LIEUTENANT (j.g.) PHILIP WALES, USNR CIRCA 1943

LIEUTENANT (j.g.) PHILIP WALES, USNR CIRCA 1943

I want to tell you a story about someone many of us have the privilege of knowing. Fresh out of medical school, in 1944 he was sent as a young military officer to the Pacific Theater. His wartime service as a Navy physician exposed him to some of the most interesting experiences of his life – and some of the most tragic. He carries those memories with him today, at the age of 95. A venerable patriarch, well loved and deeply admired, he served our country in World War II. Not as warrior, but as a healer.

I had the privilege of visiting with the Dr. Philip Wales in his home last month. He was kind enough to share with me some stories of life in the military. His memory is flawless. Hopefully, my historical research adequately complements it.

Philip Wales was born in Florence, Williamson County, Texas on June 19, 1919 to Prosper and Ruth Wales. His sister Lois would come along a few years later. His father was the president of Florence’s Union State Bank. Times were tough in rural Texas. Being financially ‘well off’ in rural Texas in the 1920s and 1930s was a relative term. He is very proud of his father’s legacy as a man who understood the struggles to survive during the Depression and who was willing to lend money to farmers for crops and seed. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered all banks closed for several days to prevent a run on their cash assets in what was called the Bank Holiday. It staved off what would have been a national disaster. He still remembers those times and how, because of Prosper’s stewardship, the Union State Bank survived

After graduating from high school at the age of sixteen, Dr. Wales enrolled in Abilene Christian College, intent on becoming a doctor. Upon graduation, he applied to the University of Texas School of Medicine in Galveston (UTMB). Despite excellent grades, acceptance to medical school was not guaranteed. There were only two medical schools in Texas in those days – UTMB and Baylor – and each took classes of only 100 students. With America’s entry into World War II almost assured, there were many eager to attend medical school, and undergraduates had to compete with graduate students and others with advanced training for the few spaces available. UTMB received over 1500 applications. Dr. Wales’ was one of the 100 chosen

Wanting to serve in the United States Naval Reserve, Dr. Wales enlisted while at Abilene Christian and applied for an appointment as an officer. During medical school, he carried the rank of an ensign. Upon graduation from medical school in 1943 (in an accelerated three year program) he was promoted to Lieutenant (JG) in a ceremony at Corpus Christ Naval Air Station. He excelled in school, and was a member of two fraternities, Phi Chi and Theta Kappa Psi. He also received additional training in anesthesiology.

Dr. Wales was sent to San Diego for a modified basic training for medical officers. Bachelor officers’ quarters were scarce so the government requisitioned the famous Hotel Del Coronado. One half of it provided housing for naval officers in training or awaiting transfer to other assignments. The other half was reserved as temporary quarters for families of naval personnel already shipped out. From San Diego, Dr. Wales was ordered to Point Hueneme, near Oxnard, California. Soon he was enroute to Hawaii on a convoy of troopships escorted by a cruiser and half a dozen destroyers. He remembers that the scars of the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor were still very apparent as they sailed into port. Salvage operations were still ongoing. The USS Arizona entombed the bodies of 1100 sailors. It was a solemn introduction to the realities of war.

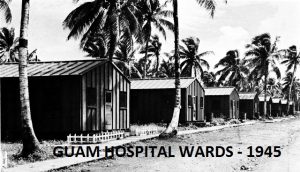

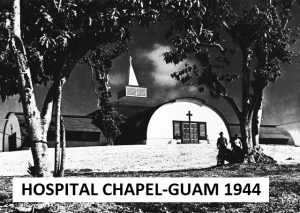

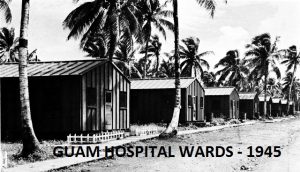

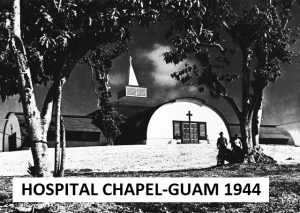

Although eventually to be based at the Navy’s huge anchorage at Ulithi, Dr. Wales and other medical personnel were temporarily assigned to medical facilities on the island of Guam. An American possession until taken by the Japanese in 1941, it had been retaken by the Marines in July and August of 1944. Although technically ‘secured,’ fighting was still going on in the hills when he arrived. Doctor Wales gives much credit to the Seabees – construction units – that were unafraid to go anywhere to build runways and facilities. They and Army engineers proved their worth in Guam. After the retaking of Guam, hospital construction began in September of 1944. There were occasional light moments. Dr. Wales tells of starving Japanese who would sneak down from the hills in stolen American uniforms and attempt to line up for chow. They would be quickly nabbed and put in the stockade – and then fed.

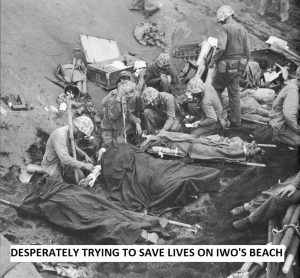

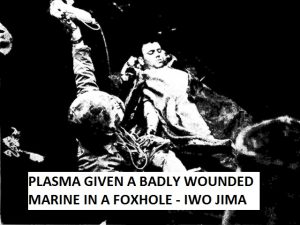

By February of 1945, about 9000 beds were in service at three Navy hospital and two Army hospitals. They would be needed. Dr. Wales (who was, as one might expect, nicknamed “Tex”) became part of the huge contingency of medical personnel preparing to treat those wounded in the expected attack on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima. After the bloody horrors of Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Tarawa and most recently, Peleliu, planners knew very well what to expect. Medical support was better than at any time in the past.

The island of Iwo Jima was honeycombed with miles of tunnels and thousands of hidden gun emplacements and covered with interlocking fields of fire. Japan had demonstrated repeatedly its contempt for the conventional understanding of warfare – in China, Manchuria, Indo-China, Philippines, and on Pacific Islands. Japan’s warriors had no intention of

The island of Iwo Jima was honeycombed with miles of tunnels and thousands of hidden gun emplacements and covered with interlocking fields of fire. Japan had demonstrated repeatedly its contempt for the conventional understanding of warfare – in China, Manchuria, Indo-China, Philippines, and on Pacific Islands. Japan’s warriors had no intention of  surrendering. There was absolutely no way to root out concealed killers moving back and forth from hidden bunker to hidden bunker. Ultimately, there were more total casualties to Marines and Navy at Iwo than to the Japanese. Almost to

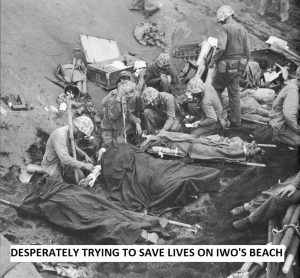

surrendering. There was absolutely no way to root out concealed killers moving back and forth from hidden bunker to hidden bunker. Ultimately, there were more total casualties to Marines and Navy at Iwo than to the Japanese. Almost to  a man, the subjugation of the island required to extermination of the garrison of over 20,000 men. Over 800 corpsmen, stretcher bearers and doctors were killed and wounded by the defenders. There was no understanding of, or agreement with, the accords for ‘humane warfare’ (as if such a thing exists). According to a subsequent analysis by military historian Dr. Norman Cooper, “Nearly seven hundred Americans gave their lives for every square mile. For every plot of ground the size of a football field, an average of more than one American and five Japanese were killed and five Americans wounded.” Napalm, white phosphorus and flamethrowers were often the only weapons that were effective.

a man, the subjugation of the island required to extermination of the garrison of over 20,000 men. Over 800 corpsmen, stretcher bearers and doctors were killed and wounded by the defenders. There was no understanding of, or agreement with, the accords for ‘humane warfare’ (as if such a thing exists). According to a subsequent analysis by military historian Dr. Norman Cooper, “Nearly seven hundred Americans gave their lives for every square mile. For every plot of ground the size of a football field, an average of more than one American and five Japanese were killed and five Americans wounded.” Napalm, white phosphorus and flamethrowers were often the only weapons that were effective.

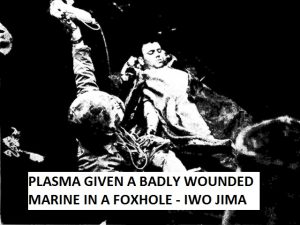

Huge hospital ships stood offshore at Iwo Jima, filling their wards with the wounded and dying. Physicians stabilized the badly wounded, and the ships, with names like Bountiful, Samaritan, and Solace, made round trips to Guam to offload the damaged men. Hospital ships had surgical suites. Amputations were common. The medical staffs worked overtime to deal with wounds and injuries from mines, bullets and artillery. Americans too were burned – by the enemy’s use of similar weapons, by friendly fire, bombs falling to close, and accidents. The horrors of burn victims were agonizing for  everyone witnessing them.

everyone witnessing them.

With a specialty in anesthesiology, Dr. Wales’ expertise was an absolute necessity. The wounded that still dwell in Dr. Wales’ mind were the young Marines suffering from burns. They were treated in the ward manned by Dr. Wales and others. He saw many young Marines who were going to die. It was just a matter of when. Heroic measures were taken to save them. Skin grafts were made when possible. But it was often not enough. Dr. Wales reports that if there were deep third degree burns covering 30% or more of a man’s body, he would die. If his lungs had been seared, he would die. In those instances, the only care was palliative. All the medical staff could do was hydrate, provide comfort, and give morphine to ease the pain. Less that 50% of the Marines treated in his burn ward survived. “There was nothing we could do,” he said, “except try to ease the suffering.”

Dr. Wales won’t spend too much time on the sadness of seeing young men die and suffer, other than to say that it haunted him. It also gave him experience and training that he could never have duplicated in civilian life. I have no doubt that it made him a much better doctor, and a more empathetic one. How did he handle the tragedy of so many young men dying or forever horribly mutilated? “I didn’t,” he said. He was deeply saddened and depressed, and would return to the wards at night. Like every other American, he was afraid – afraid of what would happen to hundreds of thousands of young American boys when the invasion of the Japanese homelands occurred. Indoctrination of all personnel was given on what to expect – a well armed and fanatic populace where every man, woman and child could be expected to give his or her life for the emperor, and where no quarter was to be given nor expected. In short, a bloodbath of epic proportions. Its looming reality was a very real presence to every other American in uniform in the Pacific (and most of those in Europe who were to be rotated to the Pacific for the invasion).

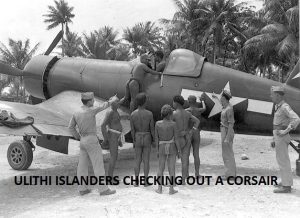

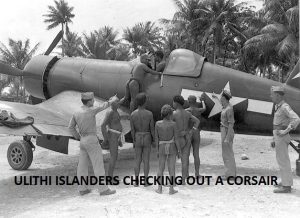

Most of Dr. Wales’ active duty time was spent at the huge naval facility on Ulithi. The westernmost of the Caroline Islands, the Ulithi Atoll would become one of America’s best kept secret weapons. Its huge and deep waters, surrounded by forty small islands at one time provided anchorage to over 700 ships of all kinds. Deserted by the Japanese in early 1944, it was taken over by the Americans that August. Almost overnight this distant and nearly empty place was transformed – floating dry docks big enough to dry lift battleships, tenders, mess halls, supply depots, and ice cream barges.

There was much medicine to be practiced, as Ulithi had large medical facilities as well. Nevertheless, there was also time for occasional frivolity and laughter. Being low man on the totem pole so to speak, Dr. Wales was Ulithi’s sanitation and recreation officer along with his medical duties. He still chuckles at the reaction given him when he shut down the Marines’ galley at their airbase. The commanding general got mad, but there was nothing he could do about it, so the Marines cleaned the place up and it got reopened.

Different islands were fortified. Mogmog became an R&R place where men could drink a few (warm) beers.

The nearby Yap archipelago had been surrounded and the Japanese force of nearly 6000 isolated. The Americans did run continuous bombing and strafing runs on Yap – and often with dire consequences to the attackers. Many were shot down.

The islanders living on the scattered islets of Ulithi were moved to Fedraey, one of the atoll’s small islands. The islanders took it stride, and the Americans provided food and tent housing. Dr. Wales and other medical personnel would periodically take a small boat to the island to provide medical care. “They were a handsome and friendly people,” he said. The chief was paralyzed from polio, but had cadged a Japanese motorized ammunition cart which he drove around. Dr. Wales got along with him famously, in part because he brought the chief cartons of American cigarettes. He would sew up gashed heads and fix broken arms. The children enjoyed the strangers, and Dr. Wales often recruited some of the children to help him distribute the vitamins.

Dr. Wales came back to mainland United States in December of 1945 on an aircraft carrier along with 4000 soldiers, sailors and marines housed in the hangar deck. The ship docked in Seattle. Shivering in the winter cold, he walked into town and bought two pairs of long handled underwear. He eventually took a train to Long Beach, California, and then onto Houston. Back in Texas, Dr. Wales continued as a physician in the United States Navy Reserve, retiring as a captain (naval equivalent of a colonel) after thirty years of service.

Returning from the war, he took a surgical residency in San Antonio, and later in Austin. He met Dr. Riley Ross in Austin. Riley introduced Dr. Wales to his brother, Dr. Abner Ross. As partners, Drs. Dubois, Ross and Dr. Wales opened the Lockhart Medical Center. Struck down by appendicitis in the early 1950s, he was cared for by a beautiful young nurse named Elizabeth Schneider. Wisely, he sought her hand in marriage. They married at First Baptist Church on May 1, 1952. Hundreds of Caldwell County citizens were delivered by Dr. Wales. Hundreds owe their lives to his skills as a physician and obstetrician.

The next time you see Dr. Wales, don’t forget to thank him for the healing and comfort he provided to so many American men grievously wounded in battle.