, and his many friends. When speaking to me, Albert Fambrough could not hold back his tears. To this day, and despite logic and reason, James Allred remains haunted by what happened. I have “what iffed’ the situation every day.” If they hadn’t back up a few feet. If he hadn’t radioed Holliday to come pick them up so they could return to FOB Falcon. If, if, if….

Megan, Jason’s sister, succinctly describes the devastation when she says, “I felt like I lost my whole family.” Her mother Kei understandably became “all consumed” with the loss of her only son. Her father Chuck could not deal with the loss. He withdrew, as if to protect himself emotionally. His son’s death has exacerbated health issues.

Megan’s sense of loss is nuanced. She and Jason weren’t close growing up, but that had begun to change. The ability of siblings to reach a new or renewed level of affection and understanding with age and maturity has been taken from her and her brother. “I regret the inability to get together,” she says. “This made me feel how fragmented our family had become. I feel very small.”

Kei visits her son’s grave at least once a month. She is a member of American Gold Star Mothers. Comprised of moms who have lost sons or daughters in the service of their country, the Gold Star Mothers volunteer to support veterans and those serving in the military. Gold Star Mothers offer support and friendship, but also makes the most of the members’ situations to help others even less fortunate. She is also a member of the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors, a grief and healing organization. She has mentored through that program, “talking to other moms who may not be as far down the road as I am.”

As I was writing this story, I received this message from Kei LaFleur: “When [Jason] told me he was going to enlist, I felt I needed to counsel him. Not to dissuade him, but to have him think about other military options. I told him in the Army, he would be sent to the desert. Probably pretty quick. He’s big and he’s strong. And he said to me, ‘I know Mom, but I am willing.’ So if people remember anything about Jason, they should remember that he was willing.”

The three troopers killed – Holliday, LaFleur, and Wakeman

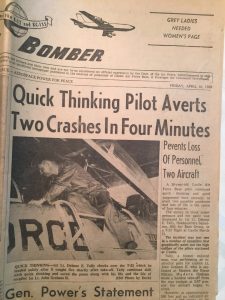

Aftermath of several IED attacks witnessed by 1/40th troopers while in Iraq

Kei at her son’s grave Ft. Sam Houston National Cemetery

The window of a Gold Star mom

Note: I am indebted to Kei LaFleur for her time and kindness in providing pictures and stories of her son. She also helped me make contact with Megan LaFleur, James Allred, and Albert Fambrough who honored me with their time and recollections.

New York Times journalist Michael Gordon was embedded with the 1/40th. His story appeared on September 2, 2007 and can be found at http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/02/world/africa/02iht-02checkpoint.7348866.html

The Durango (Colorado) Herald front page story of August 9, 2007, entitled Soldier LaFleur Proud to Serve was provided to me by Kei LaFleur.