by Todd Blomerth

Gus Calhoun Cardwell went by the nickname “Boots” most of his life. He was the son of Augustus Withers Cardwell and Betty Matthews Caldwell. Betty had been a journalist, working for two San Antonio newspapers, and the society editor for the Forth Worth Record, prior to marrying Augustus (“Gus”) in 1916. Gus was a cattleman. The entire Cardwell family was active in the Presbyterian Church

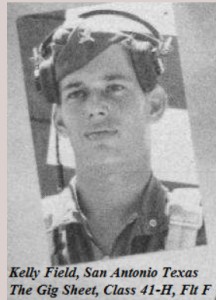

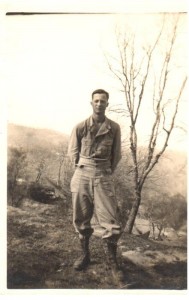

Boots was born on September 16, 1919. He grew up on Trinity Street, and was next door neighbor to the Kreuz family, whose daughter Jimmie would enlist in World War II as a WAAC. During the summers he would work on one of the Withers’ ranches in South Texas. After graduating from Lockhart High School in 1937 he attended Texas A&M for two and ½ years. Boots was Caldwell County draftee number 395, and was ordered to report for induction on March 18, 1941, according to the Lockhart Post Register. In all likelihood he could have stayed at A&M and gotten a commission. Instead, Boots enlisted in the Army, and after basic training was assigned to the 755th Tank Battalion. The battalion had both light and medium tanks, and Boots was in C Company, which was assigned the “Sherman” medium tank. After training at Camp Bowie in Texas and Ft. Knox, Kentucky, the unit was sent to Indio, California for desert training. The unit was then shipped to North Africa, and then to Italy where it entered combat in December of 1943.

The Italian campaign had bogged down by the winter of 1943. Mountainous terrain provided the German defenders excellent positions, and the Allied command, divided between the British led Eighth Army and the American led Fifth Army never achieved anything near the cohesiveness and strategic insight to deal with the situation. By December Allied soldiers were stuck in an array of never ending mountains where brooding peaks held large numbers of well-trained German defenders. Mignano Gap, Rotondo, Sammucro, San Pietro and Cassino became hated names signifying unremitting misery and danger. Assigned to the 45th Infantry Division, the 755th was in the thankless role of trying to advance tanks against well concealed and defended positions sown with land mines. Defending in a series of lines with names like Winter, Bernhardt and Gustav, the attrition rate among the Allies was horrific. As noted by Rick

Atkinson in The Day of Battle, “To cross the seven-mile stretch and pierce the Bernhardt Line had taken the Fifth Army six weeks, at a cost of sixteen thousand casualties.” In January of 1944, the battalion was assigned as support to French Moroccan and Algerian infantry in the French Expeditionary Force. Breaching German defenses entailed bloody fighting and many repulses. Near Leucio, the after-action report for May 20, 1944 states, “The attack finally got started at 1800 under most adverse conditions. The sun and wind was [sic] against us and the enemy threw in a terrific barrage of artillery. The sun, smoke and dusk made the visibility almost nil. The infantry suffered heavy casualties. The attack withdrew at darkness.” The 755th Tank Battalion took heavy casualties as well.

The summary of May’s action contains a litany of complaints about the need for better radio communications, troop coordination, and reconnaissance against hidden anti-tank weapons. But the main complaint reflected what was endemic with all combat units in Italy – the need for better trained replacements, “[T]he trained men lost in combat cannot be replaced, [and] this situation lowers the combat efficiency of the Battalion to a very great extent.”

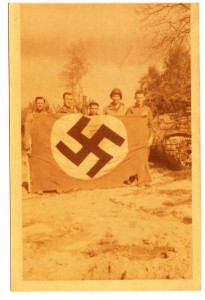

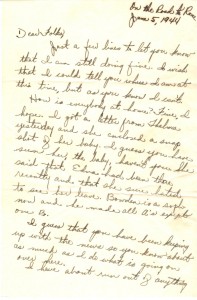

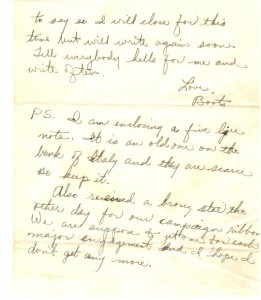

Despite all this, Boots’ letter home of June 5, 1944 sounded cheerful, as he wrote he was “on the road to Rome.” He told his mom and dad that he was “still doing fine,” that his unit had gotten another campaign ribbon, and that “I hope I don’t get any more.” The next day, General Mark Clark’s 5th Army entered Rome. Boots wrote younger brother John, congratulating him on his promotion, on June 11, 1944.

Any expectation of a weakening of the German will to fight after the loss of Rome ended quickly. Pushing northeast, the battalion was hit with intense artillery, anti-tank, and sniper fire. On June 16, 1944 the battalion’s report states in impersonal military language: “Company C supporting 3 RTA advancing toward CASTAGNAIO… from the South met stiff resistance from artillery and anti-tank fire and lost one tank and two crew members by anti-tank fire vicinity A133715.”

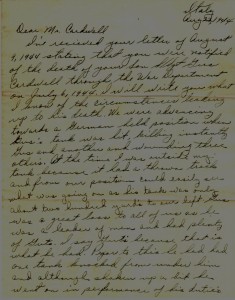

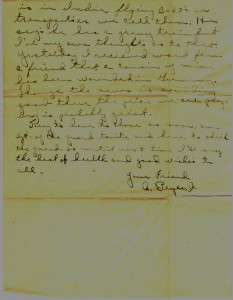

One of the crew members was Boots. His friend from Fentress, Adolphus Beyer, saw him die. “We were advancing toward a German held position,” he wrote in an August, 1944 letter to Boots’ dad, “when Gus’s tank was hit, killing instantly Gus and another and wounding three others. At the time I was outside my tank because it had just thrown a track and from our position could easily see what was going on as his tank was only about two hundred yard’s [sic] to our left.”

Beyer praised his friend as “a leader of men and had plenty of guts. I say guts because that is what he had. Prior to this he had had one tank knocked from under him and although shaken up a bit went on in performance of his duties. “

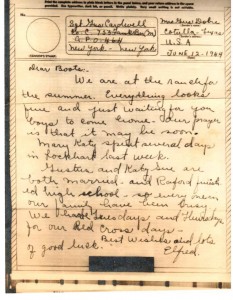

Boots never received the last letter sent him. A “V-mail” missive from a relative in Cotulla, Elfred Wither Dobie, dated June 12th, spoke of the normality that Boots and the rest of those combat yearned for: “We are at the ranch this summer and everything looks fine and just waiting for you boys to come home.”

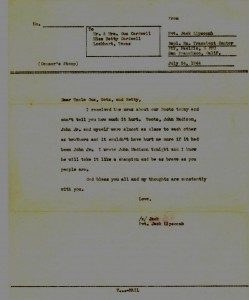

John’s death hit many people hard outside the family. One of his best buddies was Jack Lipscomb. Jack wrote a letter of condolence to the family upon hearing of Boots’ death. Jack would die on Iwo Jima nine months later.

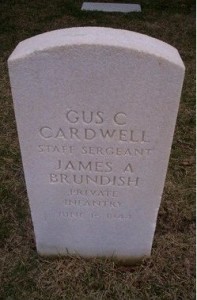

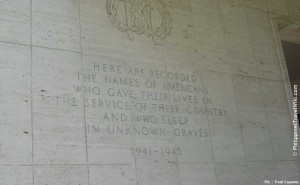

Boots’ remains were buried “in a nice little cemetery in Italy,” according to Beyer. In January of 1950 his remains and those of Pvt. James Brundish, the other trooper killed in the tank, were

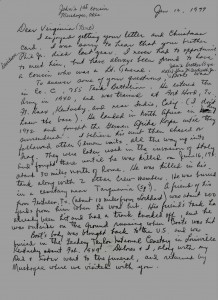

Beyers Letter to the Family – page 1 – April 1945

reinterred in the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky in a single grave. Boots’ dad Gus Cardwell, sister Betty, younger brother John (who had served in US Marine Squadron VMSB 245 as a Dauntless dive bomber radioman and gunner), along with John’s wife Dolores, attended the ceremony.