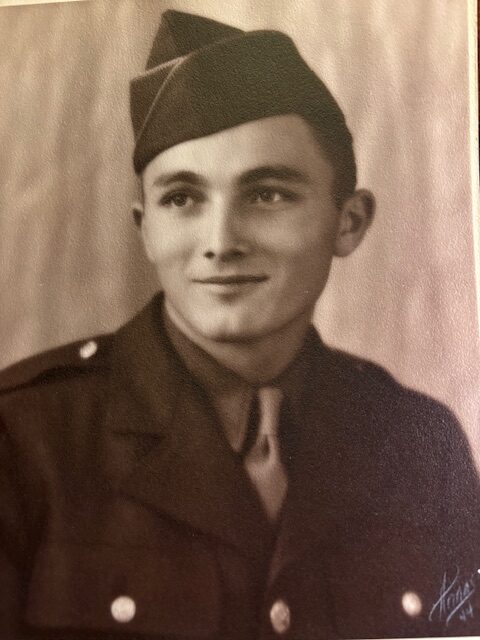

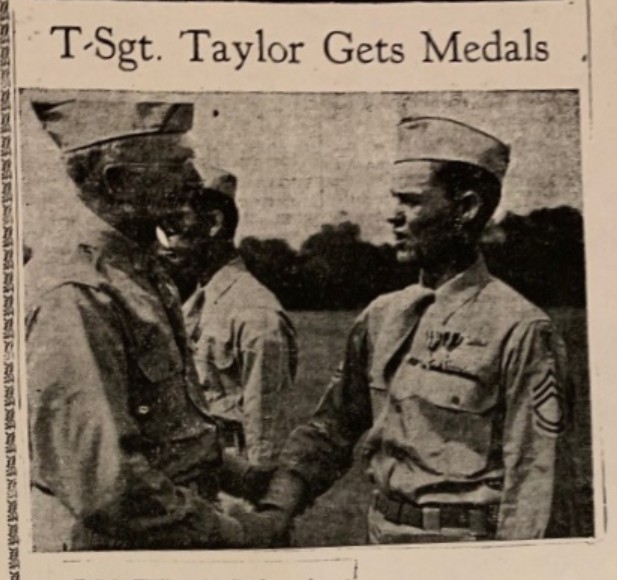

J. LOUIS MOHLE – A LOCKHART BOY THAT WENT TO WAR – AND LATER BECAME A NEWSPAPER OWNER AND EDITOR

By TODD BLOMERTH

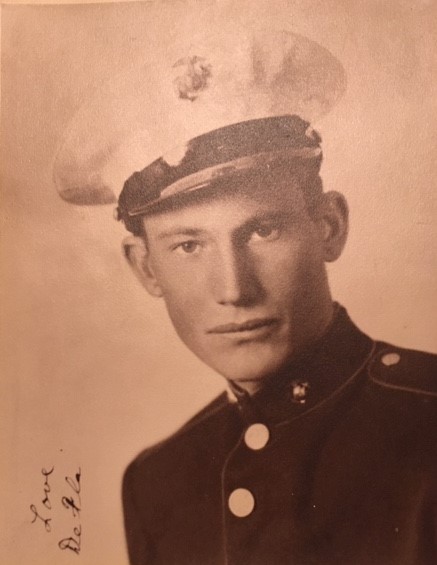

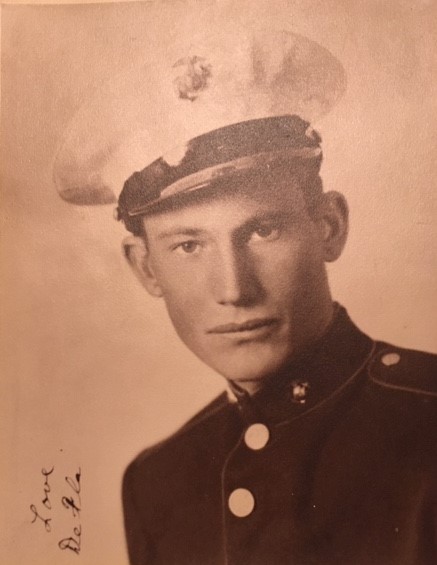

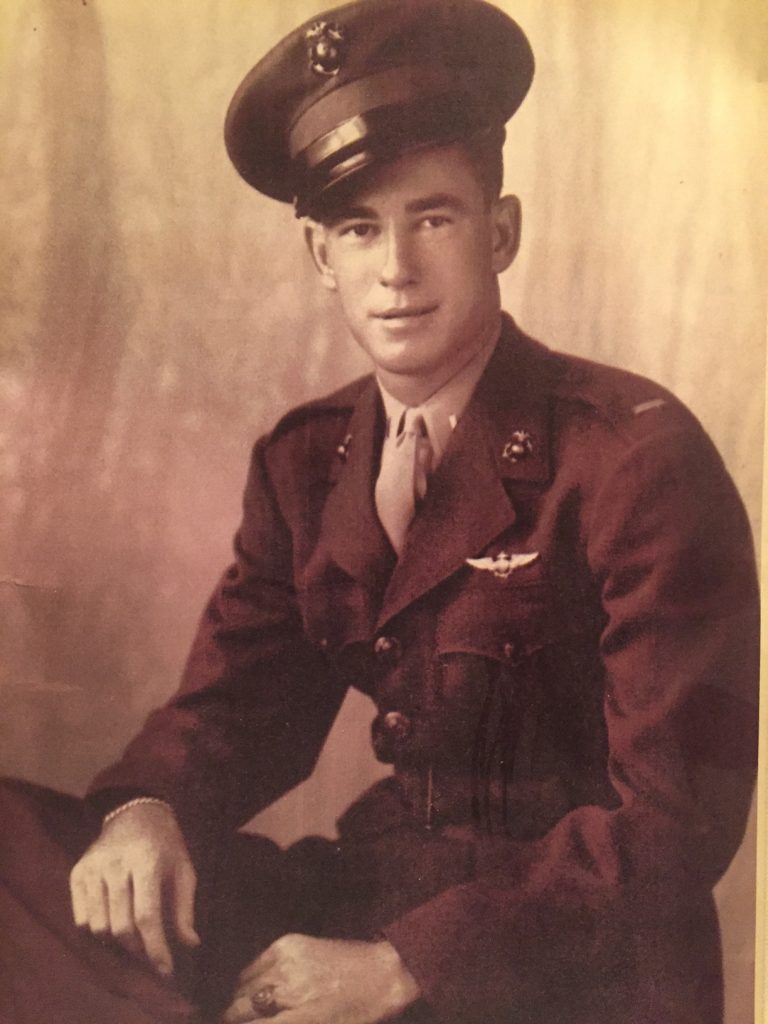

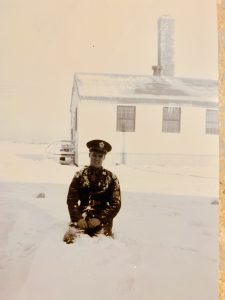

J. LOUIS MOHLE AS A USAAF RECRUIT

I want to tell you a story about Jesse Louis Mohle, Jr. Newcomers to Caldwell County didn’t have the privilege of knowing him. But many ‘old timers’ (and not-so-old timers) were blessed to know Louis and appreciate his many contributions to Caldwell County.

His great grandfather, Carl “Charlie” Anton Mohle was born in Giforn, Hanover, in what later became part of the German Empire, in 1808. He emigrated to the United States, and lived in Galveston, where Louis’s grandfather, Henry Francis Morton Mohle was born in 1851. The family moved to Lockhart, and Louis’s father, Jesse Louis Mohle was born in 1894.

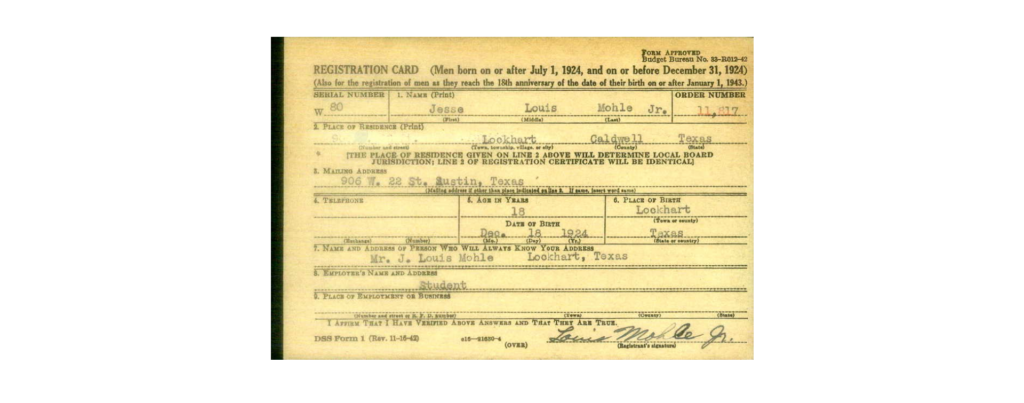

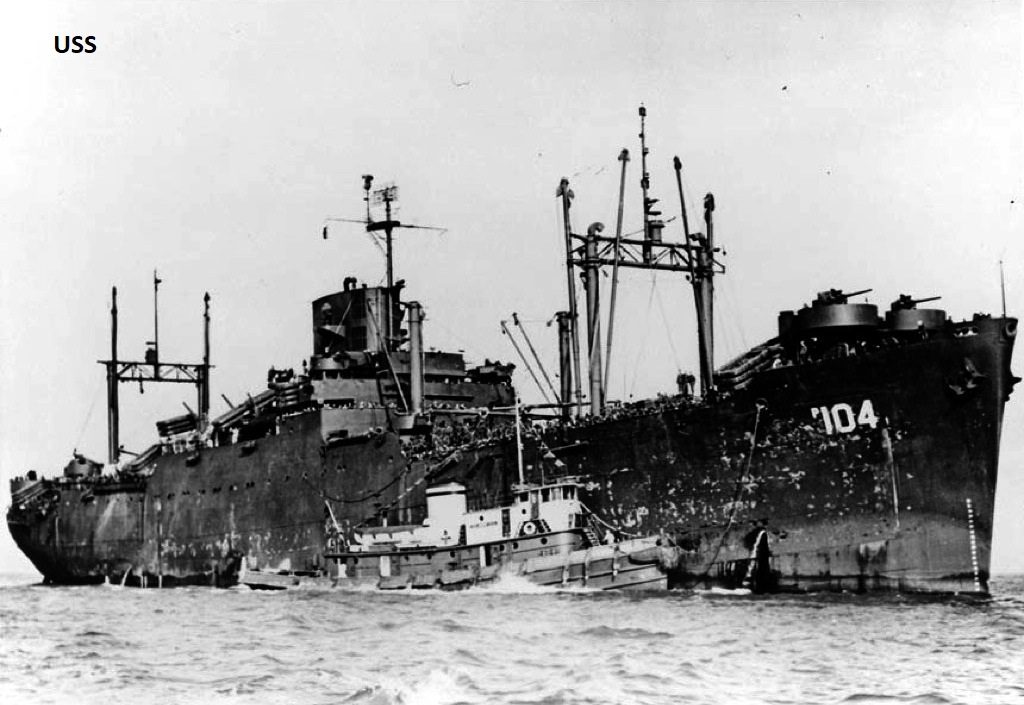

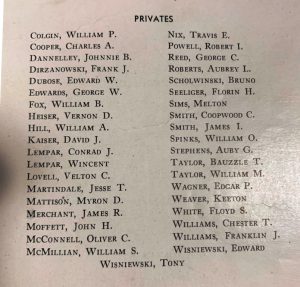

Louis Senior, who enlisted in the US Army and served overseas in World War I, listed his employment in 1917 as a printer. He became a soldier in Company D, 141st Infantry, 36th Infantry “Texas” Division, shipping out from Hoboken, N.J. on the USS Finland on July 26, 1918. After returning from Europe, he met Louis’s mother, Mildred Marjorie Finfrock in Houston, and they were married in 1923. Jesse “Louis” Mohle, Jr. was born in Lockhart, Texas 18 December 1924. Younger brother, Paul Henry Mohle, came along six years later. The couple also lost an infant child in 1933.

LOUIS AND PAUL MOHLE, WITH THEIR MOM – 1930S

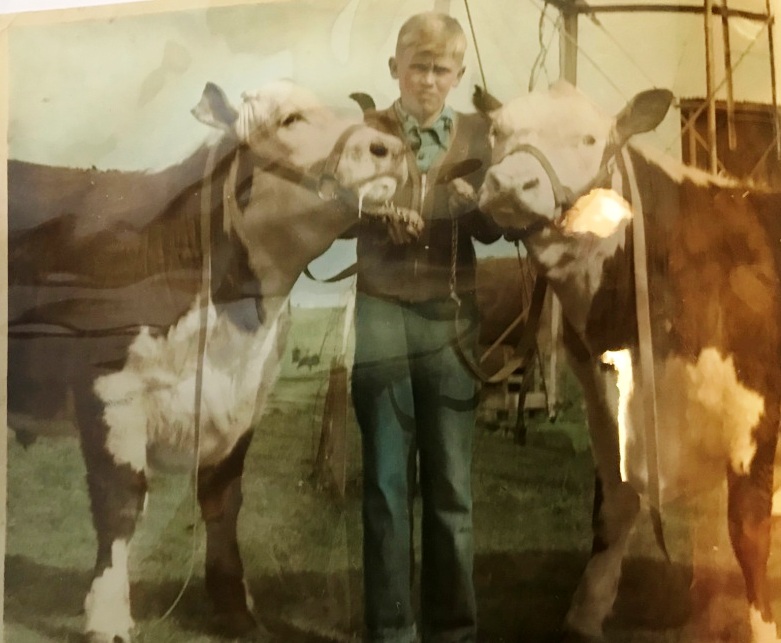

The Mohle family lived at 121 Trinity Street. Louis Senior owned a farm, and became a part-owner in the Lockhart Post Register, eventually acquiring the newspaper in its entirety in 1940.

Louis was a typical Lockhart child of the 1930s. Already blessed with a good singing voice as a young boy, he often sang in the First Christian Church. Harry Hilgers remembers the time Harry, his brother William, Louis Mohle and cousin Bobby Mohle, at a church summer camp at Center Point on the Guadalupe River, were recruited by the camp minister to sing as a quartet as part of a church service on the banks of the river. The plan was for the boys to sing “Jesus Savior, Pilot Me,” from a boat drifting downstream. Suddenly, the boat began to sink near the gathering. Fortunately, a sandbar allowed the singers to keep their heads above the water, and continue to harmonize “Unknown waves before me roll, hiding rock and treacherous shoal…”

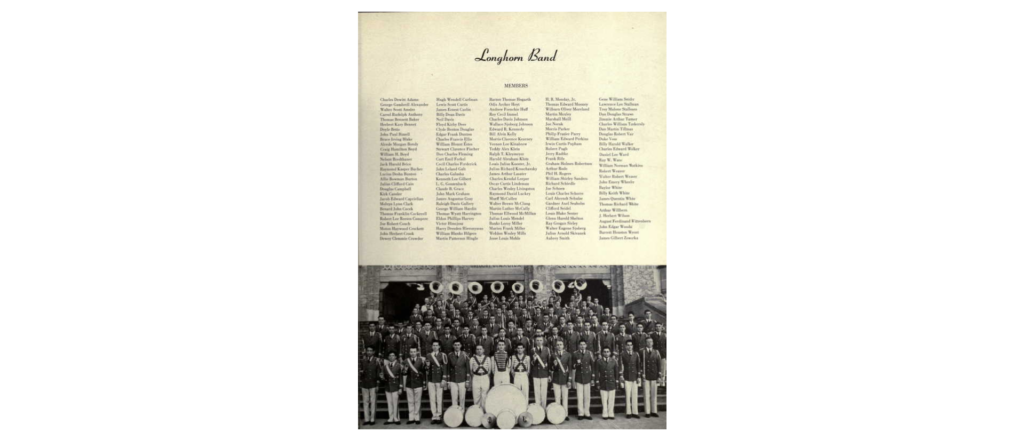

The “Cactus” yearbook shows Louis to be a proud member of the Longhorn Band and the Light Opera Company

Meanwhile, Louis enrolled at the University of Texas and quickly became enthralled with all aspects of college life. But, as anticipated, Uncle Sam came calling. Louis, now living on 22nd Street in Austin, received an Order to Report for Induction on April 15, 1943. He withdrew from college, noting “I was drafted.” His physical noted that Louis was 5’8” and weighed a whopping 137 pounds.

After basic training at Sheppard Field at Wichita Falls, he was set to Army Air Forces Technical School for Radio Operators and Mechanics at Sioux Falls, South Dakota, learning direction-finding by triangulation, Morse code, and how to operate “superheterodyne” receivers. He graduated in December 1943.

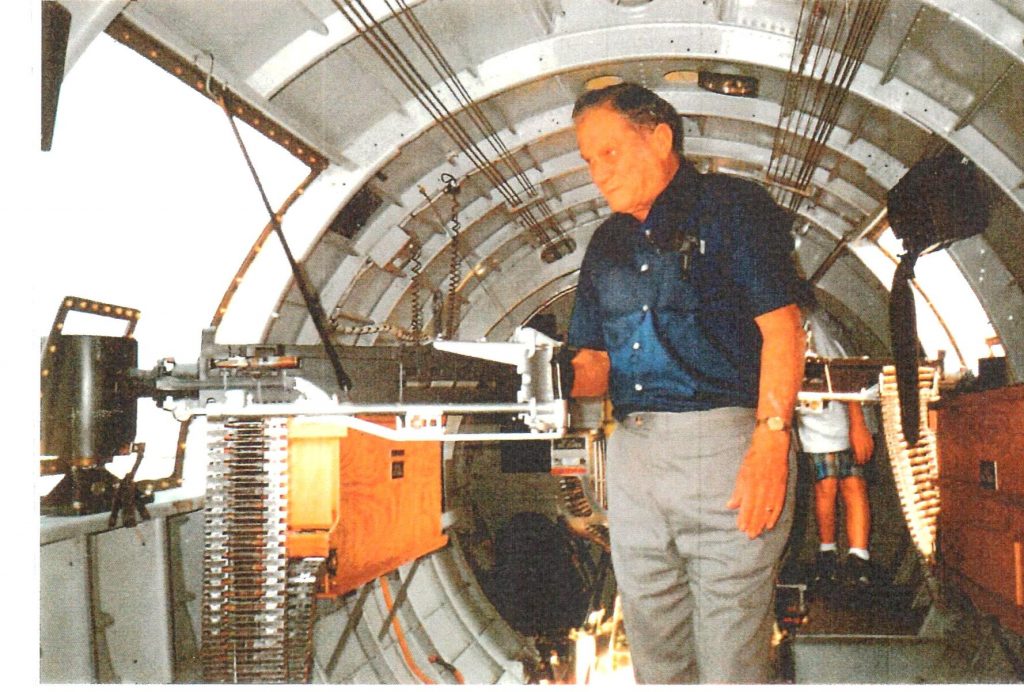

Next stop for crew training: Yuma Army Airfield, Arizona, for gunnery training and a promotion to corporal. Then, as noted in a notebook he kept, are a few of the steppingstones to his assignment with an air crew began: Fresno, California; Hamilton Field, California; Honolulu, Hawaii; Townsville, Australia; and by the end of his war – San Jose, Mindoro Island, Philippines.

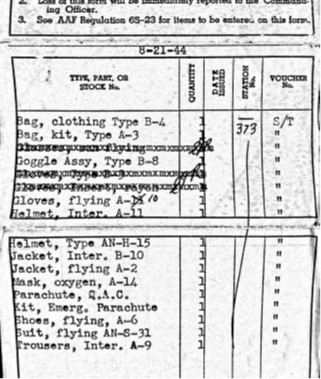

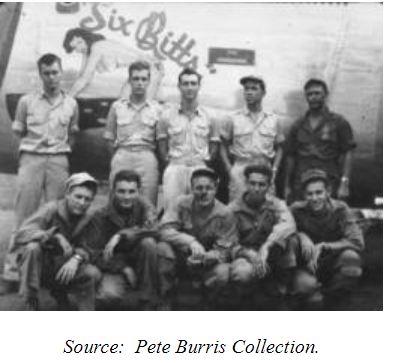

But first, in Walla Walla, Washington, he was issued flight crew equipment, and no doubt told by some supply sergeant that ‘if you lose any of it, you’ll have to pay for it.’

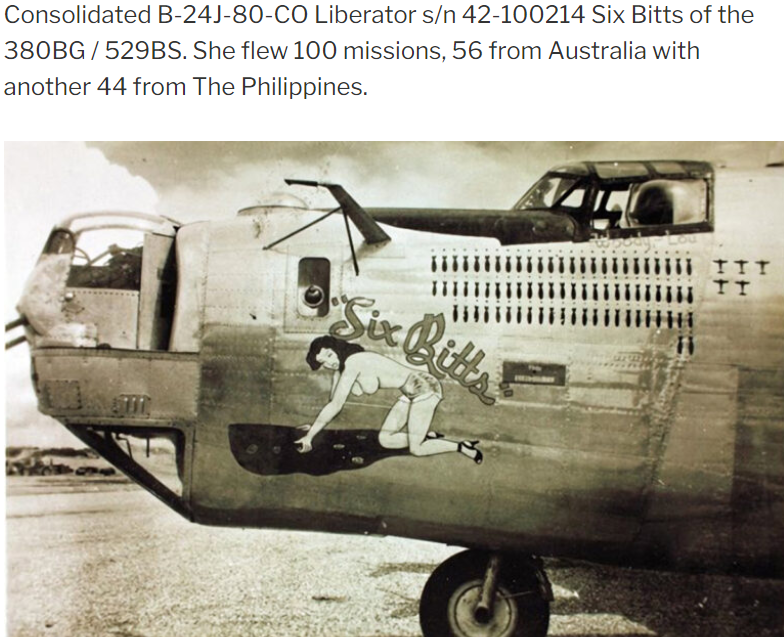

Louis had been assigned to the 529th Squadron, 380th Heavy Bombardment Group. The 380th, proudly called “the Flying Circus,” was assigned to a lesser-known area of the war’s combat against the Japanese- the Southwest Pacific. That theater of operations was vitally important in the Allies’ efforts at defeating the Empire. All, or almost all of its petroleum was produced in that area, originally colonies of Britain and The Netherlands. Louis arrived in Darwin, Northern Australia, and was assigned to a B24-J dubbed “Six Bitts,” piloted by Captain Harry Rollins. He flew most of his thirty-nine combat missions on this aircraft. One production area, Balikpapan, in Borneo, at the beginning of the war, was vital to the enemy. As they evacuated Borneo in early 1942, the Dutch did their best to scuttle the refineries. The facilities were subsequently repaired and by 1943–1944, Borneo had become one of Japan’s main sources of fuel, crude and heavy oil; in 1943, Balikpapan provided 3,900,000 barrels of fuel oil to the Japanese war effort. Fifteen-hour round trip runs started in Darwin and other airfields in Australia’s far north. Early raids by B-24s were costly. When Louis arrived, there were enough fighter escorts that attacking the refineries were less deadly – but hardly safe.

As noted in the 380th Bomb Group’s history: From the end of May 1944 until it moved to Murtha Field, San Jose, Mindoro, Philippines in February 1945, the 380th concentrated on neutralizing enemy bases, installations and industrial compounds in the southern and central East Indies. In April 1945, Far East Air Force relieved the 380th of its ground support commitments in the Philippines. During the month, the group flew the first heavy bomber strikes against targets in China and French Indochina. In June 1945, the 380th was placed under the operational control of the 13th Air Force for pre-invasion attacks against Labuan and on the oil refineries at Balikpapan in Borneo. For nearly two weeks, the Group’s Liberators kept these targets under a state of aerial siege. After the Borneo raids, the 380th flew its last combat missions to Taiwan.

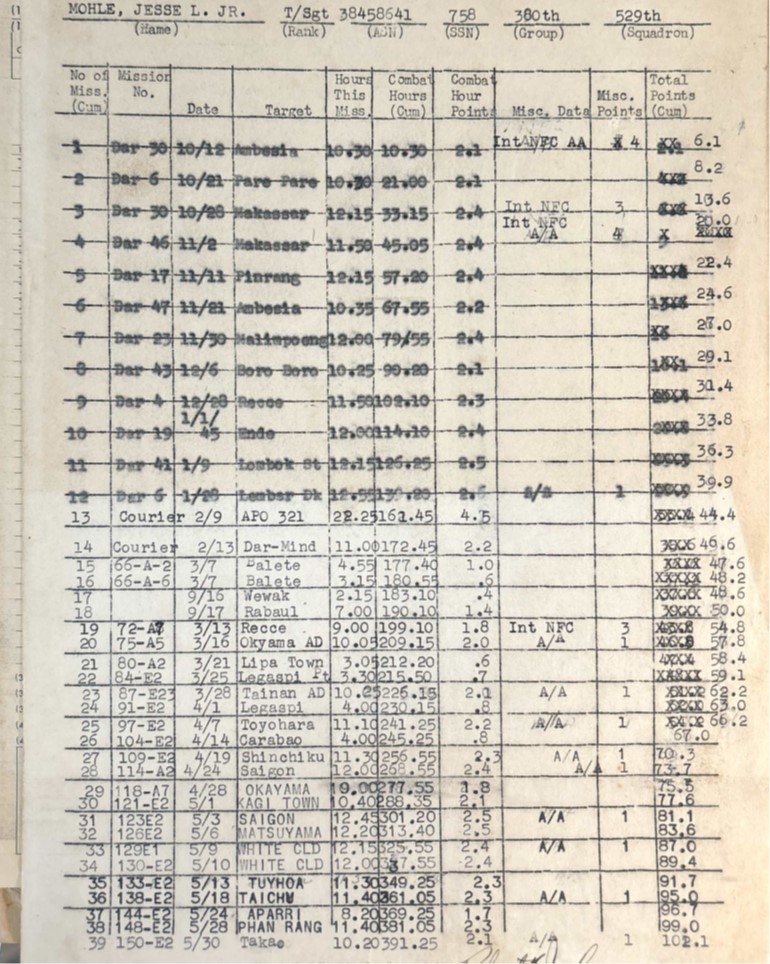

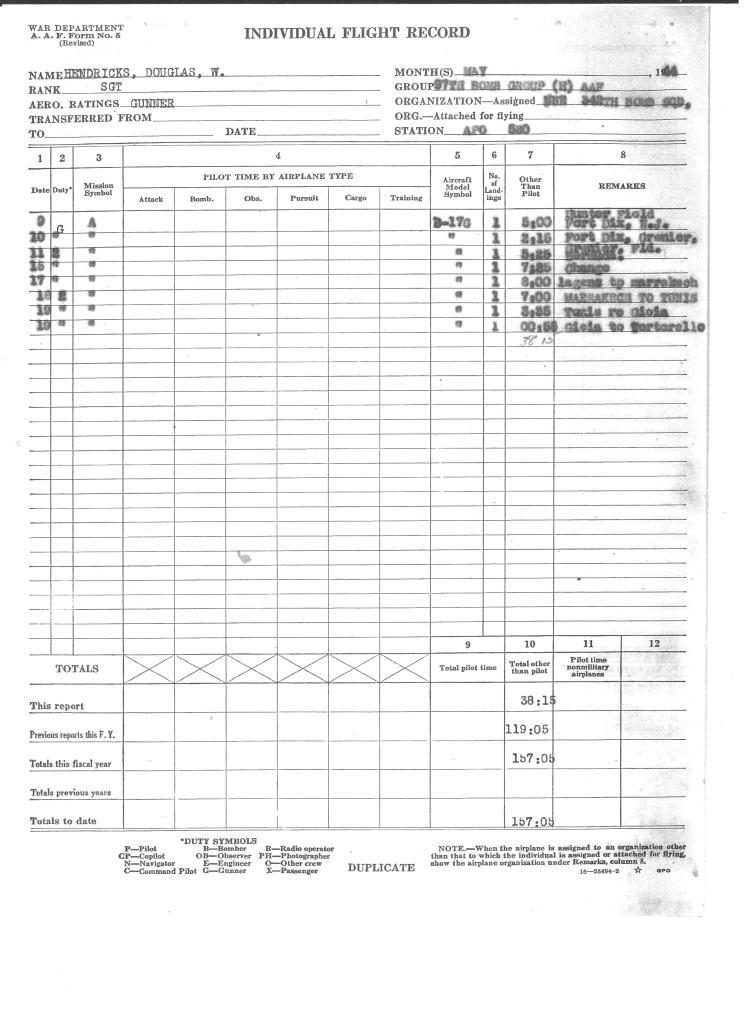

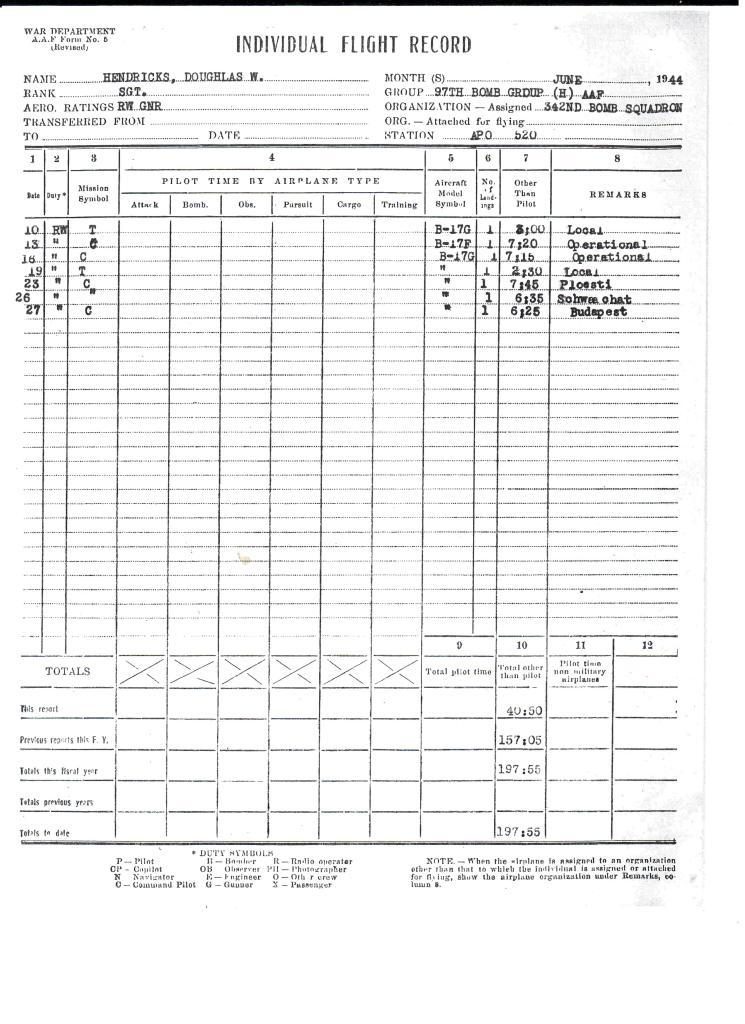

His flight log shows endless hours in a non-pressurized B-24 making bombing runs to Makassar, Pare Pare, Ambesia, and Pinrang on the island of Sulawesi in what is now Indonesia. Bombing runs were made to the Lombok Strait, near the island of Bali. Ende, on Flores Island, and on suspected Japanese naval areas. Rabaul and Wewak, major Japanese naval and air force bases, were hit. In early 1945, the 380th relocated to the newly liberated Philippine island of Mindoro. Louis’ flight log shows bombing runs supporting American forces there. Also, more long over-the-water flights bombing Japanese strongholds in Indochina (Saigon), Formosa, and mainland China.

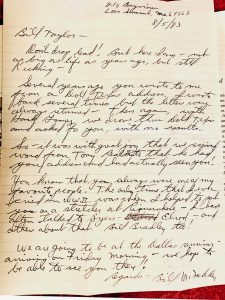

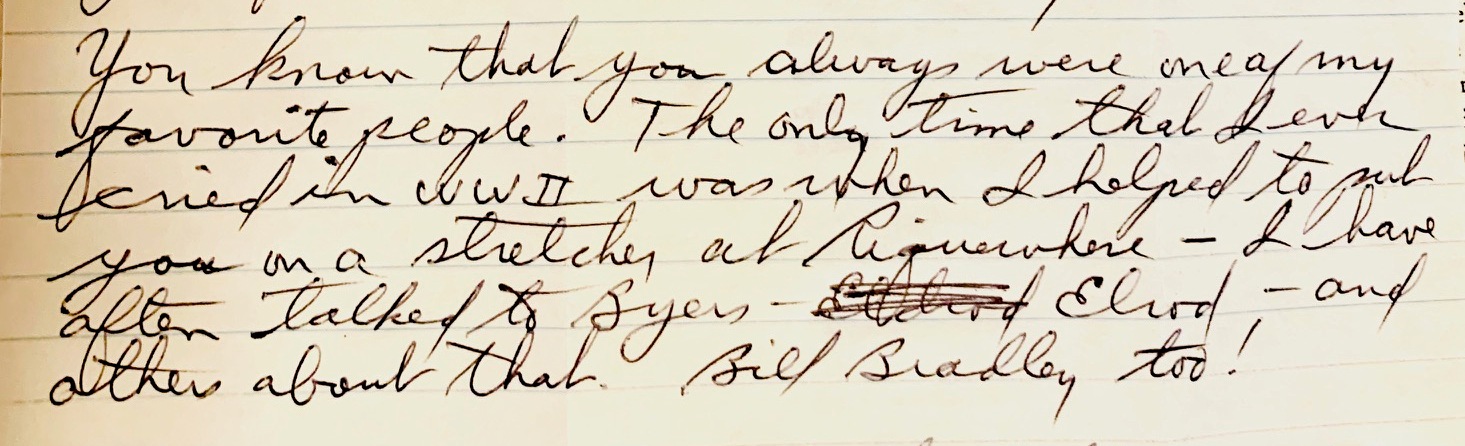

Louis with Pete the Wallaby

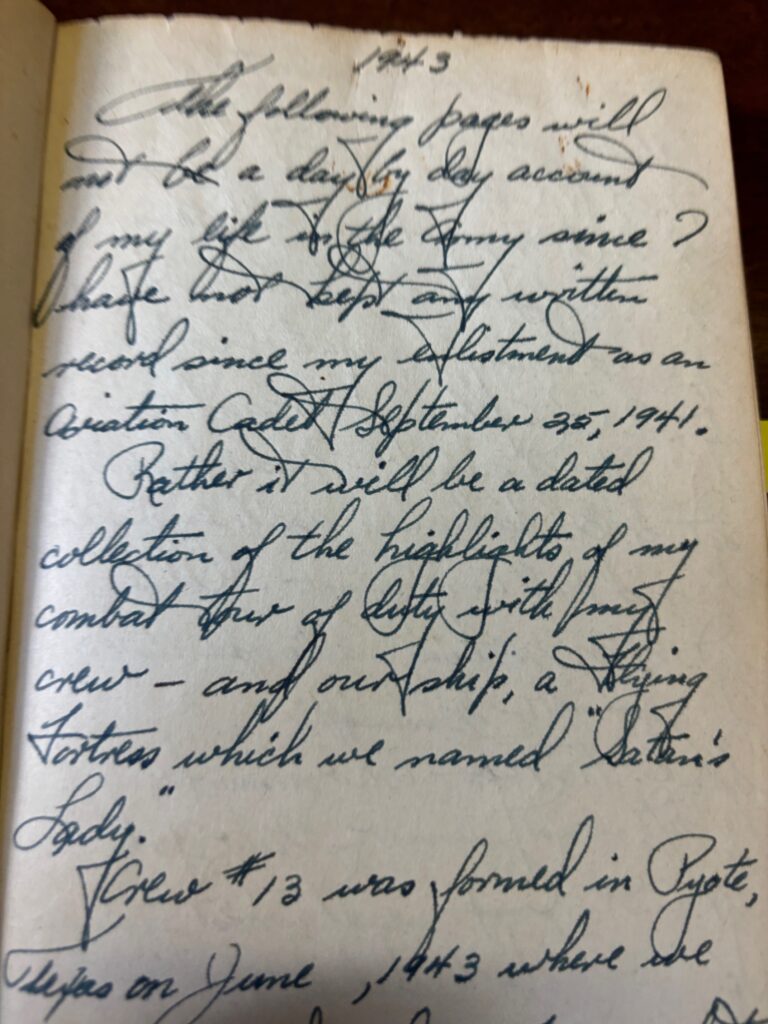

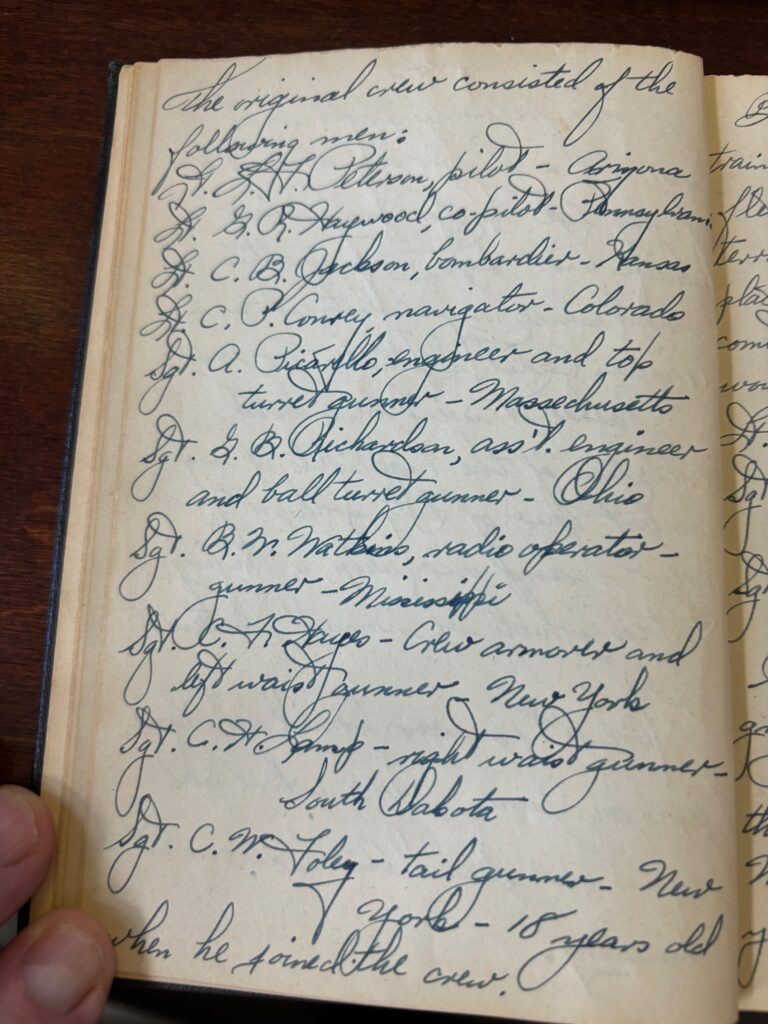

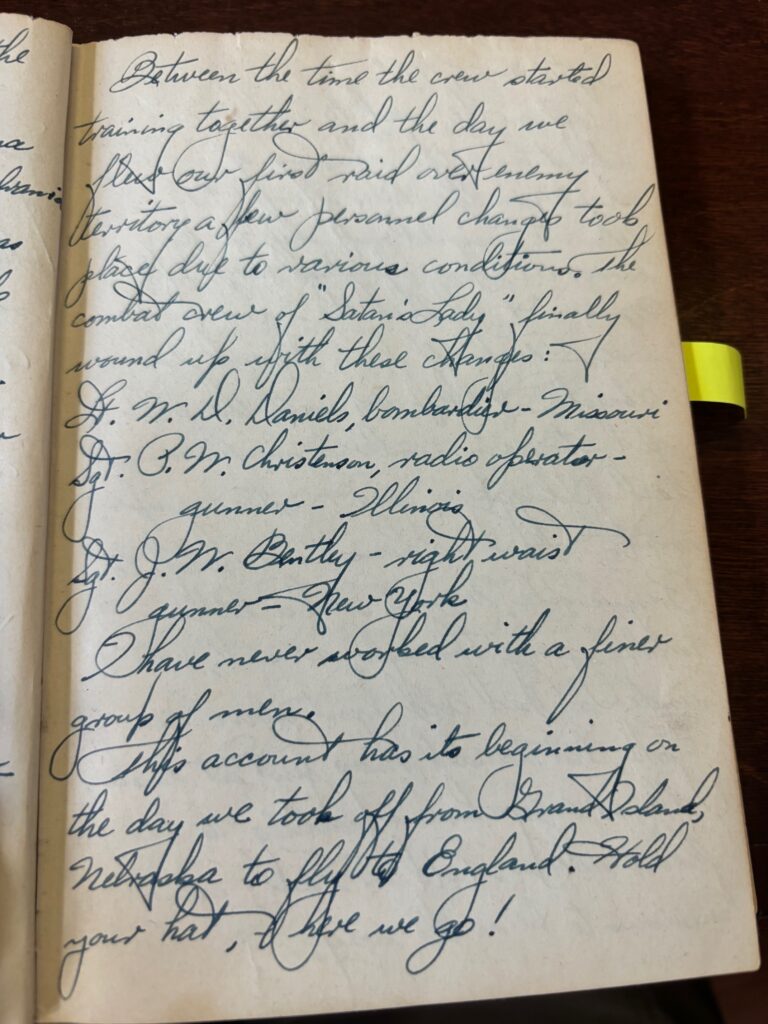

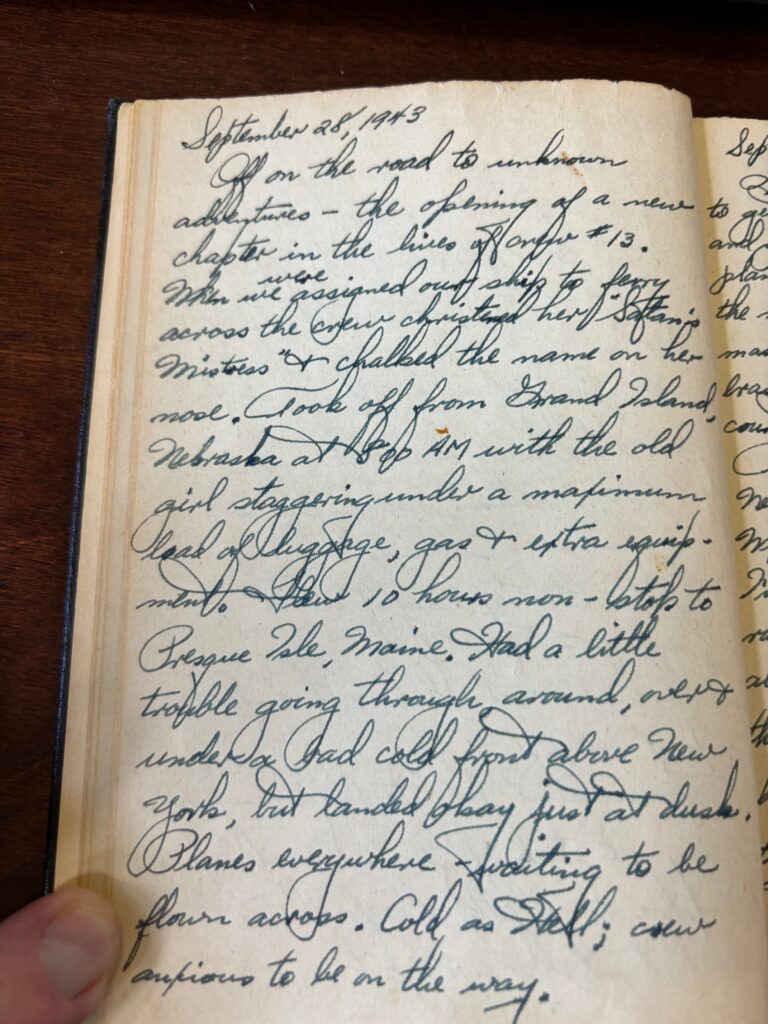

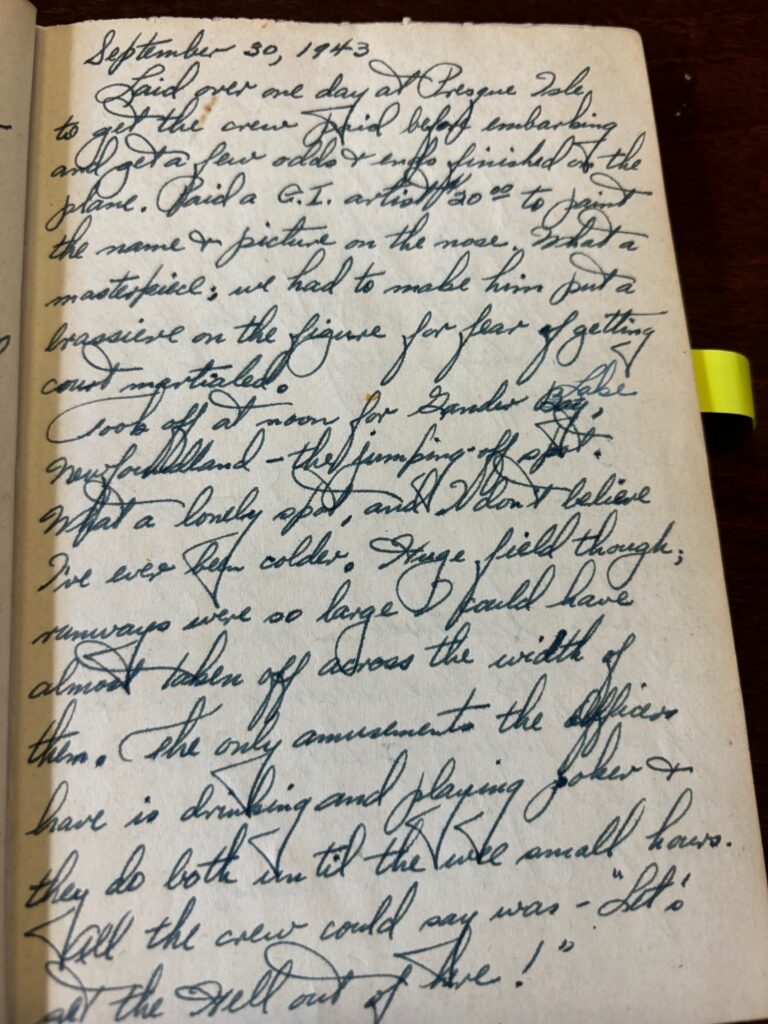

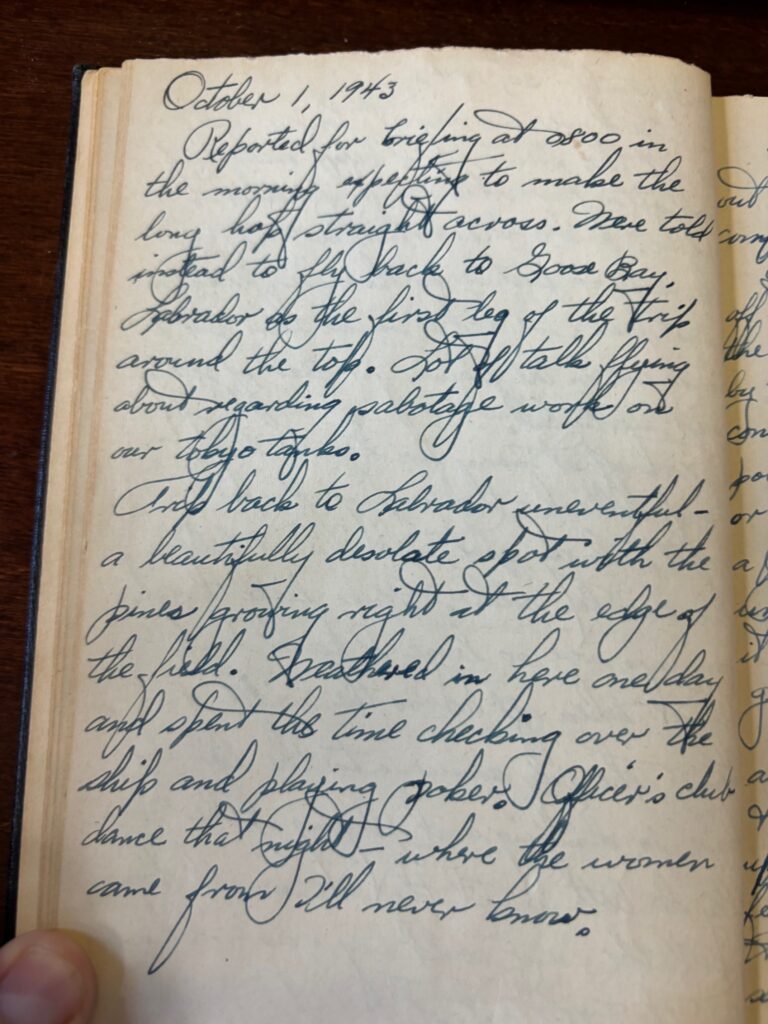

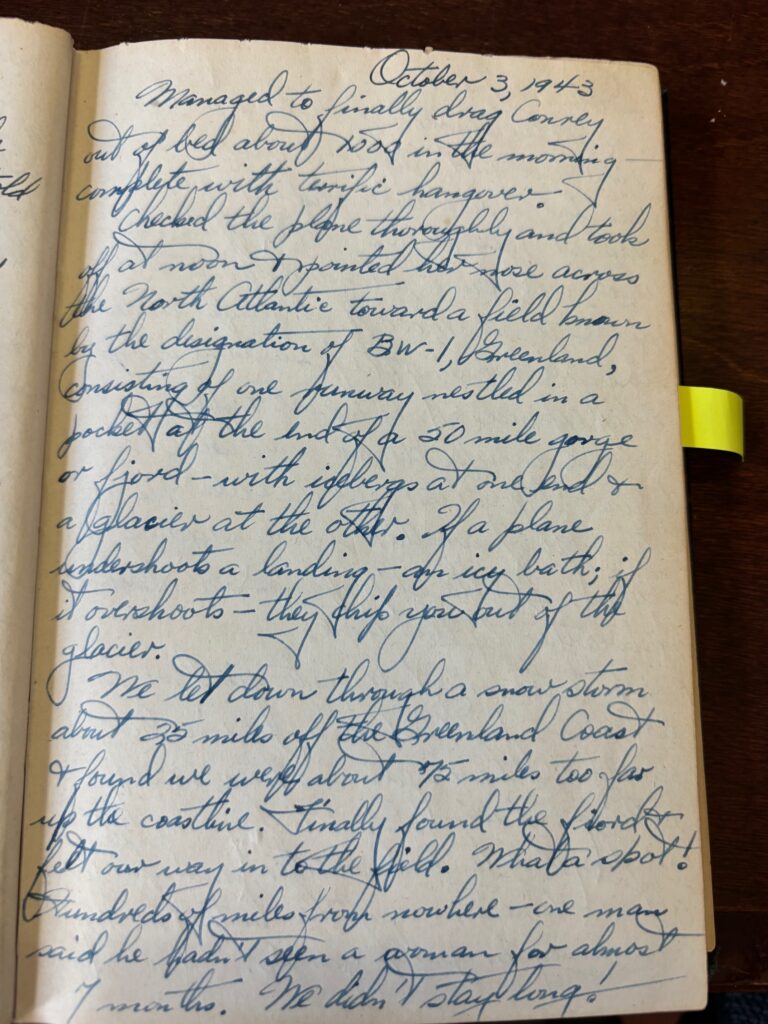

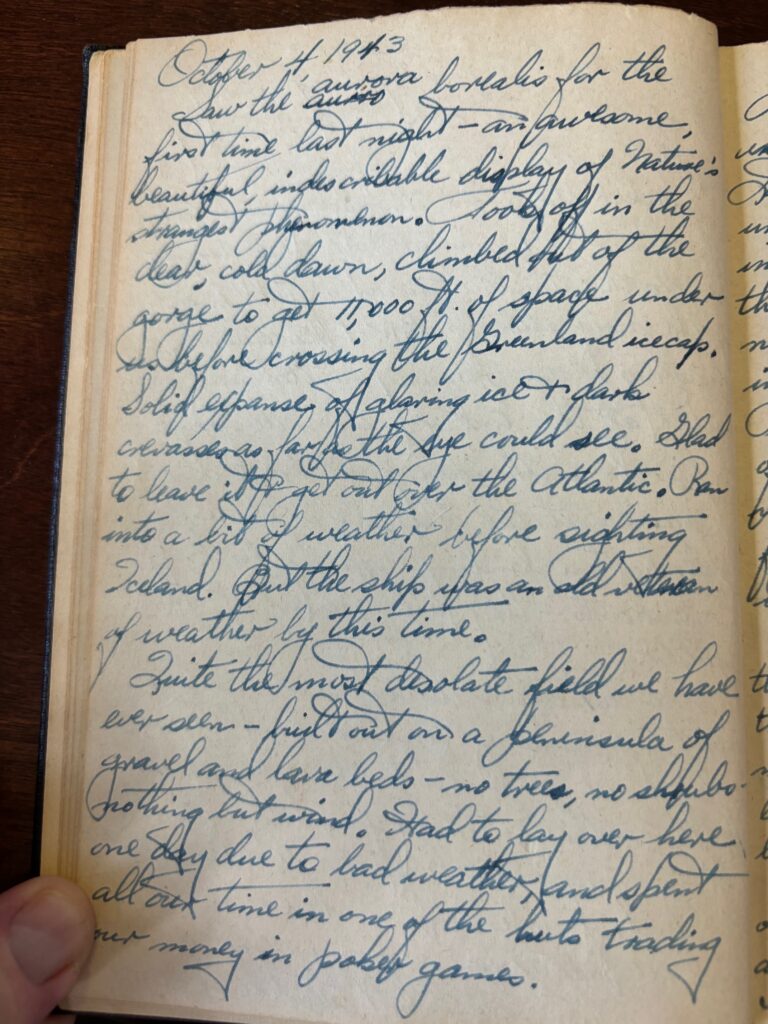

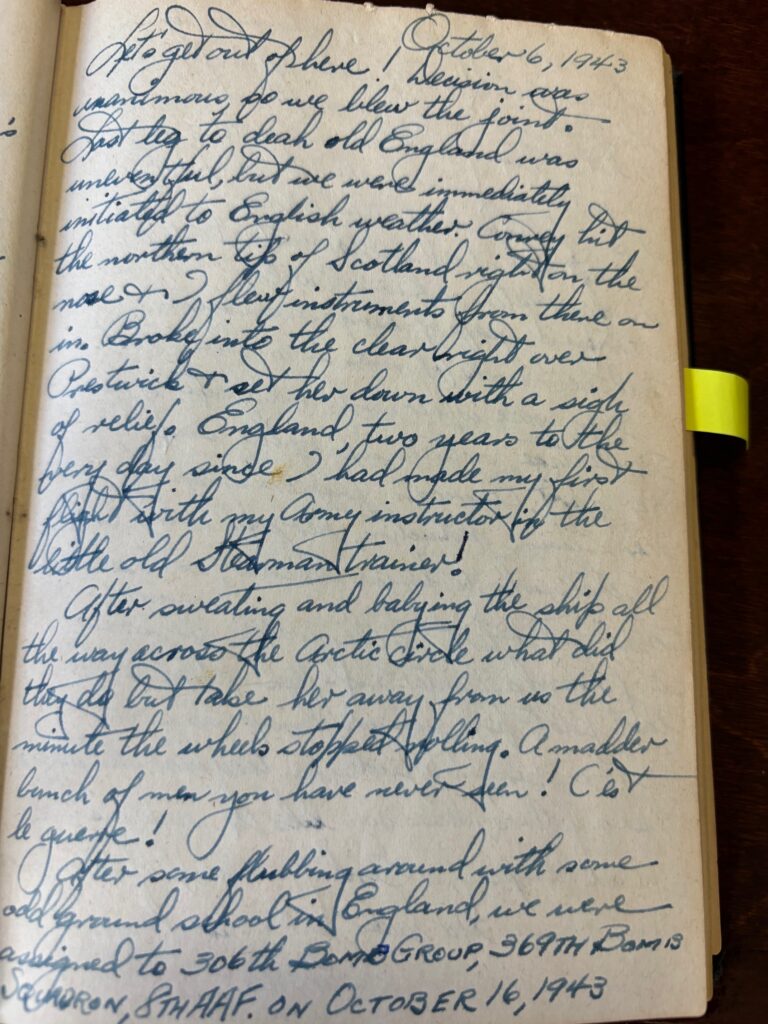

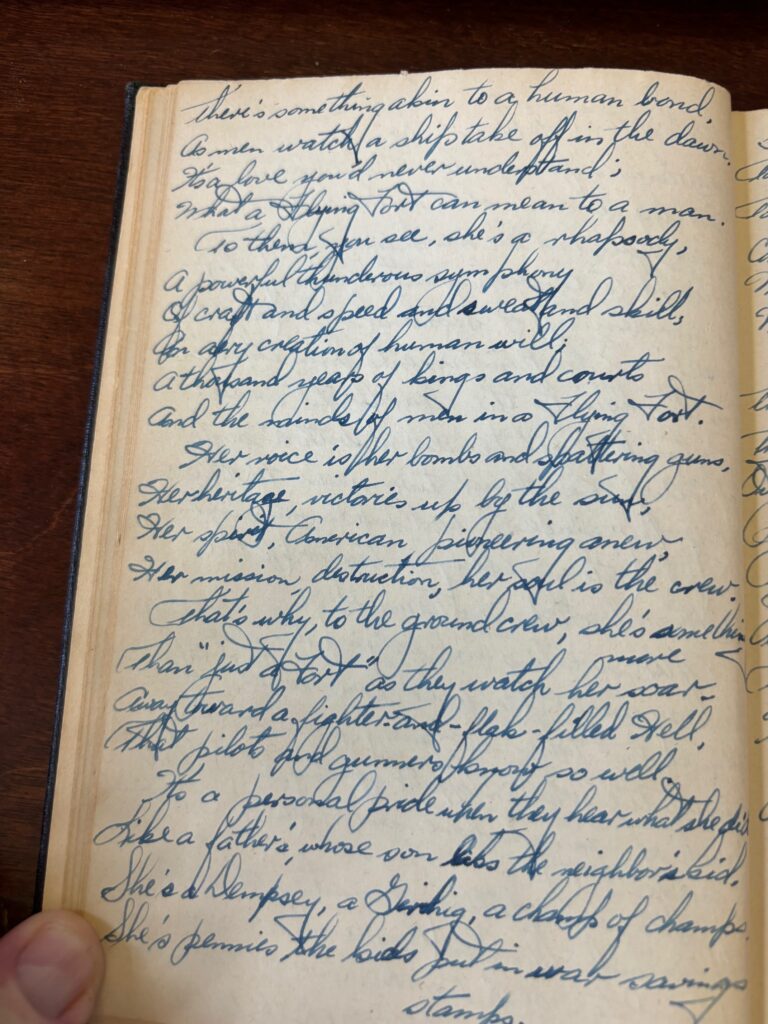

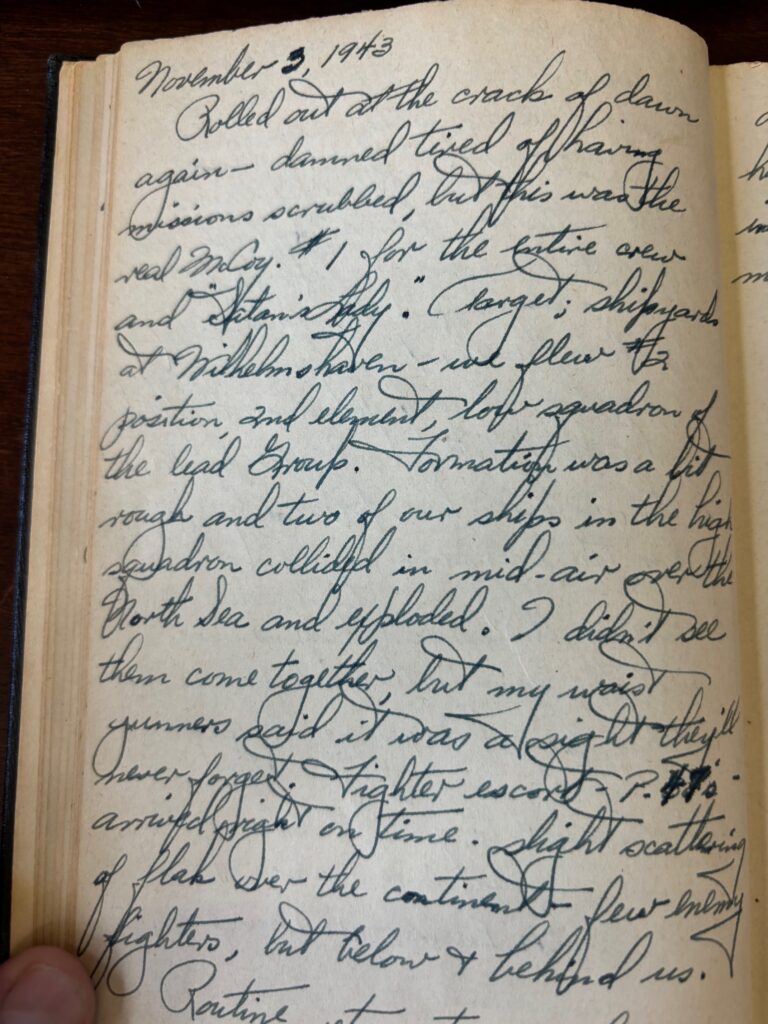

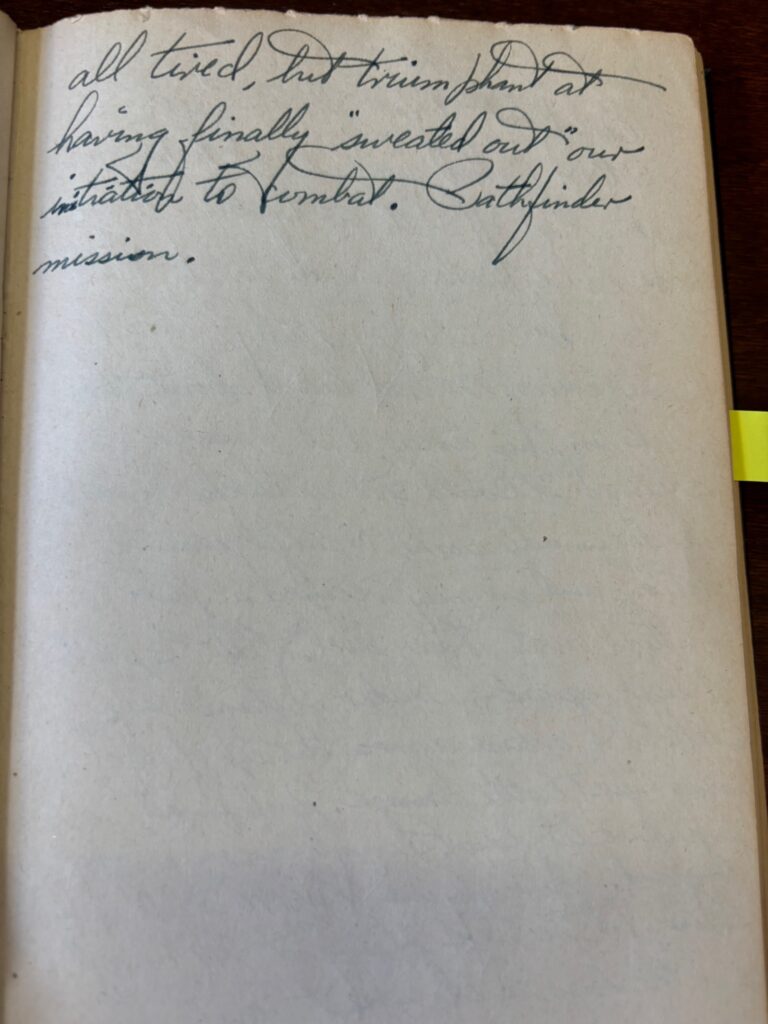

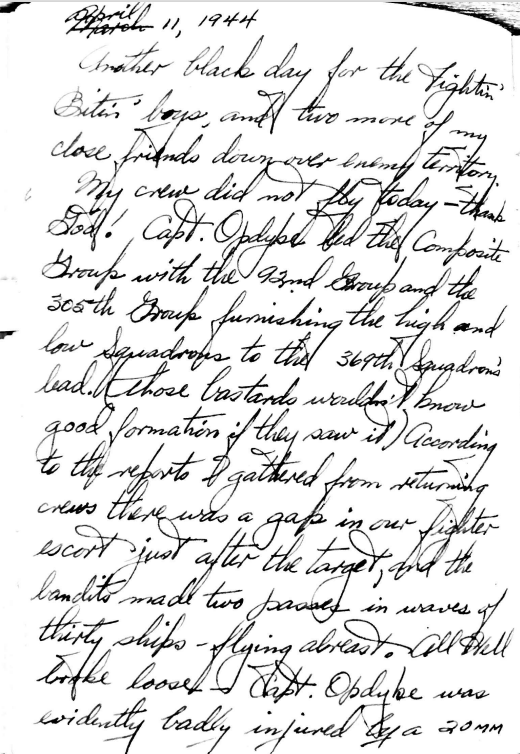

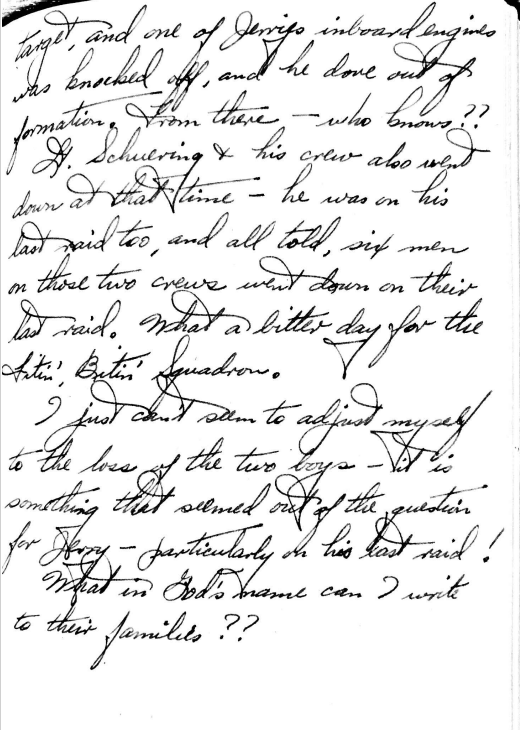

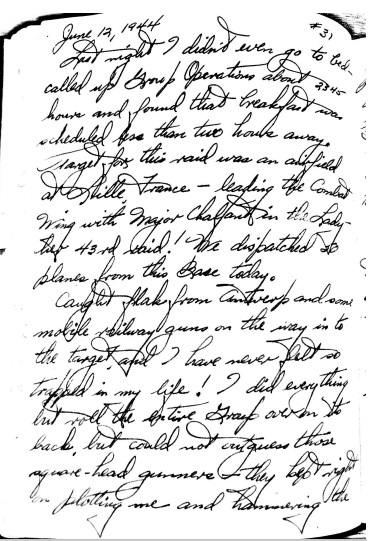

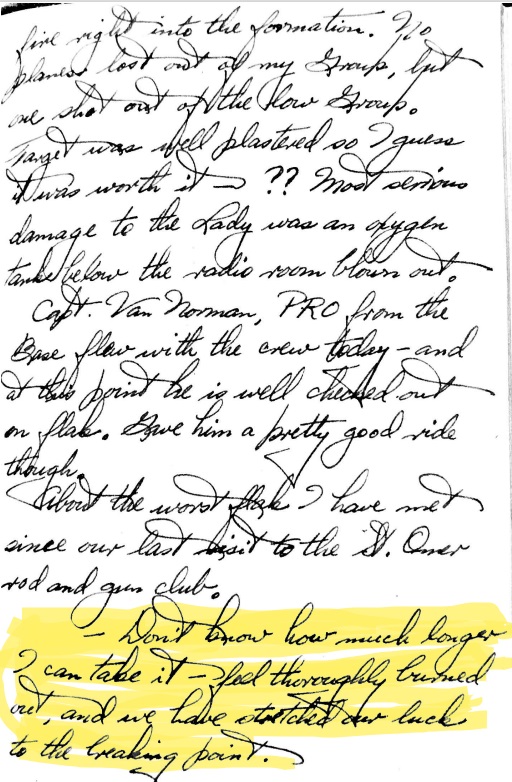

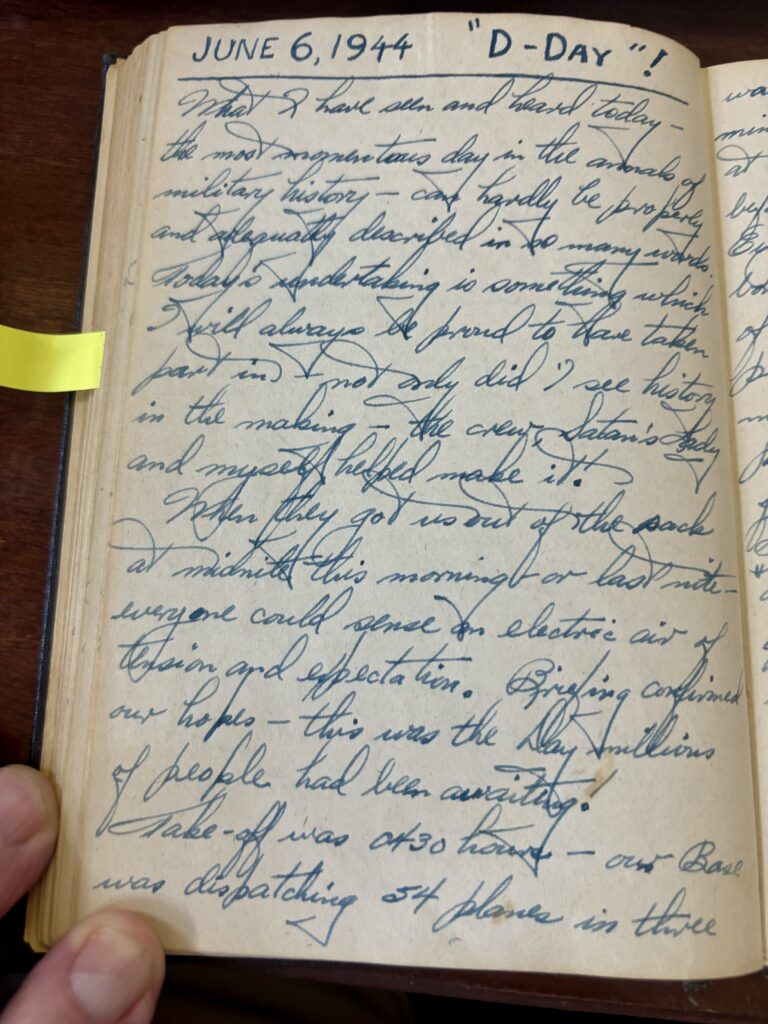

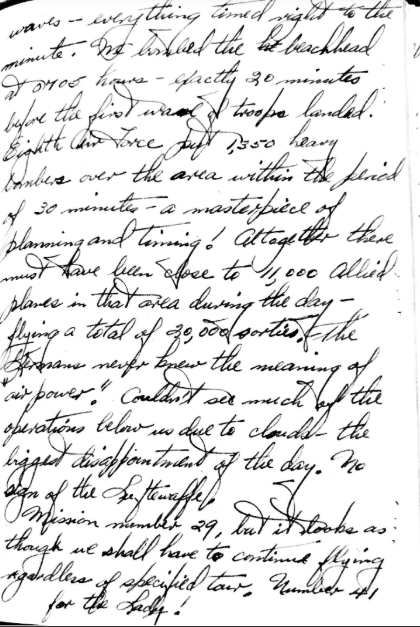

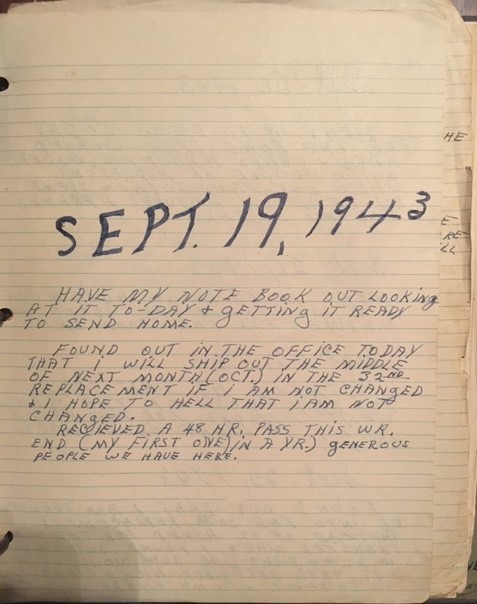

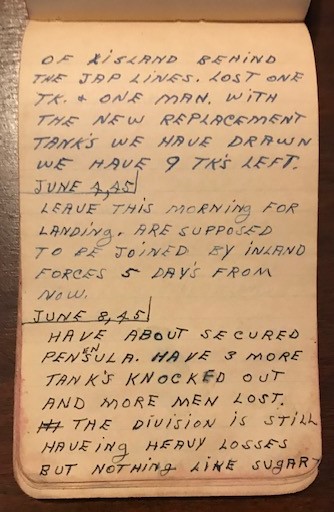

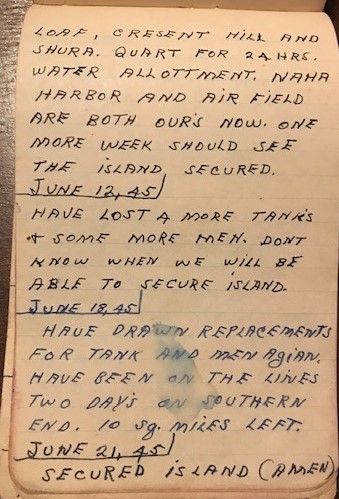

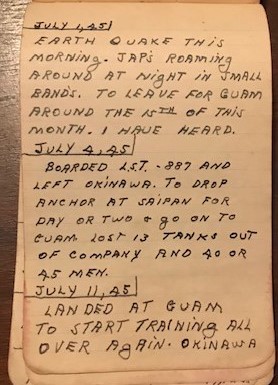

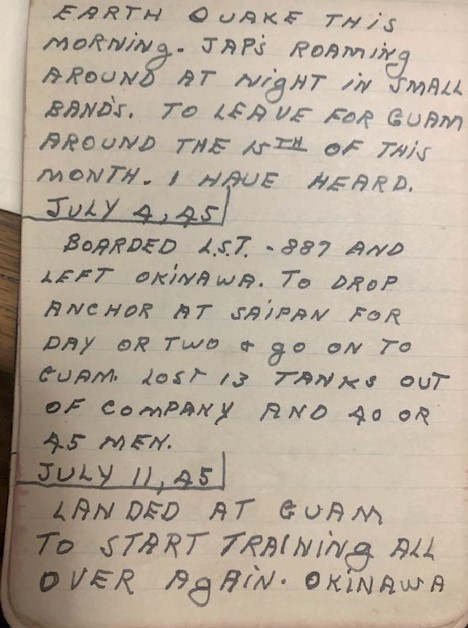

Lucky for us, Louis kept a few photos. He also kept a diary of sorts, showing his optimism about life, appreciation of new discoveries, and lighthearted approach to life. No doubt due to censorship, he kept some entries short, but they show his deep awareness of the lethality of war. Here are just a few of its entries:

September 16, 1944: Our present hobby is a most famous one in the army – eluding a work detail…The jerks here played poker till eleven o’clock last night and I was trying to get some sleep.

November 2, 1944: Got my promotion as you can see [tech sergeant]. A radio man, next to the bombardier, has the best goof-off job in a crew.

November 20, 1944: I’ve been on five missions. I don’t like night missions. I went on a ferry trip taking buys out that coming home. On one mission I was sitting in the waist by the tunnel guns and my parachute harness was hanging over my head. When the bomb-bay doors came open the harness blew down around my neck like a horse collar. It really scared me for a minute.

December 19, 1944 (on leave in Australia): Just got back from Adelaide and what a town! I went out with four different girls while there. You’d be surprised the way you have to knock the girls off of you.

December 29, 1944: I now have over 100 hours. For excitement, go out in bad weather, lose an engine, have a bad gas leak on another, salvo the bombs, have instruments go out and you’ve got something. We did.

February 20, 1945 (after the 529th move to Philippines): …Last night we were waked and guards put out because there were supposed to be [Japanese] near. Didn’t sleep much. Today we were really armed when our detail went out.

March 31, 1945 (after a bombing mission over enemy held Formosa): I’ve got about 225 hours now, part of it over Formosa. They can shoot pretty good there.

June 20, 1945: (censored [I suspect a curse word]) Lt. Long, Lugin, Martin and Nicks were shot down a while back (censored [again, I suspect a word showing Louis’ anger or upset]).

Finally, it was time to come home from the war. He made it back to Austin in January 1946, and immediately re-enrolled at the University of Texas, joining the Glee Club and Ex-serviceman’s club. Upon graduation, he returned to his beloved hometown and continued as an integral part of its life.

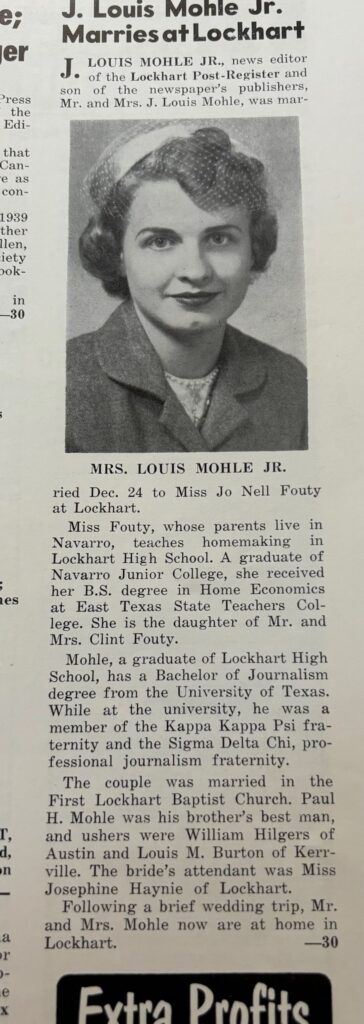

He became the Post Register’s editor. In 1953, he met a beautiful LISD schoolteacher, Jo Nell Fouty. She became his wife and best friend in 1954. Louis and Jo Nell had two sons, Terry and Clint, and later adopted a daughter, Kay Lynn (Chamness).

He immersed himself in all aspects of Lockhart. He probably went to every Lockhart Lion football game from the 1940s until 1980. Son Clint loved the great seats in the press box. He witnessed Lockhart win some great games and had stories to tell.

He was instrumental in getting Little League Baseball in Lockhart. He was in fact the first player agent. He made sure he saw and verified that he saw all the players’ birth certificates and they were the correct age to play in Little League. He attended every event of local interest and importance and wrote about it for the paper.

In 1958, he acquired the Post Register from his father, and sold it to Dana and Terry Garrett in 1980.

Louis Mohle helped make Lockhart and Caldwell County a great and friendly place to live and work. He sang at weddings and funerals, was the President of the Lockhart Chamber of Commerce, President of the South Texas Press Association, and attended the First Christian Church, where he was an elder and choir leader. He led the singing at every Kiwanis Club meeting for decades.

Doug Foster recalls Louis’ great joke he played on his dear friend, Maxine Goodman. Maxine became mayor of Lockhart. When she showed at an function where Louis led the singing, he would immediately lead the audience in “The Old Gray Mare; She Ain’t What She Used To Be.”

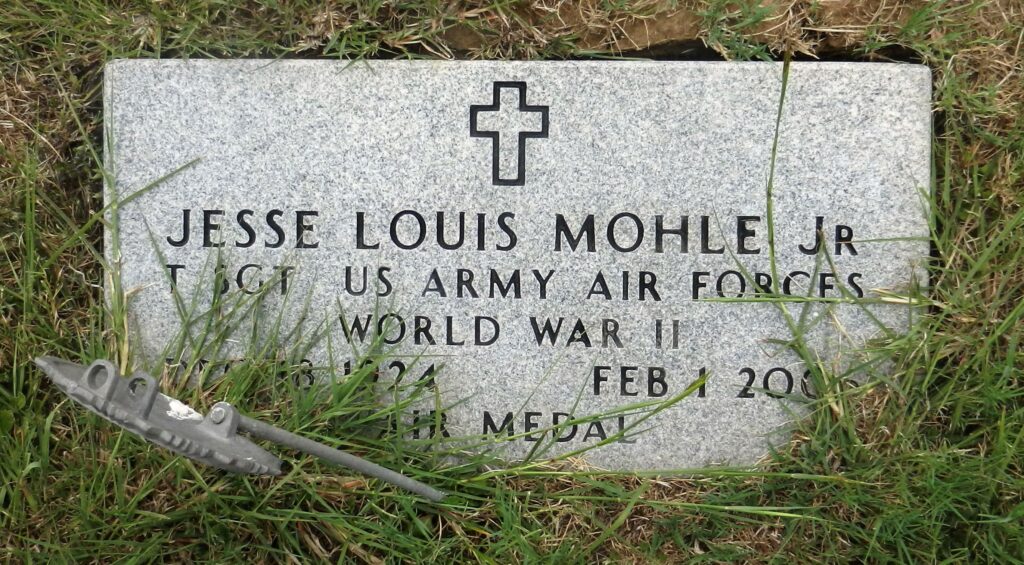

He always had a smile and friendly word for everyone he met. He and his family were and continue to be a part of what makes America great. Louis passed away in 2006. He exemplified the best of the Great Generation. He should not be forgotten.

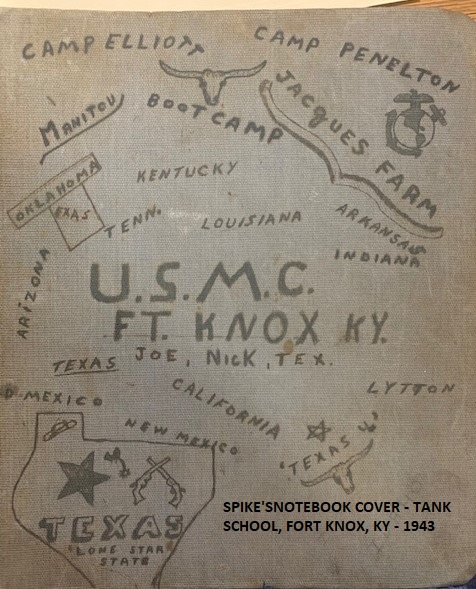

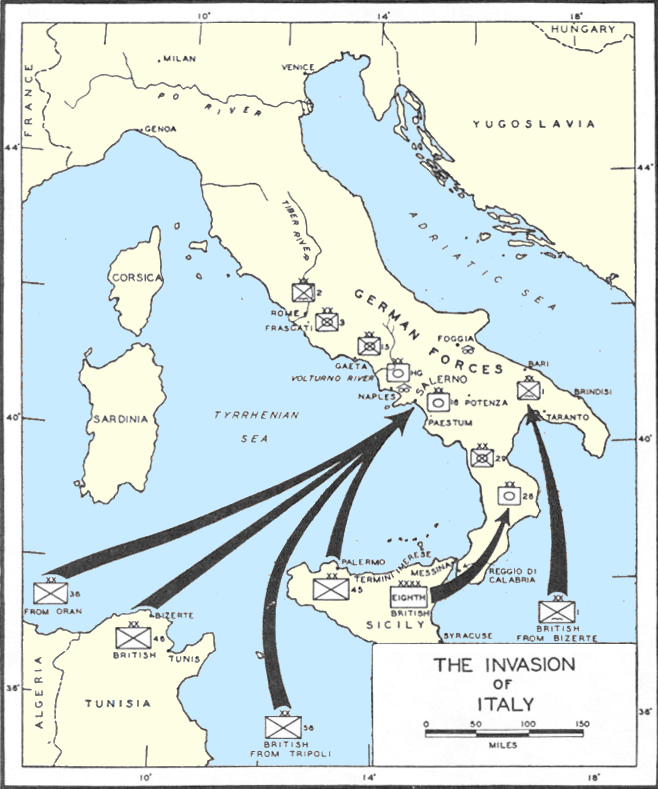

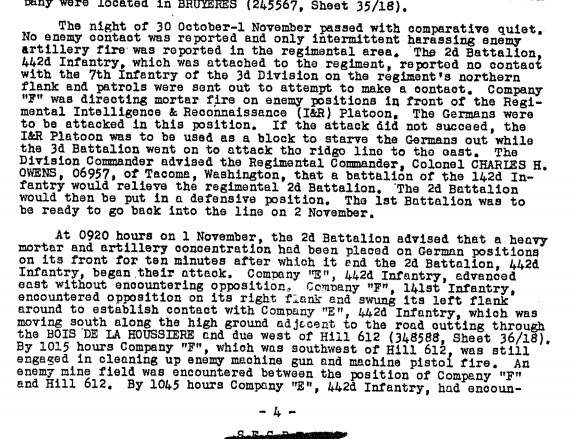

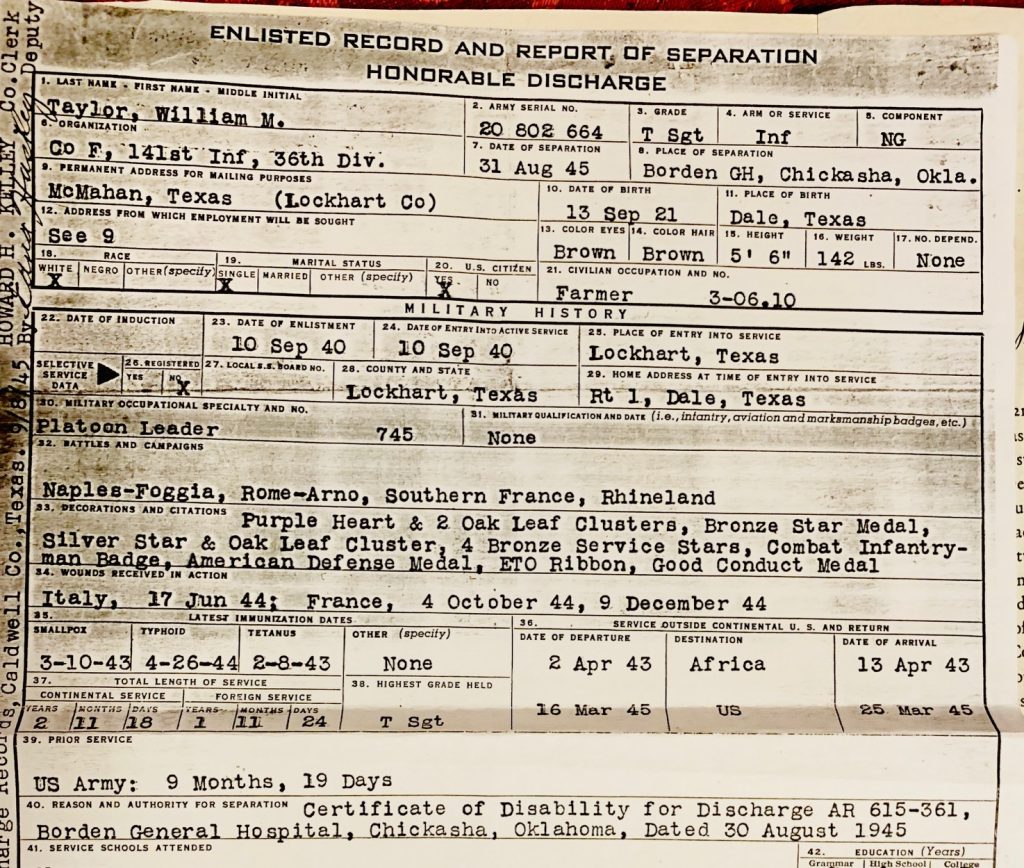

encouraged by older brother Bauzzle, on September 10, 1940, he enlisted at Lockhart in the Texas National Guard’s Company F, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th “Texas” Infantry Division.

encouraged by older brother Bauzzle, on September 10, 1940, he enlisted at Lockhart in the Texas National Guard’s Company F, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th “Texas” Infantry Division.

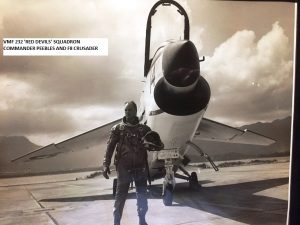

1954. Duty stations included Kaneohe Marine Air Station in Hawaii. In 1959, he became squadron commander of VMF 232, flying F8 Crusaders. In 1967, Colonel Peebles served in Viet Nam as air officer attached to amphibious operations.

1954. Duty stations included Kaneohe Marine Air Station in Hawaii. In 1959, he became squadron commander of VMF 232, flying F8 Crusaders. In 1967, Colonel Peebles served in Viet Nam as air officer attached to amphibious operations.