THE INVASION OF NEW MEXICO

By Todd Blomerth

This is the second in a series of articles about the American Civil War, in this the Sesquicentennial Year of the beginning of that conflict.

On June 1, 1862 the citizens of Prairie Lea and the surrounding area met to make arrangements to “send for our soldiers in Arizona.” This emergency meeting was attended by folks from Caldwell and Guadalupe Counties, and some family names of those attending would be recognizable today: Watts, Hardeman, Pettus, Petty, Allen, Francis, to name a few. ”A committee was then appointed to solicit contributions and make all other arrangements for the trip. “Money, bacon and other supplies were pledged. What prompted this meeting, and why was it necessary for farmers and merchants from the Texas frontier to send help for soldiers 600 miles away?

This is that story.

Background

The war of secession began in Texas with a whimper. At the time, what few federal troops in the state were involved with protecting the frontier against Indian incursions. In San Antonio shortly after Texas’ secession the Federal commander, General David Twiggs, surrendered all US military property in the state to the commissioners of the State of Texas. Union troops were ordered to withdraw. Federal commanders of frontier posts, such as Fort Bliss in what is now El Paso, turned over huge amounts of supplies and quietly left. Most troops either surrendered and were paroled to return north or traded their old blue uniforms for the gray of the new Southern Confederacy. Within weeks, federal power in Texas had been eliminated without firing a shot.

New Mexico and Arizona 1861

Meanwhile, further west in the Territory of New Mexico, which encompassed all of what are now the states of New Mexico, Arizona, and some parts of Utah and Nevada, the outbreak of civil war back East at first seemed a distant threat. The overwhelming numbers of non-Indians in that territory were of Mexican and Spanish descent. Santa Fe, the capital, had a population of only 4653. Albuquerque and Las Vegas each numbered around 1000.

In 1861 few areas of America were as remote and sparsely populated as New Mexico Territory. Its tiny non-Indian population was in constant threat from marauding Apaches. Although seen by many at the time as a desert wasteland of no value, there had been major silver discoveries near Tucson and Tubac in what is now Arizona. The mining towns were filled with gamblers, horse thieves, and murderers, and home to a host of imported vices. Many law-abiding citizens decried the Federal government’s failure to bring order to the area.

Added to this was the constant fear of raids by the Apaches, whose ferocity constantly menaced settlers with the threat of a gruesome death. When Texas seceded, the Overland Mail line as well as many of the federal frontier garrisons quit the territory, further isolating an already remote region and emboldening the Apaches to attack remote regions without fear of retribution. A local reporter, Thompson Turner, six months earlier, had predicted that were this to occur, it would be “a death blow to Arizona.” In April 1861, the Butterfield mail contract, which ran stagecoaches through West Texas, also came to a halt. The Tucson Weekly Arizonian lamented on August 10, 1861 that, “We are hemmed in on all sides by the unrelenting Apache. Since the withdrawal of the Overland Mail and the garrison troops the chances against life have reached the maximum height. Within six months nine-tenths of the whole male population have been killed off, and every ranch, farm and mine of the country have been abandoned in consequence.” Thompson’s prediction was coming true.

Black slavery was virtually non-existent in the Territory, but Miguel Otero, the territorial delegate, after marrying a South Carolinian, had adopted a decidedly pro-southern attitude that resulted in a harsh slave code. The southern portion of New Mexico Territory (which was generally referred to as Arizona during that period) was angry about Santa Fe’s seeming indifference to problems in that area. In Tucson, the few federal troops present around the mining areas spiked their cannon, burned their supplies, and departed without offering any resistance to a small militia of Southern sympathizers that then took over. Three hundreds miles east, Mesilla (now a part of Las Cruces, New Mexico) was also a hotbed of Southern sympathy as it had a large population of Anglos originally from Texas. They were aided by major Anglo entrepreneurs in nearby El Paso, who were vehemently pro-South.

Southern Strategy

Military authorities in Texas immediately began to look toward the west, in hopes of capturing additional territory for the newly created Confederacy. This interest was an a continuation of the Southern states’ pre-war efforts

Gadsden Purchase of 1853

to propagate pro-slavery areas in the West any way it could, including promoting a southern railroad route to California that had resulted in the Gadsden Purchase from Mexico in 1853.

As noted by the Houston Telegraph in May of 1862, “…the Federals have us surrounded and utterly shut in by their territory, with the privilege of fighting us off from commerce with the Pacific as well as with Northern Mexico. They confine slave territory within a boundary that will shut us out of ¾ of the underdeveloped territory of the continent adapted to slavery…. We must have and keep…[New Mexico] at all hazards.”

After Texas seceded in January of 1861, it issued a resolution encouraging New Mexico to apply to the Confederacy for admission as a slave state. In Tucson and Mesilla, resolutions were unanimously passed declaring Arizona (at the time the lower half of what were later the states of New Mexico and Arizona) free of Federal rule and repudiating Federal authority. In March of 1861, Arizona issued its own Articles of Secession at Mesilla, stating, “RESOLVED, That geographically and naturally we are bound to the South, and to her we look for protection; and as the Southern States have formed a Confederacy, it is our earnest desire to be attached to that Confederacy as a Territory…”

The South was confident that all of New Mexico and Arizona could be brought under Confederate rule. The territorial governor and military commander were from North Carolina. The territorial secretary was from Mississippi. But it was not a sure thing. Adamantly pro-union miners from Colorado had settled in the territory, and the large Mexican-American population was ambivalent at best about any involvement in what it saw as an Anglo feud.

Early Confrontations

When Texas seceded, the newly appointed military commander of Texas, Gen. Earl Van Dorn, ordered Lt. Colonel John Baylor to take a portion of the new Second Regiment Texas Mounted Rifles west, to re-occupy the abandoned West Texas frontier forts. Baylor was instructed to follow the line of forts into New Mexico if possible and seize any Federal property there. Baylor did as ordered, entering Ft. Bliss (in present day El Paso), and then moving upstream to Mesilla in July of 1861. Mesilla, which presented itself as the capital of the newly formed “Confederate Territory of Arizona” welcomed the Texans with open arms. The Federal commander of nearby Ft. Fillmore attempted to push the Texans out, failed, abandoned the fort, and retreated northward. The Texans pursued, capturing (and later paroling) the entire command. This first Southern military victory emboldened the Confederates to follow-up with a full-blown invasion.

General Sibley

Enter Henry Hopkins Sibley. a federal officer who had resigned his commission at the start of the war. lSibley left his New Mexico post travelling to Richmond, Virginia. There he met with the Confederacy’s new President, Jefferson Davis and convinced him that the South could defeat the few remaining Union troops and bring New Mexico into the Confederacy. He assured Davis that once his Army was raised and provisioned in Texas, it could sustain itself in New Mexico without further need of supplies. Although after the war he claimed that his plan was to take New Mexico, Colorado, southern California, and perhaps even conquer parts of northern Mexico, his stated plan in 1861 was not that far reaching. After convincing Davis of his New Mexico invasion plan, he was commissioned a brigadier general and received the following orders:

SIR: In view of your recent service in New Mexico and knowledge of that country and the people, the President has intrusted you with the important duty of driving the Federal troops from the department, at the same time securing all the arms, supplies and materials of war.

A Call To Arms

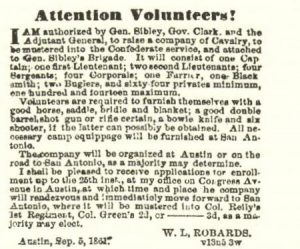

From the Austin State Gazette, September 7, 1861

Sibley headed to Texas and issued a call to arms. Units began to form. DeWitt, Caldwell, Guadalupe, Gonzales, Fayette, Aransas, Parker, Trinity, Austin, and Travis were some of the many counties that contributed troops. Company A, Fourth Regiment, made up of men from Caldwell and Guadalupe counties, was the first company mustered in. It was commanded by William Polk “Gotch” Hardeman, a Guadalupe County farmer who had until recently lived with his family in Caldwell County. The unit was mustered into service at San Antonio on August 28, 1861. Like the folks attending the Prairie Lea meeting nine months later, many of the young men enlisting had surnames recognizable to Caldwell County residents today: Hines, Maney, Nixon, Fentress, Thomas Watts (Luling resident Cal Watts’ great great granduncle), and Beaty, among of others. In all, three infantry regiments plus several artillery batteries were mustered in as one brigade under Sibley’s command.

The approximately 3200 men then received rudimentary military training at San Antonio. On the day of the expedition’s departure, Alexander Gregg, Episcopal Bishop of Texas, blessed the men, and Sibley’s Brigade began its long trek to El Paso. Traveling 600 miles over empty plains and desert with limited water meant the brigade’s units had to stagger their departure so water holes would not be overtaxed. The units trekked through Uvalde, Ft. Clark, San Felipe Springs (now Del Rio), Ft. Lancaster, Ft. Stockton, Van Horn’s Wells, Ft. Quitman, San Elizario, and finally arrived at Ft. Bliss. The three regiments reunited there in late December of 1861 and moved west to join forces with Baylor’s men holding Mesilla and Fort Fillmore.

Sibley then sent some troops toward Tucson and Ft. Yuma further west and detached others to help defend Mesilla and Ft. Bliss. He re-organizing his newly named Army of New Mexico, and launched the main thrust of his invasion with 2600 men supported by 15 artillery pieces. The mood of the army was optimistic at first.

But Sibley’s plan to live off the land by acquiring supplies as he went along proved to be disastrous. Hopes of buying supplies from Mexico evaporated when Mexican merchants in Sonora refused to accept Confederate paper money. This forced the Confederates to forage from the native population. This alienated many New Mexicans, and the many counted-on recruits never materialized. To make matters worse, repeated outbreaks of measles, smallpox, and pneumonia ravaged the men. Despite these setbacks, Sibley and his men remained optimistic that the invasion would not be sorely tested because they did not believe that the Union had any competent commander to challenge them. This perception was wrong.

Colonel Edward Canby

Colonel Edward Canby took control of the New Mexico Territory’s Union forces from their actual commander because he held a well-founded fear that that his superior was a Southern sympathizer. At the time of Sibley’s invasion, Canby had been struggling mightily for several months to recruit volunteers to help keep New Mexico in the Union. He also bolstered defenses at Fort Craig, upriver from Fort Fillmore, and at Fort Union, a huge supply depot in northeastern New Mexico. Many of his recruits were of Hispanic heritage. This enraged the Texans, who were still smarting from the aftermath of the Mier Expedition, a failed invasion into Mexico in 1841 that had led to the execution of many Texan prisoners of war. Adding to Canby’s woes was the fact that many troops still had to be diverted to defend against hostile Apache, Navajo, Kiowa, and Comanche tribes, all of whom were supplied by Comancheros, or Mexicans who traded with the tribes. This dual threat put Canby in a precarious position.

The Battle of Val Verde

Fort Craig was another thirty miles upriver from Fort Fillmore. Canby had managed to recruit over two thousand recruits to supplement Union regulars that he had moved down from Northern New Mexico and Colorado. One regiment was even commanded by the legendary “Kit” Carson.

In early 1862, Sibley’s men moved north against the fort but realized it was too heavily defended to take. Sibley decided to by-pass the fort, hoping to draw the Union forces out for a fight in the open. The Confederates were hampered by bad winter weather in the form of high winds, sleet, blowing sand, and rain. Ill-clad, they were forced to seek shelter in a wasteland of sand dunes and volcanic extrusions. On February 21 Sibley ordered a feint toward the fort. Canby was not tricked, but decided to challenge the Texans on the open field in spite of his many green troops.

He first sent cavalry to the Val Verde ford on the Rio Grande to block the rebels from crossing the icy river. His men beat the Confederates to the ford and fighting broke out. Around noon, Sibley, claiming illness (although possibly very drunk), retired from the field and turned his command over to Colonel Tom Green. Green’s cavalry charged a battery of two Union howitzers but was beaten back. However, the main Southern infantry assault on the Union left overran a six gun battery – re-named “The Valverde Battery” – and the Federal line broke and fled. The Union lost 68 men killed and 160 wounded. The Confederate losses were put at 36, with 150 wounded. Sibley then demanded Fort Craig’s surrender, but Canby refused. J.F. Boesel, a German-American from Austin County, noted in his diary, “On the 21st we met the enemy above, at Val Verde. We Germans stood our ground and fought bravely…We took the enemy in the evening. We got them to running. But our brave Captain, and many other brave men fell.”

It was a victory of sorts, but the Confederates had neither the time or supplies to starve Fort Craig into submission. A large number of horses had been killed in the battle, and many cavalrymen found themselves slogging along as infantry. Low on food, and with freezing weather, Sibley’s men by-passed the fort and continued north toward Socorro. The town, garrisoned by raw New Mexico troops, surrendered without resistance. However, Sibley’s army could not savor its victory because it was again short of supplies. The promise of provisions upstream in Albuquerque beckoned, but Sibley moved slowly, and Canby’s orders ensured that when the Texans finally arrived most of the supplies had been burned. It was a heavy blow to the men, who were ill-prepared for a protracted winter campaign. However, the brigade’s fortunes temporarily reversed when it seized supplies at a depot west of Albuquerque and then stumbled upon twenty-three wagons full of supplies bound for Fort Craig. Sibley had bought enough time to execute the next phase of his invasion.

The Battle of Glorieta Pass

After garrisoning Albuquerque and Santa Fe, Sibley turned toward the huge supply depot at Fort Union, north of present day Las Vegas, New Mexico. If taken, this fort would provide an abundance of badly needed supplies and cut off Canby’s main force at Fort Craig. There was just one problem – the fort’s defenses had been reinforced by Colorado miners eager for a fight.

These reinforcements, called “Pikes Peakers” by the Texans, were commanded by Colonel John P. Slough. Rather than wait to be attacked, he took his men and marched down the Santa Fe Trail in search of Sibley. The federals surprised a small advance party in Apache Canyon and captured seventy-one Confederates. Surprised by Union aggressiveness, the main body of the Confederate force, commanded by Lt. Colonel William Scurry, bivouacked the Army at a place called Johnson’s Ranch to prepare for further attacks. When none came, Scurry’s force of around 1000 men advanced into rugged Glorieta Pass. There they found and attacked the Union force, and after a fierce seven hour battle chased them from the field. It appeared as if the tide was again turning in the Texans’ favor.

However, while the Battle of Glorieta Pass raged, a small Union force under Major John Chivington had stumbled on the lightly-guarded Confederate supply train at Johnson’s Ranch and completely destroyed it. Instead of a glorious advance toward Fort Union, Sibley’s men had no choice but to limp back to Santa Fe and Albuquerque, bereft of food and supplies. Scurry wrote, “The loss of my supplies so crippled me that . . . I was unable to follow up the victory. My men for two days went unfed and blanketless . . . I was compelled to come [to Santa Fe] for something to eat.”

A Bitter Retreat

Sibley sent a plea to Governor Francis Lubbock of Texas, asking for supplies and reinforcements. None were forthcoming. In the meantime, Canby brought 1200 men northward from Fort Craig, intent on joining forces with the men at Fort Union. He attacked Albuquerque, drawing the garrison at Santa Fe out. This allowed Canby’s forces to slip around the Confederate defenses and link up with the a unit from Fort Union. Now with 2400 Union troops united under Canby’s command, Sibley realized his invasion was doomed.

On April 12, 1862 the Army of New Mexico evacuated Albuquerque. The Confederates were hounded south, and as the remnants of his army neared Fort Craig, Sibley acknowledged that his exhausted men would have little or no ammunition to confront its defenders. To bypass the fort and avoid a potential attack by Union troops, the Confederate troops took a grueling, circuitous route through desert mountains. The detour worked, but used up their few remaining supplies and forced them to abandon several artillery pieces. (As an aside, when I was a kid in El Paso, I remember folks with metal detectors climbing in the mountains near Las Cruces, New Mexico, searching for the buried guns – I don’t think anyone had any luck in finding them).

The men vented their anger on Sibley. One stated, “Sibley is heartily despised by every man in the brigade for his want of feeling poor generalship and cowardice. Several [prostitutes] can find room to ride in his wagons while the poor private soldier is thrown out to die on the way. The feeling and expression of the whole brigade is never to come up here again unless mounted and under a different general.”

By the time the brigade arrived in the Mesilla area, only 1800 men were left – the rest had been killed, captured, or left sick or wounded in hospitals along the way.

To complete the defeat, the “California Column” of Union volunteers from that state swept into Tucson and continued east toward El Paso. The Army of New Mexico would have to retreat back to central Texas, or be captured.

After re-provisioning as best it could, Sibley’s brigade broke into smaller units and retraced its steps to San Antonio. Only this time, it was in the middle of the blazing summer heat. The men suffered terribly.

The San Antonio Herald wrote that “A woman who left El Paso on the stage on June 17, 1862 wrote that she had:

…passed the entire first [4th] regiment upon the road at different points. Maj. Hampton was camped at the Muerto….Col. Hardeman was at ….Lympia Canon. The men were suffering terribly from the effects of heat; very many of them are a-foot, and scarcely able to travel from blistered feet. They were subsisting on bread and water, both officers and men; many of them were sick, many ragged, and all hungry; but we did not see a gloomy face – not one! They were all cheerful, for their faces were turned homewards. ‘We are going home!’”

The Prairie Lea meeting was one of many, the result of pleas to send supplies and wagons to help the suffering survivors forced to straggle home across West Texas in the heat of summer. Its wagons met up with a host of troops near the Devil’s River (west of present day Del Rio), and assisted in helping the survivors home.

The Sibley campaign was an unmitigated disaster for the South. Of the 2600 or so men who began the campaign into New Mexico, approximately 1800 returned home. 119 men died on the battlefield or later of wounds, perhaps hundreds died of disease and exposure, and over 500 were captured (although most of these were later paroled). Sibley’s reputation was also a casualty. Recognized as an ineffective leader, a drunkard, and maligned as a coward, he was eventually demoted and relegated to running supply trains for the remainder of the war.

Martin Hall’s “The Confederate Army in New Mexico,” and “Sibley’s New Mexico Campaign” were excellent sources, as were excerpts from our own Plum Creek Almanac. And thanks to Donaly Brice for his assistance.