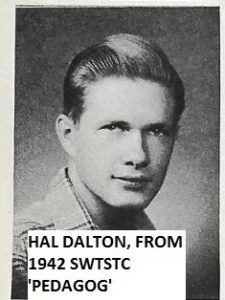

HAL WILLIAM DALTON

by Todd Blomerth

Hal William Dalton was the middle son of William Ewen Dalton and Delta (Martin) Dalton. He was born on February 20, 1923 in Hays County, Texas. His older brother Wesley was six years his senior. Younger brother Robert, or Bobbie, was born in 1932. Hal’s father, Ewen, began married life as a farmer in Hays County, and then changed careers. For most of Hal’s life his father was an automobile salesman. At some time between 1930 and 1935, the family moved to Luling. Shortly before Hal entered high school the family relocated to Lockhart, living at 623 Cibolo Street.

Hal was active in the Lockhart High School Band, and was at one time an assistant drum major. According to Harry Hilgers, during the Depression, few could afford to buy band uniforms, so cast-off University of Texas Longhorn Band uniforms were obtained, and band mothers would dye them, changing the color from orange to maroon. The band mothers would then make the trousers. Caps were also from the Longhorn Band, which were also dyed appropriately. Hal’s senior year he, along with Andy Hinton, Winifred Adams, Vera Riddle, Opal Shinn, Dorothy Nell Williams, Corbett Halsell, Branch Lipscomb, and Hollis Raymond, starred in a play at the Adams gym – “Professor, How Could You?”

Hal graduated from Lockhart High School in May of 1940 and  enrolled in Southwest Texas State Teachers College (now Texas State University). He attended for two years, and served on the Student Council. He was also a member of the Harris-Blair Literary Society. Like many others, he did not finish school, enlisting in the Army Air Forces in 1942.

enrolled in Southwest Texas State Teachers College (now Texas State University). He attended for two years, and served on the Student Council. He was also a member of the Harris-Blair Literary Society. Like many others, he did not finish school, enlisting in the Army Air Forces in 1942.

Hal graduated from Bombardier School at Kirtland Airfield in Albuquerque, New Mexico, training on AT-11s and B-18As. The AT-11 was built by Beech. It was a twin-engine trainer and personnel transport that after the War became a popular business aircraft. The B-18 “Bolo” was developed in the 1930s as a medium bomber. By the onset of the War, its deficiencies were obvious – inadequate bomb load capacity and armament, and underpowered engines. It was soon relegated to anti-submarine patrols and training missions.

Hal was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant and received his bombardier’s wings. He then went overseas in May of 1944, completing thirty-three combat missions in the European Theater of Operations.

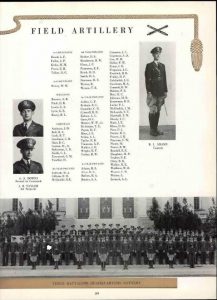

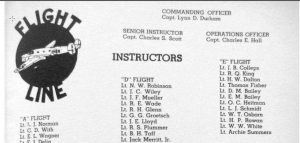

By June of 1945, the Dalton family perhaps thought it would remain intact despite others’ losses in World War II. Bobbie was too young to serve in World War II. Wesley had served with Dr. Joe Coopwood’s Medical Detachment of the 143rd Infantry Regiment, He had been wounded by artillery shrapnel in Italy, but recovered. Returning to the States, Hal was assigned as bombardier instructor at San Angelo Army Air Field. The school’s class book, “On Course!”  shows Hal was an instructor for student Flight “E” of Class 45-15B. The war in Europe was over and he was training others to be bombardiers in the continuing fight against Japan. His assignment was a challenging but pleasant change from the high-risk operations of aerial bombardments. One thing was certain – after what he had lived through, he was not supposed to lose his life in the continental United States. But he did, and needlessly.

shows Hal was an instructor for student Flight “E” of Class 45-15B. The war in Europe was over and he was training others to be bombardiers in the continuing fight against Japan. His assignment was a challenging but pleasant change from the high-risk operations of aerial bombardments. One thing was certain – after what he had lived through, he was not supposed to lose his life in the continental United States. But he did, and needlessly.

Bobbie had spent part of the summer of 1945 with his big brother, Hal. Mr. and Mrs. Dalton, by now living at 4120 Tennyson Street in Houston, left Houston early on Saturday, June 30, 1945, driving to San Angelo to pick up Bobbie. Shortly after leaving, a telegram arrived at their home. Another family member saw its contents, and telephoned Wesley, now living in Lockhart. Wesley parked on the side of the highway he knew his parents would be taking to San Angelo and flagged them down as they approached. He broke the news that Hal had been killed the night before in a training accident.

At 9:12 p.m., Central War Time, a Beechcraft Model 18 (the  military nomenclature was AT-11A “Kansan”), aircraft number 43-10417, took off from San Angelo Army Airfield. There were three men on board: 2nd Lt. Thomas E. Nageotte – pilot; 1st Lt. J.B. Colleps – bombardier instructor; and 1st Lt. Hal Dalton – bombardier instructor. The flight was for bombardier instructor proficiency training – in other words, Lieutenants Colleps and Dalton were maintaining that their own skill levels.

military nomenclature was AT-11A “Kansan”), aircraft number 43-10417, took off from San Angelo Army Airfield. There were three men on board: 2nd Lt. Thomas E. Nageotte – pilot; 1st Lt. J.B. Colleps – bombardier instructor; and 1st Lt. Hal Dalton – bombardier instructor. The flight was for bombardier instructor proficiency training – in other words, Lieutenants Colleps and Dalton were maintaining that their own skill levels.

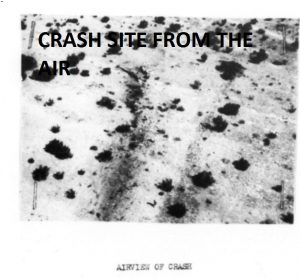

The AT-11A, powered with two Pratt and Whitney R-985 engines, rated at 450 horsepower each, crashed near Christoval, killing all three occupants. Several miles from the airbase it struck the arid ground at a shallow descent, bounced once, twice, and on the third strike exploded. Very little of the aircraft was left intact. The resulting investigation gave no clear explanation for what had happened. Report of Major Accident Number 45-6-29-21 noted:

The accident occurred at about the part of a bombing mission where the last bombardier is completing the 12 C Report on bombs dropped and the pilot is losing altitude for entrance into the traffic pattern at the home base. It is possible that the reflection of the bombardier’s nose light on dirty glass might have blinded the pilot enough to cause confusion and error.

The investigators also surmised the possibility of an air lock, as the one hour and eighteen minute flight would have emptied the main fuel tank. “With possible air lock in fuel system, [and the plane descending from the practice bombing run altitude] the pilot may have placed his entire attention inside the cockpit long enough for the accident to occur.” In other words, there was no clear explanation for the three deaths. The aircraft simply flew into the ground, plowing up mesquite and cactus, before disintegrating.

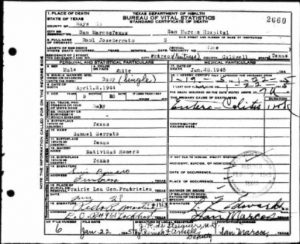

A good friend, Lt. C.D. With accompanied Hal’s body home. Funeral services were held at Rogers-Pennington Funeral Home in San Marcos on July 2, 1945. Dean H.E. Speck, the men’s dean at SWTSTC spoke glowingly of Hal. A letter from Reverend C.E. Bludworth, pastor at First Methodist Church at San Angelo, and former pastor at First Methodist in Lockhart, was read. Reverend Bludworth knew Hal as a boy in Lockhart, and became re-acquainted with him when Hal began attending church at Rev. Bludworth’s church in San Angelo. Pall bearers included Joe Lipscomb, C.E. Royal, Alton Williams, and Jack Hoffman.

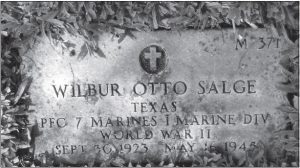

1st Lt. Hal Dalton did not reach his 23rd birthday.