1944

2017

COLONEL STAN REECE

AN INCREDIBLE LIFE OF SERVICE TO HIS COUNTRY AND COMMUNITY

By

Todd Blomerth

It was early 1953. The Allies were locked in vicious combat with communist forces along a line across the Korean peninsula. Ten miles inside enemy lines, Captain Stan Reece was in the back seat on an AT6 “Texan” artillery spotter aircraft. After flying over thirty missions, the 6147th Group commander had made Captain Reece the group’s operations officer. The unit’s casualty rate was too high, and as operations officer, Captain Reece was told to check out each pilot, to ensure all were qualified and performing at the high standard needed. Stan sat in the rear seat of the two-seater aircraft, where an Army forward observer usually was placed. He was evaluating the skill and proficiency (we’ll call him Jones), trying to ensure Jones would not be another casualty while providing the US Army with an aerial platform for forward observers.

Very concerned about the Jones’s too-casual attitude about the enemy’s willingness to shoot down “low and slow” unarmed intruders, Captain Reece instructed him to make corrections. Before that could happen, the AT6 took 37mm antiaircraft rounds that damaged its right wing and flipped the aircraft onto its back. Smoke poured into the cockpit Jones failed to respond to Reece’s intercom, and Captain Reece was forced to take over piloting the wounded airplane. Flinging open the canopy to clear blinding smoke, Captain Reece fought to regain control of the damaged aircraft,. He prayed the wounded bird would get the two back across the front lines before it came apart. Fortunately, it did.

“Where were you when I needed you to flying the airplane?” he frantically demanded of Jones. Finally responsive, Jones meekly replied, “I was scared.”. “Well I was too,” responded Captain Reece. “But you still have to fly the plane!”

As Captain Reece landed, the ground crew furiously waved him away from revetments and parked aircraft. It turned out that the anti-aircraft rounds had ignited white phosporus rockets under the aircraft’s wings, used to spot enemy positions. The ground crew’s well founded fear of an horrific explosion and fire was not realized. Fire crews extinguished the flames, as a forward observer pilot and his evaluator leapt from the plane. Captain Reece made sure Jones never flew with the unit again. It was a tough call, as Jones was a friend, but the only one to make.

Sixty-four years later, Colonel Stan Reece sat in his living room, telling me of his life. Now ninety six years old, he expresses some doubt as to why he is being interviewed. “I don’t think my career was all that interesting,” he tells me.

This is his story. You decide for yourselves whether his belief is correct.

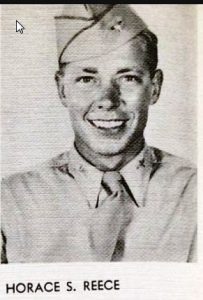

Horace Stanley “Stan” Reece was born in the community of Martin’s Mill, Van Zandt County, Texas on September 21, 1921. He was the oldest of five children of Flake Elijah Reece and Nettie (Lancaster) Reece. Flake and Nettie taught school for a period of time. Flake was also a farmer, but later moved the family to Athens, Texas where he owned a garage. Stan and his younger siblings, Charles, Billy, Bonetia and Mary Jo all graduated from Athens High School. Like all children of the Depression, Stan knew about hard work. When he wasn’t in school, he worked for his dad as a mechanic. He graduated in 1940, and then worked construction in Ft. Worth and at Camp Wolters.

On June 30, 1942, Stan was sworn into the United States Army Air Forces as an aviation cadet. Because of training facility shortages, he was told to go home. “They said they’d call me in a month,” he recalls. He worked in his dad’s garage for almost six months before he received orders to report to the San Antonio Aviation Cadet Center (later Lackland Air Force Base). Stan took to the air naturally. Without bragging, he calmly states, “I was a very good pilot.” After Basic at Brady, Texas and Primary at Waco Airfield, he finished second in his class at Advanced training at Eagle Pass Army Airfield. With over twenty hours already in a high-powered P-40, he hoped for a combat assignment. Enamored with the monstrous P-47 Thunderbolt, he tried for an assignment flying that fighter. No luck. Then he applied for a unit flying the magnificent P-51 Mustang. Again, no luck. The Army Air Forces had other ideas. 2nd Lieutenant Stan Reece was assigned as an instructor pilot at Randolph Army Airfield, outside of San Antonio. It was a bitter disappointment, but just one of the breaks. He loved flying, and was a natural teacher.

The stateside duty proved a blessing in disguise. In mid-1944 he was diagnosed with osteomylitis. Prior to the advent of strong antibiotics, the best someone with this dangerous bone infection could hope for was to survive with an amputation. Stan was lucky, as penicillin was coming available. It still took fifteen months in the hospital to be cured. “They didn’t know how long I had had the infection in my leg before it was discovered,” he recalls. By the time he was released in October of 1945, the war was over. The interminable time recovering was not all a loss. Stan met and married a beautiful Army officer (and nurse) – Edith Clark, from Prairie Lea. Their happy marriage lasted for sixty-six years. Edith died in 2011. They have two children. Ralph was born in 1946. Jacqueline was born in 1948.

Because of his skills, Stan was one of the small minority of pilots who were allowed to stay in the Army Air Force after World War II, as the services drastically reduced manpower. The newly married pilot, soon to be a father, was assigned to post-war Germany, first in Wiesbaden, and then in Kassal. He had several assignments.

Then the Soviet Union and its East German lackeys began closing road and canal access to areas of Berlin controlled by the French, British, and Americans. With one and one half million Soviet troops surrounding the former capital of Nazi Germany, Stalin felt sure that he could force the Western Allies out of Berlin, subjecting its citizens to the communist rule beling inflicted on East Germany. The Americans and British undertook to fly into the beleaguered city over 6000 tons daily, of food, supplies and coal. In was considered an impossible task.

Beginning in late June, 1948, with C-47 Dakotas, and later with C-54s and other, heavier transports, pilots flew narrow air corridors at three minute intervals, day and night, for almost one year. Airplanes got one shot at landing. Upon landing in West Berlin, engines were kept running, air crews remained in their transports, as Berliners unloaded the precious food and supplies. Then it was an immediate take-off and return to friendly territory. A missed approach meant returning to West Germany, fully loaded. There was no room for error.

Despite Soviet harrassment, eventually the Airlift was moving over 11,000 tons a day! In April of 1949, the Soviets gave up. Berliners actually had a surplus of food and supplies. Stan Reece flew over twenty flights in and out of Berlin. His younger brother Charles, also an aviator, was part of the all-out effort. The Airlift is one of the proudest moments in our nation’s history.

Captain Reece was then assigned to Tinker Air Force Base as an instructor pilot. He had flown and mastered all sorts of aircraft. A small sampling: P-40, P-47, and P-51 fighters; A-26, B-25 bombers; C-47, C-54 transports, AT-6 trainer. Because of the rush to get pilots into aircraft in World War II, and the budget and manpower cuts afterward, training had suffered grievously. Stan recalls that “many of these pilots, including some who’d flown in World War II, weren’t trained properly.” What better man to help fix the problem than someone of Stan’s stature and reputation?

Then, war in an unexpected place threw the United States in a frenzied effort to save South Korea from subjugation by North Korean, and later, Chinese communists. Bidding farewell to his wife and kids, Captain Reece arrived in the war-torn Korean peninsula in 1952. He was assigned to the 6147th Tactical Control Group. He flew unarmed AT-6 “Texans” over enemy lines, with an Army artillery forward observer onboard. In over twenty-five missions, he was shot at “plenty of times” but never hit. That is, until he was a check pilot for “Jones,” and was almost shot out of the sky over enemy lines.

In September of 1953, Captain Reece was back in the States. The 1950s were a transition period for the United States Air Force. Propeller driven aircraft were phased out, and jets of all types were tested. There were fewer straight winged aircraft, as jets’ speeds required swept wings. Thousands of aircraft were moved back to the continental United States from overseas. Some were scrapped, some were sold to friendly countries, some were given to Air National Guard units, and some were retrofitted. Stan was part of this complicated and often dangerous task. Between 1953 and 1962, Stan took on hundreds of ferrying operations.

1950s were a transition period for the United States Air Force. Propeller driven aircraft were phased out, and jets of all types were tested. There were fewer straight winged aircraft, as jets’ speeds required swept wings. Thousands of aircraft were moved back to the continental United States from overseas. Some were scrapped, some were sold to friendly countries, some were given to Air National Guard units, and some were retrofitted. Stan was part of this complicated and often dangerous task. Between 1953 and 1962, Stan took on hundreds of ferrying operations.

Assigned to the Military Air Transport Command (MATS) and its 1708th Ferrying Wing, he coordinated and flew transports to and from overseas air force units. One trip nearly got him killed. He and his crew flew a new C-119 to Japan. They exchanged it for one that was on its last legs. Taking off, the overloaded aircraft needed all the runway and overrun to make it into the air. Then, the crew discovered that the extra 900 gallon tank in the fuselage was leaking fuel. Stan was piloting a potential fiery bomb. It turned out that someone had installed a fuel vent pipe the wrong way. Remaining cool, Stan landed the plane without incident. The crew fixed the problem, and made it to Hawaii before the tired bird gave up the ghost. He and his crew caught another flight home.

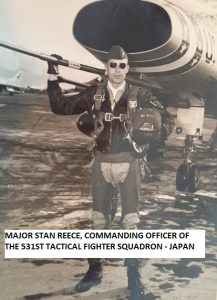

After an assignment at Andrews AFB, Major Stan Reece and family  spent three years in Japan, where he commanded the 531st Fighter Squadron flying F-100s. Later, as the Wing operations officer. He oversaw pilots flying RF-101s, and AD-102s. As he recalls, most of his pilots were “a bunch of kids.” They were lucky to have a proficient and demanding boss, who expected nothing less than the best, and made sure they achieved it. The Wing was equipped with nuclear weapons.

spent three years in Japan, where he commanded the 531st Fighter Squadron flying F-100s. Later, as the Wing operations officer. He oversaw pilots flying RF-101s, and AD-102s. As he recalls, most of his pilots were “a bunch of kids.” They were lucky to have a proficient and demanding boss, who expected nothing less than the best, and made sure they achieved it. The Wing was equipped with nuclear weapons.

Stan knew that to move up the promotion ladder, it was expected that he be proficient in all areas of aviation. Often that meant accepting assignments to non-glamorous jobs. Because of his willingness and skill, he was often picked to ‘clean up’ situations, particularly those where pilots’ lives were in danger because of inefficiency or poor training standards. The 1960s found him and the family at Eglin AFB in Florida, in another of those roles.

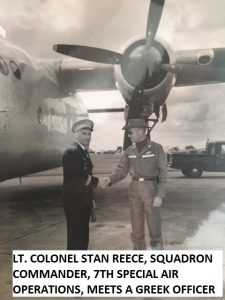

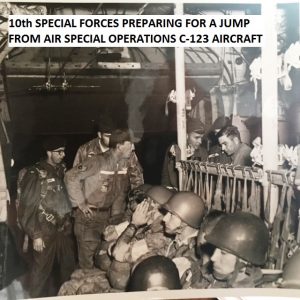

His next assignment put Lieutenant Colonel Reece back in Germany. He was the first commander of the 7th Air Special Operations Squadron, tasked with supporting the 10th Special Forces, one of the first Green Beret units. Comprised of a hodgepodge of propeller-driven aircraft, and designed for special operations, the squadron’s pilots and crews helped the SF forces conduct airborne training operations. “A large percentage of the Special Forces unit were first generation Americans from Eastern Europe. They spoke with thick accents. They hated the communists,” recalls Stan. Maximum flexibility best describes the operations of the Squadron. It was a heady time, as the United States continued its experiment with small and specialized forces. Stan spent two and a half years as squadron commander. His Army counterp art was “an old OSS [the World War II predecessor to the CIA] colonel. We got along famously.” Practice for insertions and extractions behind the Iron Curtain, providing air support for British Special Air Services commandos, conducting parachute drops, and retrofitting aircraft for unorthodox warfare made life, in Stan’s word, “interesting.” That has to be a understatement

art was “an old OSS [the World War II predecessor to the CIA] colonel. We got along famously.” Practice for insertions and extractions behind the Iron Curtain, providing air support for British Special Air Services commandos, conducting parachute drops, and retrofitting aircraft for unorthodox warfare made life, in Stan’s word, “interesting.” That has to be a understatement

Military spouses have unenviable roles to play. Stan was transferred many times during his career. Even when assigned to one base, duties often took him away from his family. A full-time mom who often had to parent alone, Edith was the rock that kept the Reece family together. Edith’s duties expanded when Stan was a unit’s commanding officer. She then became a mentor, advisor, and, occasionally, a shoulder to cry on. It was tough duty, and deeply appreciated. Stan is unstinting in his praise of Edith. “Edith was a stabilizing influence on many young wives,” Stan recalls.

Between 1966 and 1968, Lieutenant Colonelr Stan Reece  commanded the 492nd Tactical Fighter squadron, based in England. Flying F100s, the squadron participated in numerous NATO exercises. These included deployments to Bodo, Norway, Aviano, Italy, and Ishmir, Turkey. Joint exercises, intended as training for possible response to Soviet aggression, came at the heighth of the Cold War. The training was arduous, and demanding. If war came, the Soviets had a numerical superiority that would test the very fiber of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s ability to defend the free countries in western Europe, Turkey, and Scandinavia.

commanded the 492nd Tactical Fighter squadron, based in England. Flying F100s, the squadron participated in numerous NATO exercises. These included deployments to Bodo, Norway, Aviano, Italy, and Ishmir, Turkey. Joint exercises, intended as training for possible response to Soviet aggression, came at the heighth of the Cold War. The training was arduous, and demanding. If war came, the Soviets had a numerical superiority that would test the very fiber of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s ability to defend the free countries in western Europe, Turkey, and Scandinavia.

It was inevitable that an aviator of Stan Reece’s ability would end up  in Vietnam. Saying goodbye to Edith, he reported for duty at the Phu Cat Air Base. A new airfield, capable of jet powered aircraft, it was completed in late 1967. Lt. Colonel Reece was assigned as the 37th Tactical Fighter Wing’s operations officer. Part of the unit was the Iowa National Guard’s 174th Tactical Fighter Squadron. Equipped with the now aging and quirky F100s, the Wing flew interdiction and combat support missions. In just six months, Stan flew 135 combat missions. Most were in South Vietnam, but over thirty were in Laos, and there were a few into North Vietnam. Thankfully, he came through that experience in one piece. His final six months in Vietnam were at 7th Air Force Headquarters in Saigon.

in Vietnam. Saying goodbye to Edith, he reported for duty at the Phu Cat Air Base. A new airfield, capable of jet powered aircraft, it was completed in late 1967. Lt. Colonel Reece was assigned as the 37th Tactical Fighter Wing’s operations officer. Part of the unit was the Iowa National Guard’s 174th Tactical Fighter Squadron. Equipped with the now aging and quirky F100s, the Wing flew interdiction and combat support missions. In just six months, Stan flew 135 combat missions. Most were in South Vietnam, but over thirty were in Laos, and there were a few into North Vietnam. Thankfully, he came through that experience in one piece. His final six months in Vietnam were at 7th Air Force Headquarters in Saigon.

Returning to the United States, newly promoted Colonel Stan Reece finished out a most colorful and exciting career in St. Louis, Missouri as Wing Advisor to the Air National Guard. He retired, after 30 years of service, in 1974.

Edith longed to return to her Texas and Caldwell County roots. In 1975, the Reeces purchased forty-nine acres of land outside of Luling. Anyone who knew him realized that Stan Reece wasn’t someone to sit back and let the world pass him by. He raised cattle. He served on the Luling Independent School District Board of Trustees for twenty-four years, of which nineteen he was the Board’s president. He joined the Luling Kiwanis Club in 1975 and remains active today. He was an officer on the Caldwell County Farm Bureau, and served on the Caldwell County Agent supervisory board for many years. Trying to track him a couple of weeks ago, I found him awash with plans for Night In Old Luling.

Stan will tell you his has been a blessed life. In 2014 at the young age of ninety three, he tied the knot for the second time when Madeline Manford, a dear family friend of many years and a widow, agreed to be his bride.

So this is a short-hand version of Stan’s life (so far). After reading it, I know you will agree that Colonel Stan Reece has indeed led a most incredibly interesting and fruitful life. He truly is a shining example of the best of the Greatest Generation. If you can catch him, please be sure to thank him for his service to his country and community.