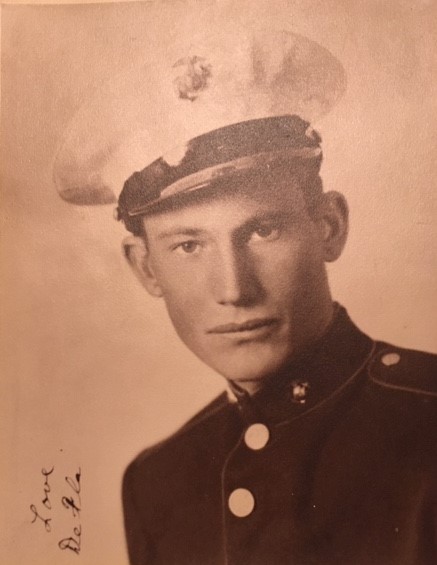

A PROUD MARINE TANKER AND VETERAN

1922 – 2005

By TODD A. BLOMERTH

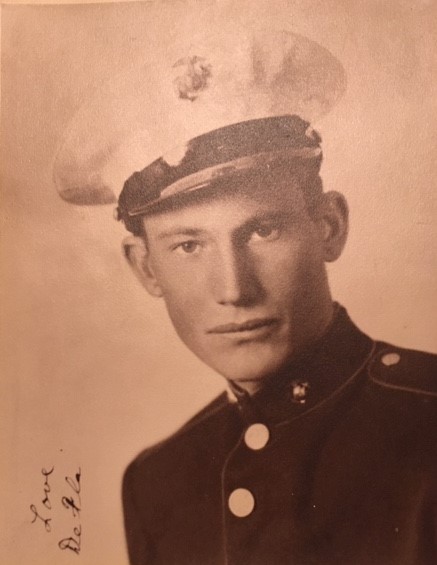

I moved to Lockhart in late 1981. Soon I started hearing about a fellow named Spike Strawn. He and his son Fla owned S&S Fertilizer with an office in a small building on Highway 183 about where the McDonald’s is now. S&S also had a crop-dusting service. Word was that you didn’t want to get crosswise with Spike, as he was someone who didn’t put up with a lot of guff or suffer fools lightly. He was a proud United States Marine who’d fought for our country during World War II, and his training, background, and combat experience made him a fearsome adversary.

When I finally met Spike, I concluded that everything I’d heard was true. Rawboned, tough as shoe leather, and plain spoken to be sure. But there was another side to Spike Strawn. He wasn’t some caricature. He was complex, highly intelligent, often thoughtful man. Sure, he’d let you know when he thought your thinking wasn’t on course. But he was a loving father and grandfather, a raconteur, and, if he decided you were okay, your best friend.

In short, Spike was a living, breathing example of someone whose family had survived the Great Depression, who went through four major island landings in the Pacific against America’s most ferocious and merciless foe, and who’d proved to himself and others that he had what it took. Spike had grit.

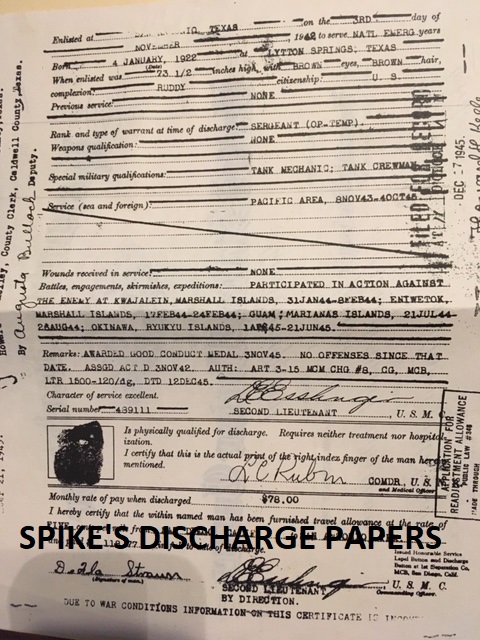

Cecil DeFla “Spike” Strawn was born on 4 January 1922 in Lytton Springs, Texas, the third of eight children of Littleton Lawson “Dill” Strawn and Beatrice Lillie (Ward) Strawn. Besides farming, Dill did whatever it took to put food on the family’s table. Dill was a gifted mechanic and could fabricate parts for just about anything. When he wasn’t farming, he worked for various oil companies in the area. Dill also played semi-pro baseball for company teams. Beatrice took care of the growing family. She gardened, canned, cooked, and ensured that Jenella, Helen Louise, Spike, Doyle Ray, Marjorie, Juanita, Herschel and Pat were clothed and clean. The 20s and 30s were lean times, and everyone in the family was expected to contribute to keeping food on the family table.

Schooling started in Lytton Springs. The place had become an oil boom town in the mid-1920s. At that time, it boasted four grocery stores, a confectionary, a barbershop, and Masonic Lodge, as well as several churches. Life was precarious. Spike would often walk to school, sometimes barefoot, even in the winter. In the second grade, he contracted pneumonia and stayed in bed for almost two months. There were no antibiotics. As he recalled in 1995, “they rubbed you with liniment and hoped for the best.” He survived, but a chest x-ray taken when he enlisted in the Marines showed his right lung stopped growing as a result of the disease. It never slowed him down. In the sixth grade, his class had to submit to a series of twenty-one shots because of a rabid dog, which Dill eventually shot.

In high school, Spike played six-man football and basketball. The oil boom was dead by this time, and Lytton Springs suffered mightily. He landed a job earning seven and a half cents an hour picking and sorting tomatoes. A long day would net him 60 to 80 cents, which was substantially more than many grown men were making. Later, he pulled corn and picked cotton. At one point, he earned 40 cents cutting and shucking corn for his uncle. At the end of the week, he’d have $2.50 – a princely sum.

Entertainment was simple. Square dances (without instruments, and only with singing), or catching a ride into Lockhart to see a movie. His best friend was his cousin, Frank Coopwood, Jr. The price of an evening in the county seat: 15 cents for the show, 10 cents for a hamburger, and 5 cents for a Coke.

War news had become commonplace in the late 1930s. Hitler’s Germany had bluffed France and England and recovered Sudetenland, stolen Czechoslovakia, and absorbed Austria. Franco’s Nationalists, with the aid of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy was quickly putting finished to Republican Spain. China was under the boot heel of the Japanese military, which had killed over 200,000 civilians in what was rightfully called “the Rape of Nanking.”

Most Americans were adamant that their country shouldn’t involve itself in another world conflict. Over intense opposition, the first peacetime draft was enacted in mid-1940. Then in late 1940, the National Guard was nationalized for one year. The country slowly awoke to the reality that “the Arsenal of Democracy” needed to do much more than talk about helping its oldest ally, Britain. Any doubts as to the extent of the conflagration were put to rest when Germany turned on a fellow aggressor and attacked the Soviet Union in June of 1941.

Meanwhile, the United States imposed an embargo on steel and oil heading toward Japan. It was the last straw to the militarists controlling the Empire’s government. Already badly and surprising beaten when the Japanese Army made a move against the Soviets in Siberia and Mongolia, it turned its interests south, toward British and Dutch colonies… and the American Philippine Commonwealth.

Then came the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. America was “all in.” Less than a year later, on 3 November 1942, Cecil DeFla Strawn enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. After a night in San Antonio’s Crockett Hotel, he and 98 other men from the area were loaded on a train for San Diego, California. Three long days later, they marched two miles to Camp Pendleton, had their heads shaved, and met the drill instructor. The DI quickly assured them that the training base’s colonel was “Big Jesus,” that the DI was “Little Jesus,” and that **** flowed downhill. Weeks of boot camp ensued, and then more training on the rifle range.

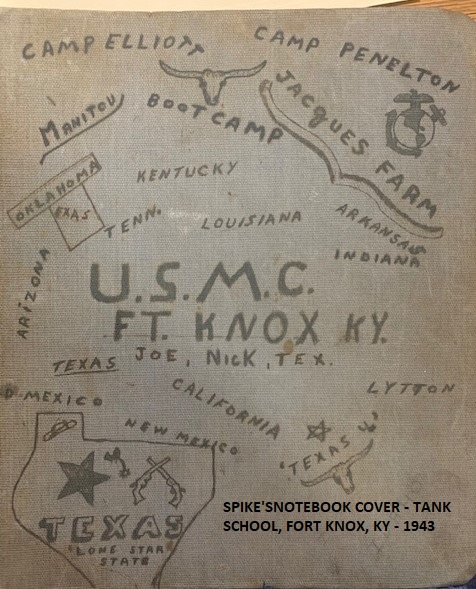

Spike asked to become a tanker, and surprisingly, the Marines agreed. Because the USMC didn’t have its own armored school, he spent several months at the Army’s Armored School at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Dill Strawn, determined to see his son, rode a packed train from Texas, standing up the entire way, and spent four days at Fort Knox, sleeping surreptitiously in the barracks with the Marine trainees.

As soon as he returned to California, Spike and his fellow tankers were shipped to Hawaii and became part of a replacement detail. On the Big Island, he and three others were assigned to the 22nd Marine Regiment. He was about to enter the war. The 22nd Marines and its men soon learned they were to be part of a landing force in the Marshall Islands. Spike’s life would never be the same.

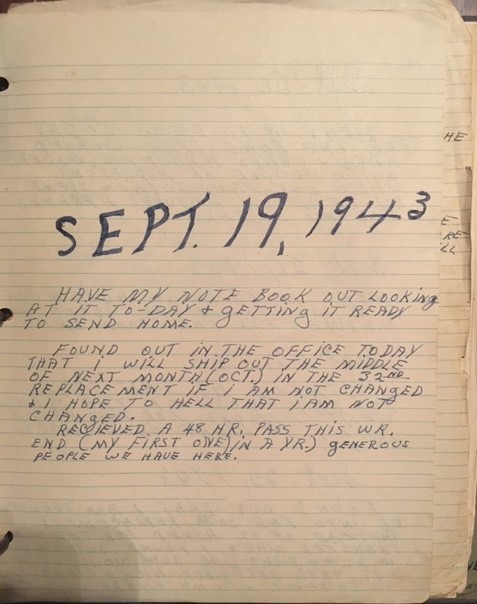

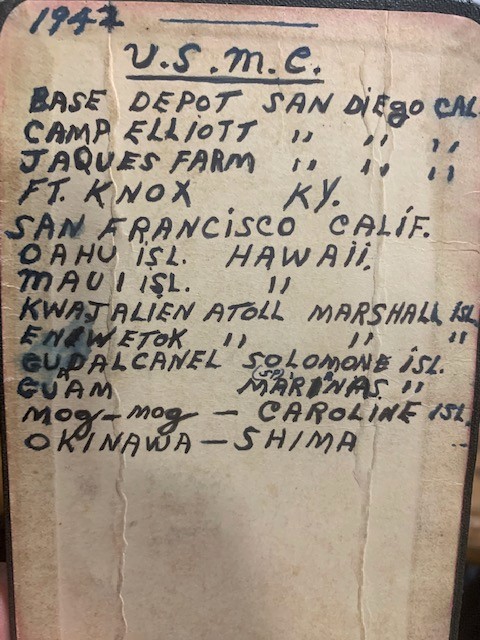

On 16 January 1944, Spike and the 2nd Separate Tank Company of the 22nd Marine Regiment boarded the USS President Monroe. After a brief stop at Pearl Harbor (after training on Maui and the Big Island) Spike noted in his pocket notebook that on 23 January he “left Pearl Harbor for the Marshall Islands.” Ten days later, Spike “witnessed my first air and naval bombardment in Marshall Islands.”

The 22nd Marines was part of a large American force attacking the Japanese occupied Marshall Islands in the advance toward the Japanese home islands. Initially held in reserve during the landing on Kwajalein, the 22nd struck Engebi, and after fierce fighting, secured the island. Spike’s notes of 19 February 1944 state: “Landed on next island [Eniwetok] after Army 106th Regiment failed. Much more opposition than expected. So far in all operations 2nd Sep[arate] Tank Co. has lost three tanks and 7 or 8 men.” Over 800 Japanese were killed on Eniwetok.

The baptism under fire continued. The island fighting was extremely vicious. The Japanese rarely surrendered. After three days and nights without rest, what Spike describes as “the last island” in Eniwetok Atoll [probably Parry Island] was attacked. The Americans did a better job of softening up Parry than had been done on Eniwetok. After two days, only 105 Japanese of the 1100 defenders survived to be captured. Spike’s tank company lost ten more men killed.

Finally, Spike’s company was put ashore on a small deserted island in the Kwajalein Atoll chain supposedly for “garrison duty” – and immediately forgotten. With little food, the men resorted to stunning fish with hand grenades. Three weeks later, someone finally remembered the bedraggled bunch and pulled them off the island.

Spike’s mail caught up with him. He discovered that his cousin and best friend, Frank Coopwood, Jr. had been killed in the mountains of central Italy on 23 December 1943 while fighting with the 36th “Texas” Division.

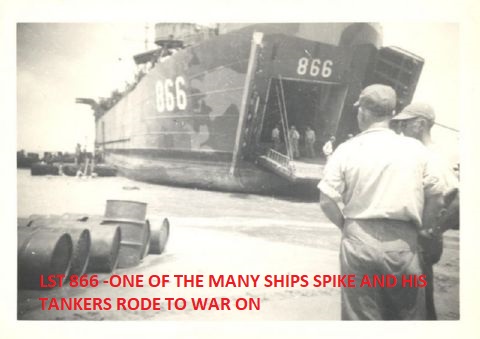

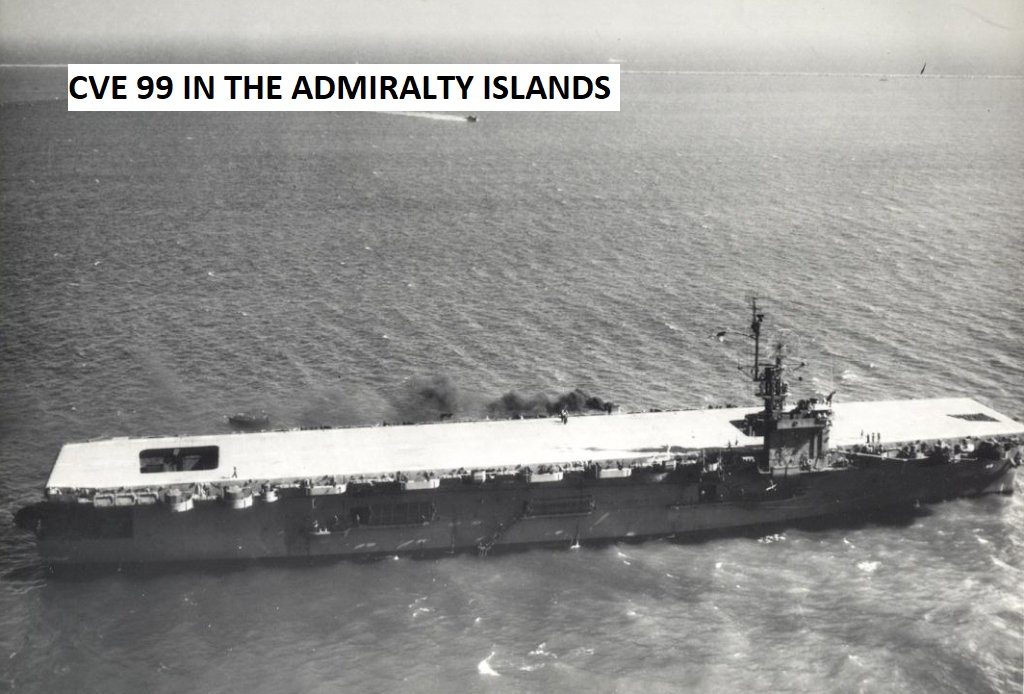

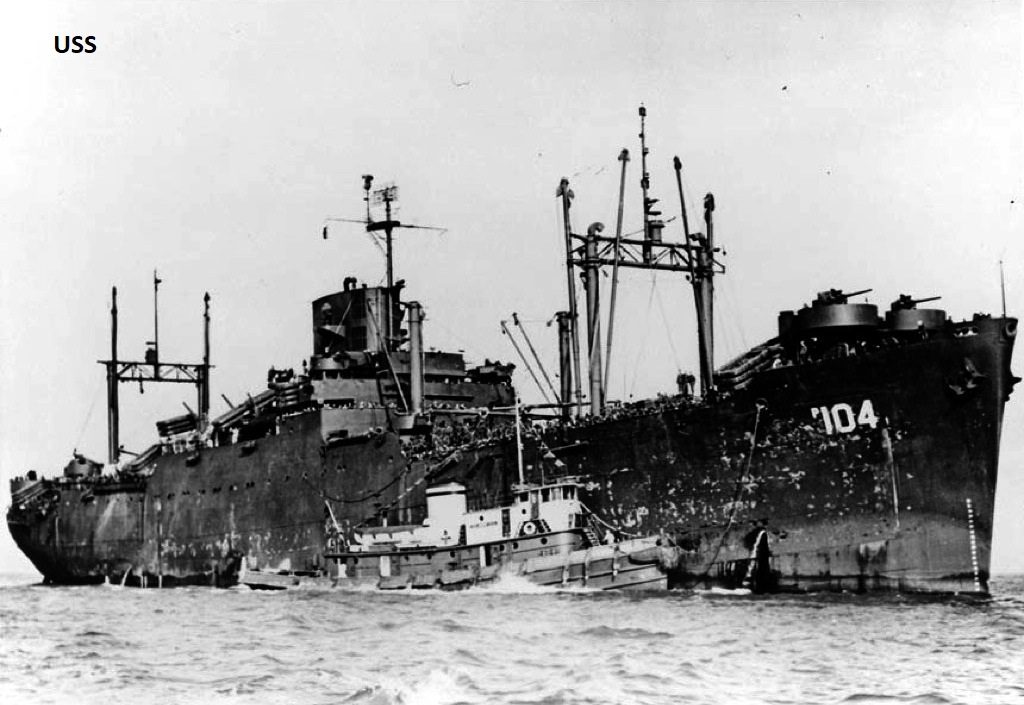

USS Comet AP-166, USS West Point AP-23, LST866, CVE 99 USS Admiralty Islands – some of the ships Spike traveled on in the Pacific

In 1995, Spike recorded some recollections of his time in the Marines. One incident of the Marshall Islands stood out. One of the 22nd’s mortar platoons had an undersized and very young Marine. The kid was deeply loved and treated as if he was the platoon’s mascot. During some point in the fighting, Spike recalls the platoon coming off the line, and everyone in it was “bawling like a baby.” The young marine had been killed by a Japanese flamethrower.

After Kwajalein and Eniwetok, the 22nd Marines was shipped to Guadalcanal. for refitting and training for the next landing. Many of the 22nd’s marines had trained in 1942-1943 in American Samoa. Over a thousand men were discovered to be infected with filariasis, a nasty tropical roundworm. Most had to be evacuated.

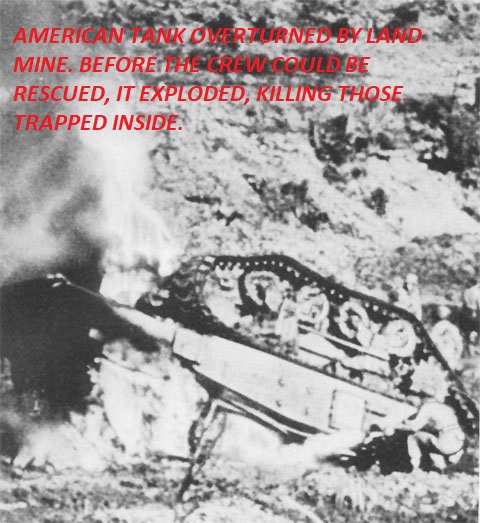

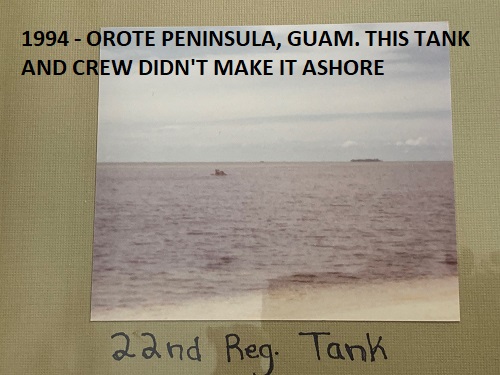

Not all deaths were combat related. Spike vividly recalled the death of a tanker. During one operation, the Navy “got scared” and let off the marine tanks from its landing craft in “about 80 feet of water.” A marine named Drumgould was in the gunner’s seat when the thirty-three-ton Sherman drove off the ramp and immediately sank. Somehow, Drumgould pushed through an eight-inch opening, and made it to the water’s surface. His ears, nose and mouth bled from the pressure change. The tank driver was trapped when the Sherman settled, blocking his way out. He died, and Spike recalled Dromgould, haunted by the event, “walking, walking all night long.”

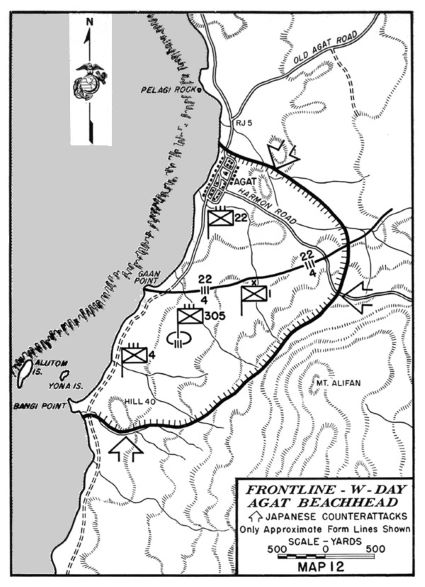

The regiment’s strength was rebuilt, and along with the 4th Marines and an Army regiment, formed into the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade. The newly rebuilt regiment trained intensely. The next stop – the island of Guam.

On 22 July 1944, the Americans began the attack to retake Guam, lost to the Japanese shortly after Pearl Harbor. Guam and nearby Saipan and Tinian could hold airfields within range of the Japanese home islands for the new B-29 bombers. The 1st Provisional Brigade landing was met by ferocious resistance. A beachhead was secured, and then the marines withstood repeated attempts to push them back into the sea. As the tanks landed, Spike spied seven dead marines lying behind a coconut log. All had been killed by a sniper. Spike’s platoon leader, a young lieutenant from Cuero, had predicted he wouldn’t survive. He was right. Within days of the landing, the young officer was killed.

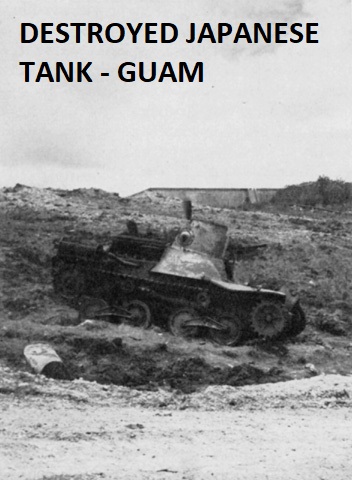

Japanese light tanks were no match for the American’s Shermans. But the Americans’ armor took many losses from suicidal attacks with satchel charges. At night, Spike and other tankers withdrew into the marines’ defensive lines to avoid the enemy’s intense shelling, and sneak attacks.

The island was officially declared “secured” on August 10. By that time, over 11,000 Japanese had been killed. Several thousand fled into the mountainous terrain. . As the mopping up continued, his tank company was tasked with guarding a hospital on the north end of the island. Security was relaxed – there seemed little risk. A young private in the company named Parsons joined a volleyball game nearby – and was shot dead by a sniper. Parsons was one of at least fifteen in the company killed.

The 22nd Marines shipped back to Guadalcanal to refit. Everyone anticipated that the closer to Japan the landings became, the more ferocious the resistance would become. While on Guadalcanal, the 22nd Marines became part of the newly formed 6th Marine Division. Spike’s tank company was designated B Company, 6th Tank Battalion, 22nd Marines.

The next landing – Okinawa. Sixty-six miles long and seven miles wide, it was the largest of the Ryukyu Islands and was considered one of Japan’s home islands. Seven American divisions – four Army and three Marine – landed on 1 April 1945 in the largest amphibious landing of the Pacific War. Nearly 200,000 soldiers and marines,supported by the US Navy’s hundreds of warships, splashed ashore and found virtually no resistance.

Where was the enemy? Soon, the Americans found out.

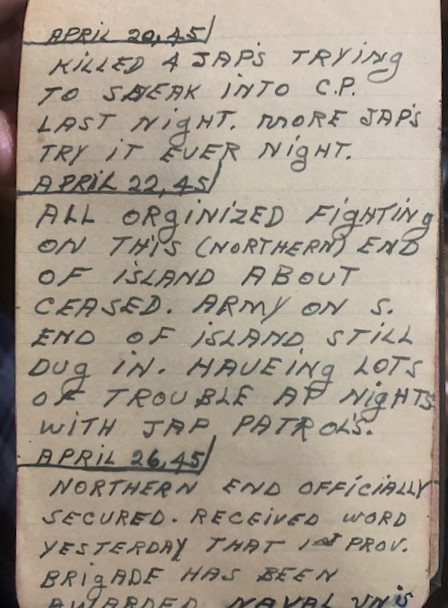

Okinawa was soon split in two. The Sixth Marine Division swung north. Resistance grew worse as the division advanced. Soon, the remaining Japanese were isolated and destroyed. As noted in Spike’s notes the northern portion of the island was secured by April 22.

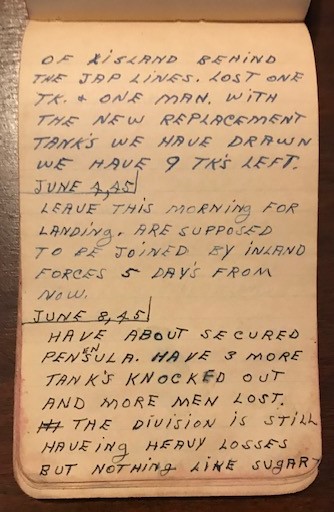

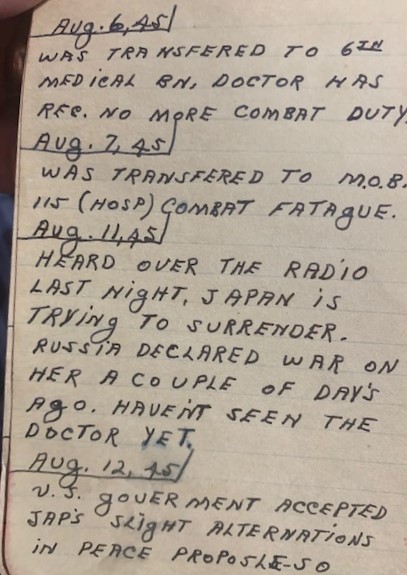

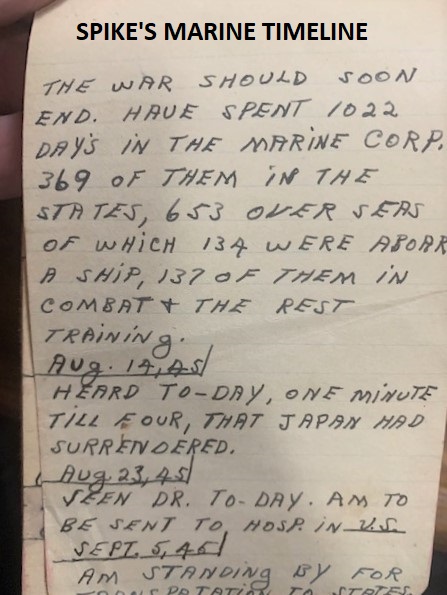

A page of Spike’s notes of the fighting in northern Okinawa

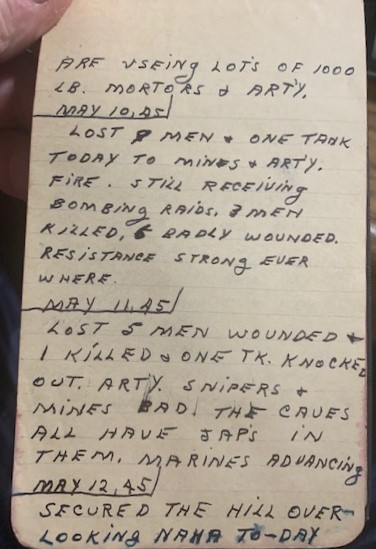

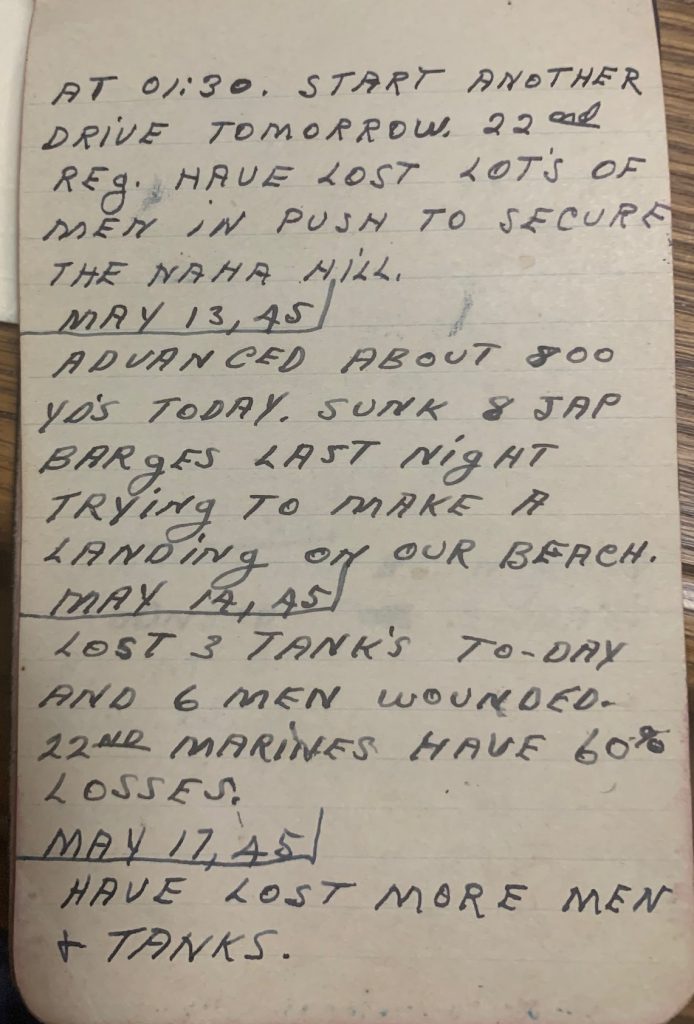

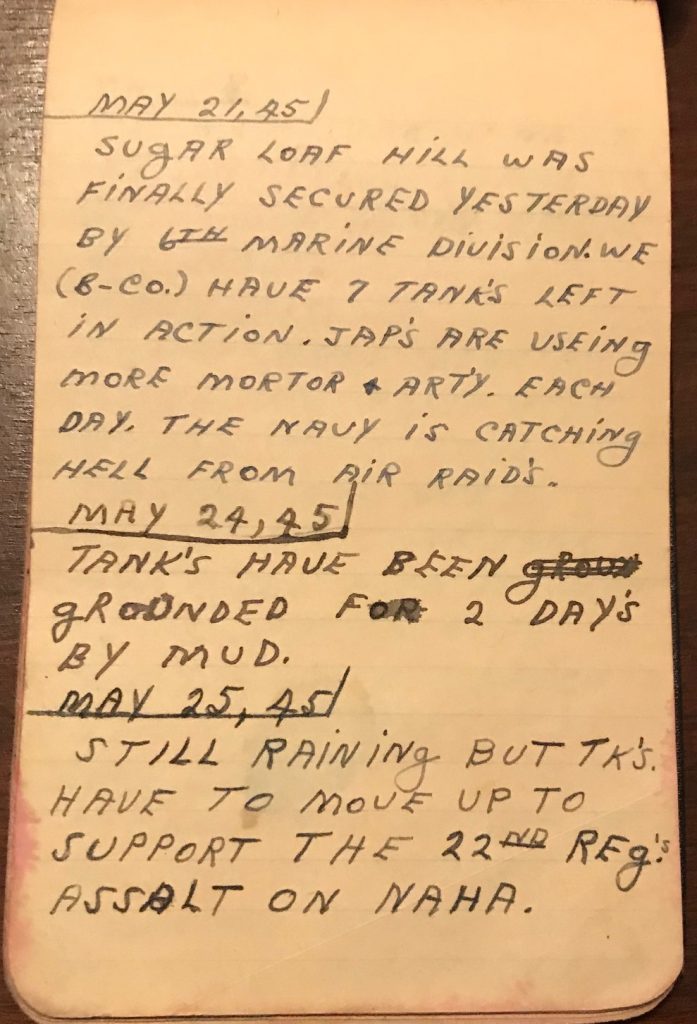

The Sixth Marine Division was ordered south. There, over 100,000 Japanese soldiers, marines, naval personnel, along with conscripted Okinawan labor units had turned the island’s southern mountains into an almost impenetrable fortress. The Americans’ naval and air superiority seemed to have little effect against an enemy using an enormous array of tunnels, caves and ingenious defenses commanded by the brilliant General Mitsuru Ushijima. Spike’s notebook entries rarely contain personal reflections. However, the futility of the battle becomes vivid in entry after entry of tanks destroyed, men killed, horrible weather, and combat exhaustion.

One can’t read these shorthand versions of hell, without being moved. Spike speaks of fifty days of rain, of mosquitoes, of casualty figures that beggar the imagination.

Shuri Castle, the Gorge, Tombstone Ridge, Dead Horse Gulch, Naha, Kakazu Ridge, the Pinnacle, Wana Draw. These became names synonymous with misery and death. Rains began, and the front lines began to appear like something out of World War I trench warfare.

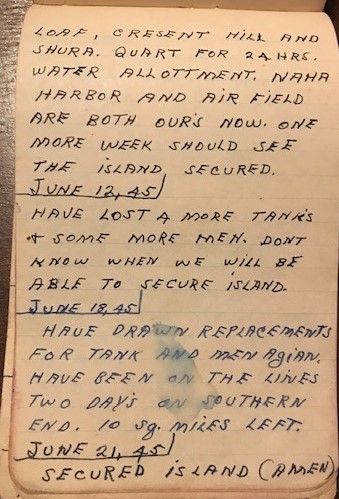

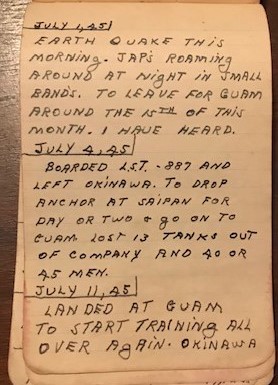

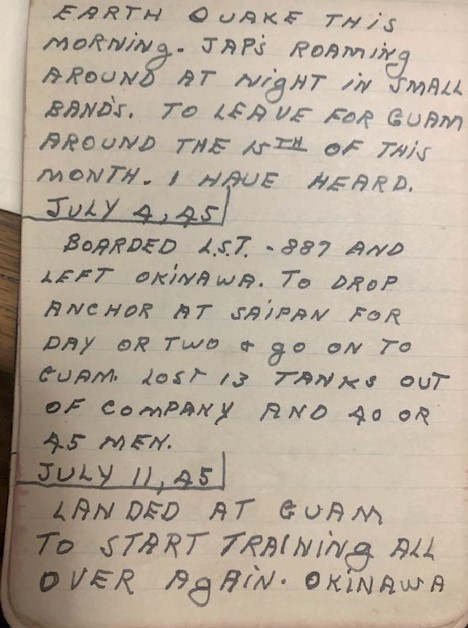

Some of the journal entries during and after Okinawa

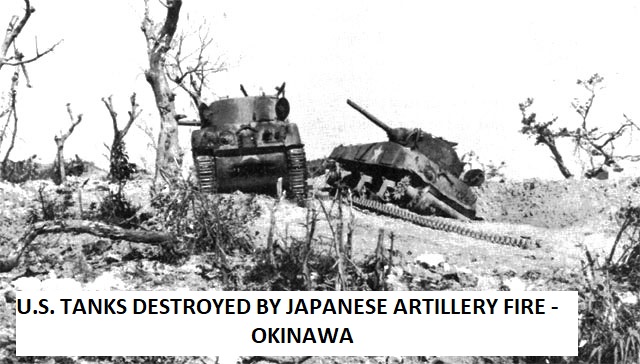

The enemy was often unseen, hidden in caves and spider holes. High points were taken and lost. Tanks were destroyed by artillery or mines. The killing seemed to go on forever. The horrific battle in Okinawa’s “Death Valley,” resulted in death to hundreds, perhaps thousands of Japanese. “There were 500 to 700 bodies, all over the place,” Spike remembered.

Japanese artillery

Tank under artillery fire

Finally, the weight of American force pushed the remaining Japanese into a smaller and smaller area. By the end of May 1945, over 50,000 Japanese had been killed – yet the battle was far from over. The 6th Marine Division were loaded on ships and made another amphibious landing, helping seal the doom of the remaining defenders

Suddenly, it was over. The cost was dear. Over 12,000 soldiers, sailors and marines died in the fighting and defending against kamikaze air attacks. It is estimated that over 110,000 Japanese died, either in the fighting or by suicide. Sadly, Okinawan civilian losses were huge – well over 100,000. Adding to that, the islanders had been told repeatedly that Americans would rape the women and kill the men. Those Okinawans not used as slave labor and killed during the fighting, had to be convinced that what had been told them was a lie. “The civilians just knew we were going to kill or rape them, because that is what they’d been told.” Instead, Americans went out of their way to assure of the opposite. GIs and marines handed out water, food, and medical supplies to everyone in need.

Like thousands of other fighting men, Spike was diagnosed with “combat fatigue.” He shipped home to USNH San Leandro, dealing with what we now call PTSD. Finally, in December 1945, Sergeant Spike Strawn was honorably discharged from the United States Marines. He’d lost over thirty pounds while in combat and was suffering from malaria. Of his 1022 days in the Marine Corps, 137 had been in some of the worst combat experienced in World War II.

With millions of others, Spike returned home. After blowing of steam “honky-tonking” for about six months, he married and began a family. The drought of the early 1950s made him re-think farming. Like his father Dill, Spike did what was necessary to ensure his family’s well-being. He became a feed salesman for Capitol Feed at one dollar an hour. It wasn’t unusual to work seventy to eighty hours a week. Eventually, Spike started his own fertilizer company, which he operated until he retired.

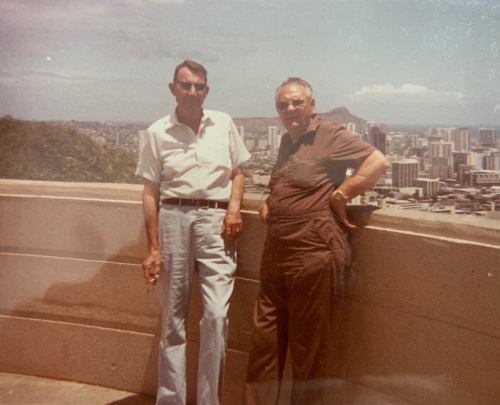

In 1994, Spike and his buddy Fred Hinnenkamp, flew to the Pacific and revisited some of the areas he’d trained in or fought in. I wonder what memories, good and bad, the trip brought to his mind.

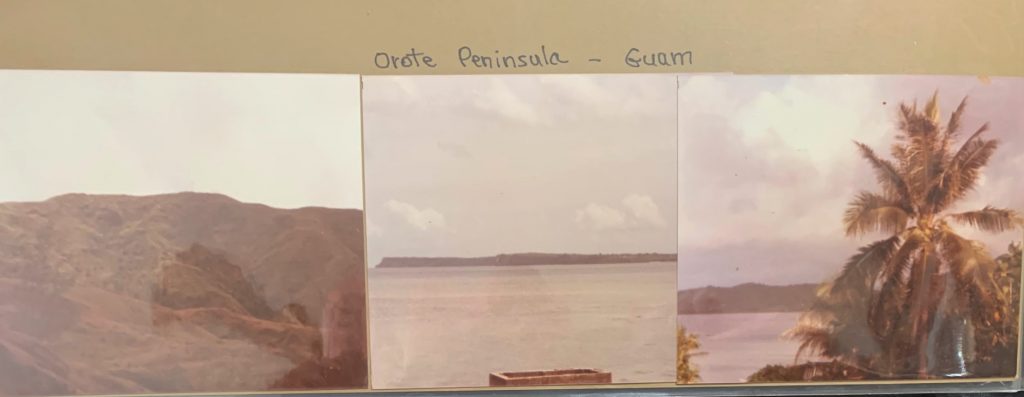

Orote Point, Guam 1994

Where the 22nd Marines landed in 1944

Spike and Fred Hinnenkamp, 0ahu 1994

Spike and Japanese tank 1994

Spike Strawn’s proudest achievement was that “he helped raise three good kids.”

I visited Spike at his apartment a year before he died. He showed me a large United States Marine Corps blanket covering his bed. I believe his second proudest achievement was serving his country in the USMC.

Semper Fideles, Sergeant Strawn.