This story, researched by the hard working folks of the Caldwell County Genealogical and Historical Society, appears in the Fall 2018 edition of the award winning Plum Creek Almanac, the Society’s semi-annual publication.

THE NEWSPAPERS OF CALDWELL COUNTY, TEXAS

By

Todd Blomerth

Almost as soon as Caldwell County was created, attempts began to satisfy its citizens’ thirst for news and opinion, and news publications of various types were begun in various parts of the county. Sadly, newsprint is ephemeral. Many newspapers appeared, and as quickly, disappeared. Some are known only because of brief comments in other publications of the time. Some publications merged. I suspect that no one got rich in the newspaper business. The hours were long, the printing process tedious, and, like today, the risks of offending the powerful often real. This article is an attempt at listing all newspapers (or similar periodicals) known, or at least suspected, of existing in Caldwell County.

- The Rustler – Martindale, Texas, circa 1900. Editor – W.R. Hadley.[1] References to the Rustler appear several times in the Lockhart Weekly Post and the Lockhart Post, between 1900 and 1904. The San Antonio Express shared society snippets from other newspapers, as was the custom of the time. On November 5, 1899, it copied a Lockhart story that told that “Editor W.R. Hadley of the Martindale Rustler was in the city last Tuesday.”[2] The Lockhart Weekly Post of September 19, 1901 reprinted two news items from the Rustler: “The hardest rain we have had in twelve months fell here last Saturday. It was a regular ground smoker and tank filler.” – Martindale Rustler. The prohibition election in the Staple precinct last Saturday resulted in a victory for the prohibitionists. The vote stood 202 to 68. – Martindale Rustler.”[3] No copy has been found.\

- The Enterprise – Martindale, Texas – circa early 1900s. Editor – T.F. Harwell. It was “suspended after a short time because the business interests were not [unreadable] to give them the necessary support.’”[4] No copy has been found.

- Fentress Indicator – Fentress, Texas, 1903-? Editor – W. Davis. “Fentress is a growing town in the San Marcos valley and in the famous “black land” district, where an enormous lot of truck is grown by the irrigation plan. This location makes the INDICATOR a valuable advertising medium. Rates on application.”[5] No copy has been found.

- Luling Commercial – Luling, Texas – 1870? – Editor – S.C. Craft. The only mention of this publication is in the Brenham Weekly Banner of February 1, 1878: “S. C. Craft, editor of the Luling Commercial, died on the 25sh [sic[ inst. At Luling. He was quite an elderly gentleman.”[6] No copy has been found.

- Luling Reporter – 1870(?) Editor – S.C. Croft. Nothing is known of this publication apart from the following in the Denison Daily News of January 29, 1878: “Rev. S.C. Croft, editor of the Schelenburg [sic] Argus, died at Luling on the 25th Inst., at a very advanced age. Mr. Croft once edited the Luling Reporter.”[7] It is likely that the references to ‘Croft’ and ‘Craft’ are to the same person. Whether he operated one or two newspapers is not known.

- Luling News – ?-1896. Editor – B.H. Goode. The only mention of this publication is in the Galveston Daily News, which on September 18, 1896 reported: “Luling, Tex., Sept. 17. – B.H. Goode, former editor and proprietor of the Luling News, has resumed control of the property and closed the News office. He has decided to remove the entire plant to Calvert, Texas and start a new weekly there. This leaves the old established Luling Signal in sole control of the journalistic field there.”[8] No copy has been found.

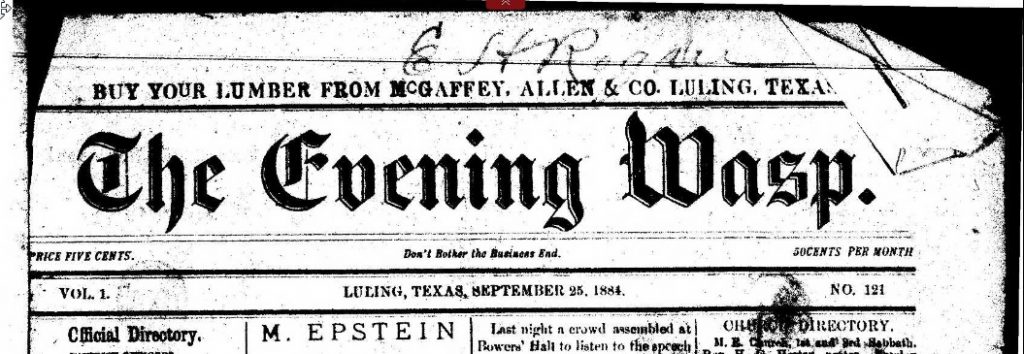

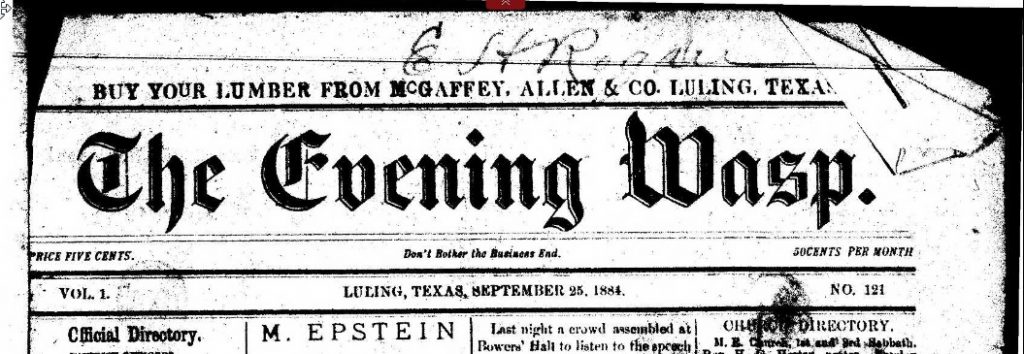

- Luling Wasp (Luling Evening Wasp) – 1884-?. Editor – Jason Hodges. Virulently anti-Republican, its editor described Jefferson Davis as a “venerable patriot.” He went on to aver that “[T]he republicans deny the capacity of the people for self government, while the democratic party affirms it…”[9] Showing the anger of white Southerners toward the recently ended Reconstruction period, Hodges proclaimed that “[I]f Geo. Washington himself was a candidate before the people of Texas, upon the record the Republican party presents, he would be defeated.”[10] His disapproval of African-Americans’ right to vote was most evident.

- Luling Auger – 1882-? – Editor- unknown. In 1882, the Galveston Daily News reported that “The Luling Auger is to be the titled of a new paper to appear on the 9th of December, in Luling. As the prospectus says: It will be devoted to local and miscellaneous matters, and will contain a little of everything, except spring poetry and dead-head puffs.”[11] No copy has been found.

- Luling Gimlet – 1885 – ? Editor unknown. The only mention of this publication was found in a Dallas Morning News article entitled “Dallas and Texas 50 Years Ago,” published in 1935 and referencing an 1885 story, which noted that “Luling has

a new paper. It is called the Gimlet.”[12]

- Texas Baptist Record (Luling) – 1891-?. Editors – J.P Hardwick, Sr., and R.R. White. The Fort Worth Gazette, in its “Texas Journalism” column, mentions that “Luling now has two religious papers – the Signal and Texas Baptist Record. The Signal was started several years ago by Col. J.P. Bridges. The Texas Baptist Record is a new paper, having been started by J.P. Hardwick, Sr., and R.R. White.”[13] No copy has been found.

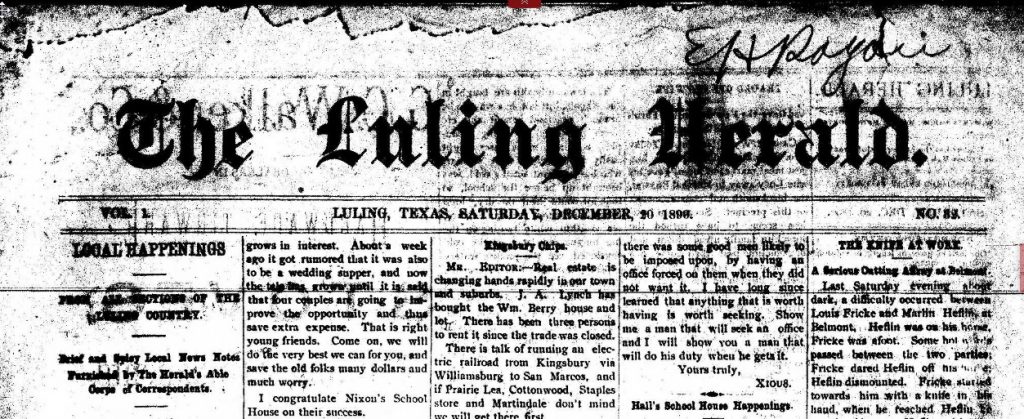

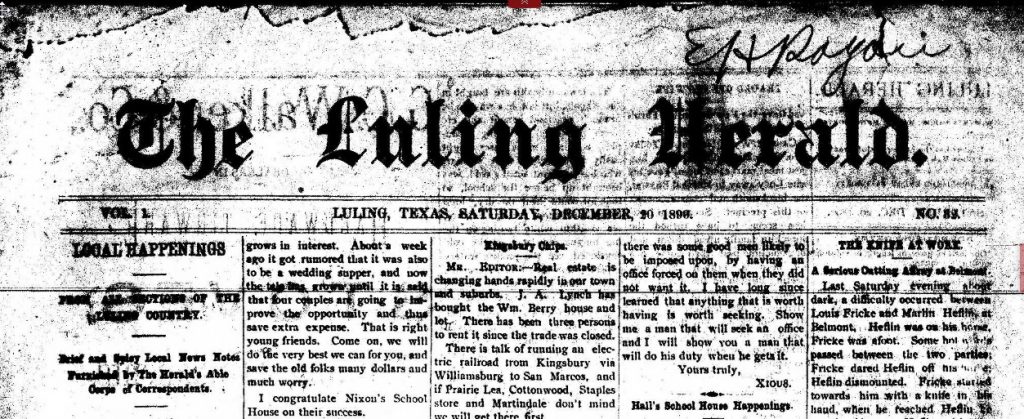

- Luling Herald – 1890-1893. Owner/Editor – W.B. Stevens. Editor 1891-1893 – J.D. Sanders. The Galveston News announced on May 4, 1890 that “t]he first issue of the Luling Herald is just coming from the press. It is a neatly printed five column eight page paper. The proprietor is W.B. Stevens, recently from Del Rio.”[14] The Herald and Signal teamed up “and got out a big double-sheet special edition” in 1890 touting the young city’s pluses, its railroad, and its cotton gins.[15] The Herald printed one thousand copies of a special edition in 1891, to be distributed “throughout the county in the interest of immigration.”[16] It consolidated with the Luling Signal in 1893.[17]

- Luling Enterprise – Circa 1901. Editor – Maurice Dowell, and later, George P. Holcomb and Jeff P. Sanders. Described as a “neatlygotten up 7-column folio.”[18]It is unknown whether this was in any way related to the Martindale publication with the similar name. A give-and-take between its editor o and the Lockhart Register’s editor appeared in the Lockhart Register regarding prohibition and criminality:

The Lockhart Weekly Post editor’s comments seem to indicate that the Luling Signal and the Luling Enterprise were perhaps in cahoots, or jointly owned.[19] Apparently they weren’t. The Enterprise’s editor groused publicly about subscribers dunning it and jumping to its competitor. In 1902, the Bastrop Advertiser mentioned the paper’s gripes:

There is hardly a newspaper in all Texas that has not often met with the experience of the Luling Enterprise, as expressed in the following: “We notice that the Signal has secured several new subscribers in the past several weeks that once took our paper. What we want to say is that they dead beated us out of money. We hope the Signal will get their money allright and have no such dirty trick played one it.”[20]

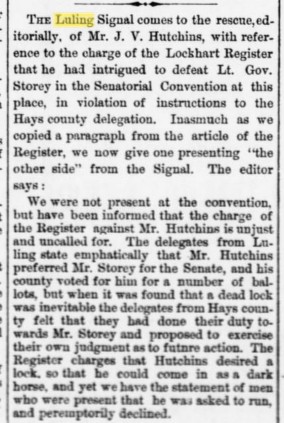

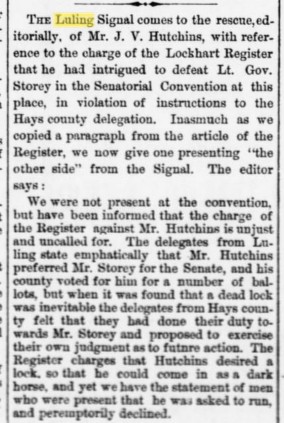

- Luling Signal – (Also published as Luling Signal and Tri-County News in 1939) – 1878-1974, 1977-1978. Publisher/editor – J.P. Bridges 1878-1893). Later editors: Mrs. A.C. Bridges, S.W. Huff, W.B. Stevens, J.W. Browne, J.D. Sanders, M.L. Carter, Mr. Walker, D.C. Holcomb, J. P. Bridges, H.F. Bridges, and L.H. Bridges.[21] J.P. Bridges sold his interest in the Lockhart News-Echo in 1878 and started the Signal the same year, operating it until his death in 1893. Its inaugural edition was described as a “handsome paper, the first number of which appear, at the flourishing town indicated, on the 10th instant.[22]A report in the LaGrange Journal of 1883 stated that “Col. Edmonson of the Flatonio [sic] Argus has bought the Luling Signal and will move to Luling. Col. E. is a thorough newspaper man and will make the Signal a signal success.”[23] This transaction apparently never transpired, as Bridges continued as the owner. The newspaper merged with the Luling Newsboy in 1978. It appeared under various titles through the years, including Luling Signal and Tri-County News (in 1939) and Sunday Signal. Austin’s Weekly Democratic Statesman of January 17, 1878 noted: ‘The Signal has made its appearance at Luling. It is a handsome sheet and reflects credit upon the community in which it is published.”[24] In an 1880 snippet, the Brenham Daily Banner’s editor joked about fellow newspapermen and their marital status: “The Gonzales Inquirer man takes a fit every time an editor gets married. The Luling Signal man and the Houston Post man have been married lately and now the Inquirer man sits and think of the time when he should do likewise.”[25] Not afraid to mix it up, the Signal’s editor took issue with its Lockhart counterpart over state political machinations:[26]

J.P Bridges put out a good paper as reflected by these comments in 1885: “The Luling Signal has been enlarged to a 32-column paper and presents a beautiful appearance. Bridges is a whole team, as a newspaper man, and gets out a rattling good paper. Hope he may continue to prosper.”[27] J. P. Bridges was well respected by other newspapermen. In 1891, he helped call a meeting of editors, in hopes of creating a permanent organization entitled “Editors of the Southwest.” It’s inaugural meeting was held in Aransas Harbor [Port Aransas?].[28]

The paper ceased production in 1974, but restarted in August of 1977. It was consolidated with the Newsboy in 1978.[29]

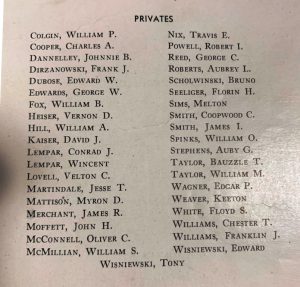

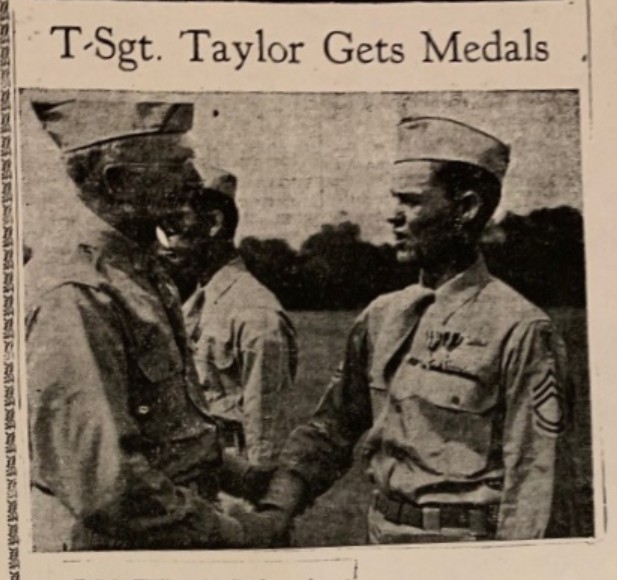

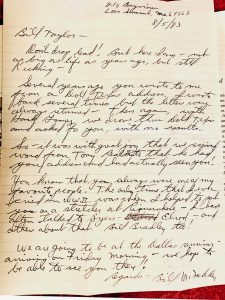

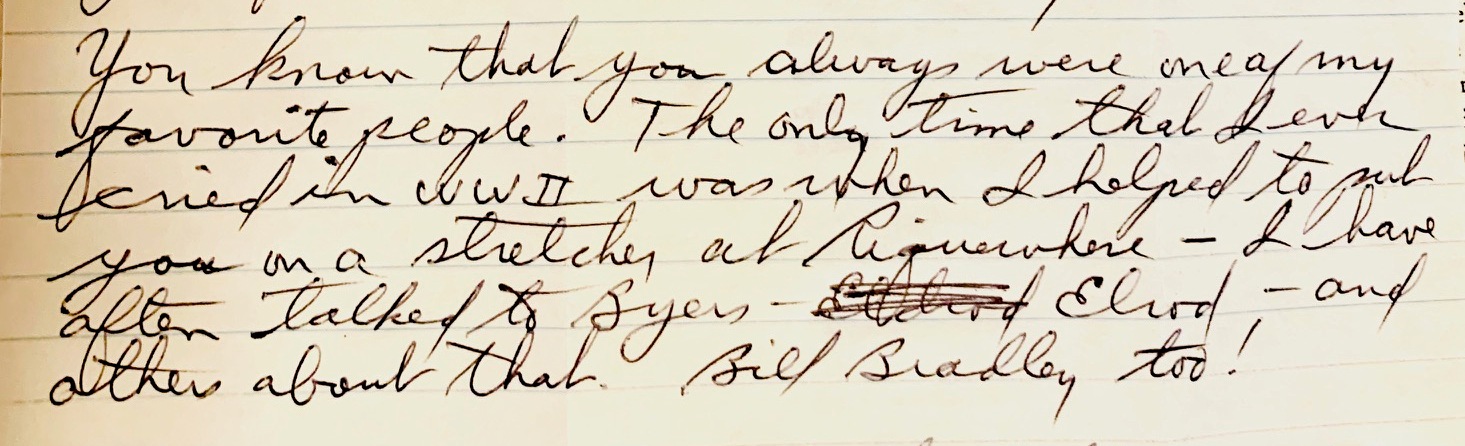

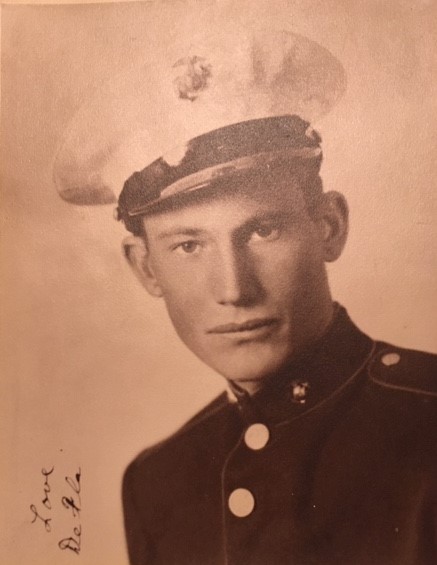

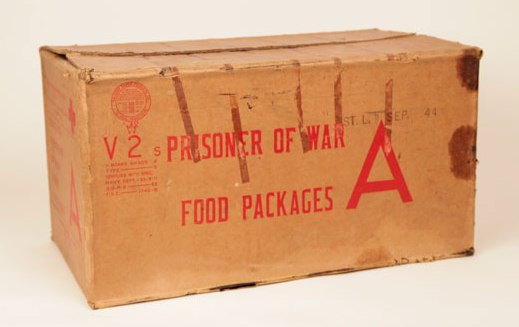

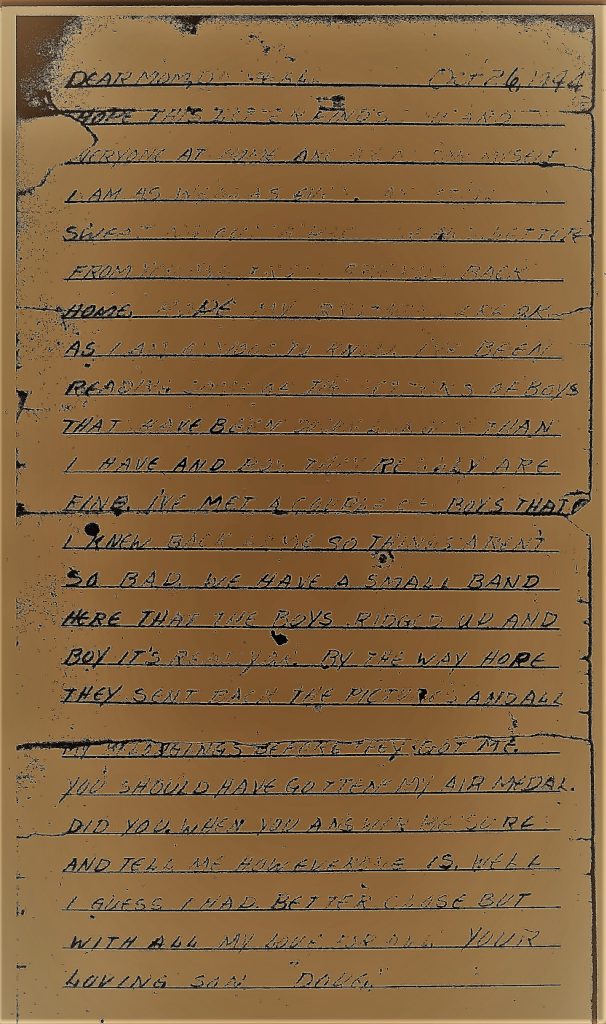

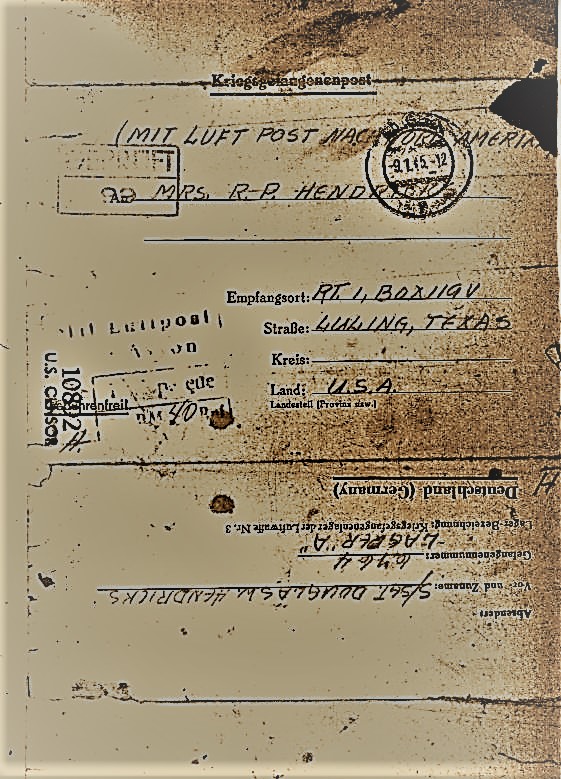

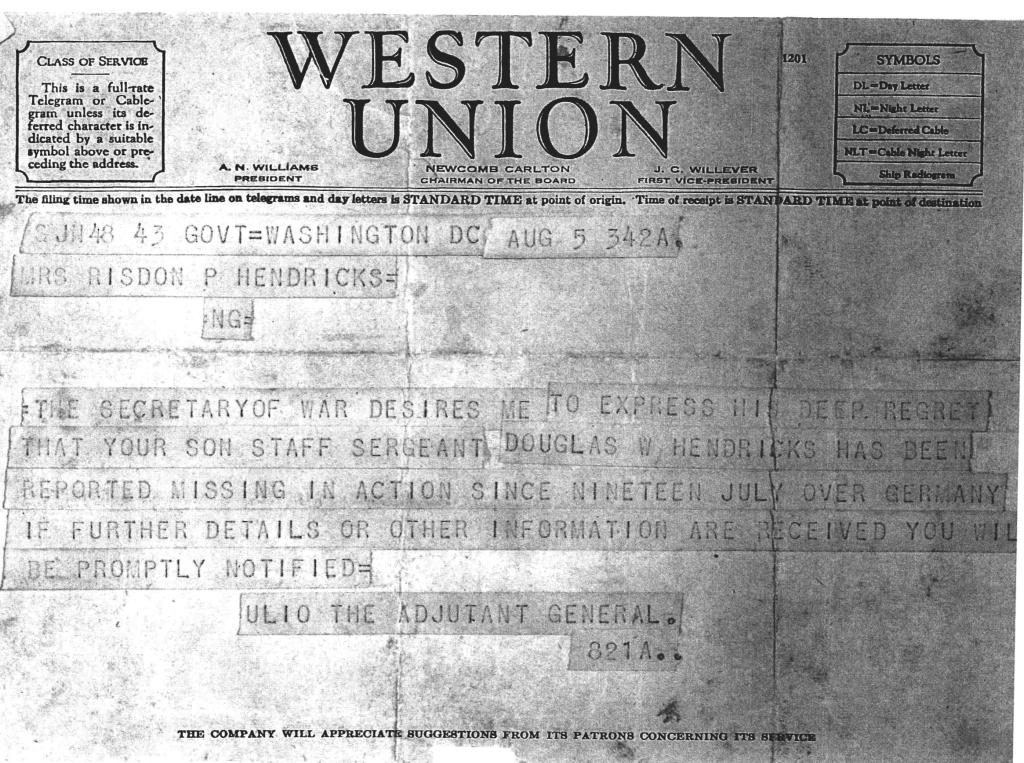

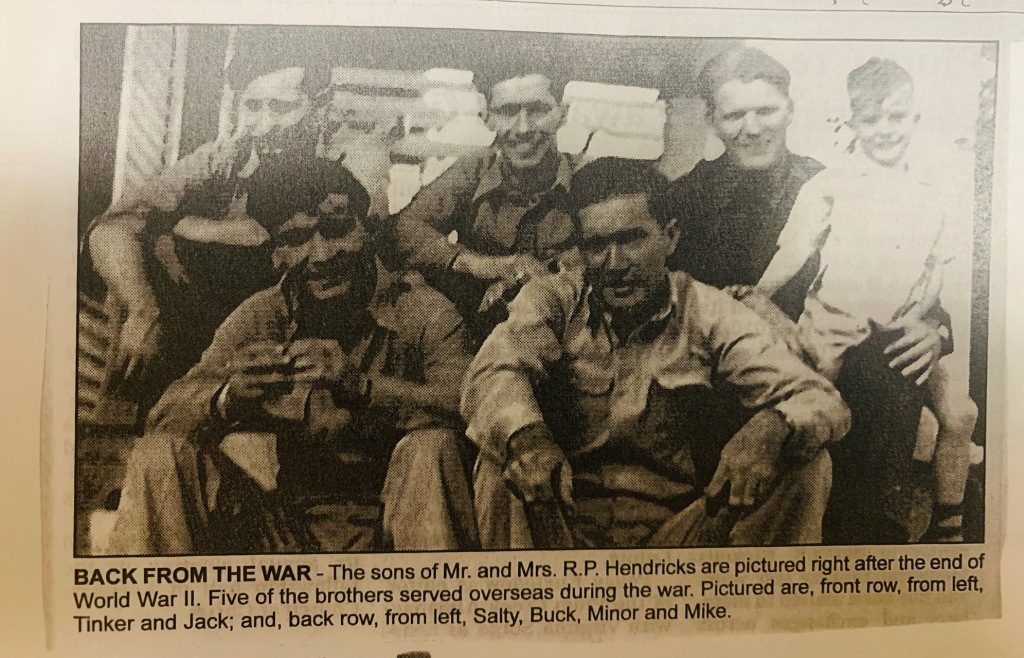

14. Luling Newsboy – Owner/Ray Bailey Sr. Editors/managers – Ray Bailey Sr., and Ray Bailey Jr. until 1975, then Bob McVey until 1978. Started by Ray E. Bailey, Sr. in 1940, this was a robust newspaper whose owner/editor had a strong sense of duty to men and women in the military. His publication, Our Men and Women in World War II reflects a monumental effort at honoring those in uniform, and is a priceless research tool.[30] Central Texas Newspapers purchased the Newsboy in 1975, and Bob McVey became editor. 15. Luling Newsboy and Signal – 1978- present. Editor- Bob McVey (1978-1981), Karen McCrary (1981-2018), Dayton Gonzales (2018 to present). Owner/publisher – Buddy Prouss. In 1978, the Signal and Newsboy consolidated. Luling Publishing Company, Inc. continued McVey as publisher/editor. The Luling Newsboy and Signal continues in publication. 16. Luling Record/Lockhart Record – 1898-? Editor – Professor Melliff. The only mention of these publications were found in an 1898 comment in a Houston newspaper: “Lockhart, Texas, May 12. – the populists of Caldwell county have purchased the plant of the Luling Record and moved it to Lockhart, where they will immediately commence the publication of a weekly newspaper. The new paper will make its advent in about ten days, and will be under the editorial management of Prof. Melliff, a thoroughly competent and experienced newspaper man.”[31] No copy has been located. 17. El Popular – Lockhart, Texas, circa 1901. Editor – Miguel Valdez. The Houston Post mentions this is as a Spanish language newspaper.[32] No copy has been found. 18. El Globo – Lockhart, Texas, circa 1893. Editor – unknown. The only mention of this publication was found in the Galveston Daily News.[33] It is possible that El Globo is mentioned in the Brenham Daily Banner of 1893: “Four newspapers, one Spanish and three American, are now published at Lockhart.”[34 19. Lockhart New Test, 1893-1897. Editor – Henry Clay Gray. An African-American graduate of Fisk University (1883) and Oberlin (1885), he created the New Test in 1893. Gray drew the wrath of William Cowper Brann, publisher of the Iconoclast, mainly because Gray was black and educated.[35] Brann was a highly controversial figure, attacking those in authority, the Catholic Church, and Baylor University. Brann was killed in a Waco gunfight with an irate Baylor supporter in 1898.[36] it is possible that the New Test was published, at least for a time, in Seguin.[37] The Galveston Daily News quoted the New Test several times in its ‘Texas Newspaper Comments’ section between 1895 and 1897. As one would expect, Gray was a Republican. He appears to have been heavily involved with the party. The Galveston Daily News reported that on January 21, 1896, “Twenty-one leading colored republicans from various portions of the state met here to-day in secret conclave to decide on a candidate for president….Among the colored leaders present were… Henry Clay Gray…”[38] On February 29, 1896, Caldwell County Republicans met at the Courthouse to elect delegates to the state and congressional conventions. Henry Clay Gray was elected as a delegate to the Ninth District, which was to meet in Austin on March 5.[39] The African American Republicans were fighting a losing battle against Jim Crow. If there is any doubt as to the personal dangers attendant with bucking white Democrats, consider this: At that same Caldwell County meeting, J.W. Larremore was elected secretary. On August 4, 1904, Larremore, “a negro school teacher and a prominent local republican politician,” was murdered outside his home in Lockhart by “unknown assailants.” His friend and fellow Republican, Tom Caperton, was severely beaten.[40] I have little doubt that Gray’s publication walked a tight line to avoid, if it did, the Southern white backlash after Reconstruction. One example of this careful balance: We do not pretend to indorse or defend the many monkey capers that have been cut up in Texas for more than a month in the name of republicanism, but the great principles of the party and the great statesmen who formulated them we do indorse, now and forever; but they have nothing to do with the monkey shines we are having in Texas.[41] During the 1890s, the Populists appealed to African-American Republicans in rallying for economic causes that crossed racial lines. Gray’s position on national and state affairs were cited by other papers. Gray was quoted as saying that “[s]pending time and money trying to land McKinley electors in Texas this year is like fishing for whales in a wash tub, with pin hooks.”[42] The Austin Weekly Statesman mentioned New Test’s political leanings during the 1896 Presidential campaign: “The republicans of Caldwell county heartily approve of your mention of dealing with mercenary so-called republicans. Old Caldwell county is going to work to roll up a big vote for McKinley, Makemson and protection.”[43] (Judge Makemson, ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1894 on the Republican ticket).[44] Too soon, the New Test’s run was over. The Lockhart Register of July 10, 1897, in a small article, stated that the New Test had been sold to Mr. Bob Palmer, “who will remove it to Buda.” On July, 17, 1897 the Galveston Daily News reported that Palmer and W.C. Carter “have purchased the New Test printing outfit and moved it to Buda and will commence next week to publish the Buda Echo….In politics it is understood it will be democratic.”[45] Gray continued in politics and as an orator. The first African-American State Fair was held in Houston in August 1896. “Mental culture,” embracing “evidences of journalism, poetry, prose and song” was one of the many topics meant “to show the world the remarkable and unprecedented advancement of the southern negro (especially in Texas) since they merged [sic] from the darkness of slavery into the light of freedom.”[46] No copy has been found of this weekly, nor has any further information been found on Henry Gray. 20. The Colored Citizen, Lockhart, Texas, 1907-1908. Editor – Percy Tucker. Tucker apparently was a schoolteacher. An African-American publication. No copy has been found. 21. Lockhart Express, 1853-? Publisher – J. Hubbard Stuart and Company; Editor – Mary E. Stuart [Stewart?]. In its November 5, 1853 edition, the Gonzales Inquirer stated that “[I]t appears that our friends of Lockhart will have a paper. Mr. Stewart [Stuart?], of the “celebrated Lavaca Express,” paid us another visit a few days since and he states that he has made the necessary arrangements to commence its publication in that town at an early day. We believe he designs calling it The Lockhart Express. May you meet with ample success, Stewart.”[47] A month later, the Gonzales Inquirer noted: “The “Express” is a neat little sheet, and being the only one in the State edited by a lady, is entitled, and doubtless will, receive a hearty support.”[48] The Nacogdoches Chronicle stated: “It must not be supposed that because a woman writes for the ‘Express,’ it is a ‘woman’s rights’ paper, for we see no indication of the kind.”[49] No copy has been found, nor has any information been found on Mary Stuart. She possibly was the wife of the paper’s owner. It is possible that Mrs. Stewart is the same person referenced in a 1936 article in the Lockhart-Post Register as the publisher of the Mirror. The authors of the 1936 article state:

The first newspaper in Caldwell [sic] was “The Mirror,” a small weekly which was published by Mrs. Isabel Stewart. She not only conducted editorial department, but she worked in the mechanical department. After a struggle of about one year in a vain effort to maintain “The Mirror,” Mrs. Stewart yielded to the inevitable and removed her printing office to San Diego, California, where she published a paper for several years.[50]

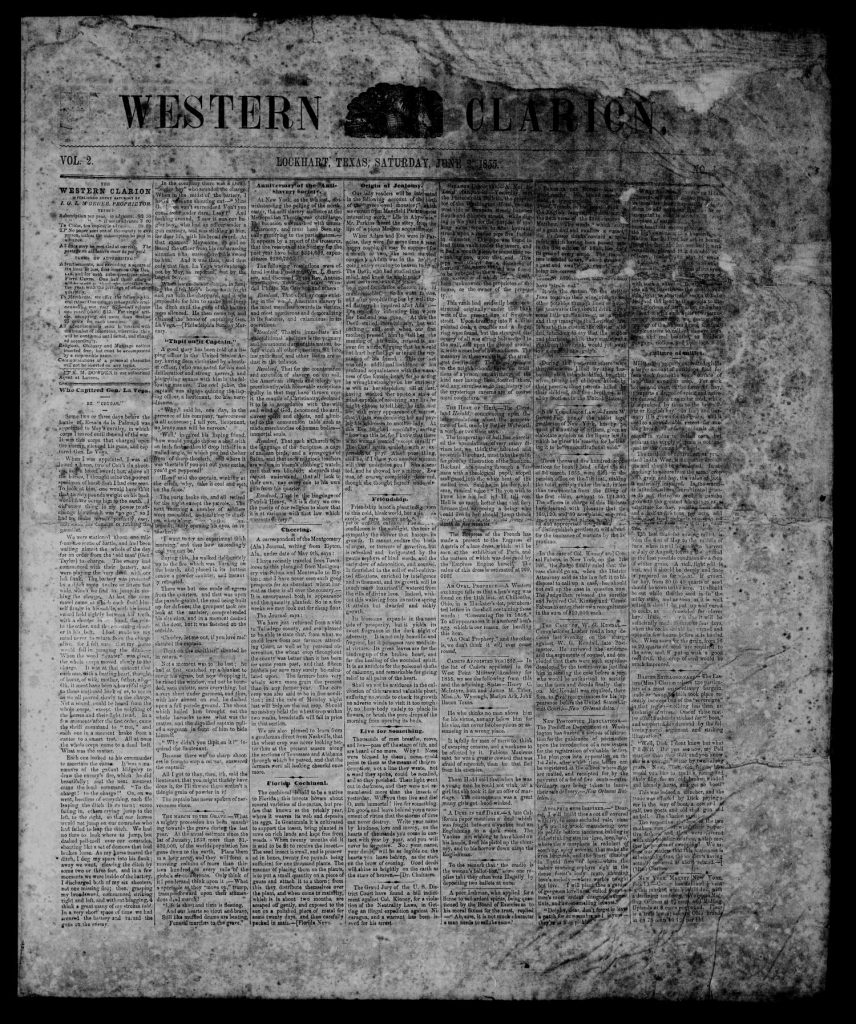

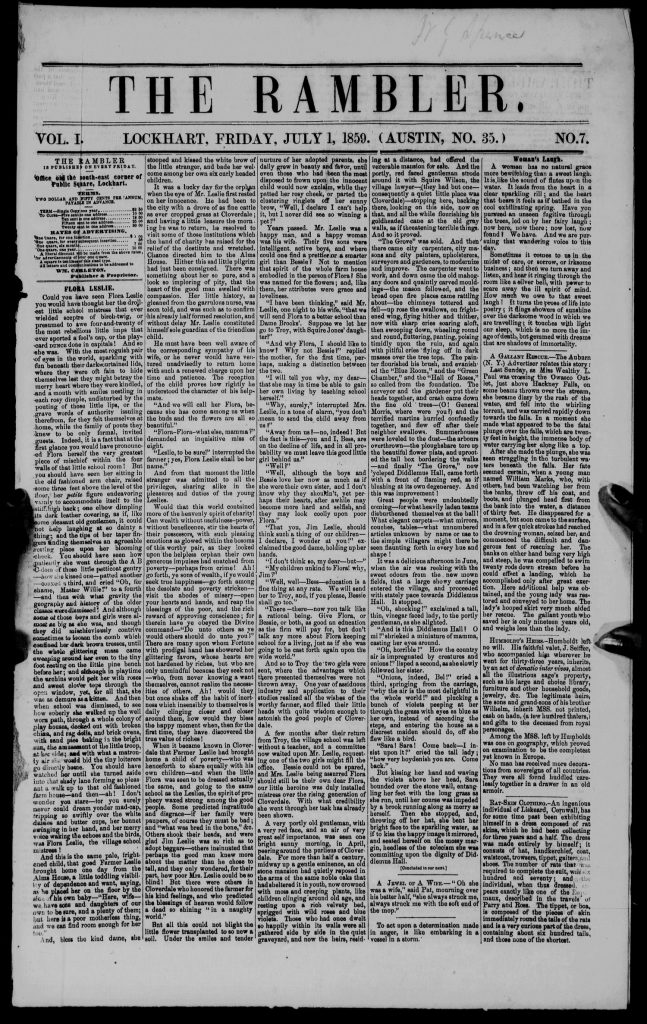

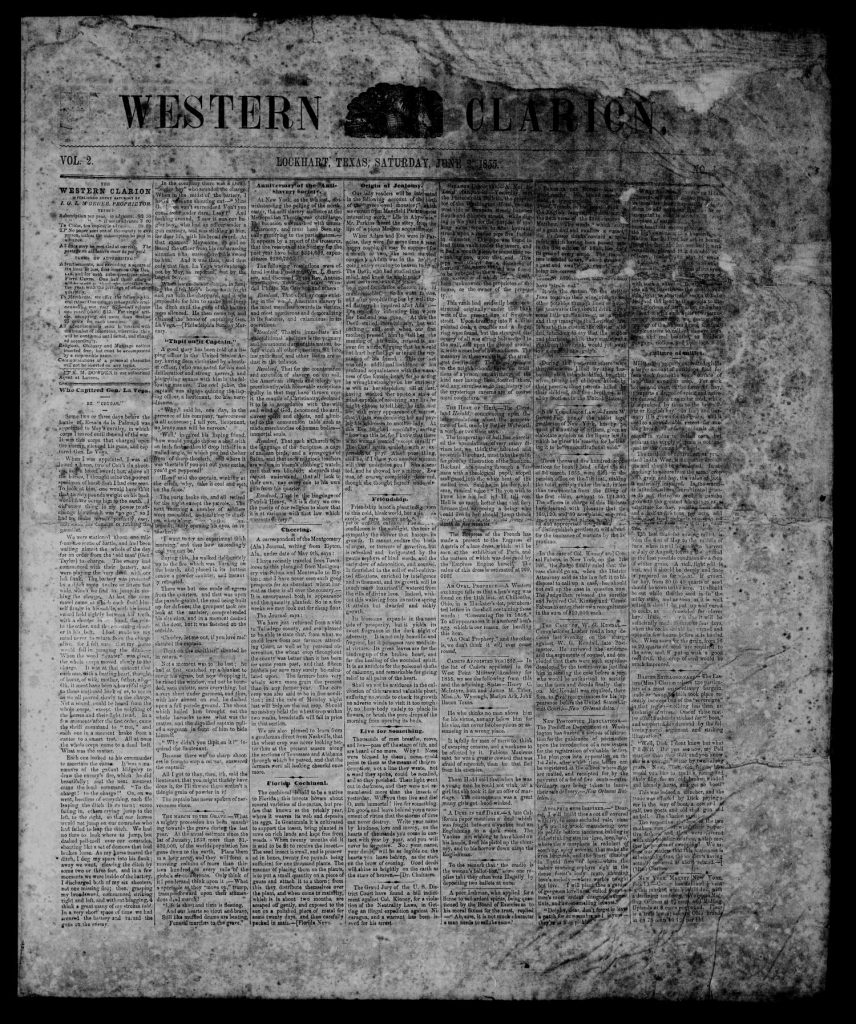

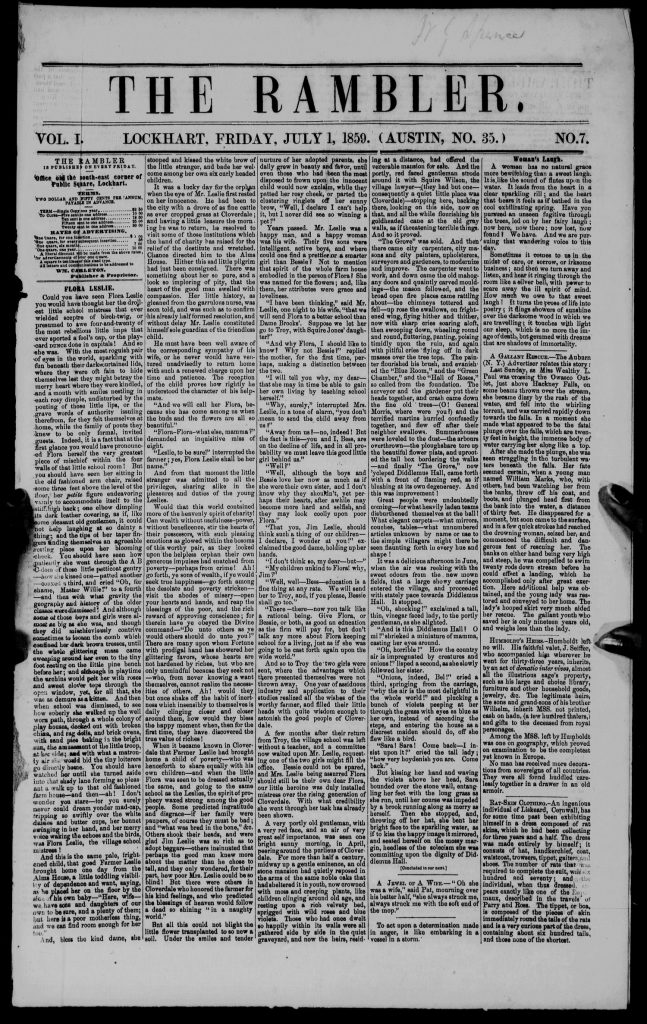

22. Western Clarion, Lockhart, Texas, circa 1855. Publisher – I.G.L. McGehee. Little is know about this publication. The front page of its June 2, 1855 edition shows an impressive effort made at gathering ‘hard’ news. Its editor reported, without negative comment, on an anniversary gathering in New York City of William Garrison’s Anti-Slavery Society, printing the Society’s resolutions condemning the practice of slavery. 23. Lockhart Guard – possibly 1850s. Publishers – Colonel John M. Crane and Atticus Ryman. “’The Guard’” ran for only a few months. According to an article in the Lockhart Post-Register’s Centennial Edition in 1936, the editor had to quit printing it because he criticized the lawlessness and the gamblers in the county. The gamblers and horse thieves told him that they would run him out of town if he didn’t stop publishing this paper. He moved to Goliad and published ‘The Goliad Guard.’”[51] 24. Lockhart Rambler, circa 1859. Publisher – William Carleton. The Texas State Gazette (Austin, Texas) stated: “We learn that Mr. Carleton has removed the Rambler to Lockhart. We shall be very glad to hear of his success in that enterprising town.”[52] It appears that, while the office was located on the southeast corner of the town square, the paper’s printing continued in Austin. The Weekly Telegraph (Houston, Texas) referenced a story in The Rambler, which told of the tragic death of a seven year old boy living near Elm Creek. While playing with a horse, the child’s hand became entangled in the animal’s stake rope. The horse spooked, tearing the child’s hand off.[53] Carleton, a native of England, fought in the Texas Revolution with Philip Dimmitt’s company and was at the capture of Goliad in December 1835. He died on November 11, 1875 at the age of fifty-three.[54] A story in the Centennial Edition of the Lockhart Post- Register tells of an incident involving Mr. Carleton. Unfortunately, as seen below, it states that Carleton started the Clarion (or Western Clarion), which is incorrect. Nonetheless, if true, it speaks of the dangers of being a journalist on the frontier:

23. Lockhart Guard – possibly 1850s. Publishers – Colonel John M. Crane and Atticus Ryman. “’The Guard’” ran for only a few months. According to an article in the Lockhart Post-Register’s Centennial Edition in 1936, the editor had to quit printing it because he criticized the lawlessness and the gamblers in the county. The gamblers and horse thieves told him that they would run him out of town if he didn’t stop publishing this paper. He moved to Goliad and published ‘The Goliad Guard.’”[51] 24. Lockhart Rambler, circa 1859. Publisher – William Carleton. The Texas State Gazette (Austin, Texas) stated: “We learn that Mr. Carleton has removed the Rambler to Lockhart. We shall be very glad to hear of his success in that enterprising town.”[52] It appears that, while the office was located on the southeast corner of the town square, the paper’s printing continued in Austin. The Weekly Telegraph (Houston, Texas) referenced a story in The Rambler, which told of the tragic death of a seven year old boy living near Elm Creek. While playing with a horse, the child’s hand became entangled in the animal’s stake rope. The horse spooked, tearing the child’s hand off.[53] Carleton, a native of England, fought in the Texas Revolution with Philip Dimmitt’s company and was at the capture of Goliad in December 1835. He died on November 11, 1875 at the age of fifty-three.[54] A story in the Centennial Edition of the Lockhart Post- Register tells of an incident involving Mr. Carleton. Unfortunately, as seen below, it states that Carleton started the Clarion (or Western Clarion), which is incorrect. Nonetheless, if true, it speaks of the dangers of being a journalist on the frontier:

William Carleton, an Englishman, established “The Clarion” [sic], but it didn’t stay in existence long because of a little incident. One night at supper table at his boarding house a drunk man by the name of Compton, who was a carpenter and cabinet maker, got mad at some joking remark Carleton made. Without a word of warning he attacked Carleton and disabled him temporarily. This caused a suspension of the paper, and its publication was never resumed.[55]

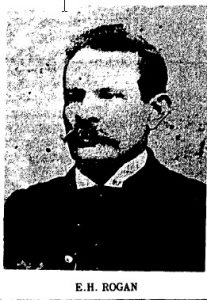

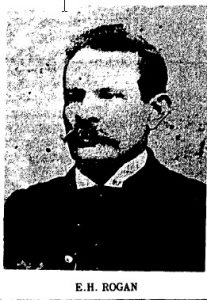

- Southern Watchman, 1857-? Publisher – E.H. Rogan. Austin’s Southern Intelligencer informed its readers in 1860 that “E.H. Rogan has started a new paper in Lockhart, called the ‘Texas Watchman.” The first number promises well for success.”[56] As seen below, The Southern Watchman existed at least since 1857. I suspect that newspaper originated in Austin, and perhaps

moved its offices to Lockhart in 1860. Proudly proclaiming that “We Stand by the Constitution,” its June 6, 1857 edition told of an ill-fated American filibuster into Mexican Sonora.[57]

moved its offices to Lockhart in 1860. Proudly proclaiming that “We Stand by the Constitution,” its June 6, 1857 edition told of an ill-fated American filibuster into Mexican Sonora.[57]

- South and West, 1865-? Publishers – Edgar H. Rogan and J.D. Buchanan. The newspaper’s publishers stated it would be “published simultaneously at Austin and Lockhart, Caldwell County.” It’s inaugural edition, dated Tuesday, December 19, 1865 listed its owners’ many aims. “To attempt, however feebly, to heal the wounds of our beloved—our native land, must, it appears, be the immediate duty of all. Pursuant to this view, every effort shall be made, by South and West, to develop; to utilize, and to mature, all our varied resources; the arts of mining, manufacturing, and husbandry.”[58]

- The Plow Boy, 1868-? Publishers – N.C. Raymond and E. H. Rogan. It was originally published in Austin. Raymond’s partner and the paper’s printer, withdrew from the partnership, although continuing to set type.[59] In May 1869, the operation moved to Lockhart. “We have received the May number of the Plow Boy, published at Austin, Texas, by our old friend Nat. Raymond, [wrote the Dallas Herald] – On or about the 1st of June, we understand the Plow Boy is to be published weekly. – Mr. Raymond has associated with him Mr. M.E.H. Rogan, of Lockhart, Caldwell County, at which place the paper will be hereafter published….Raymond can and will make a first-rate paper, and we will be glad to see him successful.”[60] The 1870 American Newspaper Directory listed the Plow Boy (its motto was “Disconnected with Partisan Politics”) as the only newspaper in Lockhart ‘devoted to agriculture.’ Apparently, the Directory’s publisher, Geo. P. Rowell & Co., printed circulation figures provided by the newspapers themselves. The Plow Boy claimed 1000 as its circulation.[61] Using 1869 or 1870 information, the 1871 Texas Almanac’s only listing for a newspaper in Lockhart was the Plow Boy.[62] In all likelihood, this figure was substantially inflated. Raymond was something of a renaissance man. In 1857, the Texas State Times reported on Raymond’s house, then in construction, a mile from the Capitol: “The outer walls of the building are eighteen inches thick, and composed of a new material, prepared from the common soil of the country, of which Mr. Raymond claims to be the discoverer. We have no pretensions to nice artistic skill and judgment in the mechanical arts; but from the appearance of solidity and durability in these walls, we should at once pronounce them to be equally as substantial as edifices of stone or burnt brick. The idea of converting, by chemical agencies, any kind of clay or soil into a valuable material for building and fencing purposes, by a simple and cheap process of preparation, is certainly an original and bold conception. None but a mind confident in the resources of its own genius would have persevered in the attainment of its ends….” [63] In 1858, Raymond applied for and was granted a U.S. Patent on a type of composition building material that contained, among other things, charcoal and cow dung.[64] It appears the Plow Boy folded upon the death of N.C. Raymond. The January 5, 1871 edition of the Houston Telegraph, quoting the State Journal, gave an account of Raymond’s demise:

Mr. Raymond, who has been conducting an agricultural journal at Lockhart, started for Austin to spend Christmas with his family. On arriving at Onion creek, about eight or nine miles from home, it being late in the afternoon and very cold weather, with a sharp north wind, Mr. Raymond complained of cold and alighted to walk with the buggy drove on to the house where he was to stop for the night. An hour elapsed, and his non-arrival causing alarm, he was sought for and found dead in the road but a few paces from the place where he alighted. His death was caused by an attack of neuralgia of the heart, and was probably instantaneous.[65]

Nathaniel Charles Raymond died on December 22, 1870. He was fifty-one years old. He is buried in the Oakwood Cemetery in Austin. His wife, Lucinda, died in 1882.

- The Texas Digest, 1870 – ? Editor- W.D. Cary. Mentioned in another publication, little is known about this newspaper. [Illegible source] stated: “And yet another Republican journal has unfurled its banner to the breezes of republican freedom and equal rights in Texas. “The Texas Digest,” published in Lockhart, Caldwell county, and edited by W.D. Cary, reached us last evening. It is not very large, but large enough, and it is exceedingly well edited for the first number. The editorials are ably written, and in excellent spirit. We cordially welcome our new fellow laborer into the ranks of Republican journalism.”[66]

- Lockhart Advocate – circa 1898. Editor – unknown. The only mention of the publication is in 1898. The Dallas Southern Mercury, quoting another newspaper, the Dublin Progress, reported: “’The Lockhart Advocate has been consolidated with the Gonzales Drag Net and the latter has been increased in size from four to eight pages. The Drag Net is one of the ablest Populist papers in Texas and it is meeting with deserved success. Both the Progress and the Drag Net are excellent papers.”[67]

- Lockhart Phonograph – 1893- ?. Owner and Publisher – Horace Bruce Roberts. This newspaper is mentioned in several contemporary publications, but no copy has been located. The 1894 American Newspaper Directory lists it, along with the Lockhart Register:

[68]

The Dallas Morning News, publishing reports from other Texas newspapers in a section entitled The State Press, quotes an individual named Palmer (possibly its editor): “The State Press Association met at Dallas this week, which gave editors who have apron strings around their necks at home, an opportunity to celebrate the occasion in the usual manner, full of whiskey.” [69] Given that the owner of the Phonograph was a preacher, one wonders how long Palmer lasted. In an 1893 article on the Lockhart Lyceum the Lockhart Register stated that a debate team discussed “Should Caldwell County build a new courthouse in the city of Lockhart.” It further stated that “Mr. W.R. Parker and Bruce Roberts were added to our number and we welcome them among us.[70] According to his mother Aurilla’s obituary of 1910, the Roberts family settled in the area before Caldwell County was formed.[71] Horace Bruce Roberts was born in Lytton Springs in 1869. His newspaper lasted only a short time, and by the end of the century, Rev. Roberts had moved on. On November 24, 1899, he was back in town from Cotulla, Texas, visiting with “old friends.”[72] In the ensuing years, Reverend Roberts lived in San Antonio, where he published Baptist Word and Work,[73] Moore Station in Frio County,[74] and Dilley, Texas.[75] Roberts died at the age of eighty-nine, in Uvalde, Texas. He is buried in the Mount Hope Cemetery at Carrizo Springs.[76] 31. Lockharter Zeitung – 1901- ? Publisher – M. Hoffmeister. The influx of German speaking farmers into the county in the late 1890s and early 1900s created a perceived market for a newspaper printed in German. Unfortunately, the one known newspaper of this type appears to have lasted only about a year.[77]

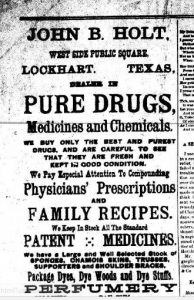

- Lockhart Courier – 1908-1010. Publisher – Carey Smith; 1910-1910 John. B. Holt. This was a slick publication, with quality photographs. Its quality may explain its short lifespan. It appears that John B. Holt, a local pharmacist with a business on the west side of the Lockhart Courthouse Square purchased or leased the Courier. Most of his copy was devoted to patent medicines he had in stock. It appears that few editions were published.

.

- Lockhart News Echo, 1872-1880? Publisher – E.H. Rogan, editor and later Hallum & Co, then J.P. Bridges, owner and publisher. Described as a ‘spicy’ newspaper by the Galveston Daily News[78], it barely survived its first few months. Rogan was also an attorney. Rogan’s business was destroyed in June 1872. Quoting

the State Gazette, the Galveston newspaper stated that “the News Echo printing establishment was destroyed by fire on Sunday night…. It is stated to be the work of an incendiary – a fiend incarnate, who should be ferreted out and brought to condign punishment…. We tender our sympathies to Captain Rogan for the loss he has sustained. The News Echo was edited with great ability, and we trust to see it at an early day rise Phenix-like [sic] from its ashes and resume publication.”[79] The News Echo did rise Phoenix-like, but without Rogan. W.K. Hallum and W.C. Bowen were identified as its owners in August 1872.[80] The banners for the publication (“The Safety of the People Is the Supreme Law,” and “The Welfare of the People Is Our Guiding Star”) seemed to proclaim the paper’s populist leanings. An 1872 edition took great glee in listing many newspaper accounts describing the corruption in the Grant administration.[81] Its editor at the time, Will F. Faris, seemed to enjoy a good fight. In 1875, the Galveston Daily News commented on this. “The Lockhart News Echo keeps up a pretty lively fight with the [Austin] Statesman. Keep cool, brothers, if you can [in] this hot weather.”[82]

the State Gazette, the Galveston newspaper stated that “the News Echo printing establishment was destroyed by fire on Sunday night…. It is stated to be the work of an incendiary – a fiend incarnate, who should be ferreted out and brought to condign punishment…. We tender our sympathies to Captain Rogan for the loss he has sustained. The News Echo was edited with great ability, and we trust to see it at an early day rise Phenix-like [sic] from its ashes and resume publication.”[79] The News Echo did rise Phoenix-like, but without Rogan. W.K. Hallum and W.C. Bowen were identified as its owners in August 1872.[80] The banners for the publication (“The Safety of the People Is the Supreme Law,” and “The Welfare of the People Is Our Guiding Star”) seemed to proclaim the paper’s populist leanings. An 1872 edition took great glee in listing many newspaper accounts describing the corruption in the Grant administration.[81] Its editor at the time, Will F. Faris, seemed to enjoy a good fight. In 1875, the Galveston Daily News commented on this. “The Lockhart News Echo keeps up a pretty lively fight with the [Austin] Statesman. Keep cool, brothers, if you can [in] this hot weather.”[82]

Ownership changed several times over the years. J. P. Bridges became publisher in 1878.[83] He would later relinquish the Lockhart paper and buy the Luling Signal, which he would publish until his death in 1893.[84] Brenham’s Weekly Banner of May 28, 1880 had a small story regarding the New-Echo’s ownership: “W.R. McDaniel has retired from the Lockhart News-Echo and W.B. Smith, an ambitious and rising young lawyer will [?] Echo-News to the people of Lockhart and Caldwell County.”[85]

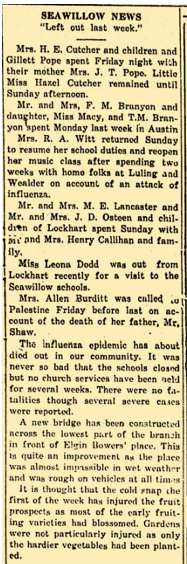

- Caldwell County Register / Lockhart Register – circa 1880 – 1908. Publisher and editor – several. After purchasing the News-Echo, Smith, a transplanted Kentuckian, changed its name to Caldwell County Register.[86] He sold the paper in 1882 to G.M. Lassater, and returned to Kentucky. To avoid confusion with a publication in the town of Caldwell, Lassater changed the paper’s name to the Lockhart Register.[87] He may have been compelled, at least by public opinion, to do so. Brenham’s Daily Banner huffed a bit on this issue in 1880: “Texas has a number of papers of the same name, but each paper is designated by place of publication, it has two Caldwell Registers, one published in Caldwell county and the other in Caldwell town, Burleson county. The latter paper is the oldest and is entitled to the prefix Caldwell by reason of its seniority.”[88] Lassater then sold the paper to Reese Wilson. Wilson operated a newspaper in East Texas until 1885. During part of that time, B.G. Neighbors was editor and J.D. McMurtry the business manager. Reese Wilson moved to Lockhart in January 1886 and assumed control of the paper.[89] At that time, Neighbors left and purchased the Kyle News.[90] Wilson wasn’t afraid to express strong opinions about civic issues: …Wilson also criticized the opinions and actions of other editors. Through satire and repeated criticism in print, he goaded town and county officials to action…Official laxness of duty or slowness in advancing a civil project always called forth editorial criticism by Wilson. He attacked the filth caused by keeping pigs in the city and brough about changes. He also argued for hitching racks (so the horses would not road the streets freely while their owners were inside business places and stores), water troughs, electric lights, and a water and sewer system. Wilson also campaigned – successfully—for an Opera house in Lockhart.[91 In failing health, Wilson sold the Lockhart Register in 1908 to George Baker who then leased it to some prohibitionists. When their lease expired, the Lockhart Register was leased to anti-prohibitionists, with Luther Hurst as it editor. When Caldwell County went dry, H.E. Cutcher became the editor.

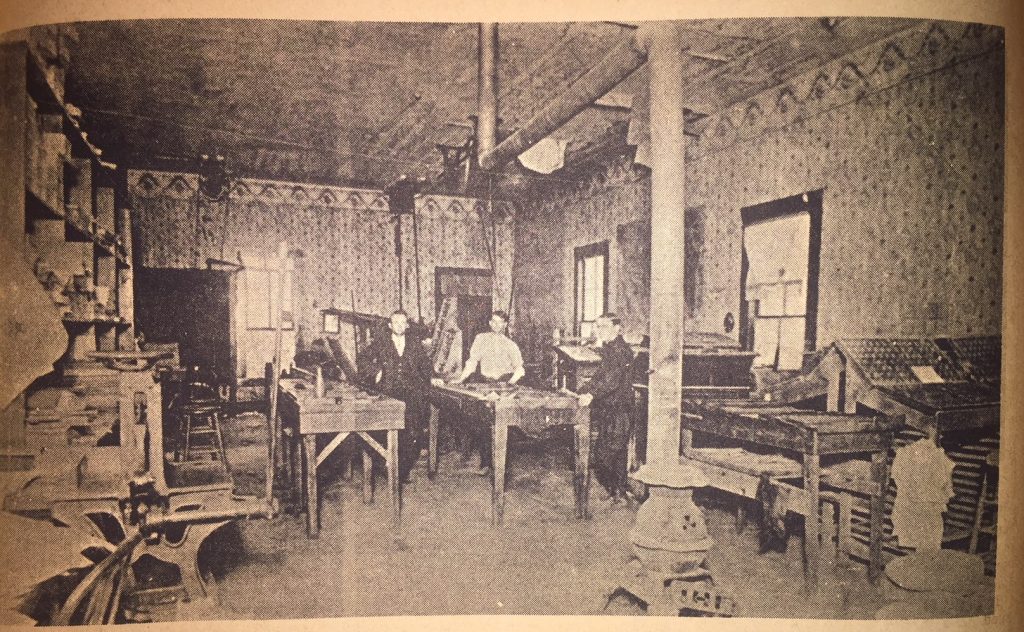

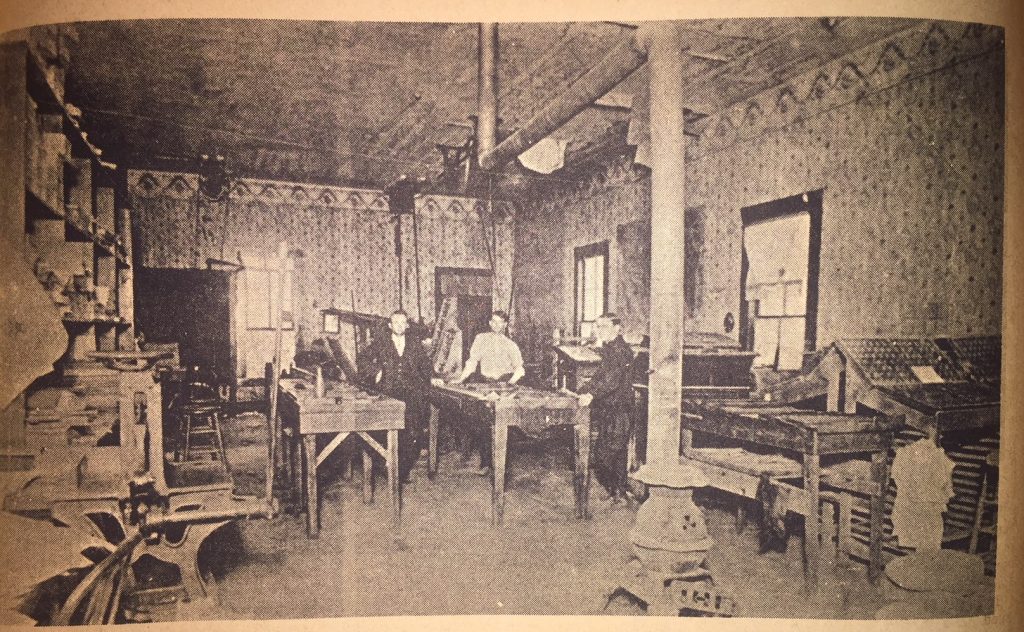

Pressroom, Lockhart Register, Early 1900s

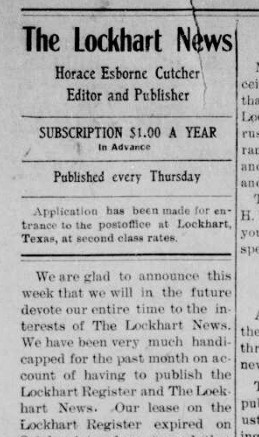

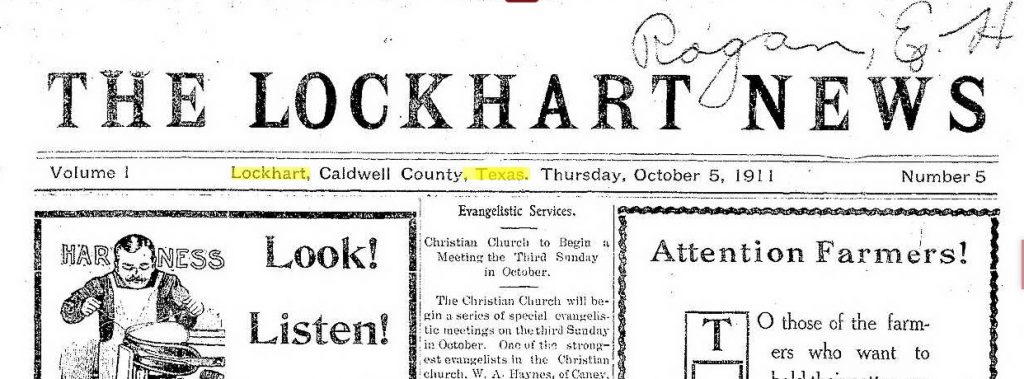

- Lockhart News – 1910- ? Owners/publishers -A.M. Jordan, and Vance Smith. Editor – H. E. Cutcher. The News purchased the defunct Courier plant and began publication.[92] Cutcher left the Lockhart Register to devote his time to the Lockhart News. A.W. Jordan’s involvement appears to have been limited. Almost as soon as the News made its appearance, Jordan, a mail clerk on the Lockhart-Yoakum run of the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad, purchased the Love County (Oklahoma) News. Jordan’s reason for leaving the Courier, where he had been city editor, was his inability to give enough time to that project. He continued as a railway mail after purchasing the Oklahoma newspaper.[93]

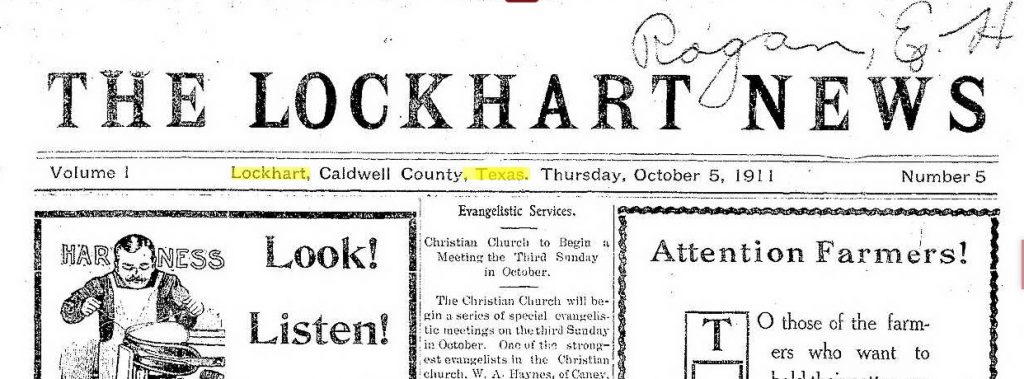

- Lockhart Post (Lockhart Weekly Post) – 1899 – 1915. Editors and publishers, Lay and Carey Smith (1899-1906), then W.M. Schofield and Bob Andrews (1906-1915) and Stanley and J. Louis Mohle, Sr. (1913-1915). The Smiths’ “polished prose and literary writing” won it much praise.[94] Its finances were shaky, and in 1906 the paper was sold to Schofield and Andrews. Schofield was “once principal of the Lockhart public schools, and Mr. Andrews has been for years the foreman of the Lockhart Register.”[95] The two later brought in Stanley and Louis Mohle, Sr. Schofield, a strong anti-prohibitionist did most of the writing until 1913.[96]

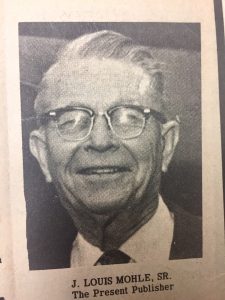

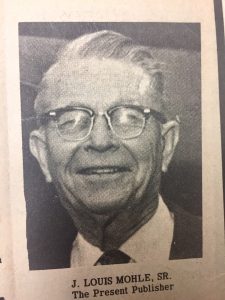

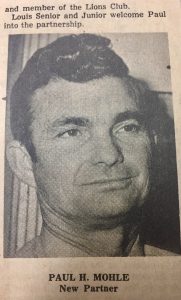

- Lockhart Post-Register – 1915-present. Owners and publishers – Andrews, Schofield, Stanley Mohle, Louis Mohle, Sr. (1915-1928); Schofield, Stanley Mohle, and Louis Mohle, Sr. (1929-1940); Stanley Mohle and Louis Mohle, Sr. (1940-1948): Stanley Mohle, Louis Mohle, Sr. and Louis Mohle, Jr. (1948-1958); Louis Mohle, Sr. and Louis Mohle, Jr. (1958-1972); Louis Mohle, Sr., Louis Mohle, Jr. and Paul Mohle (1972-1979); Floyd Garrett (1979-1989); 1989- present, Dana and Terri Garrett. The Post and the Register merged in 1915.[97] Financially, Lockhart couldn’t support two competing newspapers. The Mohle family acquired full ownership of the Post-Register, and Louis Jr. took over the editing duties from his father. Paul joined the newspaper in 1960, and purchased an interest in 1972. The Mohles sold the newspaper in 1979. During their ownership, the Post-Register won several awards from the Texas Press Association. Floyd Garrett’s son Dana became the newspaper’s publisher in 1979. He and his wife Terri acquired the newspaper in 1989. It continues as Lockhart’s only newspaper. A weekly, with Thursday publication date, its current editor is Miles Smith.

Co-owner Dana Garrett

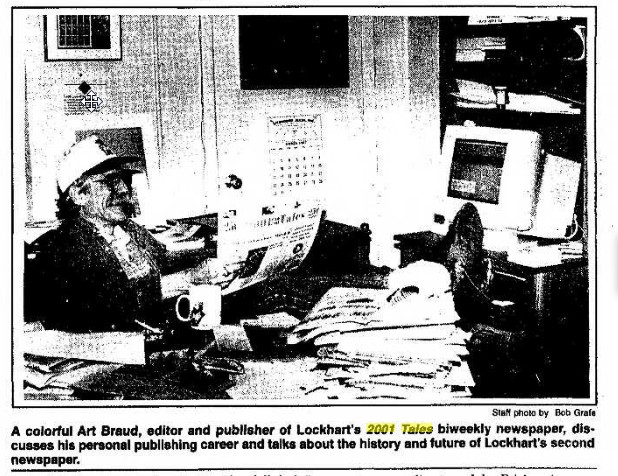

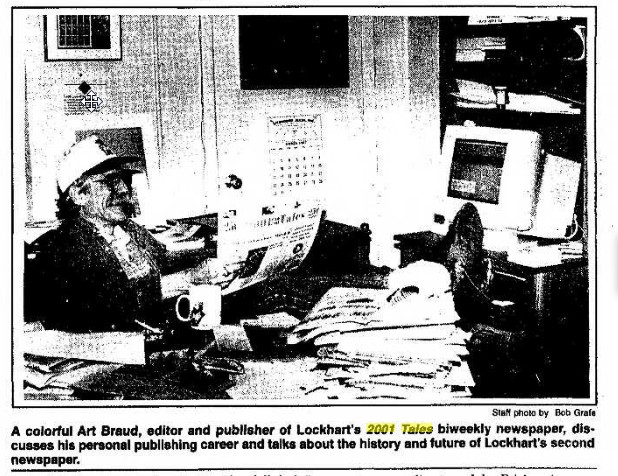

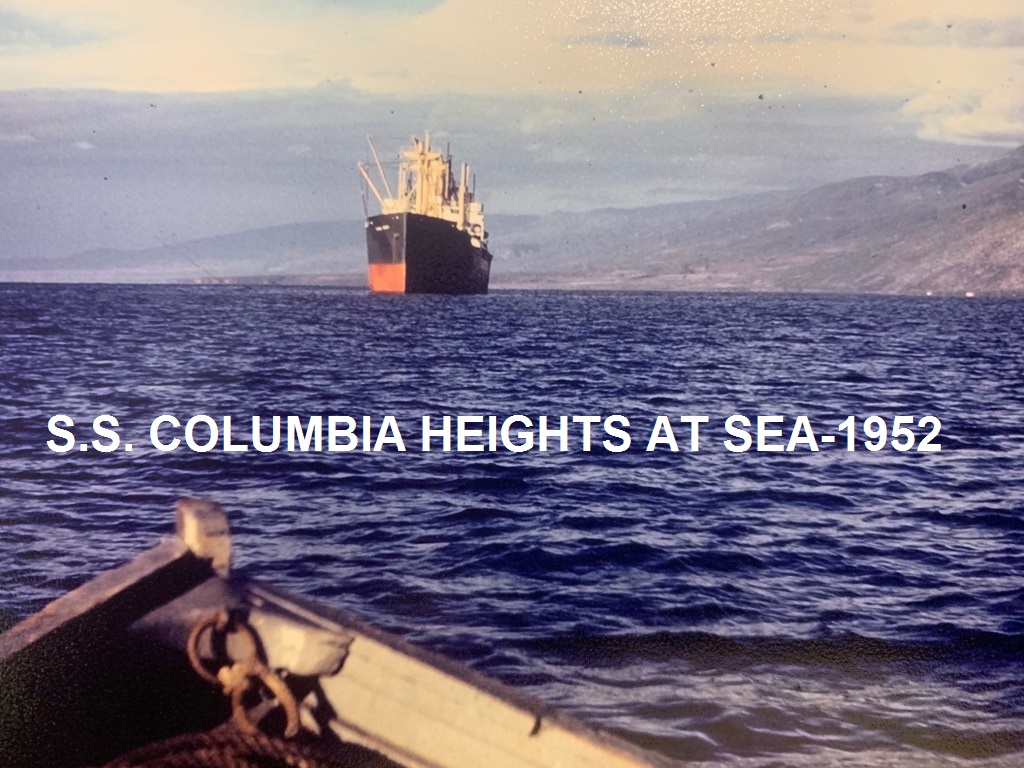

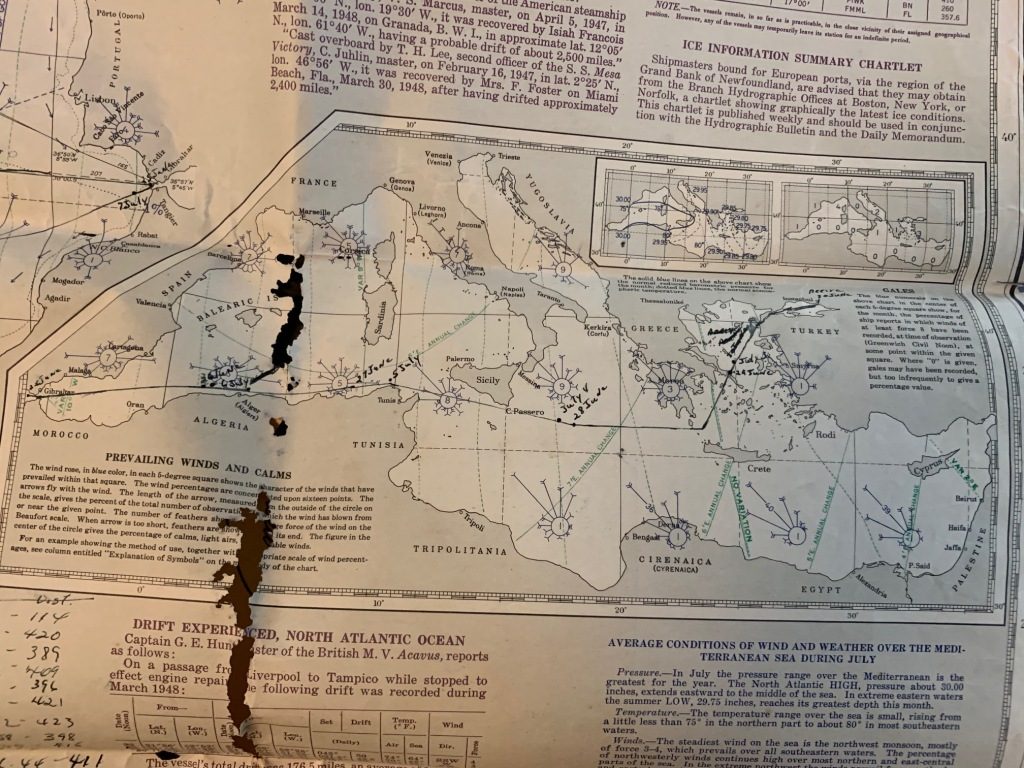

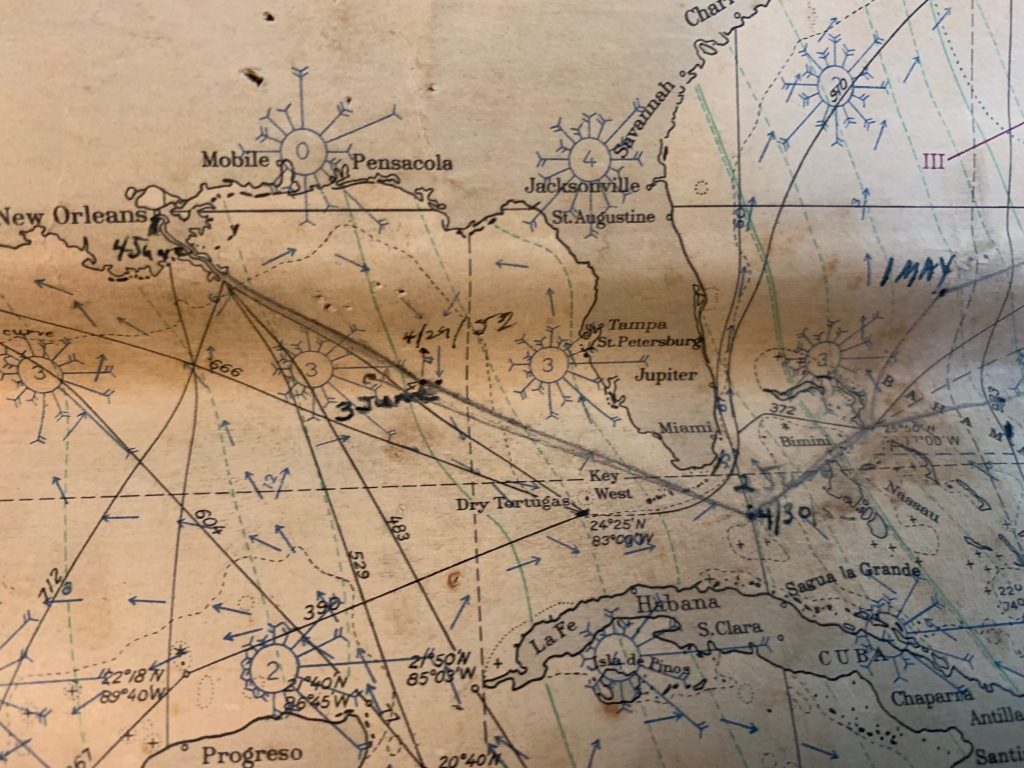

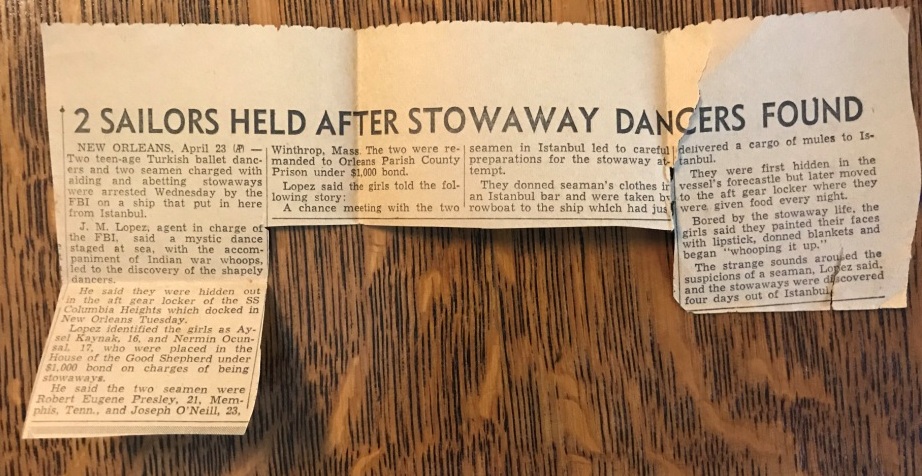

- 2001 Tales – 1992? – 2000? (Lockhart) Publisher – Sue King, and from 1993 on – Arthur “Art” Braud. Braud obtained 2001 Tales from King. Under her, the paper only had forty-eight issues before failing. Braud, a colorful ex- merchant marine who had lost an eye, published 2001 Tales on a bi-weekly basis.[98] With an office on Market Street, Braud converted the mimeographed/copied flyer into a legitimate newspaper. “I had a good time. I used newsboys to sell it on the streets a few times. I used a linguist whom I paid fifty dollars per edition to proof it, and had a legally blind receptionist.”[99] It appears that the publication’s name was changed to 2001 Plum Creek Tales some time around 1997.[100] The publication occasionally billed Caldwell County for legal notices. Braud closed the business down in 1998.

- Caldwell County Citizen – 1984-1989. Editor – Willis Webb, and later Don Werlinger. Little can be found of this short-lived periodical. Don Werlinger, who at one time owned and operated the local AM radio station KCLT, apparently purchased a small periodical and attempted to get a newspaper off the ground to compete with the Post Register. In 1984, former Post-Register publisher Willis Webb along with Jerry Thames, sued Werlinger and two other individuals. The suit alleged that Webb and Thames had extended credit to Byron and Carolyn Tumlinson, with the understanding that the two would operate the newspaper, and that the profits would be split. Werlinger was alleged to have bought the Tumlinsons’ interest, freezing out Webb and Thames. In the meantime, the suit alleged substantial bank overdrafts.[101] Werlinger represented to the Caldwell County Commissioners Court that the newspaper had enough circulation to qualify for county legal notice dollars, which was strongly disputed by some. Although it did receive some county business, the publication did not survive. 40. Lockhart Times-Sentinel – 2004-2006. Greg Hardin, publisher and editor. After leaving the Post-Register, Hardin, who had been the paper’s editor, started the Times-Sentinel. It lasted less than two years. Hardin then attempted to continue the effort as an internet publication. That too failed. No copy has been located.

There are three other publications not included in any depth in this story. They are the Lockhart Guard, the Baptist Visitor, and the South Texas Baptist, all purportedly printed or published in Lockhart. Other that brief mention, nothing has discovered regarding their existence. I have little doubt that there may have been other newspapers that existed briefly. Only in recent years have attempts been made to preserve newsprint in digital form. Sadly, some outstanding writing, excellent reporting, and brilliant opinion pieces have been lost.

ENDNOTES

1 Historical Sketch of Martindale by T.A. Buckner, circa 1925.

[2] San Antonio Express (San Antonio, Texas), Vol. 34, No. 288, November 5, 1899.

[3] Lockhart Weekly Post (Lockhart, Texas), Vol. III, No. 87, September 19, 1901.

[4] Historical Sketch of Martindale by T.A. Buckner, circa 1925.

[5] National Newspaper Directory and Gazeteer by Pettingill, 1903.

[6] Brenham Weekly Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 13, No. 5, Ed. 1, February 1, 1878.

[7] Denison Daily News (Denison, Texas), Vol. 5, No. 283, Ed. 1, January 29, 1878.

[8] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 55, No. 178, ed. 1, September 18, 1896.

[9] Luling Evening Augur (Luling, Texas), Vol. 1, No. 80, August 8, 1884.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 41, No. 223, Ed. 1, December 7, 1882.

[12] Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Texas), June 22, 1935, referencing June 22, 1885 issue of the Dallas Herald.

[13] Forth Worth Gazette (Ft. Worth, Texas), Vol. 15, No. 191, Ed. 1, April 24, 1891.

[14] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 49, No. 7, Ed. 1, May 4, 1890.

[15] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 49, No 150, Ed. 1, September 26, 1890.

[16] Ft. Worth Gazette (Ft. Worth, Texas), Vol. 13, No. 25, Ed. 1, May 28, 1891.

[17] La Grange Journal (La Grange, Texas), Vol. No. 51, Ed. 1, December 21, 1893.

[18] Brenham Daily Banner (Brenham, Texas), August 10, 1901.

[19] Lockhart Weekly Post (Lockhart, Texas), Vol. V, No. ?, February 5, 1903.

[20] Bastrop Advertiser (Bastrop, Texas), Vol. 49, No. 48, Ed. 1, December 6, 1902.

[21] Luling Newsboy & Signal (Luling, Texas), July 26, 2012.

[22] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 36, No. 255, Ed. 1, January 15, 1878.

[23] Brenham Daily Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 8, No. 210, Ed. 1, September 2, 1883, quoting the LaGrange Journal (LaGrange, Texas).

[24] Weekly Democratic Statesman (Austin, Texas), Vol. 7, No. 15, Ed.1, January 17, 1878.

[25] The Daily Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 5, No. 299, December 8, 1880.

[26] San Marcos Free Press (San Marcos, Texas), Vol. 11, No. 46, Ed. 1, October 12, 1882.

[27] Brenham Daily Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 10, No. 265, Ed.1, October 28, 1885.

[28] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 50, No. 173, Ed. 1, September 13, 1891.

[29] Luling Signal & Newsboy (Luling, Texas), April 24, 2008.

[30] Our Men and Women in World War II, edited by R.E. Bailey (1944).

[31] Houston Daily Post (Houston, Texas), Vol. 14, No. 41, Ed. 1, May 13, 1898.

[32] Houston Daily Post, 17th yr., No. 244, Ed.1, December 4, 1901

[33] Galveston Daily News, Vol. 52, No.199, October 8, 1893

[34] Brenham Daily Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 18, No. 22, Ed. 1, September 16, 1893.

[35] Lone Star Travel Guide Central Texas, by Richard Zeladne, Taylor Trade Publishing 2011, p. 208

[36] Brann and the Iconoclast, by Charles Carver, Univ. of Texas Press, 1957, p. 178.

[37] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 53, No. 364, March 23, 1895.

[38] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 54, No. 304, Ed. 2, January 22, 1896.

[39] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 54, No. 343, Ed. 1, March 1, 1896.

[40] Lockhart Weekly Post (:Lockhart, Texas ), Vol. VI, No. 30, August 4, 1904.

[41] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 54, No. 365, Ed 1, March 23, 1896.

[42] Brenham Daily Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 21, No. 278, Ed. 1, October 9, 1896.

[43] Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, Texas), Vol. 26, Ed.1, October 22, 1896.

[44] A History of Central and Western Texas, Vol. 2,; Captain B.B. Paddock, p. 710; Lewis Publishing Company, 1911.

[45] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol.56, No. 115, Ed. 1, July 17, 1897.

[46] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 55, No. 68, Ed.1, May 31, 1896.

[47] Gonzales Inquirer (Gonzales, Texas), Vol. 1, No. 23, Ed. 1, November 5, 1853.

[48] Gonzales Inquirer (Gonzales, Texas). Vol. 1, No. 27, Ed. 1, December 3, 1853.

[49] Nacogdoches Chronicle (Nacogdoches, Texas), January 1, 1854

[50] Lockhart Post-Register (Lockhart, Texas), Centennial Edition, article by Florence Swearingen and Katheryne McMillan, August 13, 1936.

[51] Lockhart Post-Register (Lockhart, Texas), Centennial Edition, article by Florence Swearingen and Katheryne McMillan, August 13, 1936.

[52] Texas State Gazette (Austin, Texas) Vol. X, Issue 41, May 21, 1859

[53] The Weekly Telegraph (Houston, Texas), June 1, 1859

[54] Annals of Travis County and of the City of Austin (From the Earliest Times to the Close of 1875) by Frank Brown. Vol. 9. Date unknown. Carleton (or Carleston, as it was spelled elsewhere) would have been thirteen years old at the time of the Texas Revolution.

[55] Lockhart Post-Register (Lockhart, Texas), Centennial Edition, article by Florence Swearingen and Katheryne McMillan, August 13, 1936.

[56] Southern Intelligencer (Austin, Texas), Vol. 4, Issue 25, February 8, 1860.

[57] The Southern Watchman (Lockhart, Texas), Vol. 2, No. 19, June 6, 1857.

[58] South and West (Austin, Texas0, Vol. 1, Ed. 1, December 19, 1865.

[59] The Plow Boy, Vol. 1, No. 2, Ed. 1, December 1, 1868.

[60] Dallas Herald, Vol. 16, No. 35, Ed. 1, May 15, 1869.

[61] American Newspaper Directory, containing Accurate lists of all the newspaper and periodicals published in the United States and Territories, and the Dominion of Canada; Geo. F. Rowell & Co. (1870).

[62] The Texas Almanac for 1871, and Emigrant’s Guide to Texas, page 237.

[63] Texas State Times (Austin, Texas), Vol. 4, No. 20, Ed. 1, May 23, 1857.

[64] Raymond, N.C. Improvement in Compositions Used as Building Materials, Patent, October 12, 1858; texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/6753/metapth 165063/: accessed march 10, 2016.

[65] Houston Telegraph (Houston, Texas), Vol. 36, No. 39, Ed.1, January 5, 1871.

[66] Unknown newspaper, September 9, 1870. www.genealogybank.com/gbnk/newspapers accessed June 9, 2011.

[67] Southern Mercury (Dallas, Texas), Vol. 17, No. 40, Ed. 1, October 6, 1898.

[68] American Newspaper Directory 1894, George P. Rowell & Co., p. 758.

[69] Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Texas), May 20, 1893.

[70] Lockhart Register (Lockhart, Texas), March 24, 1893.

[71] Lockhart Post (Lockhart, Texas), March 10, 1910.

[72] Lockhart Post (Lockhart, Texas), November 24, 1899.

[73] Lockhart Register (Lockhart, Texas), July 10, 1903.

[74] Lockhart Weekly Post (Lockhart, Texas), January 19, 1905.

[75] Lockhart Post (Lockhart, Texas), March 10, 1910.

[76] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/67430176/horace-bruce-roberts

[77] Houston Post (Houston, Texas), Vol. 25, Ed. 1, December 13, 1909 states that the Lockhart Herold (sic) made its appearance that week as the first German paper to be printed in Caldwell County. There is no further evidence of this publication’s existence. It certainly would not have been the first of its kind, if it even existed.

[78] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), May 17, 1872.

[79] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), June 30, 1872.

[80] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), August 15, 1872.

[81] News-Echo (Lockhart, Texas), Vol. 1, No. 7, April 27, 1872.

[82] Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas), Vol. 35, No. 154, Ed. 1, July 7, 1875.

[83] Lockhart Post-Register (Lockhart, Texas), Centennial Edition, November 29, 1972.

[84] Ibid.

[85] Brenham Weekly Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 15, No. 22, Ed. 1, May 28, 1880.

[86] Lockhart Post-Register (Lockhart, Texas), Centennial Edition, November 29, 1972.

[87] Ibid.

[88] The Daily Banner (Brenham, Texas), Vol. 5, No. 176, Ed. 1, July 16, 1880.

[89] Post Register Centennial Edition, op.cit.

[90] San Marcos Free Press (San Marcos, Texas), vol. 14, No. 5, Ed. 1, January 15, 1885.

[91] Post Register Centennial Edition, op. cit.

[92] Yoakum Weekly Herald (Yoakum, Texas), Vol. 16, No. 14, November 10, 1910.

[93] Shiner Gazette (Shiner, Texas), Vol. 17, No. 22, Ed. 1, January 13, 1910.

[94] Post Register Centennial Edition, op. cit.

[95] Houston Post (Houston, Texas), November 12, 1906.

[96] Post Register Centennial Edition, op. cit.

[97] Ibid.

[98] Seguin Gazette-Enterprise (Seguin, Texas), Vol. 108. No. 135, March 23, 1997.

[99] Author’s interview with Arthur Braud, July 11, 2018.

[100] Lockhart Post-Register (Lockhart, Texas), Vol. 126, No. 10, March 5, 1998.

[101] Lockhart Post-Register (Lockhart, Texas), Vol. 112, No. 38, September 20, 1984.

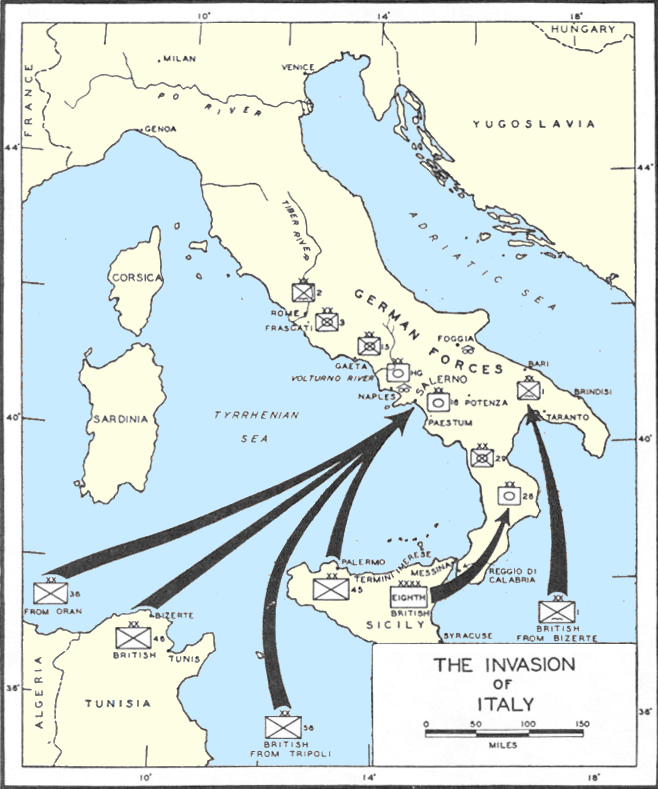

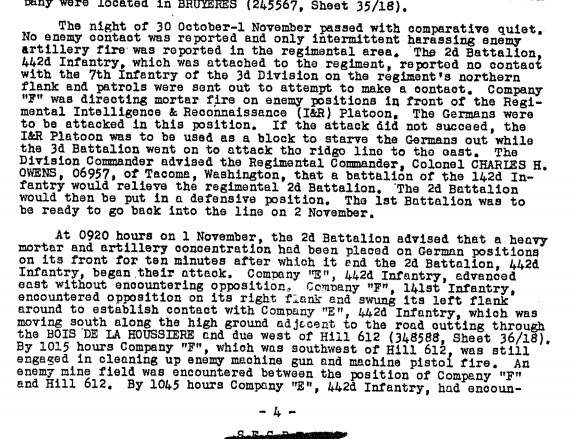

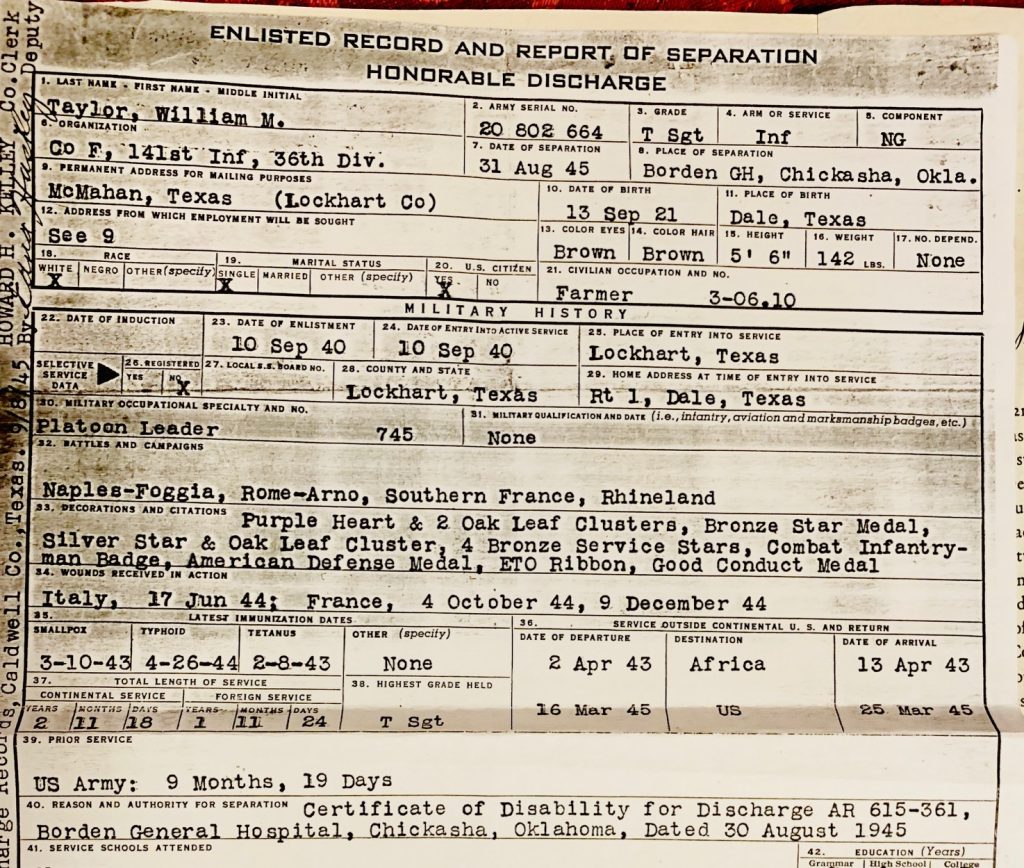

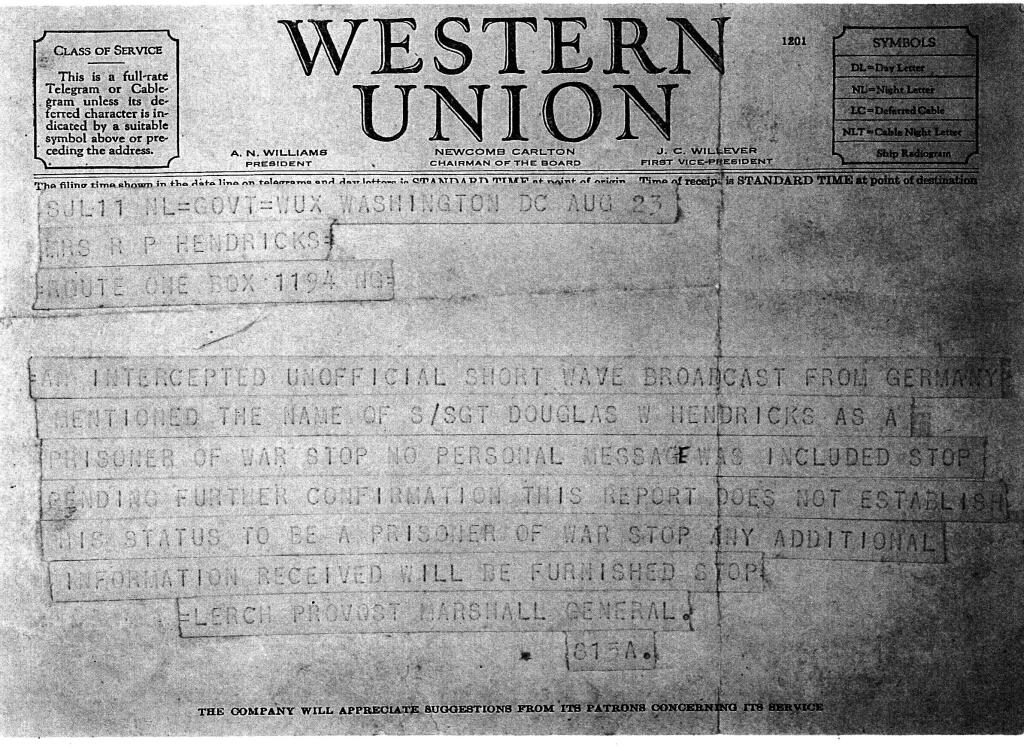

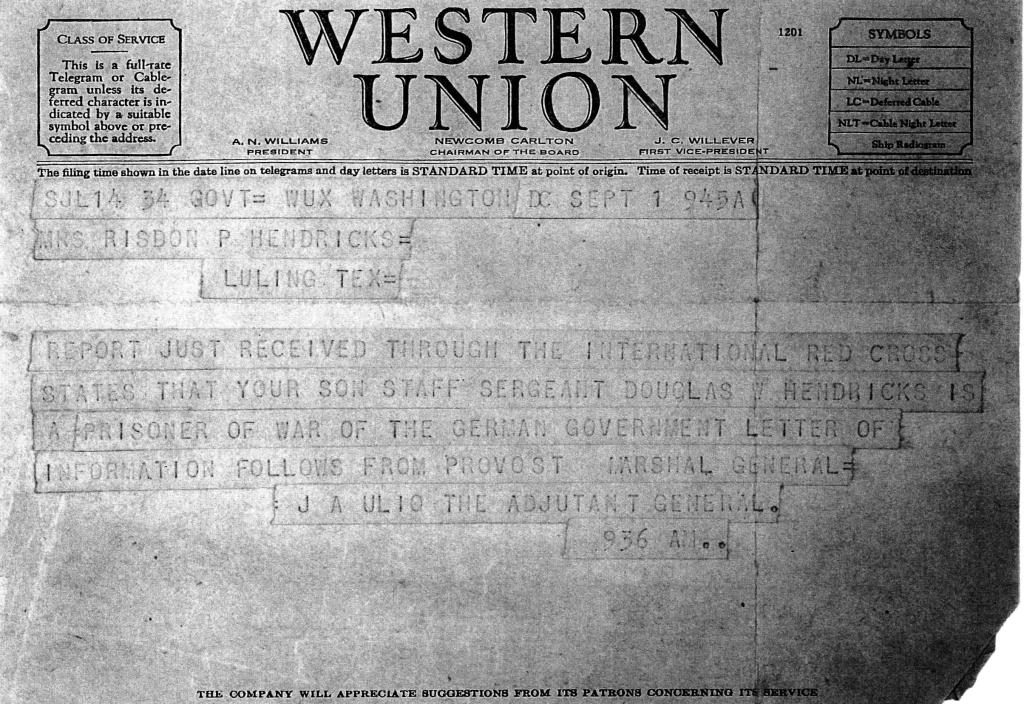

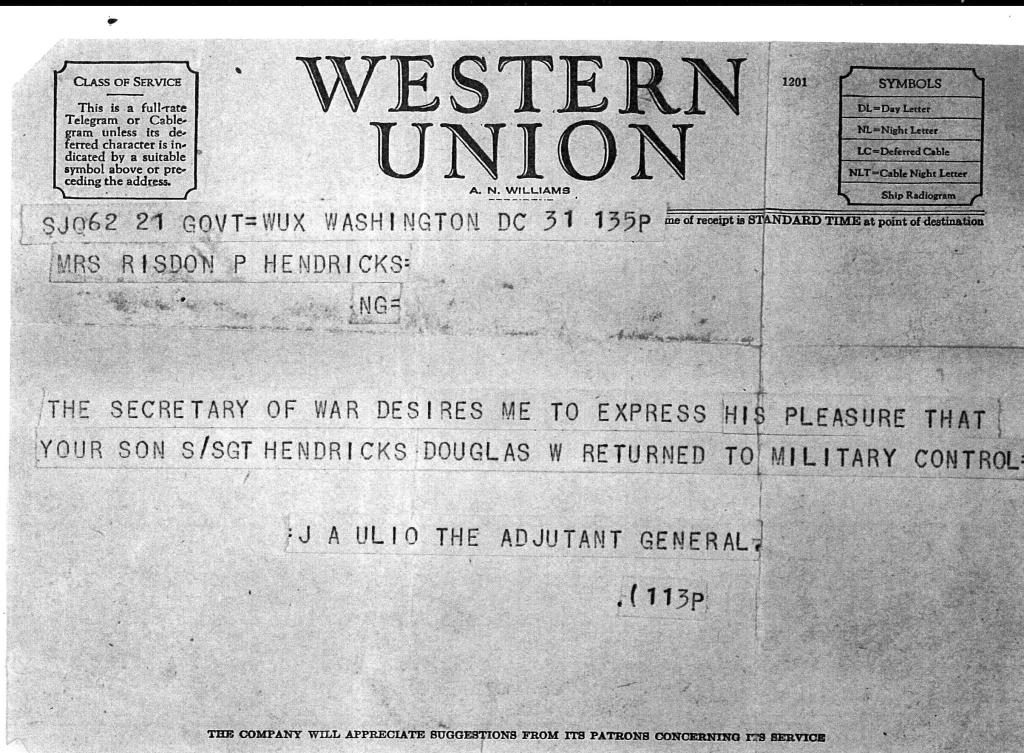

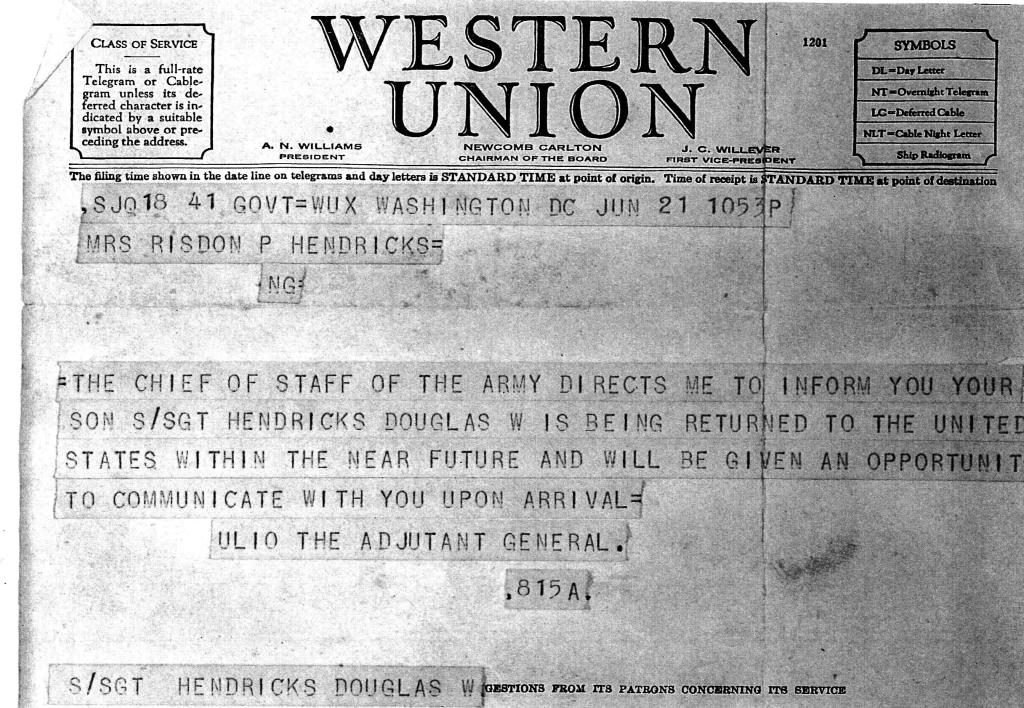

encouraged by older brother Bauzzle, on September 10, 1940, he enlisted at Lockhart in the Texas National Guard’s Company F, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th “Texas” Infantry Division.

encouraged by older brother Bauzzle, on September 10, 1940, he enlisted at Lockhart in the Texas National Guard’s Company F, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th “Texas” Infantry Division.