DANIEL ROYSTON “JACK” CHAMBERLAIN

Jack Chamberlain was the son and oldest child of James (Jim) Chamberlain and Scottie (Royston) Chamberlain of McMahan. He was born on February 5, 1919. His younger siblings were Sarah Irene (1920-1992), James Scott (1923-1986) and Henry Lyndon (1926-1987). Jim Chamberlain ran a general store in McMahan. He would live to the age of 99 and be remembered fondly by many whose families were kept alive by Jim’s generosity during the Great Depression.

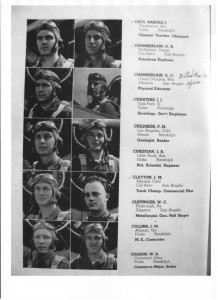

After graduating from Lockhart High School Jack became a Fightin’ Texas Aggie. He was a cadet in Headquarters Battery, Second Battalion Coast Artillery. He completed two years of study and then quit and enlisted in the Army Air Corps as an aviation cadet on December 30, 1940. On the date of his enlistment he stood 5’10” tall and weighed 142 pounds. His basic and primary training took place at the private contractor-run Cal Aero Flight Academy (later Chino Airport, California) and at Goodfellow Field in San Angelo.

His letters home to his mother reflected the natural progression of a young man from pre-war aviation training to a military pilot in a wartime setting. In January of 1941 he wrote from California of a cadet who failed to fasten his seat belt, and who fell out of an open cockpit trainer when it went inverted. Fortunately, the

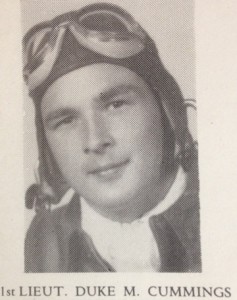

student was wearing a parachute and survived. He mentioned rumors that ‘dodoes’ (apparently the name given new trainees) were going to be washed out at a high rate because of the lack of aircraft. Later than month, he confessed that “the instructors say that according to the law of averages we are past due for some dead cadets.” In that he was most certainly correct. He was allowed to solo with less than four hours of dual instruction. Nonetheless, he survived Basic and Primary training and received his wings on August 15, 1941 at Kelly Field in San Antonio, graduating in Class 41-F. Although he had not graduated from college, Kelly’s class album, “The Gig Sheet,” listed him as a petroleum engineer – probably based on his unfinished studies at A&M.

Jack was transferred to Wheeler Army Airfield on Oahu, Hawaii and assigned to the newly activated 73rd Pursuit Squadron, 18th Pursuit Group. The Group was part of the Hawaiian Interceptor Command. The squadron aircraft contained obsolete P-36 Hawks as well as the newer P-40. The P-40, soon to be obsolescent, was nonetheless an excellent fighter in the hands of experienced pilots such as the Flying Tigers, and British and Free French flying in North Africa. Jack thrilled at its speed and maneuverability, but he also was one of many who confessed to a healthy fear of its quirks. On November 9, 1941 he wrote, “The more I see a P-40, the more cautious I become when flying it. It has a very vicious and unorthodox spin and it comes out at its own leisure.”

In the ramp-up to World War II Jack met many college mates: “The Aggies must be everywhere, because I see someone I know everywhere I go,” he wrote in early November 1941. Like any proud Aggie, he was elated that the University of Texas had just been beaten by Baylor and hoped for the same result with A&M on Thanksgiving (alas, it was not to be). By now, everyone in the military expected war, but the tone of his letters home still did not possess any sense of urgency or alarm. In another pre-war letter, he told of enrolling in Jiu jets classes, of pistol shooting, and the expectation of aerial gunnery school “in the spring.” He purchased a car for $600.

The casual pace of the military training would change on December 7, 1941.

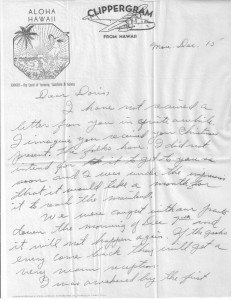

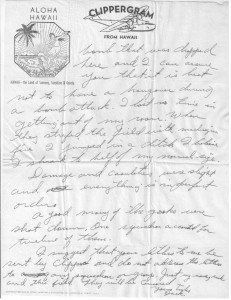

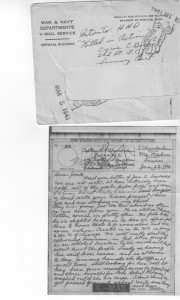

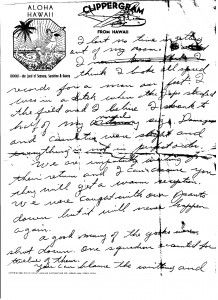

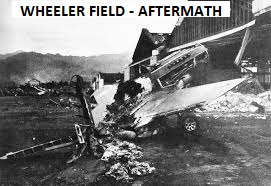

In a letter dated December 15, 1941 sent by Pan American ‘Clippergram’ (military rate of 6 cents per ½ ounce for first class mail) he explained to a young lady named Doris (whom he was apparently sweet on) that “[w]e were caught with our pants down the morning of Dec 7th and it will not happen again. If the [Japanese] ever come back they will get a very warm welcome. I was awakened by the first bomb that was dropped here and I can assure you that it is best not to have a hangover during a bomb attack. I lost no time in getting out of my room. When they strafed the field with machinegun fire I jumped in a ditch. I believe I shrank to half of my normal size.” Jack minimized the damage to Wheeler Field. All 18 of the squadron’s P-36s were destroyed on the ground. His letter to his mother (presumably a teetotaler) of the same date makes no mention of the hangover. Neither letter described the horror of damage inflicted by sneak attack.

With the onset of war came a new urgency. And also a request: “I need an insignia for my plane [presumably a P-40 at this stage]. It should be approx. 5 in. in diameter. As a suggestion – a mule kicking up his hind legs.”

Early 1942 was spent in training and air patrols over Hawaii. It appears to have become monotonous.

On June 1, 1942, he mentioned that his friend Mansel Williams had been promoted to first lieutenant at the same time as him (March 1, 1942). Mansel would be killed in Italy in December of 1943 while part of the 36th Division. Jack’s pay was now $275, a princely sum when coupled with housing and food allowances of $78. Jack sent money home to assist in Irene’s college expenses. That month he shipped home two footlockers of civilian clothes. They were no longer needed.

Shortly after the Battle of Midway, Jack’s squadron was transported to Midway Island and on June 22, 1942 flew off the deck of the USS Saratoga for a two-month rotation on the island, relieving a battered Marine combat squadron. It then rotated back to Oahu. While on Midway, he expressed his opinion of younger brother James’ desire to join the Navy: “I’m agin it.”

Jack volunteered for a new squadron, the 6th Night Fighter  Squadron, in late 1942. Rumor abounded as to its ultimate assignment. And during this time, Doris found another beau. Like so many young men, he apparently received a “Dear John” letter. He inquired of Scottie if she knew what had happened.

Squadron, in late 1942. Rumor abounded as to its ultimate assignment. And during this time, Doris found another beau. Like so many young men, he apparently received a “Dear John” letter. He inquired of Scottie if she knew what had happened.

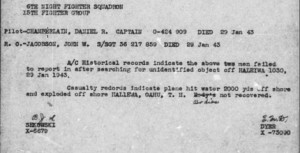

He was killed on January 29, 1943. He had been promoted to captain a few weeks before his death. The accident report (#16268) contains little information. Oddly, it does not even identify the type of aircraft Jack piloted:

The Entirety of the Investigation

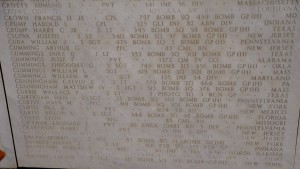

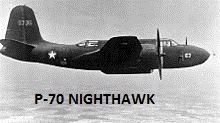

Research indicates that Jack and Sergeant Jacobson were flying a variant of the A-20 Havoc designed as a night fighter, designated P-70 Nighthawk with a two man crew. A shipment of P-70s had been received by the squadron in September of 1942. Jack and Sgt. Jacobson went up to check on an unidentified object in the waters near Pearl Harbor and lost control, crashing and exploding off Oahu. Jack is memorialized on Wall C, Tablets of the Missing, in the National Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl) on Oahu, Hawaii. He had not reached his 24th birthday.

Inscription-Tablets of the Missing

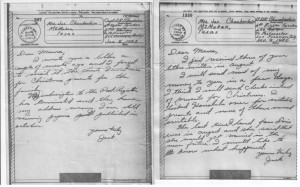

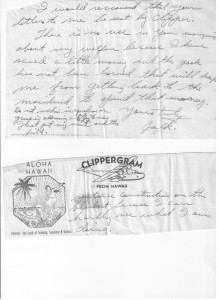

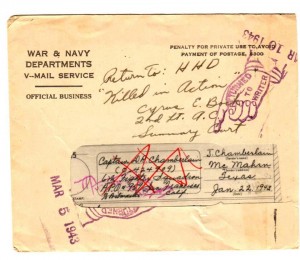

Scottie’s last letter to her son, dated January 22, 1943 was never received. It was returned to her by the War Department, marked “Killed in Action.”

Scottie’s Last Letter To Her Son