by Todd A. Blomerth

Earl Millican was a young man who had done well. After graduating from Lockhart High School, he went to work for the Missouri Kansas Texas Railway (the “Katy”) and received several promotions, eventually moving to Kansas. When the United States entered World War I, he enlisted and soon was selected for flight training. He received his initial training at Penn Field (now the site of St. Edwards University) as a bomber pilot. Upon graduation, he was shipped to New York, awaiting transport to France to get into the fight. He never made it. He died in a Long Island Hospital. The Lockhart Post Register’s story of 17 October 1918 reflects the suddenness and tragedy of a young man’s death from influenza:

The deaths of others like Earl Millican were replicated millions of times between 1918 and 1920.

What was “Spanish” Influenza? Well, first of all, its appearance had little to do with Spain. The disease’s appearance in Europe during the Great War was not reported in countries then at war, because of censorship. Spain was neutral, had no wartime censorship issues, and the flu’s rampage through that country’s citizenry was well reported. Hence Spain got stuck with the dubious distinction of getting tagged with the name. For this article, I’ll just refer to the disease as “the flu,” or “influenza.”

With the sudden appearance of the Covid19 virus in the United States in early 2020, and the mystery surrounding its origins, renewed interest has focused on the influenza epidemic that began during World War I. Because the world-wide outbreak occurred before the invention of the electron microscope, and before the development of antibiotics, the cause of the disease was more guessed at than precisely determined.

As noted by researchers Noymer and Gareme :

Influenza is caused by a virus, a member of the family Orthomyxoviridae. The genome of the influenza virus consists of eight single strands of RNA. Formation of new flu strains can occur when a host cell is infected by two existing viral strains. For this reason, there are many strains of influenza virus, which explains why, in the practice of modern medicine, new vaccines, based on surveillance of early cases, are recommended before each flu season. Four aspects that set the 1918 epidemic apart from other flu epidemics are the sheer magnitude of the epidemic, the high mortality rate, the aforementioned unusual W-shaped age profile of deaths, and recent molecular discoveries about the 1918 strain.

All of us have at one time or another been exposed to, or vaccinated against, some type of virus once prevalent in animals. Most come from birds. However, Reid, Fanning, Hultin and Taubenberger noted that “[t]he sequences show little variation. Phylogenetic analyses suggest that the 1918 virus HA gene, although more closely related to avian strains than any other mammalian sequence, is mammalian and may have been adapting in humans before 1918.”

John Barry, in his book, The Great Influenza, states:

In 1918 an influenza virus emerged, probably in the United States-that would spread around the word…Before that worldwide pandemic faded away in 1920, it would kill more people than any other outbreak of disease in human history. Plague in the 1300s killed a far larger proportion of the population – more than one-quarter of Europe – but in raw number influenza killed more than plague then, more than AIDS today.

The lowest estimate of the pandemic’s worldwide death toll is twenty-one million. In a world with a population less than one-third today’s that estimate comes from a contemporary study of the disease and newspapers have often cited it since, but it is almost certainly wrong. Epidemiologist today estimate that influenza likely caused at least fifty million deaths worldwide, and possible as many as one hundred million.[i]

Mainly because of influenza, the average life expectance of an American fell by TWELVE years. This is mind-boggling. As deadly as Covid19 has been, the life expectancy of Americans in 2020 only fell 1.5 years.

Not since the Black Death of the Middle Ages had something this horrific affected so many lives. More chilling was those affected. A large percentage of those killed were healthy young adults. And deaths often came quickly. One example: The Teller (now Brevig) Mission, on Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, was an Inuit village. In November 1918, influenza swept through the tiny settlement and in five days, it killed 72, or 85% of the adult population. The victims were buried in a mass grave in the permafrost. The analysis of lung tissue of several of the victims was crucial in the late 1990s in discovering exactly what the world had been dealing with.

The United States’ population in 1918 was 103 million. A low estimate of flu deaths is 500,000, and most scientists believe the number was closer to 700,000. This translates to .5 percent of the population. Approximately 28% of our country were infected. Over two thousand people are reported to have died of the flu in Texas. Given the largely rural nature of our population and the lack of sophistication in diagnosis, this is probably much too low a figure.

A mild wave of the disease appeared in the Spring of 1918. It was highly contagious, but caused relatively few deaths, then reappeared in August in a more virulent form. Another wave struck, mostly outside of the United States, in the summer of 1919 and once again in 1920. That didn’t mean people stopped dying in the United States. As will be seen later in this article, deaths continued in Texas into 1920.

The first outbreaks of influenza probably began or were immediately exacerbated by the cramped living conditions in make-shift military training camps. America had entered the war in 1917, but it would be over a year before troops in sufficient numbers and training began reaching France. While not as frightening, there were influenza deaths in Army training camps. But then, as troops were sent overseas, and for unknown other reasons, the influenza outbreak abated. The second wave was exacerbated by troops returning from Europe who carried the virus home with them.

It was first described dismissively as “the grippe,” a common enough virus. But when symptoms became worse and the number infected soared, the reality hit that the influenza was like nothing seen before in modern times.

There were warnings. Information dribbled in from Europe, According to Professor Angie Sauer, of Texas Lutheran University:

By early September, sick returning soldiers showed up along the Eastern seaboard. On September 30, Camp Travis, a few miles from downtown San Antonio, reported cases of the deadly influenza. Within days, the camp went into a total shutdown. Fort Sam Houston also reported the disease spreading among soldiers and nurses. Still, the city’s health official was optimistic, even though there were already hundreds of cases reported in the civilian community. This was nothing more than an ordinary wave of “la grippe,” Dr. William Anthony King opined. Good ventilation systems and barring sick people from frequenting entertainment venues would halt the spread of the disease.

But of course, those methods were insufficient.

Even before the more deadly outbreak struck in August, there were deaths. A young lieutenant married for only three months, left for Europe. He and his bride-to-be

had met at the Hebrew Institute, a recreation center on Taylor Street [in Fort Worth] that hosted socials for Jewish solders. Pearl, 24, the daughter of an ice manufacturer, poured punch and danced with the doughboys at those gatherings. Joseph, 29, a Ukrainian immigrant, was a New Yorker with a medical degree from Columbia University assigned to the Army’s 82nd Division.

…

The day the groom departed for France, Pearl wept and grew ill. Her family suspected that sadness, not sickness was overtaking her. Four days later she was dead. The same rabbi who married her buried her. Her tombstone at Emanuel Hebrew Rest on South MainStreet gives no hint of her 86-day marriage nor the poignancy of her death. It simply states: “Pearl Brown, Wife of J.M. Linett. Died July 16, 1918.”

Some people escaped with mild effects, but others experienced much more severe symptoms, including high fever, fluid in the lungs, and head and body aches. Some people seemed to have a standard flu infection but developed pneumonia, which often led to death. Many experienced severe complications that lasted for weeks, like unconsciousness and delirium due to poor oxygenation, and bloody drainage from the nose. Of those that survived, some faced life-long health issues as a result of the flu’s complications.[i]

Prior to the Spanish flu, most influenza deaths had a u-shaped curve, meaning that the death toll was highest among the very young and very old. In contrast, the death toll for the 1918 flu was shaped like a W, affecting the healthy young adults in the middle of the curve more than the young and elderly. Nearly half of the deaths from the Spanish flu were in people between the ages of 20 and 40. The risk of dying from the Spanish flu was greater for people younger than 65 than those older.[i]

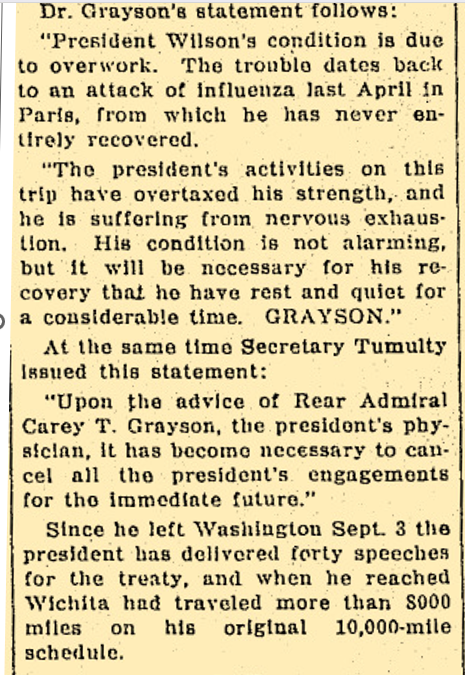

No one was immune from the disease. Texas Governor William P. Hobby contracted it – and survived. President Woodrow Wilson contracted the disease in 1919 while in Paris attempting to negotiate a treaty resolving the many issues that started World War One. It certainly contributed to other serious health issues which shortened his life.

Lockhart Post Register reports on President Wilson’s health 2 October 1919

Matthew Mershon, a writer for Spectrum television, notes that

[A]t first, it wasn’t front-page news at the time due to World War I, but Ben Wright, assistant communications director for the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin, said the threat of what’s commonly referred to as the Spanish Flu was top of people’s minds in 1918.

“There were about 5,000 Texans that died in World War I, that includes nurses,” said Wright. “But about a third of those casualties were from influenza rather than battlefield deaths.”

Cases started popping up in Texas toward the end of September 1918. By October 1, 1918, 31 counties in Texas were reporting cases of influenza, many within military installments.

“Congregations of soldiers are natural incubators for the Spanish Flu during the fall of 1918,” said Wright, adding that an unorganized dispersing of soldiers post WWI helped the virus spread through the public.

By mid-November, an Associated Press article noted more than 150,000 cases of influenza had been reported to the Texas State Health Department.

“We’re talking about a Texas that has a population of under five million at the time, so it’s a smaller place than today,” said Wright.

Throughout October 1918, cities across Texas would implement non-essential business closures, similar to the ones in place now to help battle the spread of COVID-19.

“Businesses, churches, schools, the University of Texas – all were closed,” said Wright.

According to an Associated Press clip dated October 16, 1918, the City of Waco ordered the closing of all “schools, picture shows, theaters, and other places for public gatherings on account of the epidemic of Spanish influenza.”

But when many of the quarantine orders were lifted in the fall of 1918, a second wave of influenza would hit. Barracks built on the UT Austin campus would eventually be turned into hospital wards.

Similar to the political pressures of today’s pandemic, back in 1918 many Texas officials grappled with issuing another quarantine or not. In Austin, the mayor back then decided against it.

“The mayor – a gentleman called A.P. Wooldridge – declined to declare another quarantine in part because he didn’t think there was public support for it – and he didn’t think it would be effective unless it was extremely strict,” recalled Wright.

In a 1918 health bulletin, The Texas State Board of Health urged school leaders how to stop the spread of the flu:

“Every day . . . disinfectant should be scattered over the floor and swept. All woodwork, desks, chairs, tables and doors should be wiped off with a cloth wet with linseed, kerosene and turpentine. Every pupil must have at all times a clean handkerchief and it must not be laid on top of the desk. Spitting on the floor, sneezing, or coughing, except behind a handkerchief, should be sufficient grounds for suspension of a pupil. A pupil should not be allowed to sit in a draft. A pupil with wet feet or wet clothing should not be permitted to stay at school.”

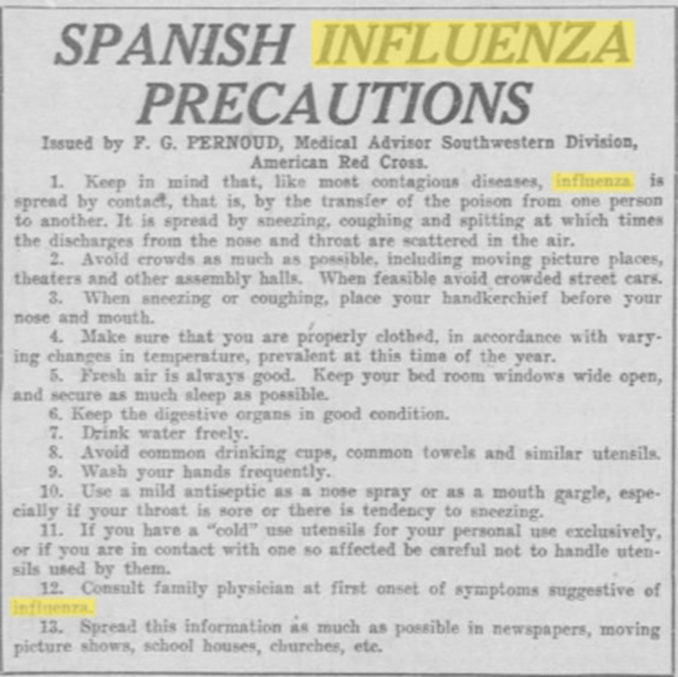

The electron microscope had not been invented. It was impossible to isolate or identify the deadly organism. The transmittal of influenza was not totally understood, although some preventive measures probably reduced its effect – when used. Some advice was just plain common sense. An advice column by a Dr. W. Evans, printed in the Galveston Daily News of 12 December 1918 urged people to “[avoid becoming tired, avoid becoming chilled, avoid getting wet…”

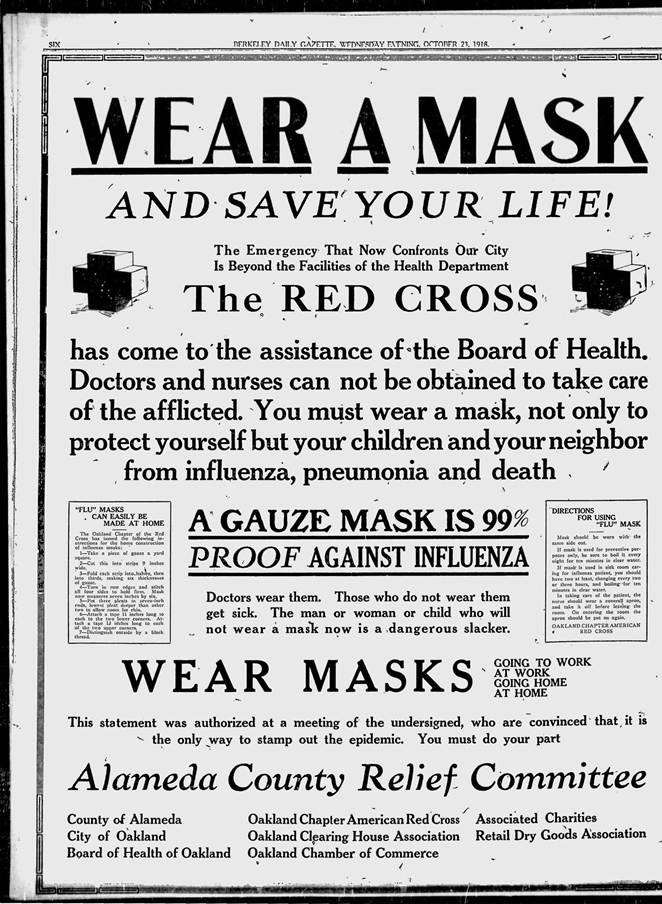

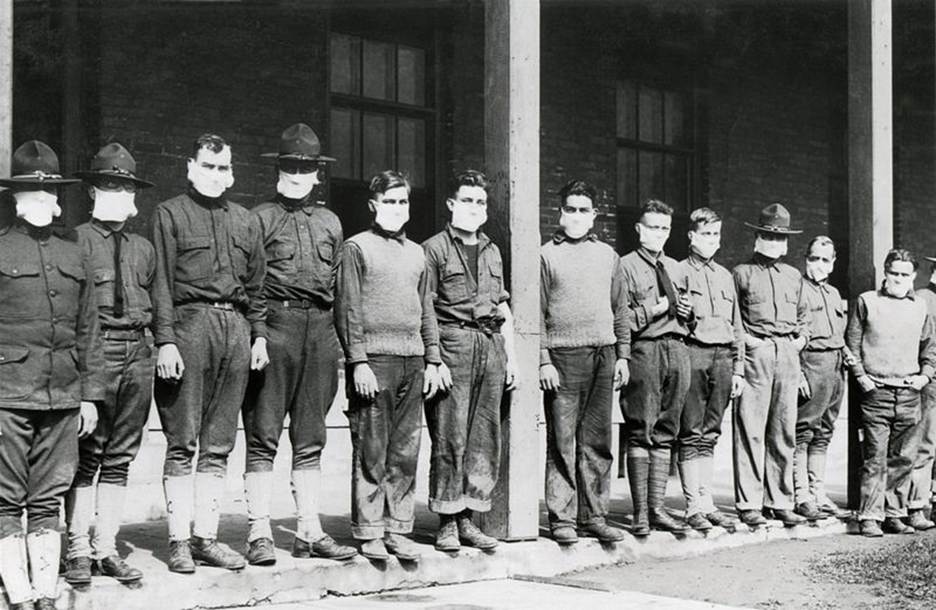

Masks were required on military training posts, and cleanliness was re-emphasized. Most controversial, as now, was the closing of businesses and schools.

Soldiers with gauze masks at a training camp

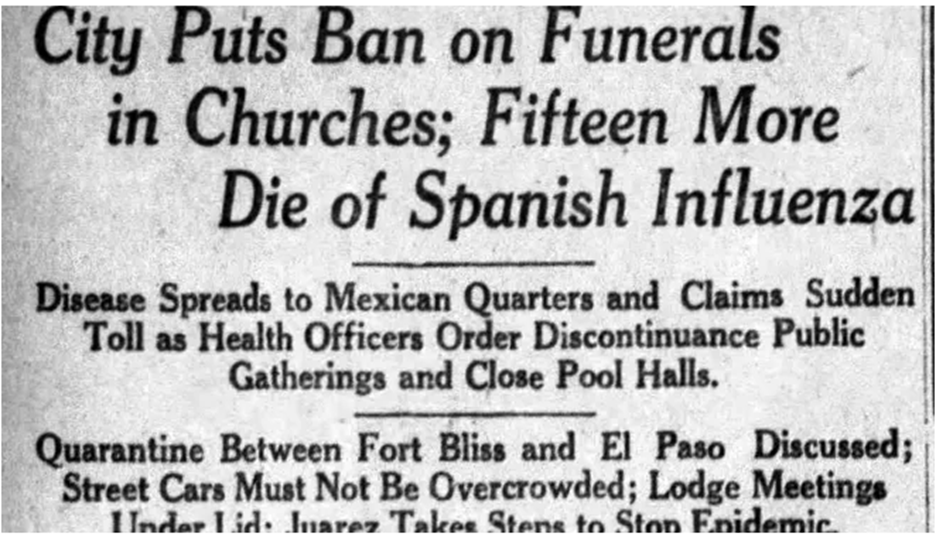

8 October 1918 El Paso Herald

A typical plea for wearing masks, this one from Alameda County, California

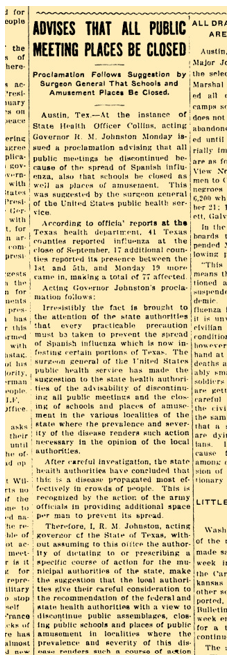

It appears that most school and church closures occurred in October of 1918. September found 44 counties with active cases. The number jumped to 71, and Texas’ acting governor, R.M. Johnston authorized the State Health Office to issue a proclamation ‘advising’ that all public meetings be discontinued.

Lockhart Post Register 17 October 1918

Many local governments, schools and businesses took the advisory seriously. ‘Colonel’ Baker announced the same edition of the Post Register that the Baker Theater would close temporarily. Mayor T.B. Coopwood shut down schools and stopped all unnecessary gatherings:

Lockhart Post Register 24 October 1918

The Dixie Lyceum discontinued its presentations that same date. “One death among our citizenship by the epidemic now so prevalent over the state would be a great grief to every one [sic], and the Lyceum management does not care to take the risk of exposing anyone to the disease. Be patient and when conditions justify affairs will adjust themselves.”

The sheer numbers of those infected was shocking. Perhaps more so were the stories of death and suffering. The oil boom hadn’t hit Caldwell County yet, but in those counties where there was large exploration and production, influenza was devastating. Gene Fowler, writing in the October 2020 magazine, Texas Co-op Power, looked back on oral histories from the Briscoe Center of Oral History tells some recollections:

Texas oil boomtowns suffered. The Briscoe Center of Oral History contains many stories of the shock that enveloped early oil producing centers such as Burkburnett, Ranger and Desdemona. Walter Cline, who later became Burkburnett’s mayor was the Red Cross director in an oil field near Wichita Falls. When the epidemic hit, he rushed to Burkburnett with doctors and nurses, he recalls his team found people “suffering from flue and exposed in covered wagons and under these tarpaulins. In one place, you’d find a mother dead, with a little 6-or 8-months-old baby crawling around over her breast, trying to open her dress…I think on our first trip west of Burkburnett, we gathered up some six or eight dead men, women and children, and they continued to die until we found temporary shelter for them.”

Fred Jennings, a rig operator near Baytown, recalled, ‘The people died, and they just died so fast here till they didn’t have any undertakers. You’d just have to put them in pickup trucks and haul them to Houston. Just put them in a pine box and bury them any way you could… I saw one man working and walk home and was dead in 30 minutes.”

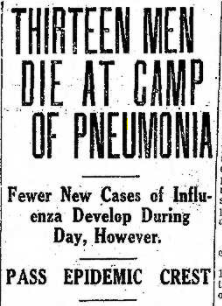

As mentioned, the burgeoning US Army training camps were ideal contagion centers. On 13 October 1918, the San Antonio Light reported that thirteen young soldiers died at Camp Travis in less than one day, and yet assured the public that the disease count would soon begin to drop:

Many of influenza’s victims, with weakened immune systems, became susceptible to bacterial pneumonia. There were no antibiotics available. A suffered may have avoided immediate death, only to succumb to the secondary infections.

Houston was home to Camp Logan, located in what now is Memorial Park. A Houston newspaper reported in September of 1918 that over 600 soldiers were infected with influenza. By the end of 1918, over 100 soldiers would die of the disease.

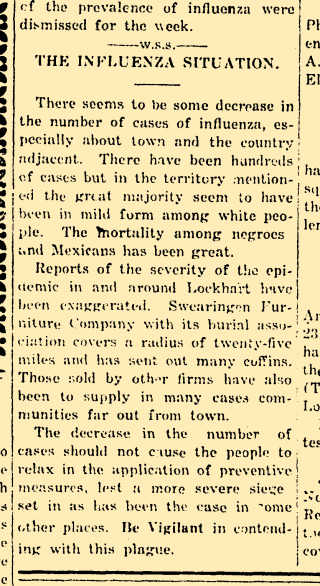

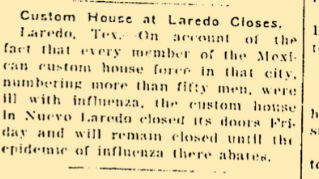

Border areas were hit hard, as were poor areas of towns and cities. The border crossing at Laredo was closed. The poor and densely populated Chihuahuita barrio in El Paso suffered far more deaths than the more affluent Anglo areas. Caldwell County’s newspapers acknowledged that “the mortality among negroes and Mexicans has been the greatest.”

Lockhart Post Register 24 October 1918

Lockhart Post Register 17 October 1918

El Paso Times 9 October 1918

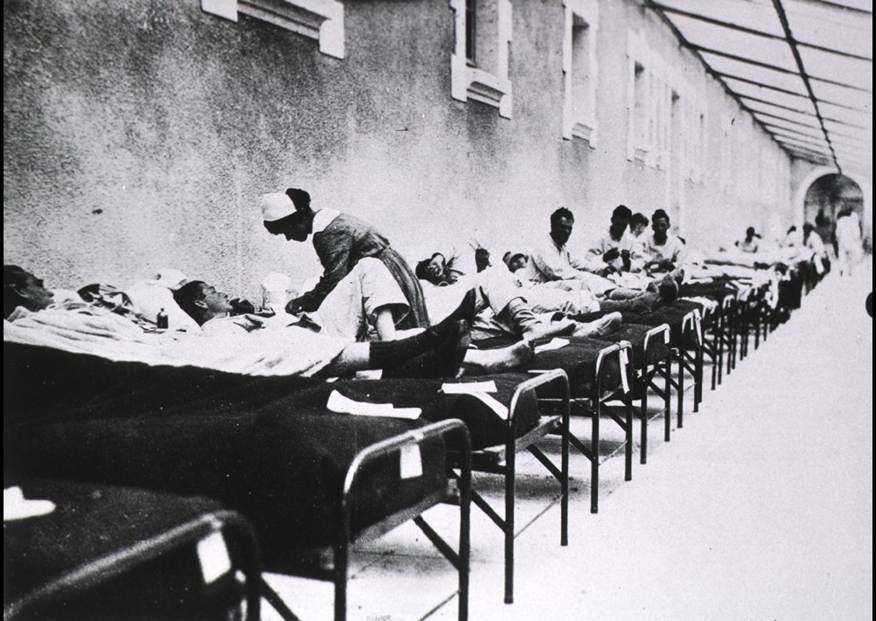

An Army Hospital Ward, Washington, DC – 1918

Walter Reed Hospital – masked nurse cares for a soldier outside a crowded ward in November 1918

Nurses caring for stricken soldiers – Vaclaire, France

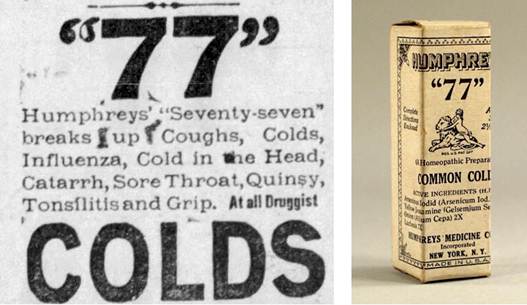

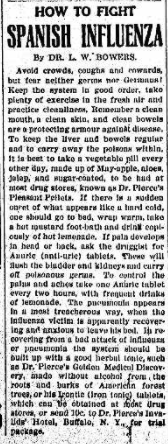

Covid19 had its share of misguided or quack remedies suggested. 1918 was no different. And, there were less controls on advertisement and supposed ‘cures.’ A few of these quack remedies are shown below. Some of these ‘medicines’ contained up to 18% alcohol and opiates.

Ads collected from Lockhart, Flatonia and Austin newspapers. Even a laxative was suggested.

Dr. Pierce’s Pleasant Pellets

There were scientific attempts to combat the disease, apart from social distancing and masking. A Houston Chronicle story from 2020 noted:

Of particular note, researchers found six controlled studies in which the use of blood plasma, serum or whole blood from recovering flu patients reduced the mortality rate of severely ill patients during the Spanish Flu era. According to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, featured authors in the medical literature of the time suggest that antibodies in the blood products help stem the effects of the flu virus.

“Patients with Spanish influenza pneumonia who received transfusion with influenza-convalescent human blood products may have experienced a clinically important reduction in the risk of death,” noted Thomas C. Luke of the New Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. The report was published by Annals of Internal Medicine.

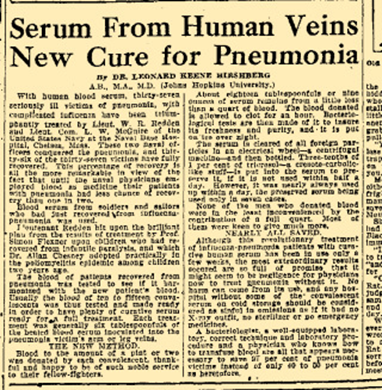

One, from Johns Hopkins University, was widely mentioned in the press:

San Antonio Light 6 January 1919

But by the time most studies were completed, the disease had burned itself out in the United States.

Despite dire warnings, outright bans on meetings and assemblies didn’t last long. Most were lifted in November 1918. Newspaper clippings offer an idea of how quickly the disease hit, then, for most, seemingly disappeared. When a flareup occurred in December, an attempt in San Antonio to shut public buildings once again. This was met with great resistance.

The Flatonia Argus November 7, 1918 edition claimed that things were getting better. While its headlines (along with almost every other American newspaper) dealt with the approaching end to the Great War, the influenza epidemic was mentioned:

“Conquering of the influenza epidemic has started the machinery in the depot brigade grinding again and recruits, held back for several weeks, now are pouring into Camp Travis by the hundreds from Texas and Oklahoma.”

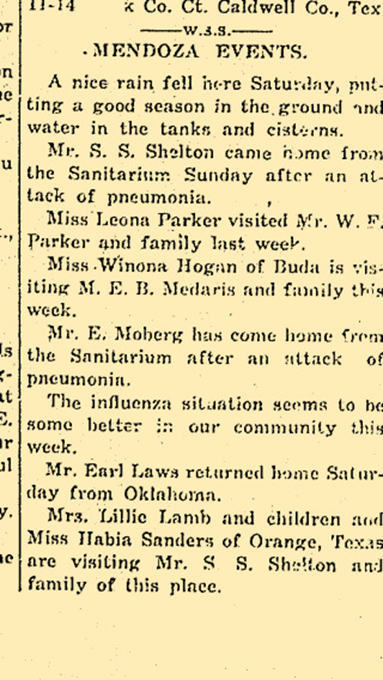

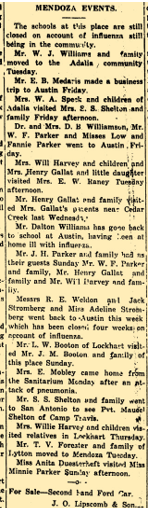

A local example are notices from the Post Register on the happenings in the community of Mendoza.

On October 21, things were supposedly getting better, but Mendoza schools remained closed on November 7, 1918 …

…while on the same day Lockhart reopened for business!

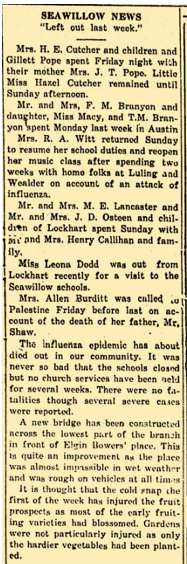

And the Seawillow schools were never closed during the entire pandemic. (Lockhart Post Register 11 March 1920)

As confusion and controversy reigned, the illnesses continued. Jennie Mae Baker, from Lockhart, became ill at the College of Industrial Arts (now Texas Women’s University). The Post Register noted that her mother, Mrs. R.D. Baker, traveled to Denton to care for her ailing daughter. Dan Connolly moved to care for his seriously ill brother, J.T. Connolly.

Lockhart Post Register 30 January 1919

And a Lockhart High School teacher was unable to return after the Christmas because of the disease:

Lockhart Post Register 2 January 1919

While the disease did the most damage in the last four months of 1918, the deaths in the United States continued as a substantially lower rate well into 1920. The disease affected everyone. The stories of sudden deaths were legion. Below are a sampling of everyday news stories during that period.

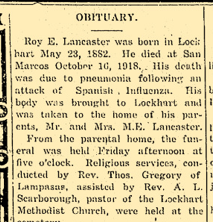

Roy Lancaster, a prominent citizen of San Marcos, died suddenly and was brought back to Lockhart for burial. Lockhart Post Register (24 October 1918)

Constance Petrosky’s death was announced by the Post Register on 12 December 1918. Taken sick in Oklahoma, he started for Lockhart and died shortly after arriving home.

The suddenness of death after onset was a familiar theme. The Lockhart Post Register 2 January 1919 edition describes the death of Wood Harris. A resident of Marshall, Texas, Mr. Harris and his wife began a trip to Atlanta, Georgia, presumably by rail. He became ill enroute and died shortly after arriving.

Vernon Ellison apparently suffered long-term effects from the disease, which was not uncommon. Seen around town one morning, he succumbed to the disease’s side effects that afternoon.

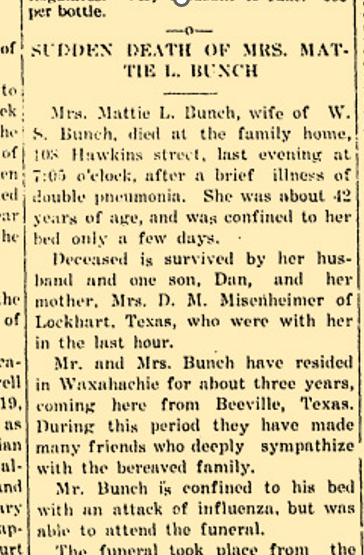

Mattie Bunch, originally from Lockhart, and a resident of Waxahachie, took ill and died suddenly. Although seriously ill with influenza, her husband was able to attend her funeral. Lockhart Post Register 12 February 1920.

Mrs. R.T. Yates, originally from Lytton Springs, was a schoolteacher in Robstown. She was taken ill and died soon thereafter. Lockhart Post Register 6 March 1919.

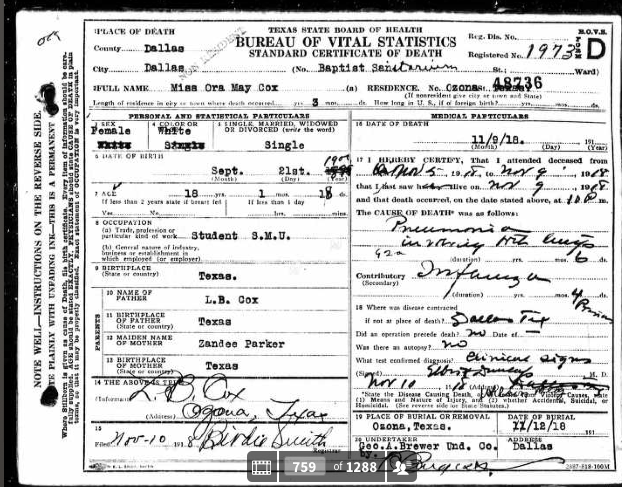

An tragic example of a life snuffed out is that of Ora Mary Cox. While attending Southern Methodist University, this Ozona native became ill on November 5, 1918, and died four days later.

The influenza pandemic eventually burned itself out, but not before catastrophically affecting all parts of the globe. The United States was fortunate to have only lost as many as it did. Hopefully, it serves as a warning that it could happen again.