WILBUR OTTO (SONNY) SALGE

by Todd Blomerth

Wilbur Otto “Sonny” Salge was born on September 30, 1923. He went by “Sonny” and was your typical small town kid. While at Lockhart High School he played football and was co-captain with Alvin Riedel of the Lions football team his senior year. He graduated in 1942, and told his sister Dorothy (Norman) that he just wanted to get out of high school. He knew he was going into the service and didn’t make too big of a deal about his grades. His sister said he didn’t want to wait around to be drafted, so he enlisted in the Marine Corps.

Sonny was the son of Otto and Ella (Hartung) Salge. Otto was a World War I veteran. The Salge family lived at 606 Wichita Street in Lockhart. After high school, Sonny married Mary Holman. Like so many wartime marriages, this one was interrupted almost immediately by the realities of life. He was mustered into the Marine Corps on April 16, 1943, and shipped to Camp Elliott, California for training. While there, Sonny excelled, and was the honor graduate of his platoon. Initially in the infantry, he was later made part of a mortar section.

Sonny was assigned to Company L, Third Battalion, Seventh Marine Regiment. The Seventh was part of the First Marine Division. Shipped overseas in October of 1943, he was one of many freshly minted Marines filling the depleted ranks of “The Old Breed.” The First Marine Division had fought heroically on Guadalcanal, and then was returned to Australia to refit. It had lost thousands to death, wounds, combat exhaustion (the term used at the time for psychological issues arising from the stress of combat) and tropical diseases. After refilling its ranks, the Division was made part of Operation Cartwheel, an Allied plan to isolate the huge Japanese garrison at Rabaul. The 3/7, as the Third Battalion of the Seventh Marines was commonly designated, was part of the First Division which landed on Cape Gloucester on the island of New Britain on December 26, 1943. In a slogging jungle campaign, the division destroyed the Japanese 51st Division. American maps identified the areas just inland from the landing areas as “damp flat.” That was optimistic at best. The place was a misery of jungle and leeches. In the words of Bernard Nalty, “…a Marine might be slogging through knee-deep mud, step into a hole, and end up, as one of them said, ‘damp up to your neck.’”

Aogiri Ridge, Suicide Creek, and Hell’s Point became well known as places of misery and ambush – of a patrol taking ten steps and disappearing into the “Green Inferno” of seemingly impenetrable jungle. So hellish was the terrain that after four months, there was real concern that the 1st Division would no longer be a viable amphibious force, unless relieved.

It was and then sent to the small island of Pavuvu, for rest and refitting.

The First Marine Division was next tasked with the invasion of island of Peleliu, in the Palau island group. The Palau campaign had originally been planned as a side show to General Douglas MacArthur’s re-taking of the Philippine Islands. The Palaus, to the east of the Philippines were to be taken in order to protect MacArthur’s right flank. Because of the speed of the Allied advances in the Southwest Pacific, serious doubts were raised as to the necessity of attacking the Palau island group at all. Arguments were made that the islands could be isolated, neutralized and by-passed. In one of the imponderables of war, the attacks were not cancelled. The First Marine Division with its three infantry and one artillery regiment was assigned to what was assumed to be a three to five day conquest of the island of Peleliu. Despite intense and protracted naval bombardment and aerial attacks, the thousands of defenders hunkered down in caves and tunnels. What was thought to be a relatively casualty-free campaign ended up as a bloody and protracted fight that decimated the Division’s First Regiment, cost the division and the US Army’s 81st Infantry Division nearly 2000 dead and total casualties of almost 10,000. The Seventh Marines spend two bloody weeks in the Umurbrogol Pocket, a mountainous lace of sinkholes, caves and tunnels. In scenes worthy of the worst of Dante’s “Inferno,” flamethrowers, artillery, and grenades made small progress in 110 degree heat against a hidden enemy. The battle for Peleliu raged from September 15th until late November of 1944. The 81st Infantry Division finished the fight, as the exhausted and depleted First Marine Division was pulled out on October 20th and sent back to the Russell Island of Pavuvu for re-fitting.

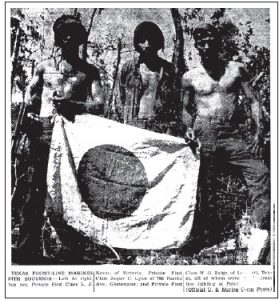

The Marine Corps photo department sent home a picture of Sonny and two other Marines holding a captured Japanese flag. It ran in the Lockhart Post Register. Sonny no longer had the look of an innocent young man. In just a few months, he had seen enough misery for several lifetimes. And the worst was yet to come.

The invasion of Okinawa in April of 1945 resulted in the bloodiest battle of the Pacific Theater. It lasted 82 days. Six divisions; four Army, and two Marine, were in the fight. Huge numbers of aircraft and naval vessels were involved. It cost the lives of 12,513 soldiers, sailors and marines, including several Caldwell County men, and the US commanding officer, General Simon Bolivar Buckner. There were over 72,000 wounded and non-combat losses for the Americans. The Japanese defenders lost over 100,000 men killed. Caught in the middle of the maelstrom, the number of Okinawan civilians killed has been estimated at well over 100,000. The ferocity of the Japanese defense of an island 350 miles from its home islands lay to rest any thought of the United States not using atomic weapons instead of attempting an invasion of the three main Japanese islands.

The invasion of Okinawa in April of 1945 resulted in the bloodiest battle of the Pacific Theater. It lasted 82 days. Six divisions; four Army, and two Marine, were in the fight. Huge numbers of aircraft and naval vessels were involved. It cost the lives of 12,513 soldiers, sailors and marines, including several Caldwell County men, and the US commanding officer, General Simon Bolivar Buckner. There were over 72,000 wounded and non-combat losses for the Americans. The Japanese defenders lost over 100,000 men killed. Caught in the middle of the maelstrom, the number of Okinawan civilians killed has been estimated at well over 100,000. The ferocity of the Japanese defense of an island 350 miles from its home islands lay to rest any thought of the United States not using atomic weapons instead of attempting an invasion of the three main Japanese islands.

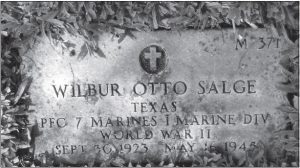

The initial landings on Okinawa were unopposed. Then came the kamikazes – suicide airplanes that sunk or damaged dozens of ships. On the ground, Americans split the island in two with relative ease. Some began to think things wouldn’t be so bad. They were soon disabused of that notion. The Japanese commander, Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, was a defensive genius, and he had the terrain to prove it. Retreating to mountains in the north and south of the island, the Japanese defenders made the Americans pay for every inch of land taken. If possible to do so, torrential rains made things even worse. Bodies lay rotting in the mud. Tanks could not move. GIs’ and marines’ clothing rotted on them, as they moved from cover to cover. In the south, the 1st Marine Division attacked a line of defenses held by deadly ridgelines. Marine Colonel Joseph Alexander noted in his history of the Okinawa campaign that after a fierce fight to seize one of the ridges, “the next 1,200 yards of [the First Division’s] advance would eat up 18 days of fighting. In this case, seizing Wana Ridge would be tough, but the most formidable obstacle would be steep, twisted Wana Draw that rambled just to the south, a deadly killing ground, surrounded by towering cliffs pocked with caves, with every possible approach strewn with mines and covered by interlocking fire.” It was in this action that on May 16, 1945, PFC Sonny Salge was killed. He was twenty years old.

Sonny’s body was eventually returned to the United States, but not to Texas. He is buried in Section M, Site 371, National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, located in the Punchbowl in Hawaii.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Sonny’s sister, Dorothy Norman—an energetic 92-years-of-age in 2013—visited with me and provided Sonny’s photo, as well as stories of her brother and his childhood in Lockhart. Tommy Holland (d. 2016) also provided some background on Sonny. Muster rolls were used to track his location after assignment to the 7th Marines. “Cape Gloucester: The Green Inferno,” by Bernard C. Nalty (www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/USMC-C-Gloucester/) gave insight into that hellhole. The picture of Sonny’s headstone was provided by Fred Weber.

It might just be the name but it strikes me to read this story while remembering my own grandfather H. “Mulle” Salge who fought the second world war on the other side and barely survived Russia. Looking at his drawings from back then makes me wish that we never have to see another war like that, that no young men and women have to fight and die. Sonny and Mulle Salge might only be connected by name but the pain stays – for both.

Thank you and Sunny’s Connections for sharing his story.

Thanks. Good insight. Both went through hell.