I met Jack Wilson when Patti and I moved to Lockhart over 35 years ago. I am not sure I have ever met another person who has exhibited such a great enjoyment of life. He is absolutely convinced (and most convincing) that “there is a God,” that but for God’s intervention he would not have survived to tell the stories he recounts, and most of all, and that he has been richly blessed by God. He will not hesitate to tell anyone who will listen that his life has been a whole lot of fun. Sure, there have been some tough times. But nothing has changed Jack Wilson’s belief that it has been one heck of a ride.

Jack was the youngest child of Clarrissa (Dennis) and James Floyd Wilson. His older sisters were Claudia Roberta, Martha Mae, and Julia Clarrissa. Jack’s mom was of a pioneer family from Moran, in Shackleford County, and his father was from Orange, in far East Texas. Jack’s mother and father met and married in Carrizo Springs in 1911. By 1917, the Wilson family had moved to Lockhart. James was an auto mechanic, and a gifted one, all his life. He worked for Citizens Autos in 1917, and later for Lockhart Motor Company. Jack was born in Lockhart in 1922. His nickname – Jack – was given him by a coach in high school who didn’t like his given name. He has gone by Forrest or Jack ever since.

Jack’s childhood was by his account a very happy one. “I really had a wonderful family,” he says. Sadly, in 1936 his mother died of what was described as pellagra. Normally describing a niacin deficiency, it probably was an indicator of a more serious disorder. Regardless, Clarrissa, who was deeply loved and admired, was gone. Later, James remarried to Esther Chapman. She was a stern but loving step-mom. “We were poor as hell,” Jack recalls. James Wilson worked six days a week, often twelve hours a day, to put food on the family table. But Sunday was the Lord’s Day, and the Wilson family was in very regular attendance at Lockhart’s First Presbyterian Church.

Jack attended Lockhart schools. His chums included Bobby Balser, Herb Reid, and Mack Connolly. He played football in high school. “We weren’t all that good,” Jack says, “but we sure had a lot of fun trying.” He had a burning desire to attend Texas A&M, but in June of 1941 the United States was still in the throes of the Depression. Fortunately, his sister Claudia had married a Former Student who was a successful engineer, and the couple gave Jack $1000. “I knew that would get me through an entire year,” Jack recalls. “After that I figured I’d find a way to finish up.” A fish in the Corps of Cadets, he was assigned to G Company – Infantry, in the new Quadrangle near Duncan Dining Hall (its twelve dormitories are still Corps housing). Mack Connolly’s mother drove Jack and Mack to college. They were to graduate with the Class of 1945. Neither made it. Mack would eventually drop out, become an artillery officer, and be killed in combat in Germany three weeks before the end of the war. Jack ran out of money after the first year, hitched a ride to Waco, and went to work helping build Waco Army Air Field (later James Connolly Air Force Base). He received his draft notice while working there, so decided he wanted to be an Army Air Corps pilot. First he had to pass the written test – and he didn’t! He heard the Naval Air Corps written test was easier, so he took that, passing with a 90. The grueling physical exam was a breeze to a young man who’d known nothing but hard work. When he found he was officially a Naval Aviation Cadet, ‘I thought I had gone to heaven,” he recalls. “I was in the naval air corps, and I had never been in an airplane!”

Things just kept getting better. Jack was inducted and sent to Schreiner Institute (now Schreiner University) in Kerrville where he took ground school classes, and soloed in a Piper Cub after 8 hours of dual instruction. From there, he entrained for California. He and other air cadets on the train thought the worst when the train passed along the misery of Ft. Ord. Once again, Jack’s guardian angel was with him. The cadets wound up housed in one of the most luxurious hotels of its time. Hotel Del Monte, in Monterey, California had been requisitioned by the Navy. Instead of tents, the aviation cadets were ensconced in fancy hotel rooms. “The place even had a heated swimming pool.” Granted, there was a lot of spit and polish, military routine, and schooling, but mostly “they were trying to make gentlemen out of us,” he remembers. “And it was near the Pebble Beach Golf Course. It was high kicking.”

Hutchinson, Kansas was no Monterey, but here, Jack learned to fly the Stearman PT-17 “Kaydet” biplane. Then it was south to Pensacola, Florida for advanced training in a Vultee “Vibrator.” At Pensacola, he transitioned into the SNJ or AT-6 “Texan.” While at Naval Air Station Green Cove Springs, he was given a choice of staying in naval aviation, or transferring to the US Marines. Jack joined the US Marines. “I always wanted to be a Marine,” he says. “They were the toughest.” And besides, the transition might get him into the war faster.

He was then introduced to America’s early Marine and aircraft carrier-based workhorse, the Grumman F4F Wildcat. It was a tough bird, but could be tricky to fly. 27 cranks were required to retract the landing gear. In addition, the landing gear was narrow, which could give a pilot nightmares if there were crosswinds – it was easy to ground loop. However, with 1200 horsepower, it was a joy for a young man wanting to fly a mean combat aircraft.

While manuever flying with Wildcats over Pensacola, his four plane formation was “attacked” by Army Air Force P-47s. “They came screaming through us, and the war was on.” The chase plane instructor’s screamed radio messages to resume the formation were gleefully ignored, as mock dog fights erupted. Jack laughs as he recalls that “this was the closest I got to the war!” Another time, his flight took off for training from one of the auxiliary fields near Pensacola. When they landed, he saw all sorts of reporters and photographers standing around, waiting for several groups of pilots to enter the hangars. “I thought they wanted to interview me,” he says. Not hardly. They clustered around another tall Marine. “Who is that?” he asked his buddies. “That’s Ted Williams.” Jack asked, “Who is Ted Williams?” The response: “You dumb ——, he’s the greatest baseball player in history.” Later, Jack and his buddies got to meet the Red Sox hero. Turning down a chance to fly night fighters (“I hated night flying”) he jumped at an assignment to a training squadron in Cherry Point, North Carolina.

Jack transitioned to one of the greatest fighters of World War II – the Vought F4U Corsair. This gull-winged fighter was (and is) a thing of beauty. Although the Navy flew it off carriers in World War II and in Korea, its true home was with the Marine Corps. Powered by a 2000 horsepower Pratt and Whitney R2800 Double Wasp radial engine, it had an outstanding career as a combat aircraft. If there is any doubt as to Jack’s love for this aircraft, ask to see the ring he wears, and which he and daughter Stephanie designed – the outline of the F4U is a prominent feature.

He and other pilot trainees were hot to get into the war. But no matter how hard he tried, something would always derail his attempts. While training on the Corsair, he received his next set of orders – not overseas, but to Floyd Bennett Field in New York. For the next 15 months, Jack flew single engine aircraft – mostly fighters and torpedo bombers – from factories to various airfields all over the United States. He felt God’s saving grace on many occasions. One in particular: horrible weather at Jackson, Mississippi had all aircraft grounded until 4 p.m. when the tower claimed the weather was clearing, and gave Jack clearance for Ft. Worth. He had allowed a sailor to hitch a ride in the belly of the torpedo bomber he was ferrying. As he climbed into the clouds, lightning and turbulence increased. With nightfall approaching and flying conditions incredibly dangerous, he and another aircraft were dead reckoning, without radio contact. It looked like the end. “I knew I had to get that plane on the ground, but I had no idea where I was,” he says. “I looked down, and there was a tiny part in the clouds, so I spun down and darned if I hadn’t shown up in Ft. Worth! God had literally saved my life.” After landing safely, the sailor emerged badly shaken from the belly of the plane and said he would “find another ride.” He also stole Jack’s expensive Parker pen!

The war ended, and Jack was transferred to Quantico, Virginia for advanced officer classes. One day, he glanced down at the newspaper’s daily horoscope. “I NEVER read those damned things,” he says. But this day he did. The horoscope said, “You will take a long trip over water in three days.” Coincidence? Of course, but the following morning he got orders sending him to Asia. From San Francisco, he boarded a “slow boat to China.” Traveling at 8 knots per hour, it took 30 days to arrive at the Chinese mainland, where he became part of Operation Beleaguer. Thousands of young Americans had trained intensively for the invasion of Japan. When Japan surrendered, there were over 500,000 Japanese and Korean troops in Northern China needing repatriating. Also, the US had, somewhat reluctantly provided support to the Nationalists in the fight against Japan, as well as in the decade long civil war against Mao Zedong’s communists. American Marines were landed to maintain some sort of stability, to fill the vacuum created by the surrender, and to allow the US recognized Nationalist Chinese to re-occupy many cities. American marines landing at Tientsin (Tianjin) were met with a tumultuous welcome. The First Marine Air Wing took over airfields in and around Peiping (Beijing). The early euphoria exhibited by most Chinese masked a very unsettled landscape of warring parties. It quickly became obvious that warlords, communists, Nationalists and others were going to make the American presence on the mainland of China an increasingly dangerous mission. In the words of Marine Brigadier General R.G. Owens, Jr.:

On both political and moral grounds, it was impossible for the United States to take a decisive military role in another nation’s civil war, and the average Marine on postwar duty in China found himself an uneasy spectator or sometimes an unwilling participant in a war which he little understood and could not prevent. A steady procession of “incidents” involving Marine guards and raiding Communists continued until the last Marine cleared Tsingtao in the spring of 1949.

Jack’s involvement was mercifully short. In unarmed F4U Corsairs, he and others flew reconnaissance missions from dusty, hot airfields. “All I remember was that there were a hell of a lot of communists swarming all over the hills.” Within two months, he was ordered home. Thankfully, the return trip to the USA was on a C-54 transport. Shortly before leaving, he got into a poker game with his last twenty dollars, walking away with a large pot. “I bought Chinese silks for my step-mother and all my sisters,” he told me. Arriving in San Francisco, he entrained for San Diego and discharge. Once there he pleaded with the Marines to allow him to stay in. He loved his military flying experience and wanted to make a career of it. “Hell no,” he was told. “We’ve got thousands [of young pilots] like you. You can’t stay in.” So he didn’t. Jack returned to Lockhart and went to work for Stripling Blake Lumber Company. Jack married Fayrene Bolton in 1949. She was a West Texas girl who had attended West Texas State, and landed a job with a federal old age pension office in Lockhart. They would have two children, Stephen Floyd and Stephanie Ann (Riggin).

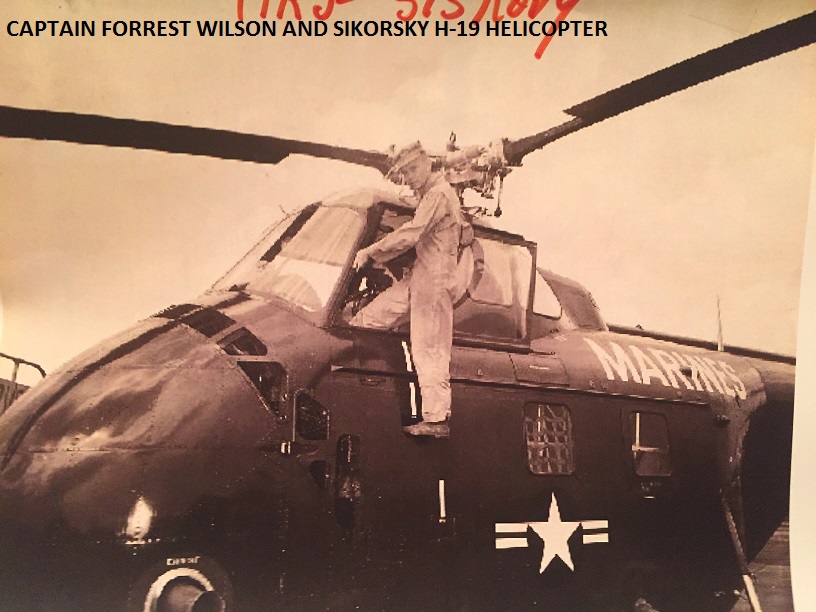

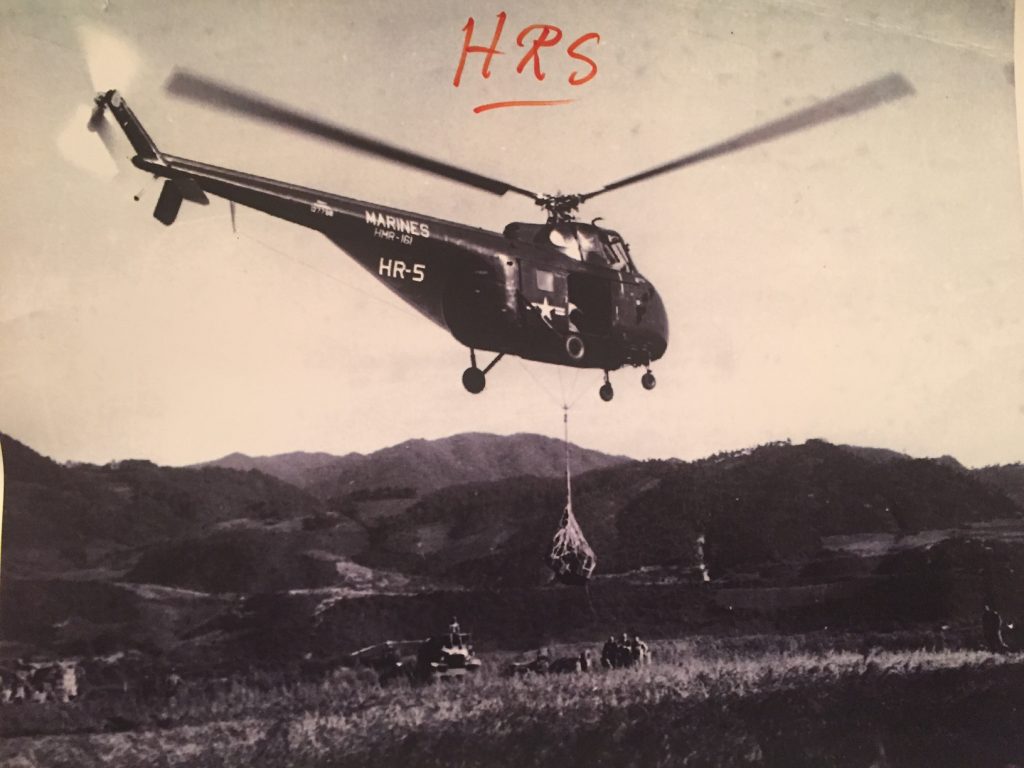

Soon after they married, Jack was called back to active service because of the outbreak of war in Korea. He was given the opportunity to learn another type of aviation skill – flying helicopters. After some initial uneasiness, he learned the intricacies of rotor flying near Santa Ana, California. In 1952, Fayrene gave birth to their son Stephen – now an innovative and successful architect. Jack spent a peripatetic two years on active duty. Three things stand out of his time:

He got to meet Igor Sikorsky, the Russian-American designer of the first viable American helicopter. He recalls this genius as a person who had a photographic memory, and who wasn’t’ afraid to ask aviators what could be done to make his designs better.

His “overseas” duty – again, the Good Lord kept him from harm’s way – as rather than the dangers of Korea, he spent several months in Hawaii, assisting in training and military exercises.

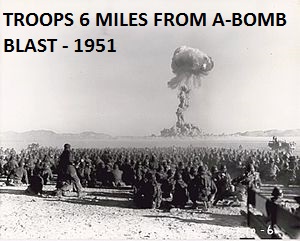

Finally, he recalls participation in an atomic bomb test. Beginning in early 1951, the United States detonated hundreds of nuclear weapons in the Nevada desert, often within eyesight and seismic shock range of Las Vegas. It is hard to believe now, but in some early tests, American soldiers were used as guinea pigs to check ‘survivability.’ In several, helicopters were used to transport troops into nearby areas shortly after detonations. He was sitting as co-pilot in a helicopter when a ‘low yield’ atomic bomb detonated some 15 miles away, before he could turn to avoid looking at it (which he shouldn’t have been doing anyway) – or as he says, “that damned thing went off at the count of three [instead of at the zero count].” Temporarily blinded, he speaks in awe of the brilliance of the explosion that seemed “far brighter than the sun.”

Jack was finally discharged in 1954. The Marine Corps decided this time that it wanted him to make a career of it. He refused, saying, “I wanted to stay in after the last war and you wouldn’t let me. Now I’ve got a family, so to heck with that.” Daughter Stephanie came along in 1955.

In 1970, Jack and George Cardwell purchased Stripling Blake’s Lockhart operation. George retired in1980, and Jack bought out his partner. This thriving business, now Wilson Riggin Lumber Company, is owned and operated by his daughter and son-in-law Mark Riggin. They have followed Jack’s example, giving back to their community in countless ways.

Among many other achievements, Jack has been a Boy Scout scoutmaster, avid fisherman and golfer, and remains a devout Presbyterian. He helped start the “Fun-tier Days” which is now Lockhart’s annual Chisholm Trail Roundup. In 1977, he was honored as Lockhart’s Most Worthy Citizen. His artistic, whimsical and humorous flair helped create the often hilariously and ingeniously designed Chisholm Trail parade floats for which the lumber company is famous.

His beloved Fayrene passed away twenty eight years ago. A few years later, Jack married Kathy Harrell. He has been doubly blessed by the two beautiful women he has been privileged to be with. He lives in a house that he helped design (and which son Steve helped adapt) in 1970s on Merritt Drive. Jack’s days continue to be busy. He spends most of each day at the nursing home with his wife Cathy, taking breaks to ensure Mark and Stephanie are properly running the lumber company. Until very recently, he ensured the esperanzas and other flowers in First Presbyterian’s planters were the envy of anyone with a garden.

As he says, “It’s been a heck of a ride.”

POSTSCRIPT: I wrote this story in July of 2016. My friend Jack Wilson died on June 6, 2019 at the age of 97. I think he would have approved of his death coming on the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings. He was a hell of an hombre. TAB