PATRICK MCGREAL ARMSTRONG, JR.

Patrick McGreal Armstrong, Jr. was the second child of Patrick Sr. (“Pat”) and Elizabeth Martha (Strong) Armstrong. He was born on March 2, 1920 in Forth Worth, Texas. He had an older sister, Bennie, and four younger siblings, Stephen, Mollie, Margaret, and Churchill. Pat was born in Heidenheimer, near Waco, in 1896 and was in the oil business in some capacity for much of his adult life. As such, he and his family moved often, following the oil plays in various parts of Texas. His World War I draft card showed him to be living at 100 S. Thompson Street, Houston, Texas and working for Texas Supply Company in Beaumont. At the time of Patrick Jr.’s birth, he listed his occupation as a driller. The family lived in Wichita Falls in 1921 when Patrick’s younger brother Stephen was born. In 1923, the family was living in Houston. By 1929 the Armstrong family had moved to 123 Monroe Avenue, San Antonio, and Pat was manager of ABA Oil Company. By 1930 he had become an independent oil operator. In 1934, the East Texas boom brought Pat to Tyler. At some point in the late 1930s the family moved to Luling. The family residence fronted State Highway 29 (the road to Lockhart). In Caldwell County Pat’s finances took a downturn, and in 1940 he filed for bankruptcy. The federal court in Austin granted the bankruptcy on January 6, 1941, and the Post Register gave official notice to his creditors soon thereafter.

Pat moved back to San Antonio after the bankruptcy. He, Elizabeth and the younger children lived at 406 Dunning Avenue. He started a new business – Armstrong Iron & Salvage Company. He would later become a Methodist minister working with Goodwill Industries.

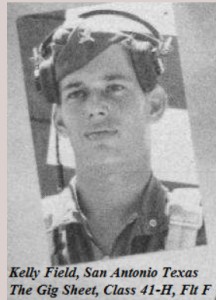

The family was still in Luling when Patrick, after completing one year of college, enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and was accepted for flight training. His initial training was in the San Diego, California area. He then completed his advanced flight training at Kelly Field outside San Antonio. He graduated with Class 41-H on October 31, 1941, and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant. He was assigned to the 36th Pursuit Squadron, 8th Pursuit Group. Recently transitioning out of obsolescent P-36s into P-40s, the unit trained in anticipation of a war in Europe. The Group’s mission changed with the sneak attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. After a short time of flying defensive cover over New York City the 8th Pursuit Group (which consisted at the time of the 35th and 36th Pursuit Squadrons) entrained to San Francisco in early January, 1942.

The suddenness of the attack and the swiftness of the Japanese advance across the Southwest Pacific caused substantial panic. The American Territory of the Philippines was quickly becoming a lost cause, and plans to sail there were scrapped. Sparsely populated Australia had by this time sent most of its able-bodied men to fight the Germans and Italians in North Africa and the Mediterranean. There was little to stop a Japanese advance into that vast and under-populated country. Hurriedly, the Americans cobbled together assistance to the beleaguered Aussies. The 8th Pursuit Group sailed from San Francisco on February 12, 1942 for Northern Australia on the United States Army Transport (USAT) Maui.  A passenger steamship built in 1917, it had been purchased by the government in late 1941. The crossing took 24 days. Arriving at Brisbane on March 8, 1942, the Group began training on recently assembled Bell P-39 Airacobras. It then moved north to Townsville.

A passenger steamship built in 1917, it had been purchased by the government in late 1941. The crossing took 24 days. Arriving at Brisbane on March 8, 1942, the Group began training on recently assembled Bell P-39 Airacobras. It then moved north to Townsville.

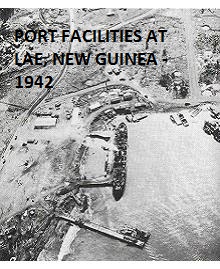

It is impossible to overstate the Allied concerns about the Japanese juggernaut in late 1941 and 1942. The Emperor’s forces had sliced through supposedly impregnable defenses at Singapore, taken Hong Kong, trapped American forces in the Philippines, and seized islands all over the Pacific. Somewhat surprised by the speed of their advance, the question for the Japanese high command was where to go next. It was decided that three axes of advance be made. One would move into the Solomon Islands, Fiji and Samoa to cut the supply route from the United States to Australia. The second would strike toward Midway and Hawaii, and the third would take control of the huge and virtually unexplored island of New Guinea, in anticipation of an eventual move into Australia. It was deemed necessary also to protect Japan’s huge naval facilities at Truk and Rabaul. Papua New Guinea, the southern half of the landmass was an Australian-administered territory. Both sides realized that control of its coastline was critical. Bombing of the territorial capital of Port Moresby began in late February, 1942. Japanese forces began unopposed landing at Salamaua and Lae on its northern coast soon thereafter. Lae, known because it was the last departure point for Amelia Earhart in her ill-fated 1937 attempt at circumnavigating the globe, was quickly turned into an advance airfield. The Japanese planned to ship men around the southern tip of New Guinea and take Port Moresby. From there it was a short hop to the Australian mainland. (This attempt would later be thwarted by a carrier battle in the Coral Sea, and the incredible bravery of Australian forces which prevented the Japanese army from crossing the New Guinea’s forbidding Owen Stanley Mountains)

Australian forces began reinforcing the Port Moresby area as the Japanese forces built up its forces for an anticipated attack.

The 8th Pursuit Group’s ground and support units sailed to New Guinea on April 20, 1942 and its three squadrons’ (it had added the 80th Pursuit Squadron) P-39s flew up between April 26th and April 30th. The 36th Pursuit’s new home was Seven Mile Drome, a dirt strip outside of Port Moresby. To say that conditions were primitive would understate matters. Torrential rains, sudden and violent storms, exposure to malaria-carrying mosquitoes, and repeated bombings by the Japanese made life precarious.

Air combat in P-39s against highly trained pilots and better Japanese aircraft shortened lives as well. The P-39 was of innovative design, with a tricycle landing gear, and an Allison V-1710 engine directly behind the pilot. Its export version, the P-400 would prove an effective tank buster for Soviet forces. But the P-39/400 was often an inadequate match against more advanced fighters in dogfights. Plagued with oxygen system problems and a low service ceiling, it could not reach high flying enemy bombers. Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, Saburo Sakai and other Japanese aces racked up impressive kill numbers with A6M2 “Zeroes” when P-39s were used as interceptors.

The 8th Pursuit’s units went into combat immediately, primarily defending the Port Moresby airfields. On May 4, 1942, Patrick Armstrong piloted a P-39D-BE, aircraft number 41-6971 in support of a raid against the enemy facilities at Lae. He was not seen again.

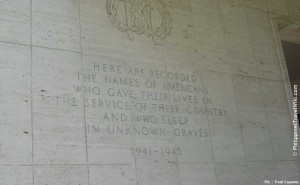

Although an official ‘finding of death’ was not made until December of 1945 it is almost certain that Patrick was the first Caldwell County casualty of World War II. His body was never recovered. He is memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing, American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines.

Patrick was twenty-two years old.

Todd, Hi, Pat M. Armstrong here in Lexington, KY and nephew of Pat…this is a really nice, well-written history. You have obviously done a comprehensive job researching the events of this tragic story and I appreciate your doing this kind of thing on his behalf. We consider him a most selfless American patriot and hero, so this kind of remembrance is both necessary for Texans, all Americans, and family members. Again, I am impressed with the accuracy of your research and your ability to convey that in this historical narrative. Bennie, however, was a sister and not a brother–the name derived from a maternal great-grandmother, Benjamine Churchill Jones. My father was Stephen, also a World War II fighter pilot. Additionally, my research (talked to ace Lt Don McGee and people involved with searching for wrecks in the Pacific) is that the Japanese recorded not official shoot-downs of American planes in New Guinea on 4 May 1942. That would indicate a higher probability (unless he was shot down but went unconfirmed by the Japanese) of a mechanical problem or possibly loss of situational awareness that caused his death. Our family remains hopeful that some day he and his plane will be found to put further closure to this story. Thanks again for your tremendous effort here for Pat and all Americans. Sincerely, Pat M Armstrong, Major, USAF (Ret) 859-940-4203

Todd, sorry for the lousy proofreading. Please change my comments if you can–thanks!

Changes:

Line 7– Delete the word “both”

Line 15– Change “not” to “no”

Pat: Just published book about all those who died. I missed your suggested edit, alas, so still put him down as being shot down. In my next edition (I’ve printed 100 copies so far) I’ll make the changes….

Again, thanks.

Pat’s older sibling, Bennie, was not a man but was Bennie Elizabeth, my mother who married Jim Cummins.

Thank you so much for this article. Patrick was my Uncle although I never met him. Our family still has all the letters returned marked Missing in Action. My mother, his sister, gave DNA to JPAC before her death so if he is recovered his remains can be identified.