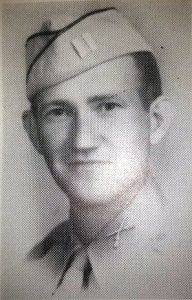

JACK STOREY LIPSCOMB

by Todd Blomerth

Jack Storey Lipscomb was born in Lockhart, Texas on November 25, 1925. He was the son of John William Lipscomb, Sr. and Corinne Cardwell Storey Lipscomb. The two had married in 1919, when John was 28 and Corinne was 23. Jack’s family lineage encompassed many of the ranching and farming pioneers of Caldwell County and South Texas. Jack had two siblings, older brother John W. Jr. and younger sister Beulah Jean. The Lipscomb families owned and operated several cotton gins and mercantile stores in northern Caldwell County.

John Sr. enlisted in 1917 at the beginning of America’s involvement in World War I. After being discharged from active service in early 1918, he worked in the family businesses. He also became an officer in the Texas National Guard. The Lipscomb family lived on South Main Street, and attended Lockhart’s Presbyterian Church.

In March of 1935, John Sr., by now a captain, was appointed by Texas Governor Allred as the custodial officer of the Texas National Guard Encampment near Palacios, in Matagorda County, and the Lipscomb family moved from Lockhart. Camp Hulen, as the encampment was more commonly called, served as a Guard training facility until nationalized. It then became a U.S. Army training facility until early 1944 when it was converted to prisoner of war camp for captured Germans.

Jack thrived in Palacios. He played football at every level of schooling allowed. At one point he was nicknamed the “Mighty Mite,” when he quarterbacked the grammar school team in the late 1930s. . He was quarterback of the Palacios Sharks when the team was district co-champion his junior year. He was described by one admirer as a “happy, tousle-headed, freckled faced lad.”

But Lockhart was still considered home, and the family was often in Caldwell and other counties where the large interwoven family owned land. A June 1939 Post Register story reported that Jack’s grandmother, Mrs. A.A. (Beulah Cardwell) Storey, his mother Corinne, and sister Jean traveling to the family ranch in Zavala County, to drop off Jack, older brother John, and cousin, James Storey where the boys would spend a month. The Post-Register stated that “[t]he boys are being chaperoned by Sr. Estanislau Gomez and they are expecting a great time.” That “great time” included a lot of hard work.

John Lipscomb Sr.’s military duties included inspecting National Guard units, including the 141st Infantry Regimental detachment in Lockhart. When Camp Hulen was nationalized in 1940, and by now a major, he transferred to Camp Bowie, where he was the base recreation officer. In 1942, Major Lipscomb transferred to Austin, where he served as coordinator of the staff of Adjutant-General J.W. Page in the Selective Service work of that office. By 1941 older brother John Jr. was attending Texas A&M, and about to be selected for the United States Naval Academy. Jack and younger sister Jean along with their mother, continued to live in Palacios so Jack could finish high school (and continue to play football).

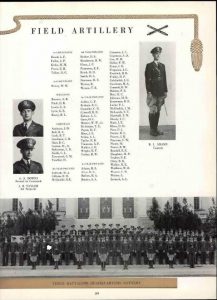

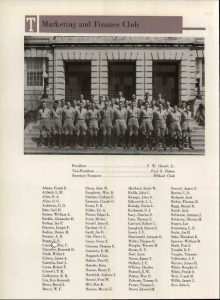

Jack graduated from high school in 1943 and enrolled in the Corps of Cadets at Texas A&M. Corrine and Jean re-joined John Lipscomb, Sr. in Austin where John Sr. and Jean bought a new home in Highland Park West.

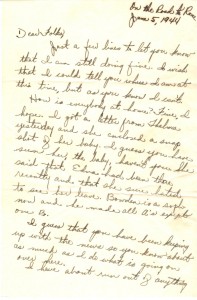

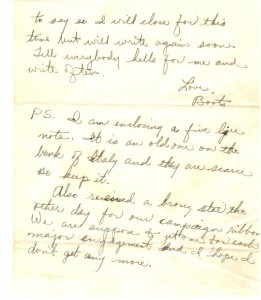

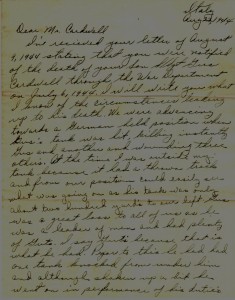

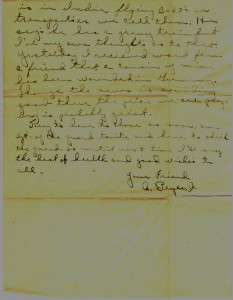

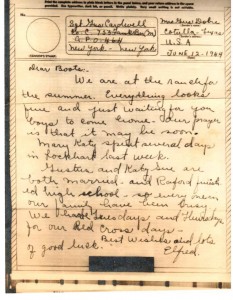

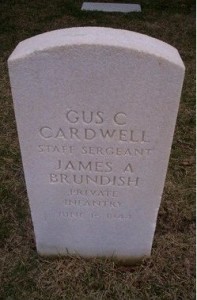

Jack quit A&M after one year and enlisted in the United States Marine Corps on February 21, 1944. He completed boot camp at Camp Elliott, California, where he was occasionally able to be meet up with his cousin John Cardwell, also a marine stationed nearby. John Cardwell would eventually serve as a machine gunner on a Dauntless dive bomber. John Cardwell’s older brother Gus served with a tank battalion and was killed in Italy in 1944. Jack sent a letter to John expressing his grief over Gus’s death.

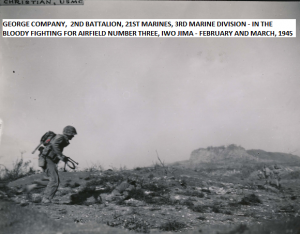

Jack finished boot camp, qualified as an expert on the M-1 rifle and the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) and was shipped to Hawaii. He then was sent to the island of Guam in the Marianas in mid-August, 1944 and was assigned to Company G, 2nd Battalion, 21st Marines, 3rd Marine Division. The division had just taken part in the American re-taking of the island of Guam from the Japanese. The invasion cost the Americans over 1700 dead and 6000 wounded. The 3rd Division suffered 677 deaths and over 3600 wounded. The nearly 19,000 Japanese defenders were virtually wiped out. After several months of refitting, the 3rd Division was again ready for another island landing. It would be its bloodiest.

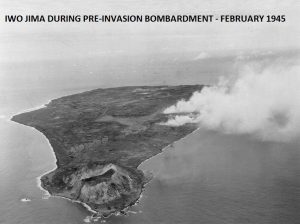

Iwo Jima is a tiny, sulfurous blot of land in the Bonin Chain less than 600 miles from the Japanese main islands. With the Marianas in US hands in 1944, new American B-29 bombers now had bases from which to attack the Japanese homeland. A massive bombing campaign began to take the war to Japan’s cities and industrial centers.

Iwo Jima was important to the Japanese because it lay athwart the air route from the Marianas to Tokyo, and served both as an early warning site, and an interceptor location for fighter aircraft. To the Americans, Iwo Jima’s location only 650 nautical miles from Tokyo meant it was ideally located to recover disabled or damaged B-29s returning from bombing runs over Japan. It was also close enough to allow P-51 fighters to escort the B-29s all the way to Japan. At first glance, Iwo Jima appeared to be a difficult place to defend. But the Japanese had proved masters of island fighting. The bloodbaths at Tarawa and Peleliu had taught the Americans that.

Intelligence figures estimated that at best the Japanese held the ‘dry wasteland of volcanic ash that stinks of sulfur’ (as James Bradley described it in Flags of Our Fathers) with only 12,000 troops. Hardly a small number, but 70,000 Marines seemed to be more than enough to overcome the defenders. American intelligence estimates conservatively stated that one week was all the time needed to secure Iwo Jima and its three airfields. But those intelligence estimates were wrong, and badly so. The actual number of defenders had grown to 23,000 before the island was blockaded.

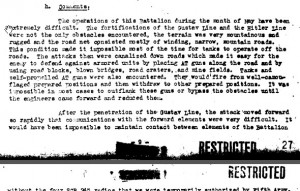

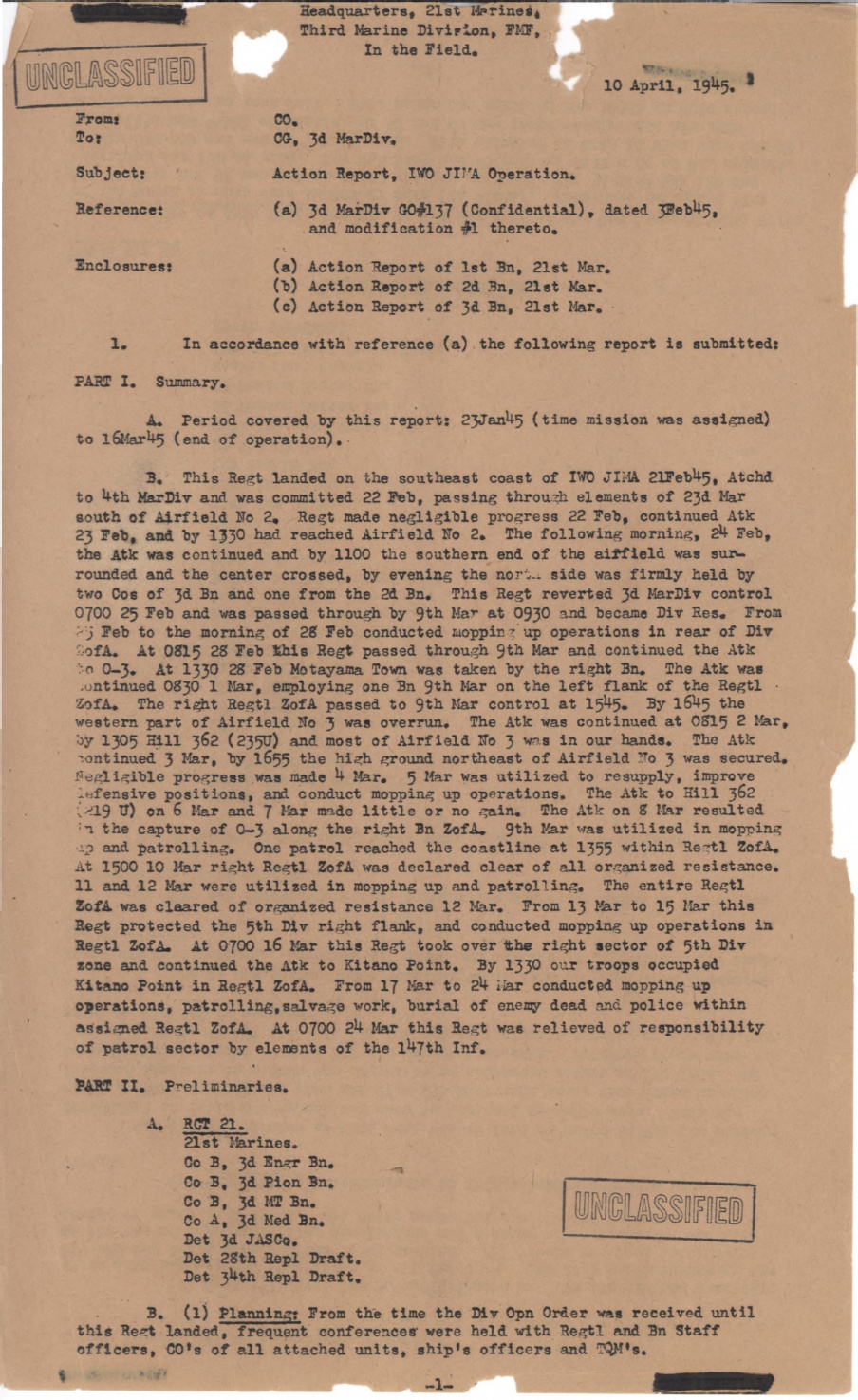

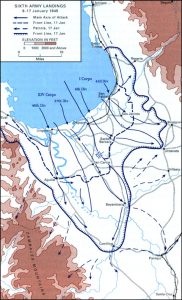

The 3rd Division embarked from Guam on the USS President Adams  on February 12, 1945. It was designated as the invasion’s floating reserve. Weeks of pre-invasion ‘softening up’ of defenses proved fruitless. The 4th and 5th Divisions hitting the beaches on February 19th had so many casualties that the 3rd Division was ordered ashore on the 20th. The mayhem on the beaches wouldn’t allow its landing, so it tried again the following day. From February 21st on, Jack and his men were in continuous combat. The Americans quickly cut the island in two. But casualties soon reached epic proportions. The well trained and concealed defenders, fighting from a maze of caves, tunnels and pillboxes, supported by mine fields and interlocking fields of fire meant some units were soon down to a fraction of their original strength. By March 2nd, Jack’s battalion had less than 300 men able to fight out of the 1200 who had come ashore. It had lost every company commander and all but one company executive officer. On March 3rd, the 21st Marines took the unfinished Airfield No. 3, and were able to seize the nearby high ground northeast of the field. It was here that Jack was killed.

on February 12, 1945. It was designated as the invasion’s floating reserve. Weeks of pre-invasion ‘softening up’ of defenses proved fruitless. The 4th and 5th Divisions hitting the beaches on February 19th had so many casualties that the 3rd Division was ordered ashore on the 20th. The mayhem on the beaches wouldn’t allow its landing, so it tried again the following day. From February 21st on, Jack and his men were in continuous combat. The Americans quickly cut the island in two. But casualties soon reached epic proportions. The well trained and concealed defenders, fighting from a maze of caves, tunnels and pillboxes, supported by mine fields and interlocking fields of fire meant some units were soon down to a fraction of their original strength. By March 2nd, Jack’s battalion had less than 300 men able to fight out of the 1200 who had come ashore. It had lost every company commander and all but one company executive officer. On March 3rd, the 21st Marines took the unfinished Airfield No. 3, and were able to seize the nearby high ground northeast of the field. It was here that Jack was killed.

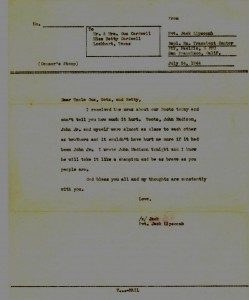

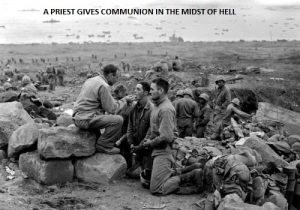

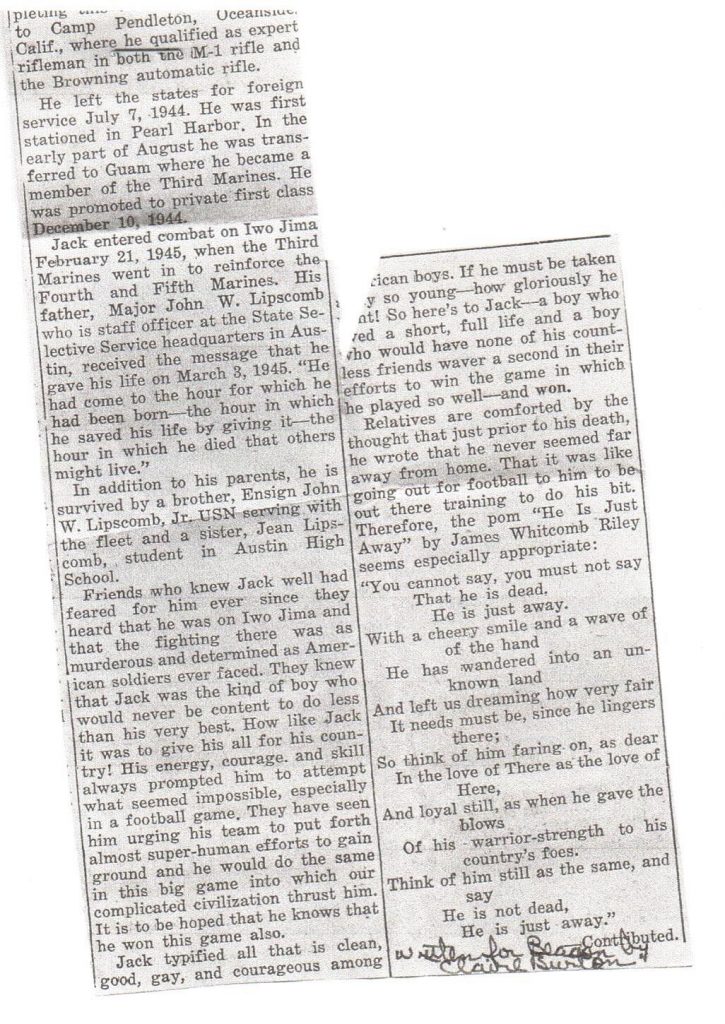

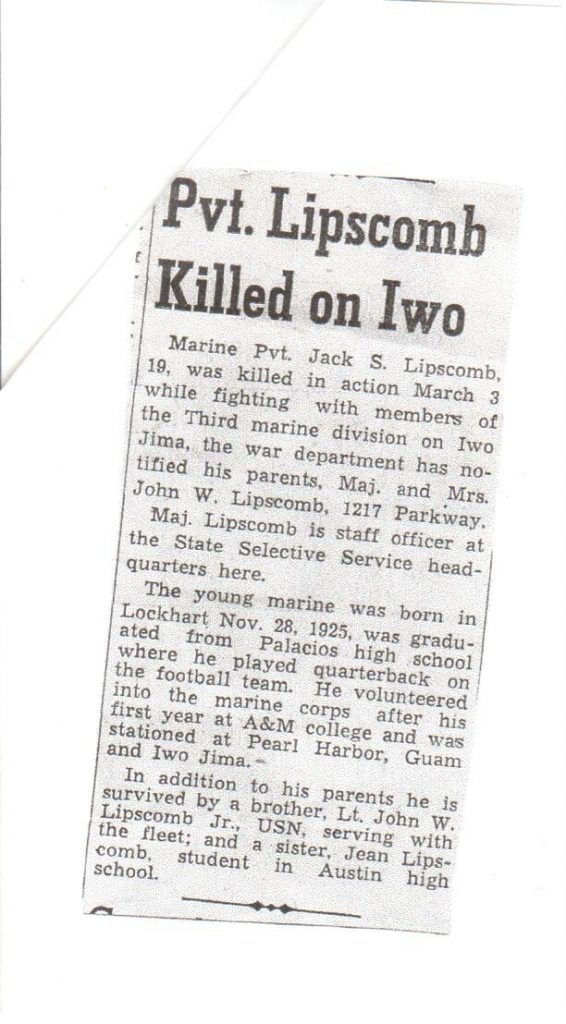

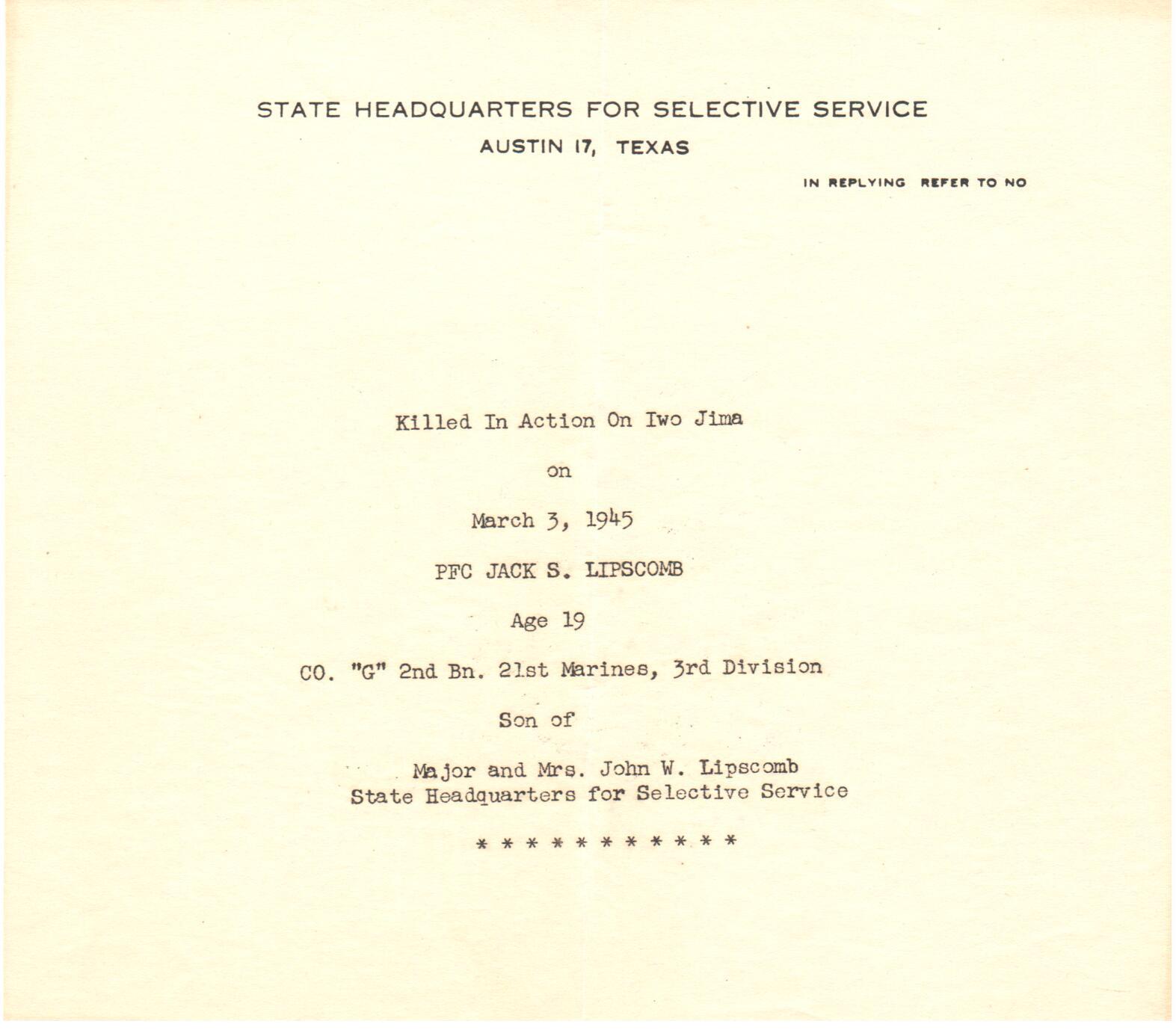

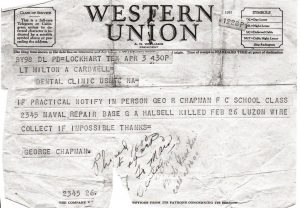

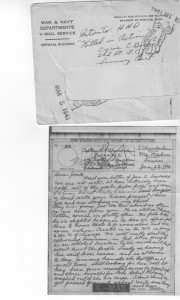

The family received the news of his death shortly afterward. Both Lockhart and Palacios were deeply affected. The Palacios Beacon ran a long tribute to Jack, written by a good friend, Claire Burton. It was re-printed in the Post-Register. The family received many letters of condolence, including several from members of the 21st Marines. Corporal P.A. Shiesler wrote: “I was not with your son at the time of his death, but a buddy of mine was, and told me that Lippy died instantly from a bullet wound. There was no suffering…. I can honestly say that he was doing more than his share when he was on Iwo. He was a good Marine.” The unit chaplain, probably numbed by the last rites given and funerals read, wrote: “You son was killed while in the heat of battle on Iwo Jima on 3 March, 1945 when he was hit in the head by an enemy bullet killing him instantly. He is buried in the 3rd Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima, Row 25, Grave 1484, Plot #6.” He went on to assure the family that after the battle was over, the entire division assembled to bestow honor on its 1,131 dead with three volleys of seven gun salutes, lowering the American flag to half-mast, and the singing of “Nearer My God to Thee.”

Lockhart and Palacios were deeply affected. The Palacios Beacon ran a long tribute to Jack, written by a good friend, Claire Burton. It was re-printed in the Post-Register. The family received many letters of condolence, including several from members of the 21st Marines. Corporal P.A. Shiesler wrote: “I was not with your son at the time of his death, but a buddy of mine was, and told me that Lippy died instantly from a bullet wound. There was no suffering…. I can honestly say that he was doing more than his share when he was on Iwo. He was a good Marine.” The unit chaplain, probably numbed by the last rites given and funerals read, wrote: “You son was killed while in the heat of battle on Iwo Jima on 3 March, 1945 when he was hit in the head by an enemy bullet killing him instantly. He is buried in the 3rd Marine Division Cemetery on Iwo Jima, Row 25, Grave 1484, Plot #6.” He went on to assure the family that after the battle was over, the entire division assembled to bestow honor on its 1,131 dead with three volleys of seven gun salutes, lowering the American flag to half-mast, and the singing of “Nearer My God to Thee.”

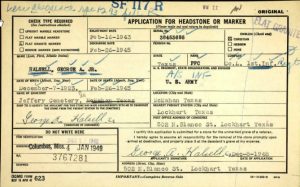

In 1947, the Americans began to disinter the 6800 American marines and sailors buried on Iwo. In 1949, Jack came home. On Sunday, January 16, 1949, Dr. Sam L. Joekel, pastor of Lockhart First Presbyterian Church conducted Jack’s funeral. Superintendant Newsome of the Palacios schools was present. Casket bearers were members of Jack’s Palacios High School football team. Jack is buried in the Lockhart Cemetery.

Jack Storey Lipscomb was nineteen years old.

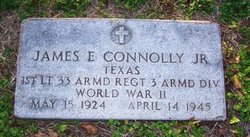

At some point Mack was assigned to Company I, 33rd Cavalry Regiment of the 3rd Armored Division. The 33rd Cavalry’s unit nickname was “Men of War.” It was richly deserved. Described as part of the “massive tank battering ram which made the 3rd Armored Division famous,” its M4 Sherman tanks had a splendid combat record. However, the M4 Sherman also had a reputation as a crew killer, because of its tendency to explode if taking a direct hit. Its nickname was the “Ronson” (a cigarette lighter that was guaranteed to “light up the first time”).

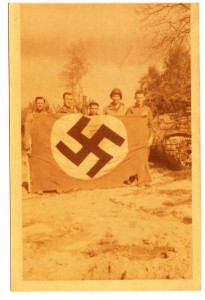

At some point Mack was assigned to Company I, 33rd Cavalry Regiment of the 3rd Armored Division. The 33rd Cavalry’s unit nickname was “Men of War.” It was richly deserved. Described as part of the “massive tank battering ram which made the 3rd Armored Division famous,” its M4 Sherman tanks had a splendid combat record. However, the M4 Sherman also had a reputation as a crew killer, because of its tendency to explode if taking a direct hit. Its nickname was the “Ronson” (a cigarette lighter that was guaranteed to “light up the first time”). combat across Europe served as a meat grinder on Allied forces pushing the Germans back into the Fatherland. The unit had fought across France’s hedgerows reaching Belgium in September 1944. The Division was part of the northern ‘neck’ that held, then closed on the Germans during the winter Battle of the Bulge. It swept into Cologne in March of 1945 and then crossed the Saale River speeding toward the agreed meet-up point with the Russians on the Elbe River. On April 11, 1945 it freed the survivors of the horrific concentration camp of Dora-Mittlebau.

combat across Europe served as a meat grinder on Allied forces pushing the Germans back into the Fatherland. The unit had fought across France’s hedgerows reaching Belgium in September 1944. The Division was part of the northern ‘neck’ that held, then closed on the Germans during the winter Battle of the Bulge. It swept into Cologne in March of 1945 and then crossed the Saale River speeding toward the agreed meet-up point with the Russians on the Elbe River. On April 11, 1945 it freed the survivors of the horrific concentration camp of Dora-Mittlebau.