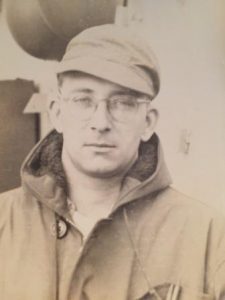

LW Mooneyham 1942 Boot Camp

LEONARD MOONEYHAM – CELEBRATING A LIFE FULL OF EXCITEMENT

BY Todd Blomerth

On February 26, 2015, Leonard Mooneyham turned 90 years old. His mind, memories, and wit are as sharp as ever, although his body is letting him down. “Mooney” is fighting cancer, his fifth go-round with the disease. He doesn’t allow it to interfere with visits from friends and family, or with a nosy judge who comes by asking him a load of questions about a most interesting life. Like with so many of his era, my biggest regret is not getting to know him sooner. Mooney is the father of three sons – Wesley Ray, Bobby, and Mark, who died of pancreatic cancer. He is also the proud step-father of Ed Theriot and Debbie Rawlinson. He married their mother Frances Faye Stanford in 1972.

Leonard was born in 1925 (that’s his story and he’s sticking to it) in Black Oak, Arkansas, the son of a lawman who became Chief of Police in Hope, Arkansas. His parents divorced and his mother, Sylvia Fischer, remarried. His step-father, Chester Warmbrodt, at one time a test pilot for Stinson Aircraft, found work in Oklahoma. The family moved to northern Oklahoma when he was young. He attended a one room school named Chimney Rock School, and then attended high school in Bartlesville, essentially a company town for Phillips Petroleum Company. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 stirred most young men’s patriotic zeal. Mooney was no exception. Quitting school, he and some friends, fudging their ages a bit, enlisted in the Navy. Gifted in mathematics and with excellent hearing, Mooney didn’t get his first choice of assignments – as a cook and baker. Instead, two weeks into basic training, he was assigned to sonar training. Sonar equipment was an absolute necessity to protect ships from submarine attacks, as its soundings allowed for underwater detection. After training, for a time he and five other young sailors were given Thompson submachine guns to stand guard as secret electronic equipment was installed on destroyers outside of San Francisco. Mooney still chuckles at what must have been a scary sight – young men, some barely shaving, lugging around fully loaded automatic weapons they were untrained on.

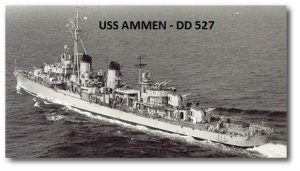

Mooney was then transferred to the USS Ammen, a Fletcher class destroyer with hull designation DD527. He remained a member of Ammen’s crew for the remainder of World War II.

Laid down in November of 1941, Ammen was commissioned in March of 1943. After a shakedown cruise, Ammen headed to the frigid waters of Alaska to take part in the Aleutian Campaign. Little understood and rarely discussed, the Aleutian Campaign was one of America’s most difficult efforts in World War II. It was a miserable place to fight a war, and Ammen, slated for the Mediterranean, did not have the cold-weather gear for her 350 man crew. Heavy seas took a toll on the 2000 ton displaced ship. “It is sixty-nine feet from the bridge to the waterline,” Mooney says. “There were many days when I saw green water [not just spray] come over the bridge!” A sailor was washed overboard – the seas were too high to attempt to effect a rescue. He was never found. Fog was often so thick sailors literally could not see more than five feet ahead of them. Ammen was part of the invasion of Attu. American soldiers and sailors suffered mightily from the foul weather. Eventually the Japanese garrison was wiped out. After screening convoys to Adak and Kiska, Ammen shepherded small craft to Pearl Harbor. During that journey, seas were so rough that often lookouts would lose sight of other ships in the troughs. Keeping the ships in close proximity required lookouts to chart their locations with grease pencils when the small vessels came up onto the crests of the huge waves. When Ammen finally arrived at Hawaii, its crew, now properly clad in cold-weather gear, nearly burned up in the tropical sun.

Ammen’s next nine months was in the Southwest Pacific. It supported landings at Cape Gloucester and provided antisubmarine and antiaircraft protection for the larger ships. It also provided suppression fire onto Japanese coastal defenses. The same went for landings on Los Negros. It participated in anti-shipping sweeps off the coast of New Guinea, and then gave protection to assaults on Tanamerah Bay and Hollandia. Biak, Bosnik, Noemfoor, Sansapor, Morotai – odd sounding places now, but in 1944 they were all part of the Americans’ advance toward the Japanese home islands. Often attached to Australian naval task forces because of the Americans’ superior radar, Ammen went out ‘in the dark of the moon’ to limit tell-tale phosphorescence in the ships’ wakes. And men took liberty in Sydney – something the American sailors loved.

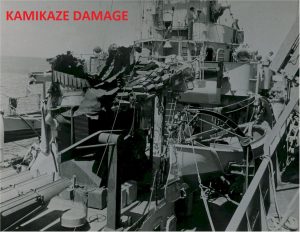

Ammen escorted ships into Leyte Gulf for Americans’ first landings on the Philippines – part of General Douglas MacArthur’s vow to re-take the islands lost in 1942. The Japanese Navy was badly mauled at Surigao Strait and San Bernardino Strait, so it began resorting to an aerial blitz. Destroyers were the ‘guard dogs’ of convoys and moored ships. With radar and visual observers they were the trip-wires, or picket ships, guarding against attacks on larger ships with their huge crews, aircraft and equipment. On November 1, 1944, Mooney was a gun director for the Ammen’s forward and port-side quad-40 mm anti-aircraft weapon. His station was just below the bridge. In one of the earliest of the kamikaze attacks, a twin-engine Yokosuka P1Y “Frances” bomber took aim at Ammen, coming straight in on her bow. On the bridge, the quartermaster spun the wheel frantically, swinging the picket ship to starboard just enough that the kamikaze missed the bridge (and Mooney) and crashed between the two stacks. Five men were killed and 21 wounded.

Ammen shot down two other aircraft while on picket duty, and on November 16, 1944 sailed back to San Francisco for repairs. Patched up, she then endured the unending onslaught of kamikazes that sunk or damaged hundreds of ships and killed nearly 5000 sailors during the horrific battle to take the island of Okinawa. Destroyers took a heavy toll protecting landing forces and larger ships. Destroyers posted on radar picket patrols were the first line of defense from incoming kamikazes. As such, Japanese bombers and suicide planes took a fearsome toll on the small ships and their crews.

One night a near-miss by a bomb showered the ship with shrapnel. Eight men were wounded. Along with her sister ship Bennion (DD-662) she was attacked and shot down several kamikazes during April and May of 1945. While the Americans tried to occasionally spell picket ships off Okinawa, the emotional and physical wear and tear on ships and men was often overwhelming. Imagine yourself a teenaged sailor on a small ship, sitting in the ocean, watching a determined suicide bomber coming straight at you, intent on killing you and your crewmates. Once the suicide planes get past air cover, your only defenses are anti-aircraft shells which often appear to have no effect.

One night a near-miss by a bomb showered the ship with shrapnel. Eight men were wounded. Along with her sister ship Bennion (DD-662) she was attacked and shot down several kamikazes during April and May of 1945. While the Americans tried to occasionally spell picket ships off Okinawa, the emotional and physical wear and tear on ships and men was often overwhelming. Imagine yourself a teenaged sailor on a small ship, sitting in the ocean, watching a determined suicide bomber coming straight at you, intent on killing you and your crewmates. Once the suicide planes get past air cover, your only defenses are anti-aircraft shells which often appear to have no effect.

Although Mooney’s principal job was that of a sonarman, he, like many other crewmen, had a secondary job when at battle stations for air attacks. Every time radar picked up incoming aircraft, his role as a sonarman became secondary to anti-aircraft stations. During the night of May 24/25 a Nakajima Ki. 44 ‘Tojo,’ aiming for Ammen, missed her but crashed into the nearby Stormes (DD-780). On May 27, 1945, Ammen and Boyd (DD-544) fought off eight coordinated air attacks. Finally, as Japan ran out of airplanes and pilots, the threat abated, and Ammen finished the war patrolling in the East China Sea.

Although Mooney’s principal job was that of a sonarman, he, like many other crewmen, had a secondary job when at battle stations for air attacks. Every time radar picked up incoming aircraft, his role as a sonarman became secondary to anti-aircraft stations. During the night of May 24/25 a Nakajima Ki. 44 ‘Tojo,’ aiming for Ammen, missed her but crashed into the nearby Stormes (DD-780). On May 27, 1945, Ammen and Boyd (DD-544) fought off eight coordinated air attacks. Finally, as Japan ran out of airplanes and pilots, the threat abated, and Ammen finished the war patrolling in the East China Sea.

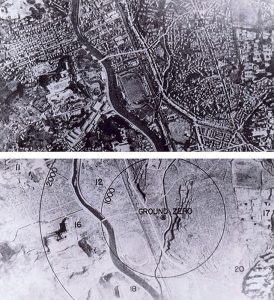

On August 6, 1945 the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. On August 9, 1945,

Nagasaki was obliterated. Finally Japan surrendered. Ammen was ordered to support efforts to recover Allied prisoners of war from the hell of POW camps. Mooring at Depima Pier at Nagasaki on August 15, 1945, its log of August 16th noted “smell from bodies noticeable.” Mooney and others were driven all over the blast zone in open trucks while assisting in the of POWs’ evacuation to hospital ships. Ammen’s crew was awestruck by the devastation. In the words of Bill Raab, speaking at an Ammen reunion in 2002, “You couldn’t imagine one bomb causing that kind of destruction. It seemed utterly out of some science fiction book. Everything was just leveled. There were people walking around in a daze, animals dead on the side of the road. You couldn’t imagine that it was a city at one time.” There was substantial ignorance as to the long-term effect of radiation. Japanese survivors would find out about cancers caused by exposure to the blast. Americans, perhaps unknowingly, placed their own men in harm’s way afterward. Photography was prohibited, and authorities confiscated all Mooney’s photographs of the desolation of Nagasaki. Mooney has fought five different cancers over the years. He attributes these to exposure to the radiation at Nagasaki.

Mooney had more than enough time overseas to be sent home immediately after the war. However he took leave one night in Japan, and a subordinate wangled a trip home for a supposed medical emergency. Mooney was declared indispensible and got stuck helping sail Ammen home through the Panama Canal to Charleston, S.C. for de-commissioning. Ammen and her crew were warriors. The ship earned eight battle stars during World War II. It participated in 19 ground invasions, destroyed eight Japanese mines, sank three enemy ships, and shot down twenty-one aircraft.

Mooney didn’t get back home to Oklahoma until April of 1946. He enrolled in the University of Oklahoma but never got his degree. Turns out that his Navy training in electronics put him well ahead in practical terms of most of his professors. He went to work for Phillips Petroleum, and began a lifetime of work in the oil and gas industry that took him all over the world.

But there was an interruption. In June of 1950, North Korea attacked the south, and was narrowly kept from overrunning the entire peninsula. After the surprise landings at Inchon, Allied forces sped north, pushing the North Koreans back toward the Chinese border. General Douglas MacArthur, in one of the worst errors every perpetrated by a military commander, split his command advancing into the mountains of North Korea, where there was no mutual support. Ignoring repeated warnings of Chinese intervention, he ordered X Corps to seize reservoirs in the mountains near the Chinese border. Made up of the Marine 1st Division and Army units, X Corps was surrounded and attacked. Although a ‘victory’ of sorts, the Chinese lost over 40% of their troops to the desperate marines and soldiers. Retreating while holding back hundreds of thousands of Chinese in an incredible display of valor, most of the American forces made it to the the port of Hungnam in North Korea, where they were desperately awaited evacuation.

Re-activated into the active Navy almost immediately after the invasion of South Korea, Mooney was shipped to Japan. Despite having destroyers in the United States kept in readiness, the Navy desperately needed ships in Asia. Several patrol frigates, much smaller than destroyers, were moored in Japan. They had been ‘loaned’ to the Soviet Union in 1945 in anticipation of its entrance into the Pacific War. Grudgingly returned from their loan to the Soviet Union in 1949, these ships were fraught with problems and skilled sonarmen were needed to help get them up and running. Mooney was assigned to USS Hoquiam (PF5). Hoquiam, after four years with Soviet navy, was, to say the least, in bad shape. Mooney and a crew worked furiously to get the 1200 ton ship operational. It was soon part of a 139 ship flotilla that sailed to Hungnam in North  Korea in early December, 1950. Historian Roy Appleman has called this “the greatest evacuation movement by sea in US military history.” 105,000 marines and soldiers, 98,000 Korean civilians, 17,500 vehicles, and 350,000 tons of equipment were taken off the Korean coast, just ahead of the advancing Chinese army. LSTs took as many of the terrified Koreans as they could. One incident Mooney witnessed was both poignant and humorous. A Korean farmer was hell-bent to get his donkey and cart onto the LST. The LST’s loadmaster had no intention of letting an animal into precious human cargo space. Thousands of desperate Koreans were being loaded. Frustrated at the impasse, the loadmaster pulled out his .45 and shot the donkey beween the eyes, then dumped the dead animal and cart into the harbor. The Korean farmer was then allowed on to make his escape.

Korea in early December, 1950. Historian Roy Appleman has called this “the greatest evacuation movement by sea in US military history.” 105,000 marines and soldiers, 98,000 Korean civilians, 17,500 vehicles, and 350,000 tons of equipment were taken off the Korean coast, just ahead of the advancing Chinese army. LSTs took as many of the terrified Koreans as they could. One incident Mooney witnessed was both poignant and humorous. A Korean farmer was hell-bent to get his donkey and cart onto the LST. The LST’s loadmaster had no intention of letting an animal into precious human cargo space. Thousands of desperate Koreans were being loaded. Frustrated at the impasse, the loadmaster pulled out his .45 and shot the donkey beween the eyes, then dumped the dead animal and cart into the harbor. The Korean farmer was then allowed on to make his escape.

Mooney’s ship had a contingency of Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs – forerunners of the Navy SEALS) tasked with destroying the port facilities once the evacuation was accomplished. Hoquiam was the last ship out of the harbor after the charges were set. It was given 45 minutes to vacate the harbor before demolition charges blew. And its engines wouldn’t start. UDT members and the crew thought Hoquiam would go up with the harbor installations. Fortunately a sea-going tug pulled the ship out of harm’s way. It was another close shave. Hoquiam was awarded five battle stars for her service during the Korean War.

After Korea he built pipelines in Alaska and Canada. His work with Phillips and Fluor and his own company took him all around the world. Mooney lived in Venezuela near the Dutch islands of Aruba, Curacao, and Bonaire. He helped build a carbon black plant in Guanajuato, Mexico. He built refineries in Spain. He built cryogenic natural gas capture installations in Borneo.

His civilian work put him in harm’s way as well. Fluor sent him to assist in a refinery retrofit in Iran, shortly before the Shah abdicated. He worked near Teheran, and then at refinery in Isfahan. After the Shah left Iran to be treated for cancer, Mooney was able to get his family out. He went back to Iran to finish the job. The Ayatollah Khomeini came to power and shortly afterward, the American Embassy staff was captured and held for 440 days. Near Fluor’s worksite at Isfahad were men from a German company building a cement plant. Somehow obtaining German passports and intermingling with the Germans, the Americans with Fluor headed to the Teheran airport. Photos on the German passports looked vaguely similar to the Americans using them. Pretending to be leaving for a short leave, the Americans, intermingled with and emulated their German counterparts, took only small carryon luggage. Mooney is proud to say that “nothing worked [at the Iranian facility being upgraded] when we left!”

Mooney’s life has been incredibly interesting and full as you can tell. He has combined an analytical mind with a can-do attitude. There isn’t much he hasn’t built or improved on through the years. He has raced BSA motorcycles, built dune buggies to race on the sanddunes of the Coro Peninsula in Venezuela, and was a licensed ham radio operator. While working in Borneo, Faye contacted him about buying a place to live in Caldwell County where two of her sisters lived. They bought much of downtown McMahan. While he continued to work overseas, Caldwell County became ‘home base.’ Finally retiring for the third and final time in 1993, Mooney settled down to enjoy life. Folks in the McMahan area afforded Mooney and his family many years of happiness and friendship. Selling his property in 2003, he and Francis moved to the Texas Gulf Coast. As he says, “The fishing was great!” Mooney lost his life-partner in 2011 and moved back to Lockhart, to be closer to some of his family.

Mooney is understandably extremely proud of his ship’s role in World War II. He is also proud of America’s efforts in World War II and Korea. He relishes his wonderful friends and family. He has had a wonderful life.