CURTIS OWEN

A MEDIC FROM MCMAHAN AND THE “UTTER CHAOS OF WAR”

By Todd Blomerth

Imagine yourself as a visitor to Carlsbad Caverns National Park seventy-five years ago, on a tour requiring a long walk down into its vastness. Upon arriving in the Big Room, one of its largest galleries, imagine being seating at a huge formation dubbed the ‘Rock of Ages’ as Park Rangers extinguish all lights, and a recording of the hymn of that name is played. You realize what total darkness really is. Feel yourself blinking as the lights come on, expecting to laugh as you savor a new experience that will help your mile-long trek back to the surface as the tour ends. Then try to imagine your thoughts as a somber Park Ranger announces that he has just received the news that the Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. Imagine the screams of a fellow tourist before she passes out – her son is stationed at the huge Navy base there. Imagine your world changing forever. Private Curtis Owen of McMahan, Texas experienced that on December 7, 1941.

Born in 1919, Curtis was the third of four boys born to Odus and Elizabeth (Handley) Owen. He attended school in McMahan until the ninth grade. His last two years (high school went to the 11th grade in those days) were completed in Lockhart in 1938. Growing up in the Depression, the family kept food on the table farming cotton with mules and horses. Given the cost of horse feed, he often wondered “who was working for whom.”

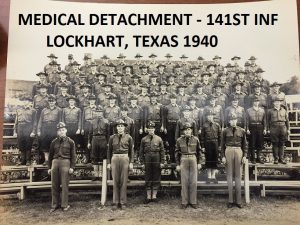

By 1940, it was becoming obvious to many that America would end up in another war, in all likelihood against Germany. Young men were required to register for the draft in September of that year. As a  farmer, Curtis could have claimed a deferment. He chose not to. Despite a farm accident in 1938 that caused the loss of a finger, he also obtained a waiver and, at the suggestion of his family physician, Dr. Joe Coopwood, enlisted in the National Guard’s 36th (“Texas”) Infantry Division’s 141st Infantry Regiment’s Medical Detachment, of Lockhart.

farmer, Curtis could have claimed a deferment. He chose not to. Despite a farm accident in 1938 that caused the loss of a finger, he also obtained a waiver and, at the suggestion of his family physician, Dr. Joe Coopwood, enlisted in the National Guard’s 36th (“Texas”) Infantry Division’s 141st Infantry Regiment’s Medical Detachment, of Lockhart.

Almost immediately after enlisting, Private Owen became part of America’s belated awakening to our country’s dangers. Along with other National Guard units, the 36th Division was mobilized to national service, on November 25, 1940. It is hard to conceptualize today just how unprepared for war our country was. Worldwide, nations had been at war all through the 1930s. For years Americans refused to acknowledge the reality that, like it or not, ultimately our country would have to fight. Training facilities were non-existent. With obsolete equipment and a poor organizational setup, and the total unpreparedness of military officials everywhere, the Division’s attempt to mobilize quickly went FUBAR, or “fouled up beyond all recognition.” The Lockhart Medical Detachment and the Lockhart infantry unit, Company F, were first housed in tents on a drill field where Lockhart’s American Legion Hall is now located. The Medical Detachment’s commander, Major Abner Ross MD, recruited a local cook, and his men ate at their camp. Company F’s men were not so lucky, having to march to the Carter Hotel on the downtown square three times a day for their meals.

In March of 1942 the division’s many units, coming from armories from El Paso to Texarkana, were united at Camp Bowie, near Brownwood. Located in old cotton fields, the camp’s water and gas lines still lay exposed. Men were housed in 5-man tents. For the next six months “we played like we were at war,” said Curtis. Maneuvers in Louisiana showed how unprepared our military was. Trucks were painted white and designated as “tanks.” Bombing raids on the infantry were made with sacks of flour. In November of 1941, Curtis was selected to attend Surgical Technician schooling at Ft. Bliss’ Wm. Beaumont Army Hospital in El Paso. He learned about plasma, sulfa drugs, and emergency care for the wounded. During a weekend break, his class was bused to Carlsbad Caverns. It was on that tour that he found out his country was at war. On December 20, 1941, he graduated tied for first in his class.

The 36th Division trained at Camp Bowie, in the Louisiana Maneuvers, at Camp Blanding, Florida, in the Carolina Maneuvers, and finally at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts. Then its men and equipment were loaded onto ships at New York and sent to Oran, Algeria, in April 1943. Dr. Coopwood, now a major, was the141st’s regimental surgeon. More training ensued, some for amphibious landings, in the squalor and heat of North Africa. By 1943 Private Owen had become Staff Sergeant Owen, and was the senior NCO of the 141st’s 2nd Battalion medical aid station. Thomas William Hazen, a subordinate who became a close friend described Curtis like this: ‘Sgt. Owen, the steady one, who tried to keep this motley group in order, was known as “Colonel.” His Texas drawl was so pronounced I think it sometimes made him laugh with the rest of us.’

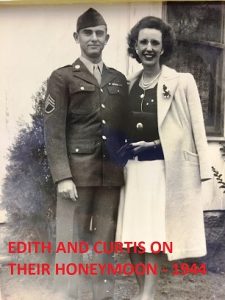

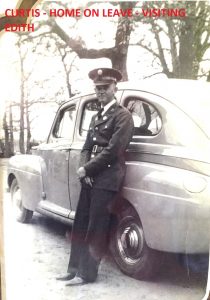

The British and Americans invaded Sicily on July 9, 1943. The 36th stayed in Africa. Would the Texans ever get into the war? All too soon, they did. The 36th Infantry Division was bloodied – and badly – on September 9, 1943 in the Allied landings at Salerno, Italy. The Italians had just surrendered. However, the Germans were aware that it was going to happen, and took over defensive positions. They were waiting when the landing occurred. It was a near disaster, and a foretaste of the debacle called the Italian Campaign. After securing the beaches, bitter fighting continued until the Germans retreated into the mountains north of Naples. The 36th was pulled out of the line to rest and refit in October, and then put back in November, replacing a badly battered 3rd Infantry Division. It fought northward, was pulled off the front line again and then moved by ship to assist in the breakout from the disastrous Anzio beachhead. In July 1944, it was pulled out of the line again, and took part in the landings in Southern France the following month. It raced north in an attempt to cut off retreating Germans. In October 1944, the point system allowed Curtis to come back home for a thirty day leave, which only started once he got to the US. The leave kept him out of the war for nearly five months, because of the transportation difficulties in getting to and from the European Theater of Operations. During this interlude, he married. Curtis and his family were (and continue to be) members of Bethel Primitive Baptist church. At a church conference, he met his future wife, Edith Morrow. Born in Cuero, Edith was raised in the South Texas town of Sebastian, where her father farmed. Curtis and Edith dated until the war separated them. While on leave, Curtis traveled to Sebastian and asked for Edith’s hand in marriage on a Sunday. They were married three days later on  December 13, 1944. Curtis’ parents did not attend the small wedding – he had borrowed the family’s only vehicle and wartime rationing made travel problematic. McMahan is a close-knit community, and many families are interwoven. He says jokingly, “I had to leave home to keep from marrying a cousin!” He rejoined his unit in March of 1945 as it fought through the Siegfried Line. He was in the Brandenburg Alps, at Kufstein, Austria when Germany surrendered in May 1945.

December 13, 1944. Curtis’ parents did not attend the small wedding – he had borrowed the family’s only vehicle and wartime rationing made travel problematic. McMahan is a close-knit community, and many families are interwoven. He says jokingly, “I had to leave home to keep from marrying a cousin!” He rejoined his unit in March of 1945 as it fought through the Siegfried Line. He was in the Brandenburg Alps, at Kufstein, Austria when Germany surrendered in May 1945.

Curtis looks back on his service in World War II with the eyes of a historian. He sees and interprets much of what he endured as part of the big picture. Nevertheless, I asked him of certain instances in his service remain seared in his memory. He paused, and then shared with me some of them.

The Allied landing at Salerno, Italy on September 9, 1943 – His medical detachment rode into the beach on a British landing boat. When the bow ramp dropped, he and everyone on the landing craft were near-casualties. A German machine gunner sprayed bullets at them. Fortunately, the enemy gunner was entrenched too low, and when he depressed his weapon, his rounds struck sand dunes at his front instead of young Americans. Curtis hit the ground, only to feel something kicking him in the side. Rolling over, he looked up at a British MP yelling at him, “Son, get up and off this beach. The bullets won’t kill you unless they hit you.” He got off the beach, but not far that day.

The “utter chaos” (Curtis used that term a lot in his discussions about the war) of Salerno, where the 36th and 45th Infantry Divisions were nearly pushed into the sea – US Navy destroyers cruised close to shore, depressing their guns to drive off the advancing German tanks. The aid station was set up at water’s edge because of the fierce resistance to the landing. The badly wounded were turned over to Navy corpsmen at the beach and evacuated to waiting ships, all the while under fire. Then it was up the ‘soft underbelly of Europe,’ where in Curtis’ words, “there was just one mountain after another.” Mignano, Altavilla, Mt. Rotundo, San Pietro, Sanmucro, and the Rapido River became bywords for misery and death.

The constant replacement of his men – “Each line company was assigned three medics,” he told me. “I lost many of them. Some were killed. Some were wounded.” Many times infantrymen were pulled out of companies and made stretcher-bearers. Toward the end of the war, personnel shortages were so critical that prisoners in army guardhouses were returned to the line, if they agreed to behave. The Medical Detachments got some of them too. They usually did a good job.

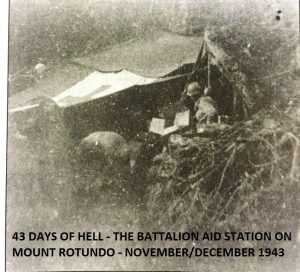

The necessity of finding a place for medical facilities – “We were usually around one mile from the front lines,” he said, “which was well in range of artillery.” If lucky, they found suitable structure where medics and doctors could work in blackout conditions. But weren’t structures also artillery registration points – in other words, targets? “Well, yes, but that was a chance we had to take so we could work on the wounded.” Until prodded, Curtis said nothing of his Purple Heart – he took shrapnel in a hand in late 1943. The picture below, taken from Hazen’s book, “Medicos Up Front – With the 36th Texas Infantry Division,” shows the 2nd Battalion’s aid station in November and December 1943.

For 43 days, in mud, rain and snow, and with mortar barrages which missed (but barely) Sgt. Owen’s men struggled to save lives. Hazen describes their existence:

The Aid Station was located on a mountain trail impossible to reach by jeep and several hundred yards from a point where a jeep could get in. there is where we established our collecting point to be used sparingly during daylight. (light discipline was strict). At night a jeep would bring water and food to the collecting point and then take the dead in body bags (mattress sacks) back to Graves Registration for burial. In order to evacuate the severely wounded promptly in daytime, our drivers had to chance being observed. …One canteen of water was each one’s ration for the day and it was used for drinking and cleanliness. Our clothing could not be changed for 43 days.

The death of Lockhart’s Dr. Joe Coopwood – Major Coopwood was not required to visit aid stations, but he did, and regularly. He was at the 2nd battalion’s Aid Station the day before he died. His last words to Sergeant Owen as he left were, “I’ll see you day after tomorrow.” It didn’t happen. The 141st’s regimental surgeon was killed at regimental headquarters by long-range artillery the following day. “He was like a father to us. His death really affected me. I knew he was different from other doctors. Before going to medical school he had attended VMI. He was a soldier’s soldier.”

The horrific blunder of the Rapido River crossings of January 20 and 21, 1944 – The 36th’s commander, General Fred Walker, told higher authorities that attacking across a river into the main German defensive positions would be suicide. Despite this, he was ordered to move two of his regiments across the swift moving stream and then attack the entrenched enemy. The two attempts turned into a slaughter, as men and rubber boats were riddled with artillery and machinegun fire. Although a toehold was made, the survivors had to retreat. Of the 6000 men involved, over 2000 were wounded, killed or captured The Germans suffered less than 300 casualties. Three days later, a four-hour truce was called, so the Americans could recover their dead. Sergeant Owen was ordered to dispatch two medics with a white flag, where a truce had been arranged. “I recall the silence,” he said. Almost continuous artillery fire had, for a brief moment in time, ceased. “After four hours, the truce was over with, and things started back up again.” Curtis understates his own involvement. Hazen remembers that ‘[a]s might well be expected, Sgt. Owen told the captain that he could ask none of us to go unless he himself went also. [The detachment commander] said that he would not permit the sergeant to go for he felt that these two men might not come back. The captain could ill afford to lose the services of Sgt. Owen.” He would later receive a commendation for “exceptionally meritorious conduct” for his work evacuating the wounded the following month.

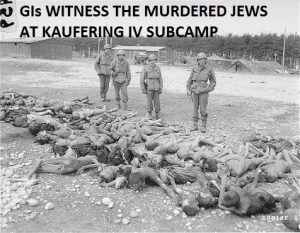

The horrors of Kaufering, one of the many Dachau sub-camps – Although Nazi extermination camps were in Poland and elsewhere, Germany was home to over 20,000 labor, transit, and concentration camps between 1933 and 1945. The camps in Germany used Jews, Gypsies, political and social undesirables, and Russian POWs, as forced labor. Hundreds of thousands vanished due to starvation, disease, and outright murder. Like other Allied units, the 36th came upon the horrors of unbelievable inhumanity. Beginning in 1943, Kaufering’s inmates – mostly Jews – were forced to excavate underground facilities for fighter aircraft production. As the Allies approached in late April 1945, the SS forcibly evacuated surviving inmates and murdered those too ill to move. Curtis and thousands of other GIs witnessed these horrors. Of his experience, Curtis says little, just shaking his head.

camps between 1933 and 1945. The camps in Germany used Jews, Gypsies, political and social undesirables, and Russian POWs, as forced labor. Hundreds of thousands vanished due to starvation, disease, and outright murder. Like other Allied units, the 36th came upon the horrors of unbelievable inhumanity. Beginning in 1943, Kaufering’s inmates – mostly Jews – were forced to excavate underground facilities for fighter aircraft production. As the Allies approached in late April 1945, the SS forcibly evacuated surviving inmates and murdered those too ill to move. Curtis and thousands of other GIs witnessed these horrors. Of his experience, Curtis says little, just shaking his head.

Starving displaced persons and freed inmates from concentration camps – After Dachau, the Division was on K rations. The GIs did not have spare food to distribute to the thousands of displaced persons and camp survivors that were, seemingly, everywhere. Sergeant Owen, the erstwhile farmer, knew something about places where these unfortunates might find some stored foods. He “suggested” to some that they look in Germans’ cellars. Many did, finding stores of potatoes, which they were able to boil and eat. They also discovered schnapps and wines, and some got quite drunk very quickly.

German autobahns filled with enemy soldiers marching to surrender in late April and early May – The average soldier knew their country was defeated. Only fanatical SS units thought otherwise. SS men hung or shot “defeatists.” Curtis recalls one group explaining that they had to kill several SS men so they could surrender.

The countenance of captured Nazi SS soldiers: “I only saw a few,” he tells me. “But the ones I did see had dead eyes.”

The emotional and psychological costs of war: War became unreal. “If you thought about it too much you would go stark raving mad,” he recalled. “You see so much suffering your mind goes blank.” But not perfectly. By the end of the war, if he saw someone badly wounded, “I had to get up and leave.” The war’s horrors stayed with him afterward. When asked, Curtis acknowledged quietly it took a toll on him. As we talked, Edith nodded. Although not discussed, she too witnessed Curtis’ suffering in those years. He told me the hours spent alone as a farmer helped put the demons to rest. There is no doubt that a strong and loving wife and family, and a deep Christian faith helped as well.

After Germany’s surrender in May, 1945 hundreds of thousands of

GIs spent months awaiting transportation home. Most finally went by ship. Tech Sergeant Curtis Owen (he had been promoted) got lucky and hopped a ride on a four engine bomber. With fueling stops at Marseilles, Casablanca, the Azores, St. John, and Presque Island, it reached Boston. Then it was by train to San Antonio. He arrived home on August 1, 1945. At last, his war was over.

GIs spent months awaiting transportation home. Most finally went by ship. Tech Sergeant Curtis Owen (he had been promoted) got lucky and hopped a ride on a four engine bomber. With fueling stops at Marseilles, Casablanca, the Azores, St. John, and Presque Island, it reached Boston. Then it was by train to San Antonio. He arrived home on August 1, 1945. At last, his war was over.

Ed Horne, the local Farmall dealer, knew Curtis was a returning veteran, and put his name at the top of the list for a new two row tractor. He continued to farm for sixty years.

Curtis and Edith celebrated 71 years together recently. They have been blessed with three children (Diane Ross, Beverly Coates, and Tom Hazen Owen), seven grandchildren, and fifteen great grandchildren. Curtis and Edit h now reside at the Golden Age Home. Their warmth and kindness are infectious. They and their family have done much to enrich Caldwell County. Drop by some time.

Curtis and Edith Owen and Their Grandchildren and Great Grandchildren

ADDENDUM 11-15-17

I wrote this story in February of 2016. I visited with Curtis today at a local nursing facility. He recently fell and broke his pelvis. He was recovering nicely. His bride of 72 years had recently passed away. Curtis continued, at the age of 98, to be mentally sharp as a tack. We discussed world affairs, and Curtis expanded a bit on the effects of the war on him. “There were a lot of funerals i didn’t attend [after the war]. I’d seen too much.”