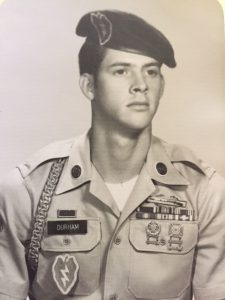

Spec 4 David Durham 1968

DAVE DURHAM

By Todd Blomerth

In the late 1960s, Americans became all too familiar with phrases that burned themselves into the American psyche. One phrase was “the Iron Triangle.”

An area west of Saigon, South Vietnam, and stretching to the Cambodian border, its mention mustered images of jungle fighting, ambushes, tunnels, infiltrating North Vietnamese (NVA), Viet Cong (VC), and death. To young Americans sent to fight in that area of Southeast Asia, the reality was all of these, and more.

I sat down with Dave Durham the other day, and he told me about his abbreviated tour of duty in the Iron Triangle during the Vietnam War. Dave had just celebrated his 70th birthday, and while we didn’t dwell on it, it was obvious that he was glad he has made it this far. In 1967, there was substantial doubt that he would live to see his twentieth birthday.

Dave was born on March 22, 1947 in Velasco, which is now part of Freeport, Texas. Both his mom and dad, Harold “B.H.” and Edna Iris, worked for Dow Chemical, as did most everyone in that area. Dave graduated from Brazosport High School, and then enrolled at Stephen F. Austin University in 1966. He dropped out in early 1967 and “within three weeks” received his draft notice. Like thousands of young men, he was going into the U.S. Army, and once there, into combat in Vietnam.

The United States had allowed itself to be sucked into the vortex of a new and dangerous kind of war in Southeast Asia when it stepped into a role abandoned by the French. Since the end of World War II, guerilla warfare had ebbed and flowed as France, a colonial power, resisted attempts at the creation of new and independent countries in French Indochina. Finally, after a disastrous defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the French gave up, leaving a power vacuum that was, largely, filled by communist and communist-leaning nationalists in the new countries of Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos. As part of the negotiated departure of the French, Vietnam was cut in two, with a demilitarized zone divided communist North Vietnam from the pro-Western South Vietnam. This did little to dissuade communist Viet Cong (VC) and their North Vietnamese allies (NVA) from continuing a war of “liberation” in South Vietnam.

The United States and the West stood by as Stalin gobbled up once-free countries in Eastern Europe. Communist Chinese seized power in 1949, kicking the Nationalists off the Asian mainland. To many, the communists’ efforts in Vietnam were part of a continuing effort at world domination that had to be stopped. Vietnam became to some extent a ‘proxy’ war. The United States and its allies supported South Vietnam. Communist China and the USSR gave its support to South Vietnamese communist insurgents and the North Vietnamese. By the time Dave Durham was drafted, hundreds of thousands of American soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen were engaged in a bloody and widening war.

Dave did Basic Training at Fort Polk, Louisiana. Advanced Infantry Training (AIT) followed. Basic and AIT was ‘brutal,’ Dave recalls. When the new soldiers marched, they were required to yell “Kill” every time their right feet hit the ground. It was just one of the many ways that civilians were indoctrinated to become combat soldiers. Most of the training cadre consisted of combat veterans. They knew what the young men would be up against, and did their best to toughen up the recruits and draftees. However, as Dave says, “nothing can duplicate the misery and horror of war.”

While at Fort Polk, Dave met and became friends with Joe Golf, an Italian-American from Chicago. Fresh out of AIT at Ft. Polk’s “Tigerland”, they were assigned to Charlie Company, 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division. Shortly after arrival in-country, the Regiment was re-assigned to the 25th Infantry Division, known as “Tropic Lightning.”

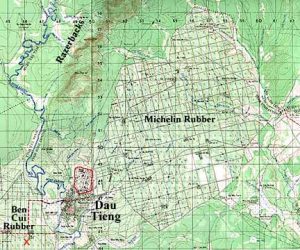

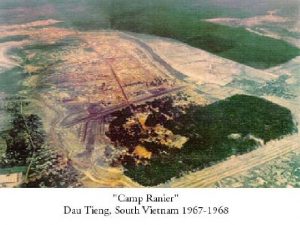

The “Regulars,” as the 22nd Infantry was called, had a proud heritage  stretching back to the War of 1812. In 1967 two of its battalions operated out of Dau Tieng, a large fortified Base Camp, also home to mechanized infantry and Army of Vietnam (ARVN) units. Only 40 miles from Saigon, the Camp lay just to the east of the Saigon River. A mountain range, dubbed ‘the Razorbacks’ lay to its northwest. To its north and east was a vast Michelin rubber plantation. The 22nd Infantry had been in Vietnam since 1966 and had seen much combat. In March 1967, some of its units were involved in a vicious battle at Soui Tre, where over 700 NVA and VC were killed attacking a forward fire base.

stretching back to the War of 1812. In 1967 two of its battalions operated out of Dau Tieng, a large fortified Base Camp, also home to mechanized infantry and Army of Vietnam (ARVN) units. Only 40 miles from Saigon, the Camp lay just to the east of the Saigon River. A mountain range, dubbed ‘the Razorbacks’ lay to its northwest. To its north and east was a vast Michelin rubber plantation. The 22nd Infantry had been in Vietnam since 1966 and had seen much combat. In March 1967, some of its units were involved in a vicious battle at Soui Tre, where over 700 NVA and VC were killed attacking a forward fire base.

Dave processed in at Saigon. Then a C-130 transport flew him the short distance to Dau Tieng’s airfield.

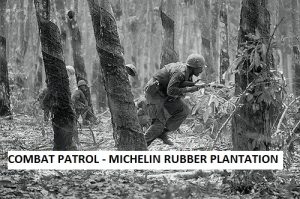

PFC Durham was given a choice: be a machine gunner, an ammo bearer, or be point man on combat patrols. He chose point man. Why did he choose this most dangerous of assignments? “The M-60 machine gun is heavy. Ammunition is heavy. I didn’t want to lug that stuff around.” The Viet Cong moved mostly at night – the Americans mostly during the day. Serving as point man on a patrol meant that Dave quite possibly would be the first man to detect the enemy – and the first man to be detected by the enemy. Not happy with an M-16 in that role, for a time Dave traded for a Stevens short barreled shotgun. Lethal at short range, it proved more burden than benefit. “Shotgun shells are heavy,” recalls Dave. “I could only carry so many. In one fight I ran out of ammunition.” He went back to using the M-16. He could carry many more bullets than shotgun shells.

Active patrolling and search and destroy missions were two methods of taking the war to the enemy. While he was at Dau Tieng, Dave spent most of his time in the field. Troopers would come in, clean up, sleep in sandbagged barracks, let off a little steam – and then repeat the process. There were many contacts with the enemy. Dave recalls being in at least six firefights in his short time at Dau Tieng. Dau Tieng was near the terminus of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The trail actually consisted of hundreds of routes from North Vietnam funneling weapons and fighters for attacks on US and South Vietnamese targets.

Charlie Company kept extremely busy. Road convoys traveling “Ambush Alley” required security. Enemy forces were always present, and battles were common. American patrols crossed rice paddies, which was highly dangerous. In the wide openness, men were easy targets. Search and destroy missions searched out the enemy miles from Dau Tieng. Patrols roamed the huge Michelin  rubber plant, occasionally encountering workers collecting rubber from the trees. “We never knew if the workers were also VC. We were in the middle of a war and this French company was still operating this huge plantation. And being allowed to do it by the VC. It was very weird.” Another combat veteran of that era, Harry Foster, recalls that Americans felt that Michelin was quietly paying off the communists so it could continue its operations.

rubber plant, occasionally encountering workers collecting rubber from the trees. “We never knew if the workers were also VC. We were in the middle of a war and this French company was still operating this huge plantation. And being allowed to do it by the VC. It was very weird.” Another combat veteran of that era, Harry Foster, recalls that Americans felt that Michelin was quietly paying off the communists so it could continue its operations.

Odd memories of combat bubble up sometimes. Dave remembers the Army’s mosquito repellent. It came in small rubber squeeze bottles. “It didn’t work on mosquitoes. But it came in handy for keeping snakes away.” He recalls his unit setting up night ambushes, and hearing snakes slithering toward his position. “I’d squeeze that stuff toward them. They hated it, and would slither off in another direction.” He also recalls the shortage of gun oil for M-16s. “They never gave us enough of it. It was oily, so we’d use the mosquito spray to keep our rifles lubricated. It worked.”

The VC and NVA created a labyrinth of tunnel systems in the Iron Triangle; some extended for miles. Some even went into Saigon. It was not unusual for an American patrol to uncover a hidden tunnel opening. This would be blown closed. First, someone had to ensure no enemy lurked inside, waiting to pop out and attack. Who better to do it that someone slim, agile and willing to be a point man? “They’d hand me a pistol and a flashlight, and I’d go check it out.” Responding to the inevitable question about fear and serving as a “tunnel rat” Dave said simply, “I was scared the whole time I was in Vietnam.”

In late October of 1967, Dave came down with a respiratory infection, and was put on light duty for a week. Coming back from another 25th Division base a few miles away at Cu Chi, he was grabbed up on November 1, 1967, and put into a squad going out for a night ambush patrol. A similar thing happened to his buddy Joe Golf. “I had come in from the field with ear infection,” Joe remembers. “Next thing I knew, I was in on a night ambush patrol.” Dave and Joe knew no one else in the eleven-man squad. “I didn’t know anyone except Joe,” Dave said. “I guessed the others were in a different platoon in C Company.” Research shows that in fact, most if not all of the men in this put-together group weren’t even from C Company.

When on combat missions, normal unit integrity was an absolute necessity. As an example, if you were with 1st Platoon, Charlie Company, you trained with that platoon and company, and you went on operations with that platoon and company. You knew your buddies’ capabilities and shortcomings. You knew your officers and NCOs.

Dau Tieng’s base security patrols were a different story. The September 4, 1967 edition of the 25th Infantry Division’s newspaper, “Tropic Lightning News” tells how these patrols were assembled:

Mixed Nightly Patrols Provide BC Security

DAU TIENG – When the nightly ambush patrol leaves the 3d Bn, 22d Inf, lines at Dau Tieng each evening, it’s a mixed bag indeed – representative of every contingent in the battalion. Along with the ubiquitous medic may go a truck driver, a 4.2 mortar man, an operations clerk, a mechanic or radio repairman, or any of the multiple trades which make the modern infantry battalion function. It’s a training mission for new replacements and the last time out for the old.

While the main infantry elements are on missions far afield, the ambush patrols carried on by these “instant” units are vital in the security of the “Tropic Lightning’s” third brigade base camp.

Joe Goff was ordinarily a Charlie Company assistant machine gunner. On November 1, 1967, Joe told me in his pronounced Chicago accent, “I was carrying an M-16.” Joe continued, “We weren’t expecting anything.” Ambush patrols went out nightly to keep the enemy off guard, and prevent infiltration near the military base. No one wanted to see action. The main concern for the GIs was staying alive.

Leaving during daylight, and moving less than three miles from the Base Camp, the patrol set up for an ambush along a suspected infiltration route somewhere in the Michelin plantation. In groups of threes or fours, soldiers were arrayed in three-prong ambush formation. Trip flares and anti-personnel mines were set up.

Joe and Dave were together with two other troopers they didn’t know, sharing the same poncho liner to stay out of the mud. It was Joe’s turn to sleep when all hell broke loose. “I was asleep and the next thing I knew, someone was covering my mouth with a hand. The VC were about fifteen or twenty feet away. Then a radio mike was keyed, and the world exploded.”

Dave’s memory is similar, but not exactly the same. “We ambushed an enemy unit that turned out to be much larger than our patrol.” He remains unsure of whether the enemy was VC or NVA, or a combination of the two.

Either way, the result was same. “An RPG [rocket-propelled grenade] hit the two men next to me,” Dave recalls. “There were killed instantly. I was hit by shrapnel that wasn’t stopped by their bodies.” His friend Joe, also wounded, pulled him twenty meters back into relative safety, as all hell broke loose. Somewhere in the process, Joe lost his M16 in the mud. Grenades were thrown, gunfire erupted… and then suddenly, it was over. The enemy disappeared into the night, leaving the shaken survivors to their misery. Because the patrol had (possibly) “gone out the wrong gate at Dau Tieng,” in the words of Golf, it wasn’t found until morning. The patrol’s medic ran out of morphine. One soldier’s wounds kept the survivors awake all night with his screams of pain. “With the screaming, there was no question the enemy knew where we were. We were afraid they would come back,” Dave recalls. It was a very long night. Joe remembers firing off a flare as dawn approached. The patrol was eventually found, possibly by a mechanized infantry unit, the 2/22, (the “Triple Deuce”) also from Dau Tieng.

Dave remembers the sound of chain saws. Rubber trees were cut down to allow medevac helicopters in to airlift the wounded. A wounded man medevaced out with Dave constantly screamed in pain. And then stopped. The soldier was either given sufficient pain medication, or died. Dave doesn’t know which.

Initially, Dave was treated at the Division’s medical facility at Cu Chi. Shards of metal had peeled his nose open. The skin was folded back, and sewn up. Because of the chunks of skin torn from his legs and one arm, he was flown to a larger hospital in Saigon for skin grafts. Eventually, PFC Durham was evacuated to an even larger facility outside of Tokyo, Japan.

For several months after the surgeries, he needed a cane to support his walk. Then one day, he received orders —- to return to Vietnam. Fortunately, his treating physician intervened. “You’re still walking on a cane. I’ll take care of this.”

Orders were changed, and instead of Vietnam, the recovering soldier spent the rest of his overseas duty in South Korea. His memories of Korea are pleasant, although the “the whole area I was in smelled of kimchi and honey wagons!”

Because he never returned to his outfit, Dave never knew what happened to the rest of the patrol. He’d heard that eight men were killed. In fact, the best evidence shows two soldiers died violently – the men next to him who’d taken the brunt of the RPG round when it exploded. They were David Tucker, a 20 year-old from Rock Hill, South Carolina. He was in Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 3/22. He is buried at Red Hill Baptist Church Cemetery in Fairfield, SC. The other was 23 year-old Earl Bertmann Miller, a B Company soldier from Missouri. He is buried at St. Bridget’s Cemetery in Pacific, MO.

One veteran with Charlie Company recently recalled the patrol survivors returning to Dau Tieng, and “looking pretty beat up.” But the names of other members of the patrol? Apart from Joe Golf, we still don’t know. Despite the best efforts of reunion locators for Charlie Company and others, they perhaps have been lost in the fog of war and time.

In February 1968, Specialist 4 Durham returned to the United States, out-processing at Ft. Lewis, Washington. It was time to pick up the pieces of his life. He flew back to Texas on a commercial flight, and, as required, in uniform. As he walked past the ticket counter at Houston’s Hobby International Airport, he was confronted by a gauntlet of screaming anti-war protesters. “I’d been gone, and wasn’t aware of everything going on at home.” He was spat on and called “every vile name in the book.” He was thankful his parents were waiting for him elsewhere in the airport, and didn’t have to witness the shameful incident.

Dave returned to Lake Jackson, and re-enrolled in college, eventually graduating from Southwest Texas State University. He also married the love of his life, Nan Rives. He has been in the office supply business for years. Nan recently retired as an art teacher from the San Marcos School District. Dave and Nan have two children. Their son Cole lives in Louisville, Kentucky. He is a professional weight and strength trainer for the AAA Louisville Bats, in the Cincinnati Reds organization. Their daughter Mattisyn (Mattie) lives in Austin.

Dave Durham’s buddy Joe Golf continues to suffer from PTSD. “I can’t sleep at night unless someone is up and awake.” Dave still has shrapnel in his arms and legs. A knee occasionally locks up from the damage it received. His right arm and leg both remain gouged and scarred from the RPG explosion. He’s dealt with the mental issues well over the years, although, as he reminds me, “War is not normal. You can’t go into a war and come back ‘normal.’” Dave Durham has for the most part put the war behind him. What still hurts after fifty years was the way he was treated when he arrived in Houston, Texas. Unlike many veterans, Dave hasn’t been involved in unit reunion groups.

Spec 4 Dave Durham was blessed to return home alive. Over 50,000 of his countrymen weren’t so lucky. Dave doesn’t talk much about his military service. He is a quiet man who feels he was just doing his duty. Be sure to thank him for his service to his country. It is long overdue.

Dave Durham -2017