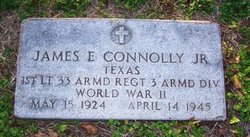

JAMES EDWARD “MACK” CONNOLLY JR.

JAMES EDWARD “MACK” CONNOLLY JR.

Page One of the Post Register of May 8, 1945 announced boldly, WAR IN EUROPE ENDS; VE DAY SOLEMN DAY IN LOCKHART. In part this was because information had just been received that Lt. Mack Connolly, son of Mr. and Mrs. J.E. Connolly Sr., had been killed in Germany.

“The effect of the news on Lockhart people was depressing in the extreme. It was passed from one to another in whispers or low tones. Another son, one of the flowers of Lockhart manhood, gives his life in the cause of Freedom just as the day of Liberty is dawning over the world.”

Mack was the son of James Edward Sr. and Jessie Mary (McMillan) Connolly. He was the older brother by eight years to Dr. J. Tom Connolly. The family lived at 617 S. Brazos in Lockhart. He was born on May 15, 1924. Mack’s circle of friends included Herbert (Herb) Reid Jr., Fleetwood Richards, and Forrest (Jack) Wilson. All played football on the high school team. In the words of Jack Wilson, “Mack was the best guy in the world.” He recalled Mack’s mother would feed some of the team steaks every Friday night, Mack and his friends adored her. Mack graduated from Lockhart High School in 1942, and enrolled at Texas A&M. Leaving school to enlist, he later became an officer.

In late July 1944 while home on leave, he attended a Business Men’s Club luncheon where the topic of post-war use of government built tanks for stock water was discussed. The newspaper’s playful report of the lunch noted that “Lt. Mac[k] Connolly was called on to state what he wanted. He replied that at present he was just trying to learn enough to be able to get back when the war was over.”

Mack married Mariellyn (“Dink”) Andrews on September 23, 1944 at Fort Sill Oklahoma. The Connolly family and Mack’s bride-to-be traveled together from Texas so that all could attend the wedding.

At some point Mack was assigned to Company I, 33rd Cavalry Regiment of the 3rd Armored Division. The 33rd Cavalry’s unit nickname was “Men of War.” It was richly deserved. Described as part of the “massive tank battering ram which made the 3rd Armored Division famous,” its M4 Sherman tanks had a splendid combat record. However, the M4 Sherman also had a reputation as a crew killer, because of its tendency to explode if taking a direct hit. Its nickname was the “Ronson” (a cigarette lighter that was guaranteed to “light up the first time”).

At some point Mack was assigned to Company I, 33rd Cavalry Regiment of the 3rd Armored Division. The 33rd Cavalry’s unit nickname was “Men of War.” It was richly deserved. Described as part of the “massive tank battering ram which made the 3rd Armored Division famous,” its M4 Sherman tanks had a splendid combat record. However, the M4 Sherman also had a reputation as a crew killer, because of its tendency to explode if taking a direct hit. Its nickname was the “Ronson” (a cigarette lighter that was guaranteed to “light up the first time”).

Mack was one of the many replacement officers and men inserted as the attrition of constant  combat across Europe served as a meat grinder on Allied forces pushing the Germans back into the Fatherland. The unit had fought across France’s hedgerows reaching Belgium in September 1944. The Division was part of the northern ‘neck’ that held, then closed on the Germans during the winter Battle of the Bulge. It swept into Cologne in March of 1945 and then crossed the Saale River speeding toward the agreed meet-up point with the Russians on the Elbe River. On April 11, 1945 it freed the survivors of the horrific concentration camp of Dora-Mittlebau.

combat across Europe served as a meat grinder on Allied forces pushing the Germans back into the Fatherland. The unit had fought across France’s hedgerows reaching Belgium in September 1944. The Division was part of the northern ‘neck’ that held, then closed on the Germans during the winter Battle of the Bulge. It swept into Cologne in March of 1945 and then crossed the Saale River speeding toward the agreed meet-up point with the Russians on the Elbe River. On April 11, 1945 it freed the survivors of the horrific concentration camp of Dora-Mittlebau.

As the war wound down, and with Germany’s surrender clearly in sight, many families were tortured by the possibility that a loved one would be killed with the war practically over. Certainly the Connolly family and Mack’s bride must have feared that.

On the Western Front, German soldiers were surrendering by the thousands. Many were fleeing the Russian advance on the Eastern Front, seeking to escape the tender mercies the expected retribution exacted by the Soviet Union would offer, either by summary execution or slow death in the Gulag. The Wehrmacht, the German regular army, was crumbling, as its manpower and command structure ebbed away – regular army soldiers knew to expect humane treatment as prisoners of the French, British or Americans. The only units still offering any real resistance to the western Allies were SS units, and Hitler Youth – both imbued with a fanaticism that transcended the reality of Germany’s impending defeat. Many of these units had panzerfausts – shoulder mounted single shot anti-armor weapons that were very effective.

The 33rd’s final action was an intense battle to take the German city of Dessau. Mack was killed in that battle on April 14, 1945. Notice of his death came four days before VE Day. In October 1945, he was posthumously awarded the Silver Star, the Armed Forces’ third highest award for valor. His wife accepted the award on Mack’s behalf in a solemn ceremony at Camp Swift. The citation reads as follows:

Lt. Connolly was leading his platoon of tanks in the vicinity of Dessau, Germany, when the tank in front of his was hit and disabled by bazooka fire. Although he was without infantry support and he was in the face of well emplaced bazooka teams, he went forward with total disregard for his safety in order to enable the crew of the disabled vehicle to withdraw. His tank was also hit and he was killed. Lt. Connolly’s courage and devotion to duty reflect the highest of credit upon himself and the armed forces of the United States.

Mack died one month before his 21st birthday.

Mack’s body was eventually returned home. Final rites were held at his parents’ home at 617 S. Blanco on February 2, 1949. Pallbearers were his boyhood frineds, Jack Wilson, Fleetwood Richards, Herb Reid, Newton (Doc) Wilson, Jesse Burditt, Tom Burditt, and George (Bubba) Chapman. After the reciting of the 23rd Psalm, he was buried in the Lockhart Cemetery.

Dink later married Herb Reid, Mack’s boyhood friend. She passed away in 2002.