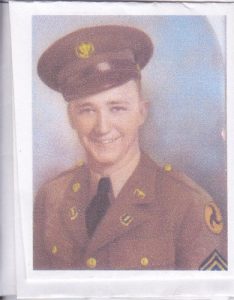

Sam Scrap Fairchild (and Scrap was his real middle name) was born on October 22, 1922. His father Mitchell Cleve (“M.C.”) was born in Fannin County, Texas in 1886. His mother, Frances Emma “Frankie” Vaughan was born in Nolan County in 1895. Both had been previously married. M.C. had two children, Robert Mitchell Fairchild and Mary Florence “Eileen” Fairchild from his first marriage. Frankie had two children, Willard and Leona McAllister, from her first marriage.

M.C. was a cattle and stockman. Prior to marrying Frankie he lived in San Elizario, El Paso County, trading horses across the border into Mexico. It was a not an occupation for the faint of heart, especially given the lawless conditions engendered by the Mexican Revolution. M.C. and Frankie married in 1920 and the Fairchild family grew quickly. Scrap was born in Big Spring, Howard County, the second of the Fairchild children. Scrap’s older brother was Monroe Stump Fairchild, and younger brothers were Lyda McGowen “Mac” Fairchild, James Mitchell “Jimmie” Fairchild, and Hoot Cleve Fairchild.

The Fairchilds arrived in the Caldwell County area by an interesting route. M.C.’s ranching business took his new family into the Big Bend country. Frankie tired quickly of the arid and treeless expanse. M.C. asked her where she wanted to move, and Frankie, looking at a sack of flour milled in Seguin picturing trees and greenery, insisted that was where she wanted to go. They family traveled by oxcart, settling first in the Darst Field area, where Scrap attended but did not complete Dowdy School.

In 1937, the family moved into Caldwell County to the Hall Cemetery area. Scrap was extremely likeable, popular with the girls, and a good dancer. His best friend was Crawford Woodrow “Doodle” Watts. In 1940 Doodle and Scrap decided they were going to join the Army and “see the world.” Scrap got M.C.’s permission to enlist at seventeen. Doodle would end up in the China-Burma-India Theater, as an aircraft mechanic.

Scrap enlisted in the Army Air Corps as a private on May 20, 1940. According to his enlistment records, he was 5’10” tall and weighing a lean 141 pounds.

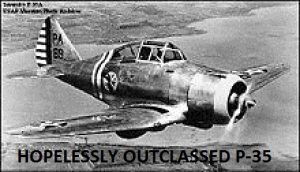

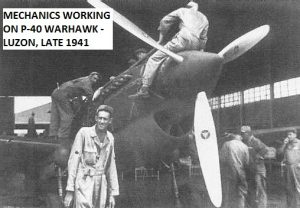

After basic training he was assigned to the 21st Pursuit Squadron as a cook. The squadron’s pilots, ground crews and aircraft sailed in blackout conditions from the United States, arriving on Luzon Island, Philippines eighteen days before the attack on Pearl Harbor. There had been little doubt that war was coming – the question was where the Japanese would attack. The 21st’s transfer was part of a belated attempt to strengthen The American Army Air Corps fighter forces. The 24th Pursuit Group’s aircraft were obsolete and obsolescent aircraft, such as the P-35 and the P-40.

Japanese air strikes, and large landing forces doomed the defenders. Hopelessly outnumbered and outclassed, American airpower was decimated almost immediately. General Douglas MacArthur’s American and Filipino defenders declared Manila an open city, and then conducted a fighting retreat into the Bataan Peninsula. The 21st Pursuit Squadron ground echelon moved from Lububo to KM Post 184 and was made into a regimental reserve for the 71st Infantry Division. What pilots remaining were attached to aircraft which were flown to Mindanao. Ground crews were out of luck. For three months the Battling Bastards of Bataan (“We’re the Battling Bastards of Bataan, No Mama, No Papa, No Uncle Sam. No aunts, no uncles, no cousins, no nieces. No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces. And nobody gives a damn!”) held out against overwhelming odds. Finally, decimated by disease and starvation, the forces surrendered on April 9, 1942.

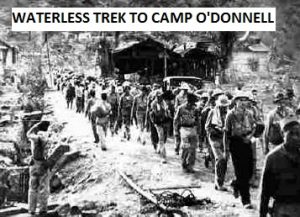

The Japanese were unprepared to handle the sheer number of captives – 12,000 Americans and 66,000 Filipinos. Surrender was anathema to the Japanese culture as well. The two realities helped create one of the War’s worst incidents – The Bataan Death March.

At least 5000 Filipinos and between 500 and 600 Americans died from bayoneting, beatings, shootings, starvation and dehydration on the 55 mile trek in 100 degree tropical heat. Arriving at the rail terminus at San Fernando, survivors were crammed into boxcars and shipped to prisoner of war camps. Most ended up at Camp O’Donnell. Malaria and dysentery were rampant. The principal diet was rice, with an occasional tablespoon of camote, a native sweet potato. Men assigned to the burial detail would often drop dead themselves. Incredibly, during the period from April 15, 1942 to July 10, 1942, 21,684 Filipinos died (an average of 249 a day) and 1488 Americans died (an average of 17 a day). The US Air Force Fact Sheet tells the grim story of the Philippine defenders’ fates:

Although it is difficult to establish exactly what happened to all the USAAF personnel on Bataan, the record of the USAAF’s 24th Pursuit Group illustrates the high price they all paid. Eighty-three of the group’s 165 pilots were captured, 33 were killed, and 49 were evacuated. Of the 83 captured, only 34 made it home after the war — 17 died in captivity and 32 more died on hell ships. Of the group’s 27 non-flying officers, one was evacuated, one was killed, and 25 became POWs (15 died in camps or on ships). The enlisted men suffered equally. Of the 1,144 men at the start of the fighting, 16 were evacuated, 38 were killed, and the remainder became POWs, of whom over 60 percent died in captivity.

Scrap survived the  Death March. He died in the hell of Camp O’Donnell on May 20, 1942. He was just nineteen years old.

Death March. He died in the hell of Camp O’Donnell on May 20, 1942. He was just nineteen years old.

In 1949, Scrap’s body was returned to Texas from the Philippines, and he is buried at Section S, Site 214 of Ft. Sam Houston National Cemetery.