By Todd A. Blomerth

Tinker Hendricks in 1943 as an aircrew student

It is July of 1944. You are the parents of six sons. The oldest five are in the Armed Forces of the United States. Four are overseas in combat zone assignments. A fifth will soon be there. The only son left at home, Michael is a young boy. You proudly display five Blue Stars in your front window. You’ve seen Gold Stars appear in your neighbors’ windows and seen the grieving parents attempt to deal with the death of a child. Every day the war drags on, the chances become greater that you too will lose a child to war.

Minor, your oldest, is with the 36th Infantry (“Texas”) Division which has been badly bloodied in Italy. Arthur (“Jack”) witnessed the attack on Pearl Harbor and is with the Army Air Force somewhere in the Pacific Theater. Risdon (“Buck”) is serving as a Military Policeman, somewhere in Italy. Douglas (“Tinker””) is a crewman on a B17 bomber somewhere in Europe. Harvey (“Salty”) has recently joined the Navy as a 17-year-old and will soon see combat as a sailor in the Pacific.

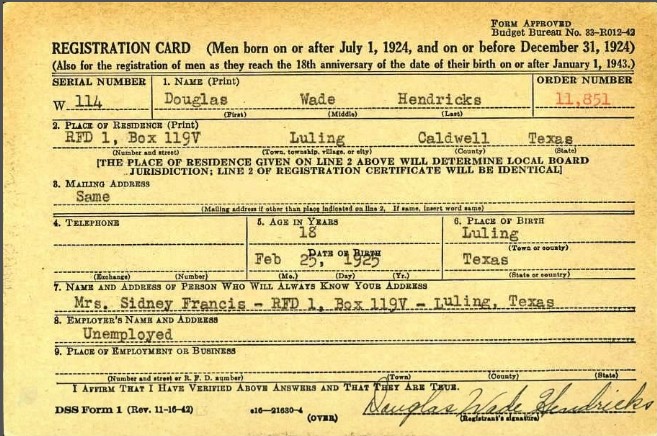

Douglas Tinker’s Draft Registration Card

The daily life of Risdon Hendricks and his wife Sidney Frances (Pierce) Hendricks must have at times been excruciating. Thankfully, their boys all came home. It nearly wasn’t so.

Tinker Hendricks enlisted in the Army Air Force right after his eighteenth birthday. Soon he was at Sheppard Army Field, outside of Wichita Falls, Texas beginning his training as a bomber crew member. He completed his training as B17 aircrew man at Avon Park Army Air Field. The B17, dubbed “Flying Fortress,” was a high altitude, four-engine, heavy strategic bomber. The crew consisted of ten men: flight commander, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, radio operator, flight engineer and upper turret gunner, two waist gunners, tail gunner and ball-turret gunner. By the summer of 1943, the “G” model was replacing older models. The aircraft bristled with firepower, having thirteen heavy machineguns. Despite its name, unless escorted to the target by fighters such as the P51 Mustang, it was no match against enemy air attacks. Even with fighter support, anti-aircraft or “flak” guns remained deadly.

1st Lt. Haas and his crew – Tinker is lower right

On May 10, 1944, the crew members of a brand-new B17-G received their orders for overseas. The ten men, four officers and six sergeants, were to proceed from Grenier Field, New Hampshire to England via the North Atlantic Route. And so began Sergeant Douglas W. “Tinker” Hendricks’ combat tour as a waist gunner on a Flying Fortress.

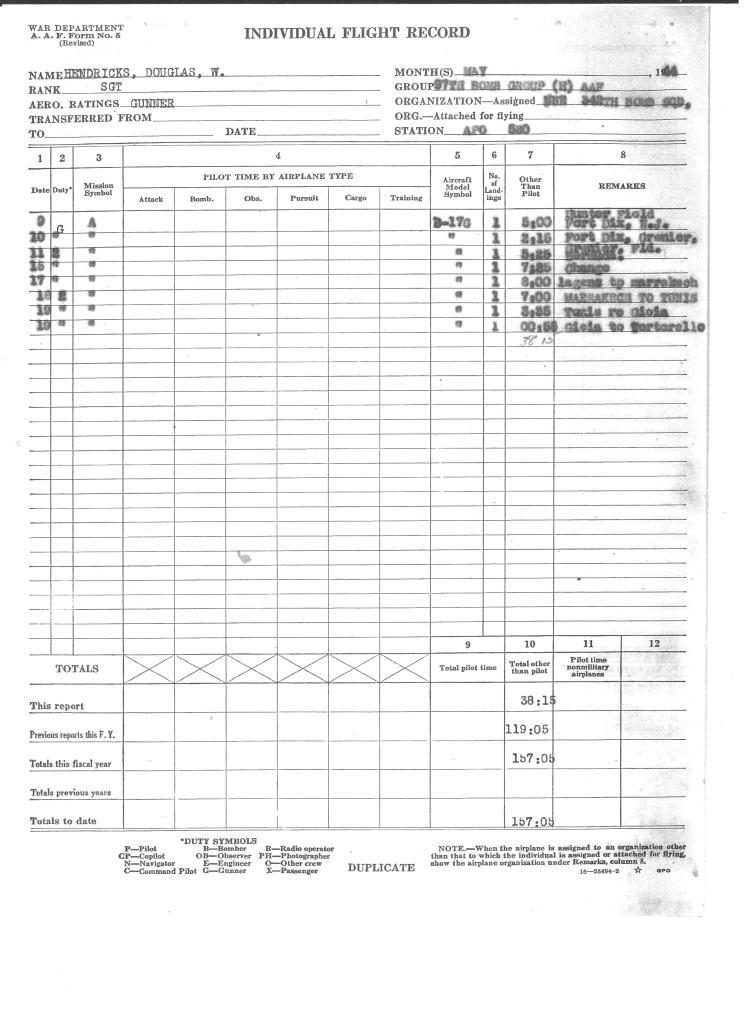

Tinker later wrote: We were assigned to a new B17G at Hunter Field, Georgia…From Hunter Field we flew to Fort Dix NJ to Grenier, to Bermuda to Marrakech [Morocco] to Tunis to Gioia Italy to Tortorello [Tortorella] Italy attached to the 97th Bomb Group (H) AAF-342 Bomb Squadron.

It took the crew ten days to make the Atlantic and Mediterranean crossing. The 342nd had seen combat since 1942. (Memphis Belle was part of the squadron when based in England). By 1944 the 342nd was part of the newly formed 15th Air Force, flying missions against the Axis from Italy.

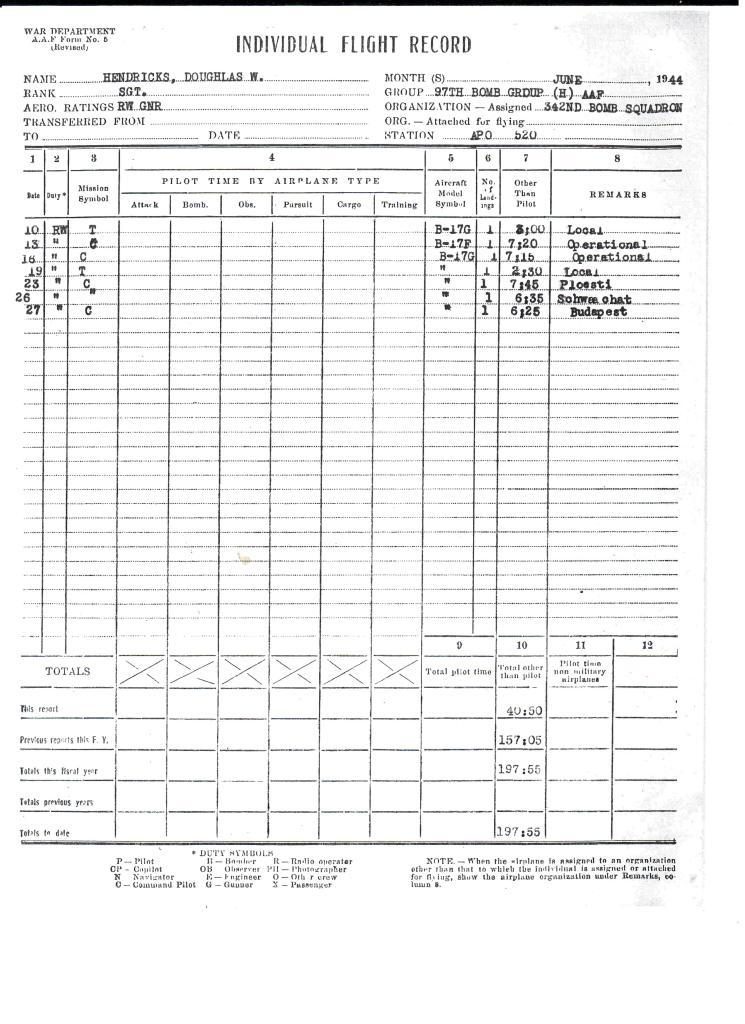

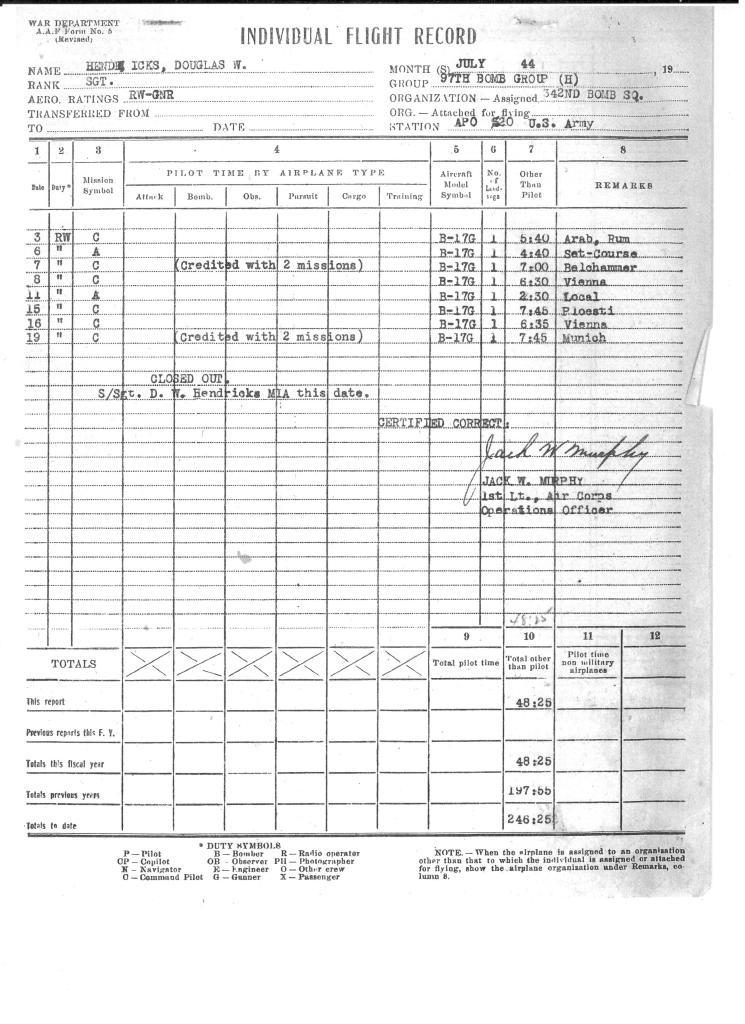

As can be seen from his mission reports, it didn’t take long for the crew to see action over enemy territory. Because of the squadron’s location, their missions were long. The heavily defended Ploesti oil refineries in Romania – 7 hours and 45 minutes. Vienna, Austria – 6 hours and 35 minutes. By July 16th, Tinker’s crew had flown eleven combat missions.

Tinker’s flight log on the B17- closed out when the plane and crew were lost over Germany

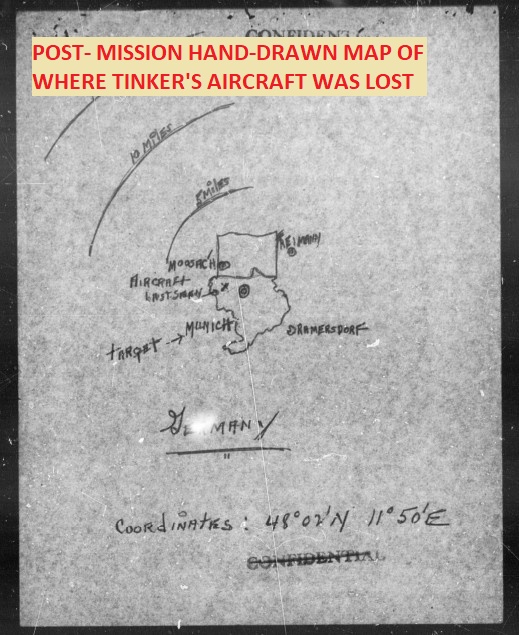

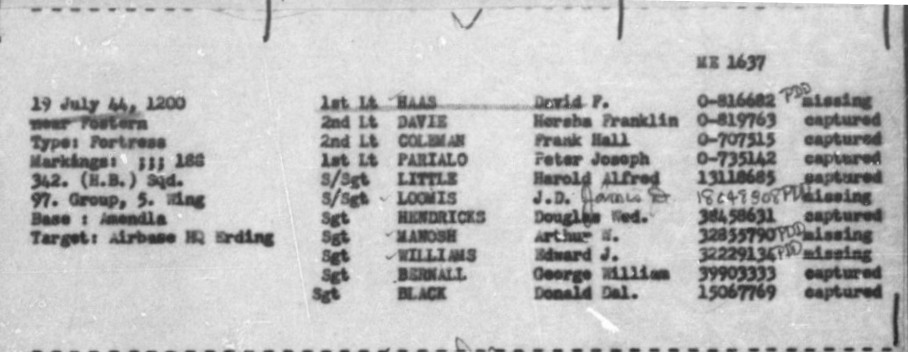

On July 19, 1944, Tinker’s bomber, commanded by First Lieutenant David Haas, took off from Amendola, Italy with a full bomb load. Part of a large formation, its mission was to bomb a ball bearing factory on the north side of Munich. The normal ten-man crew was supplemented with a photographer. The crew consisted of Lt. David Haas (command pilot), Lt. David Hersha (co-pilot), Lt. Frank Coleman (navigator), Lt. Peter Parialo (bombardier), Tech Sergeant James Loomis (radio operator), Tech Sergeant Harold Little (engineer-armorer), Staff Sergeant Arthur Manosh (left waist gunner), Staff Sergeant Douglas Hendricks (right waist gunner), Sergeant Edward Williams (ball turret gunner), Staff Sergeant George Bernall (tail gunner), and Staff Sergeant Donald Black (photographer/gunner). Lt. Parialo, the bombardier, was not part of the aircraft’s regular crew, having been assigned the duties for the one mission.

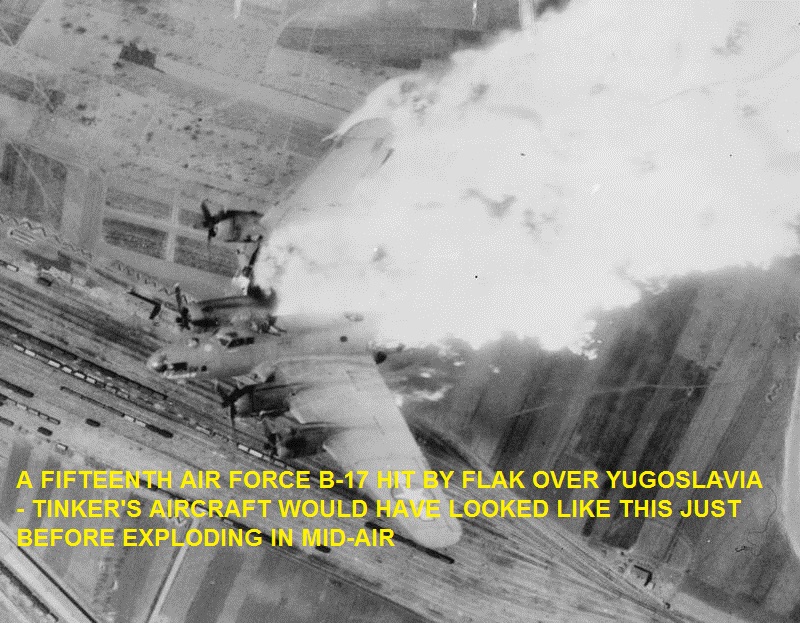

The escorting fighters kept any German fighters at bay. They were no help against German anti-aircraft. As the formation approached the target, the flak became heavier and heavier. Just after the formation released its ordnance from approximately 25,000 feet, Tinker’s B17 took a direct hit on its right inboard engine. The wounded aircraft lagged back and dropped in elevation as Lt. Haas struggled to control it. Less than a minute later, he would be dead.

After the war, Sergeant Little was interviewed. He wrote that the last time he saw 1st Lieut. Haas, the pilot was in the cockpit, and that he could not have bailed out. “According the words of the top turret gunner, the last burst of flak hit the pilot, which caused severe injury and [sic] going down with the ship.”

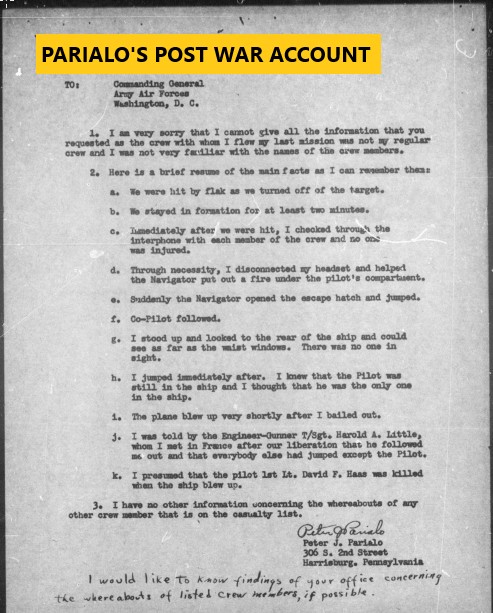

Lt. Parialo, the fill-in bombardier, was interviewed after the war. His recollection was vivid:

- We were hit by flak as we turned off the target.

- We stayed in formation for at least two minutes,

- Immediately after we were hit, I check through the interphone with each member of the crew and no one was injured,

- Through necessity, I disconnected my headset and helped the Navigator put out a fire under the pilot’s compartment,

- Suddenly the Navigator opened the escape hatch and jumped,

- Co-pilot followed,

- I stood up and looked to the rear of the ship and could see as far as the waist windows. There was no one in sight.

- I jumped immediately after. I knew that the Pilot was still in the ship and I though that he was the only in the ship.

- The plane blew up very shortly after I bailed out

- I was told by the Engineer-Gunner T/Sgt. Harold A. Little, whom I met in France after our liberation that he followed me out and that everybody else had jumped except the Pilot,

- I presumed that the pilot 1st Lt. David F. Haas was killed when the ship blew up.

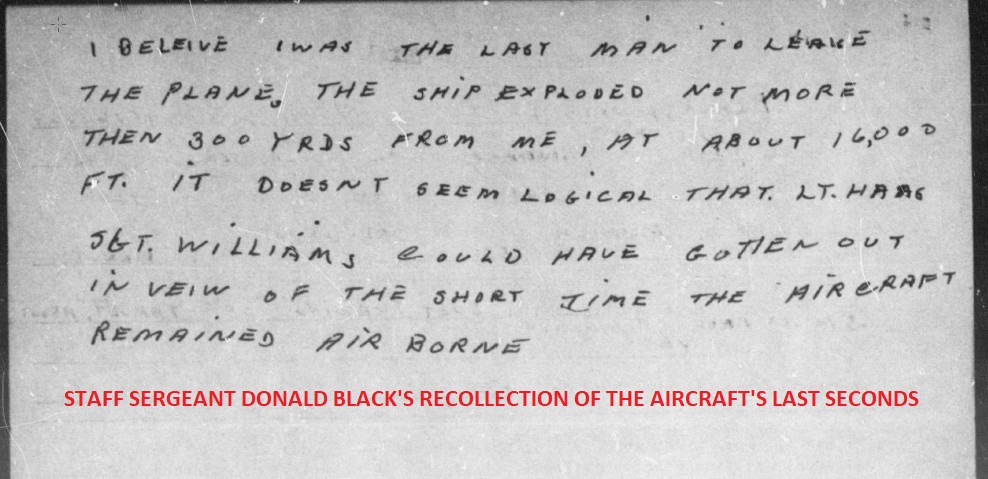

Staff Sergeant Black remembers the event a bit differently:

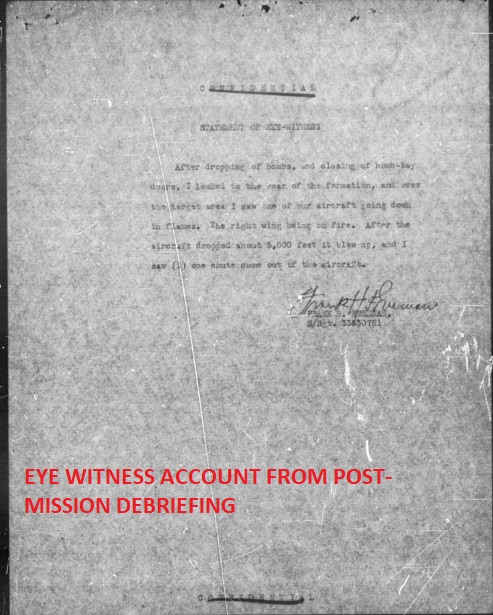

The post-mission interviews tell the chilling story. As shown in the typewritten comments of another aircraft’s crewman: “After it dropped about 5000 feet, it blew up.”

The final tally – seven survived. Four did not. Lt. Haas clearly died when the aircraft blew up. Loomis and Williams may have jumped and couldn’t or didn’t activate their parachutes. Staff Sergeant Manosh was captured, and quite possibly murdered.

Tinker was captured and shipped to Stalag Luft 4, a prisoner of war camp for Allied airmen. The subsequent months were anything but pleasant.

The Men of Tinker’s B-17. Seven captured, and four missing, later confirmed dead

Stalag Luft 4 was located in northern Prussia It held over eight thousand downed airmen. Survival was bleak. The prisoners’ day to day existence was challenged by the weather off the Baltic Sea. By 1944, average Germans were suffering from the Allies’ continuous bombings. While Germany to a large extent attempted to honor the Geneva Convention on captured prisoners, the reality of life in Germany guaranteed that the Allied airmen in Stalag Luft 4 lived a life of deprivation. Inadequate heath and washing facilities, unheated and overcrowded barracks, open air latrines and poor quality food were the order of the day. The prisoners lost weight at an alarming rate. What correspondence allowed was heavily censored. Tinker and the other prisoners of war were not allowed to mention anything remotely disparaging about their condition and treatment.

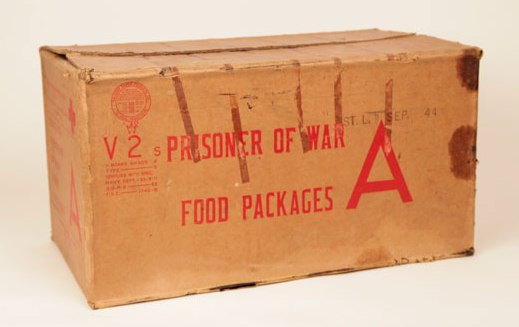

The Red Cross food package – desperately needed

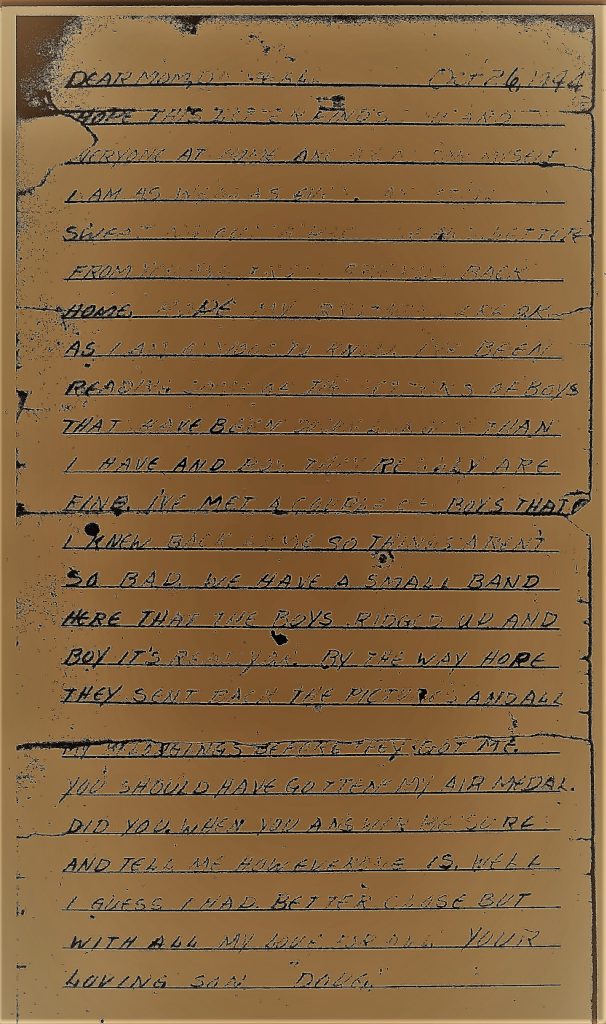

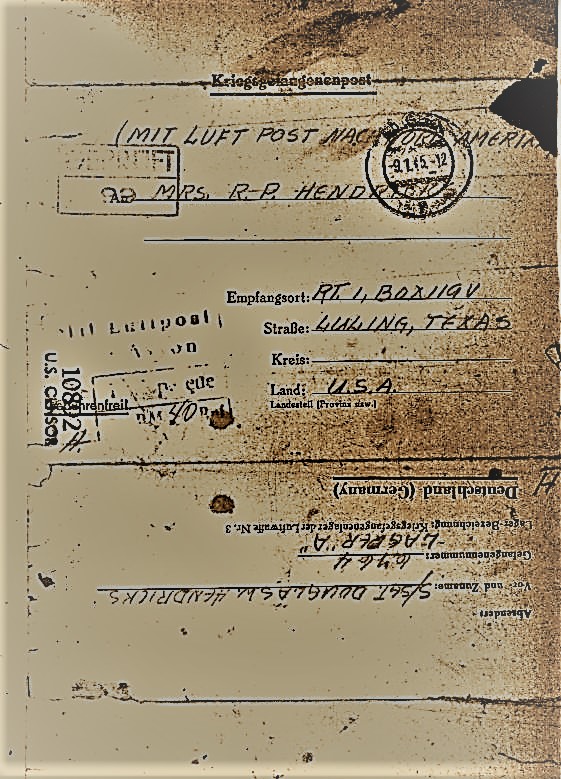

Tinker’s pencil-written letter home with envelope from Stalag Luft IV – October 26, 1944 – the camp guards censored all letters in and out of the POW camp

Delivery of Red Cross parcels was spotty due to the Axis’ damaged rail system. They were a godsend for nutrition and morale. American parcels contained, among other things, Spam, powdered milk, sugar, coffee, tuna, soap, cigarettes, and soup concentrate. Often, the parcels were stolen or pilfered by camp guards.

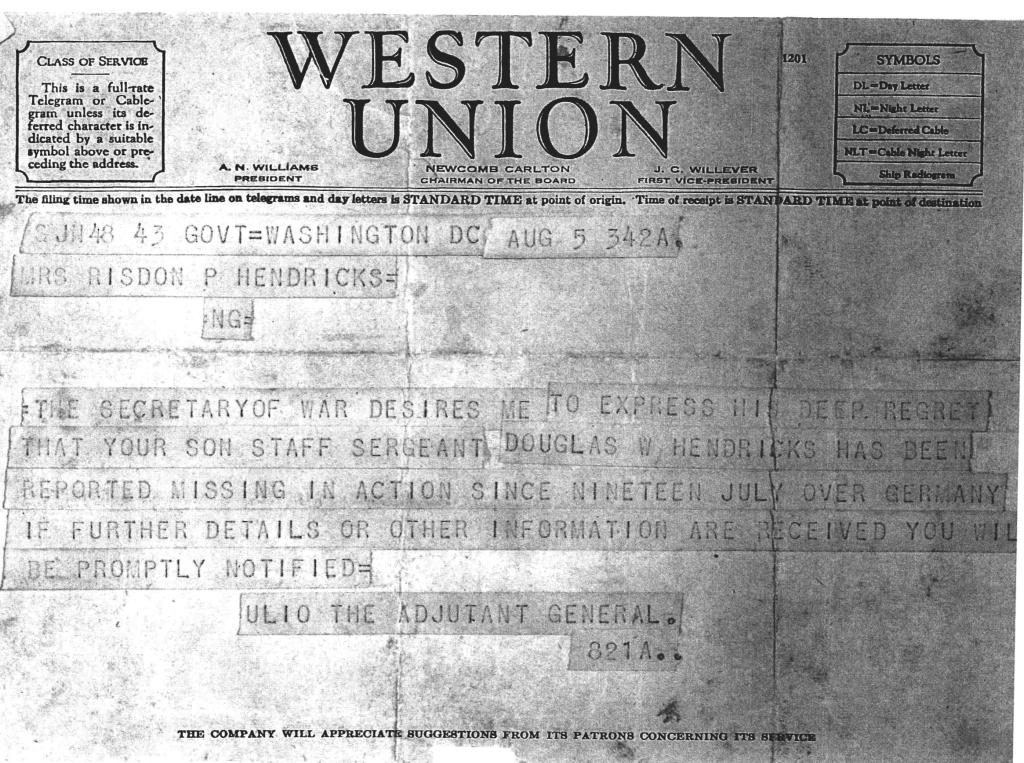

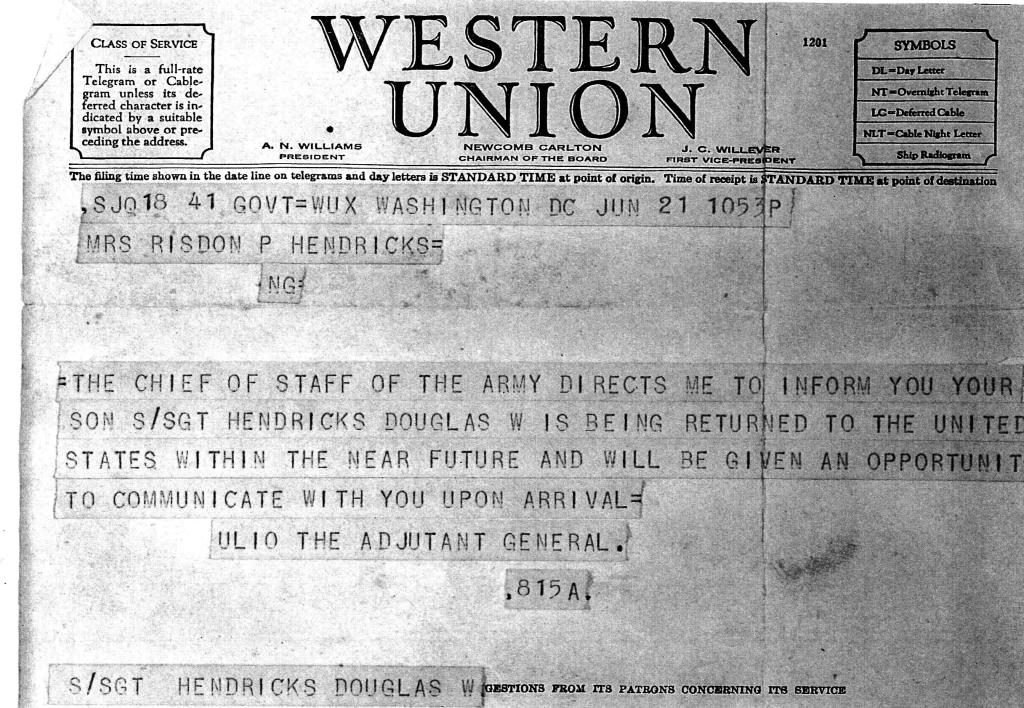

The dreaded telegram – your son is missing in action

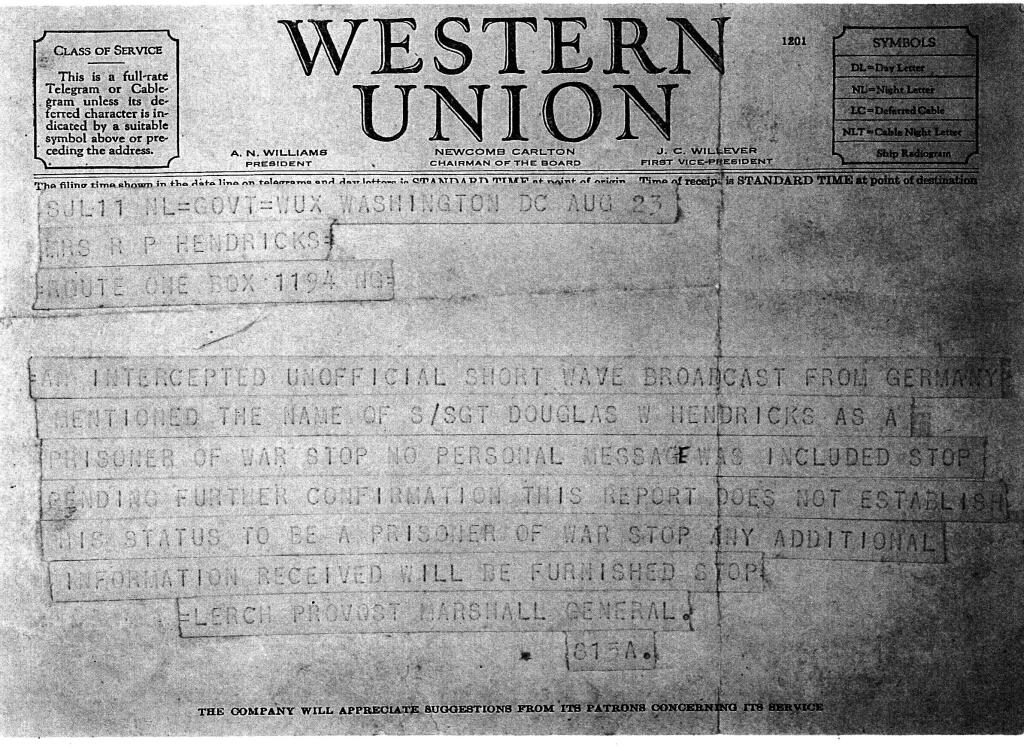

The second telegraph – there is hope

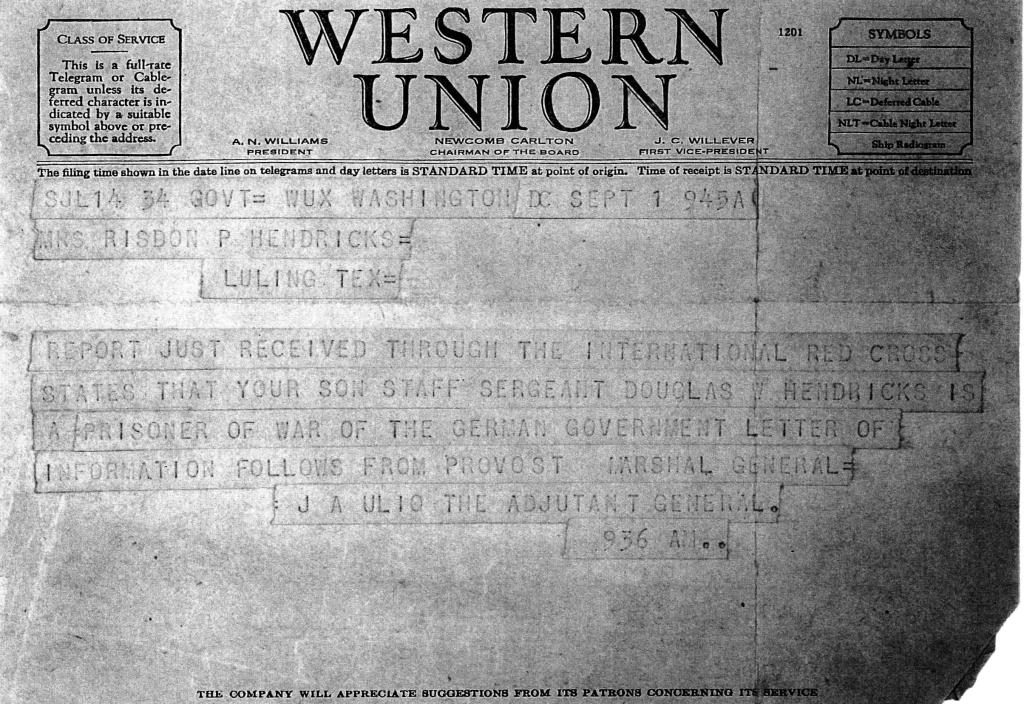

Better – your son is ‘safe’

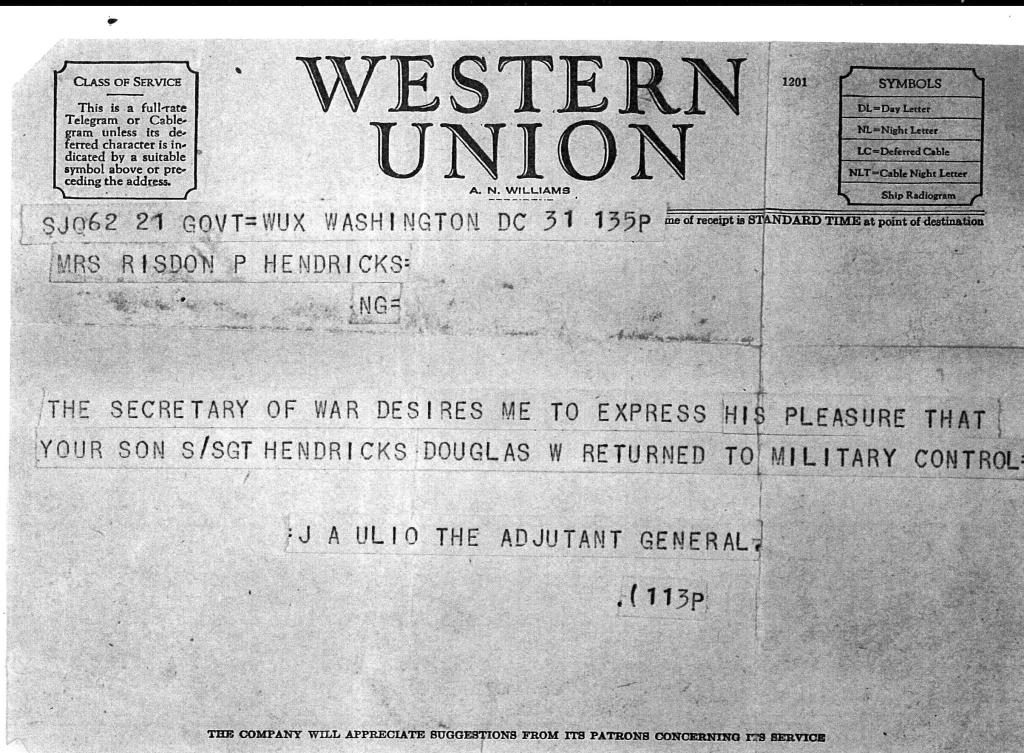

Even better – he is back in friendly hands

The best one of all – you’ll be hearing from him soon

In early 1945, the Soviet advance threatened the German homeland. Rather than releasing the prisoners, the Germans decided to march the Stalag’s POWs west. The result was a grueling 500 mile trek through one of the worst winters in European history. Dubbed the ‘Black March,’ it lasted eighty-six days. The POWs walked up to twenty miles daily, usually sleeping in the open, with little food or water. Collaboration with Germans was forbidden, but often the POWs were able to trade jewelry, watches and cigarettes for food from farmers. Water often came from ditches or snowmelt. Everyone was lice infested. Most suffered from dysentery, which they treated by eating charcoal. Pellagra, typhus, tuberculosis, trench foot, diphtheria and pneumonia were rampant.

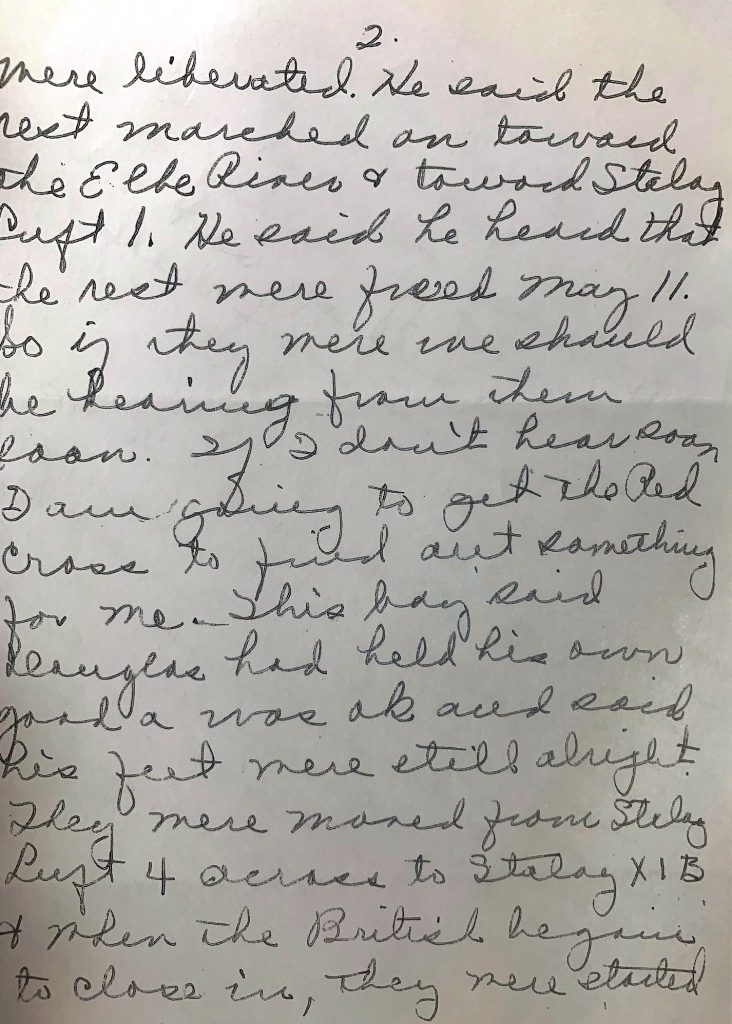

POWs from several camps in the east arrived at Stalag XI-B near Fallingbostel around April 3, 1945. With the Americans and British encroaching from the west, the Germans decided the haggard and unhealthy men were to be moved again – this time to the east. Because of the POWs’ deteriorating condition (and their guards’ awareness that their roles would soon be reversed) they moved only four to five miles a day. Finally, on the morning of May 2, 1945, British forces liberated them.

The men were immediately checked medically, given new clothing, and placed in decent surroundings. With adequate food and medical care, they began to gain weight. Their war now really was over.

Important to the families were the telegrams announcing sons, husbands, and brothers were on their way back to the beloved United States of America.

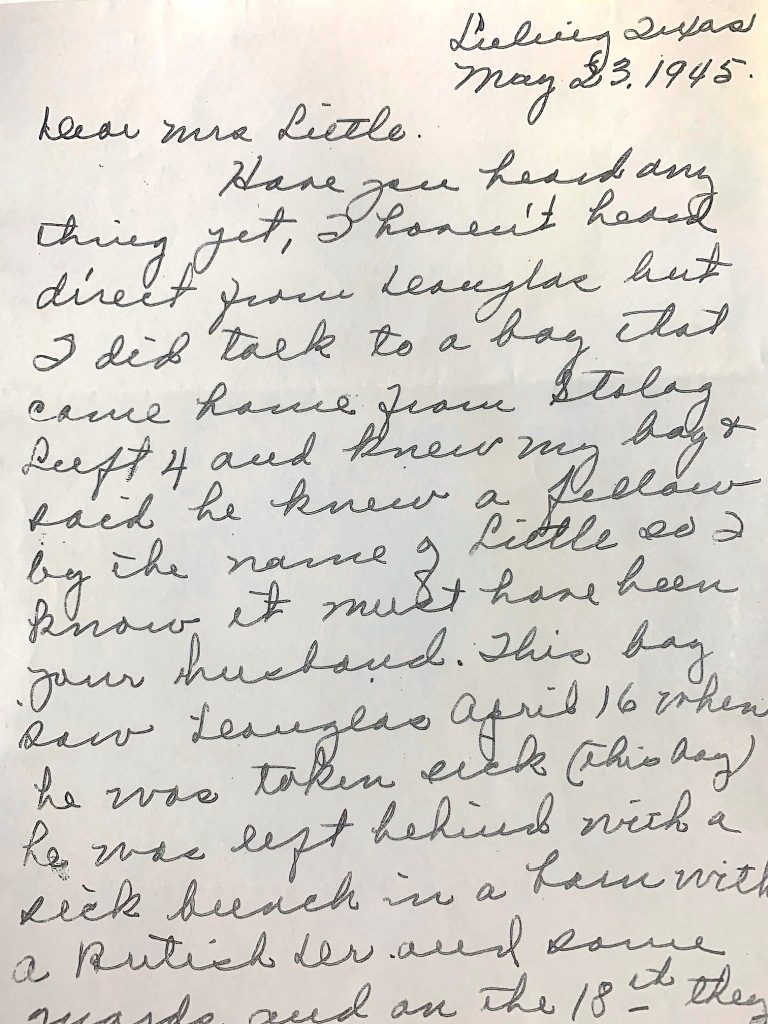

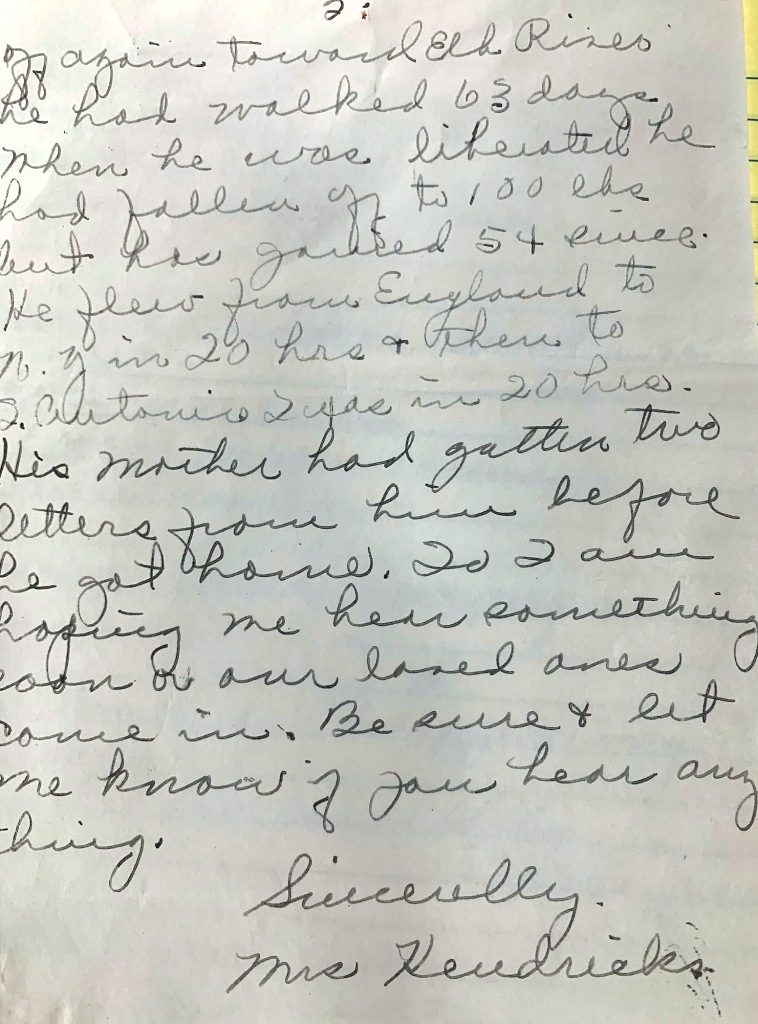

Tinker’s survival was remarkable. Also remarkable was his mother’s correspondence with Sgt. Little’s wife, one which has survived over seventy years. Mrs. Hendricks’ missive, in beautiful cursive, shows her concern, and also shows an amazingly accurate recitation of the Stalag Luft 4 POWs’ trek across Nazi Germany.

Mrs. Hendricks’ letter to Sgt. Little’s wife

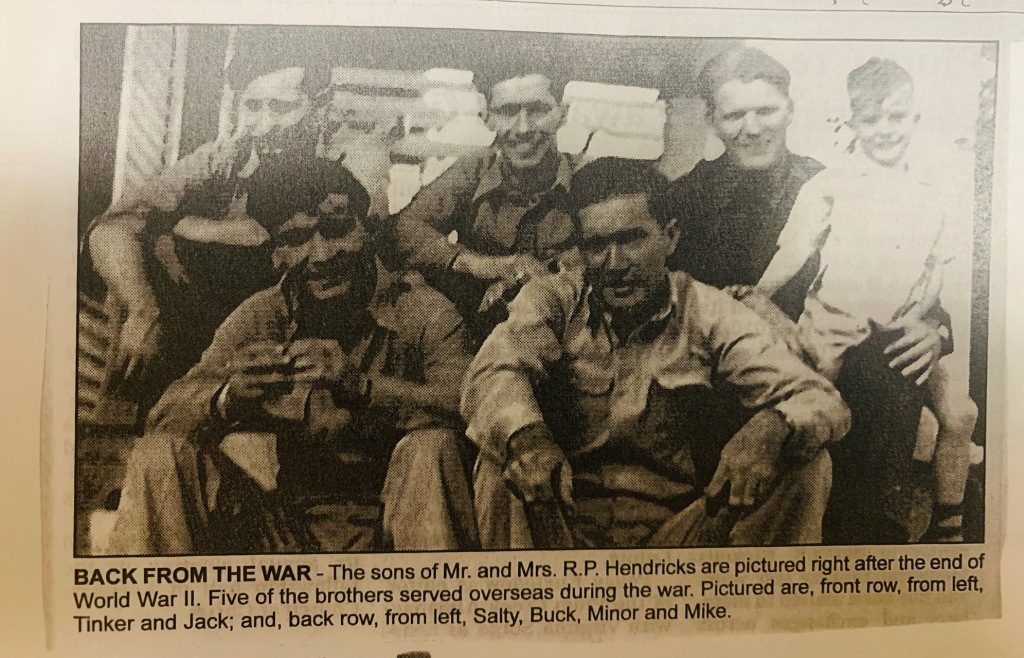

The Hendricks sons reunited – 1946

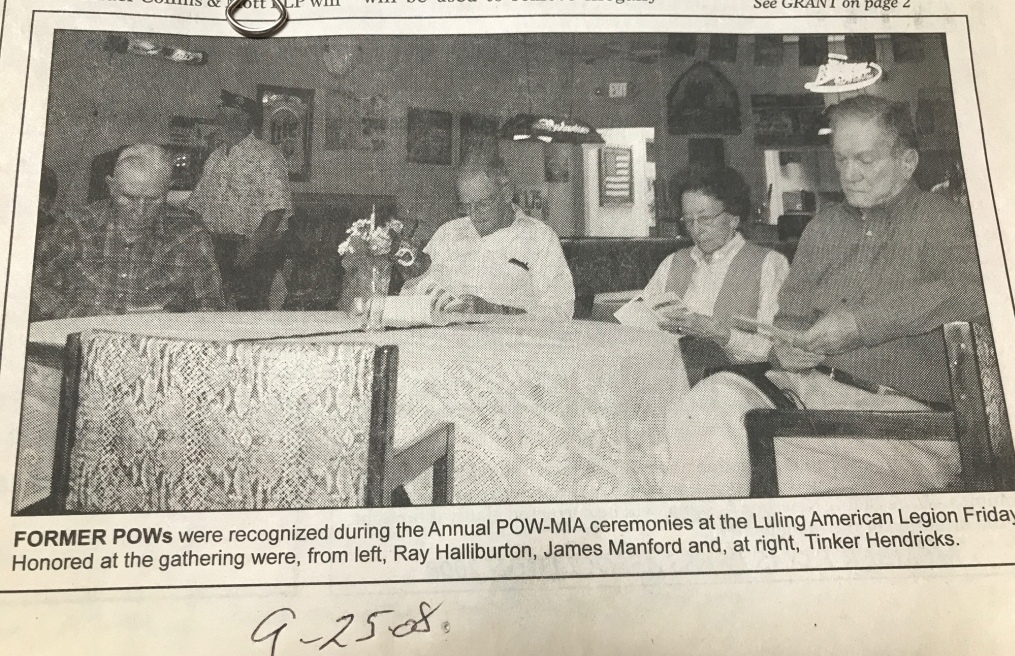

Tinker at the Luling American Legion POW- MIA ceremony – 2008

After the war, Tinker married Beverly Davenport from Prairie Lea. They had one child, Shirley. After Beverly’s untimely death, he married Dorothy Valla. They had two children, Russell and Mark. Tinker worked for Mobil Oil and later for a perforating company. Douglas ‘Tinker’ Hendricks passed away in 2009.

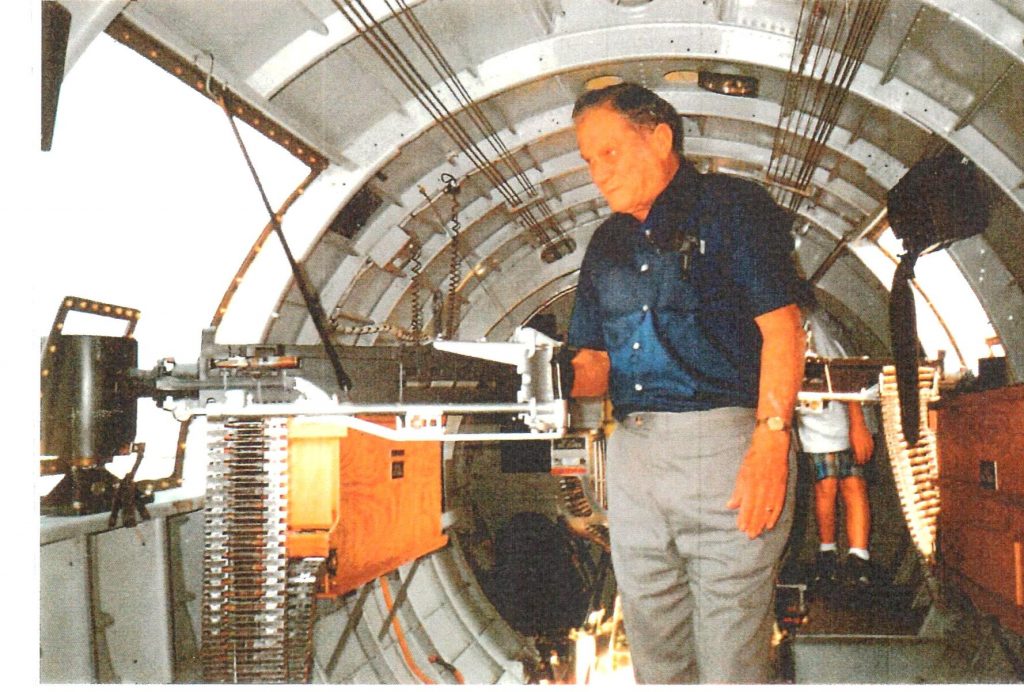

Tinker inside a B17 at an air show in San Marcos. I wonder what was going through his mind.

Like so many of our fighting men of that era, Tinker considered his experience just part of ‘doing his duty.’ His life after World War II was that of a hard working American. He married, raised a family, and had grandchildren. His was a good and productive life. Tinker was proud of his service, but at the same time, didn’t consider it any more that part of his obligation as an American. He kept contact with some of his crew members, exchanging information on families and jobs. There was no bragging or complaining.

He truly was a wonderful example of the Greatest Generation.