PROMISES WERE MADE AND BROKEN, ORDERS WERE MADE AND THEN DELAYED, AND HE’S THANKFUL IT TURNED OUT THAT WAY

By Todd Blomerth

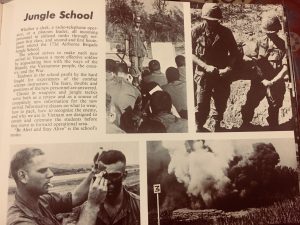

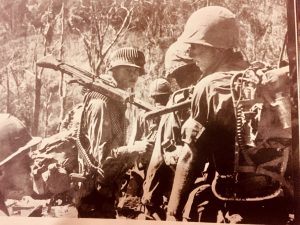

Hundreds of young soldiers sat in the hot bleachers. They were beginning the 173rd Airborne Brigade’s two week jungle school at An Khe, Vietnam. The training sergeant eyed the newly-arrived men. “Look to the man on your left,” he shouted. “Now to the man on your right. Now look to the man in front of you. Now to the back. Only one of you will come back from Vietnam just the way you got here.”

As Ken recounted this, his voice and countenance changed noticeably. The sergeant was wrong. No one who experienced combat and field operations in Vietnam returned home unchanged.

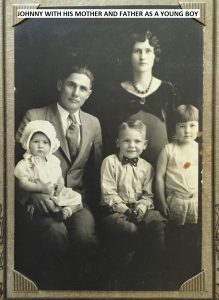

. Ken’s mother, Malou King, was a Mississippi farm girl. His father,

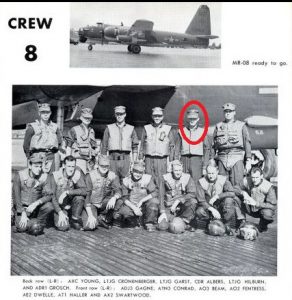

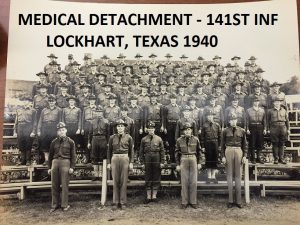

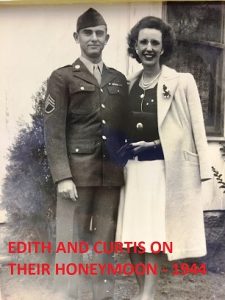

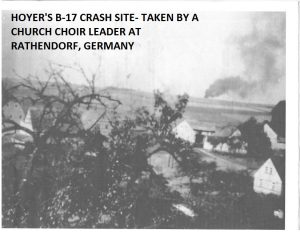

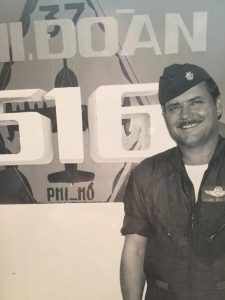

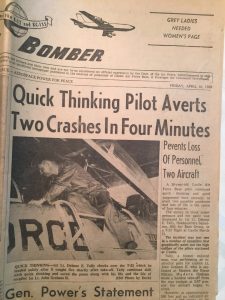

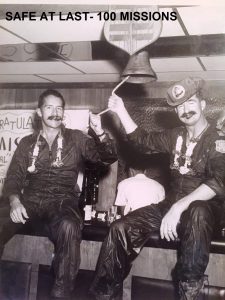

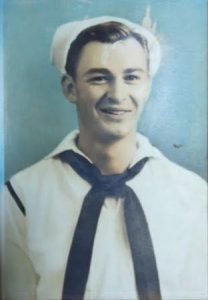

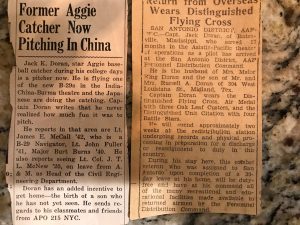

the son of a West Texas sheep rancher, was a Fightin’ Texas Aggie, Class of 1940. The two met in Little Rock, Arkansas. Jack Kennedy Doran, Sr. flew B-29 Superfortress bombers out of India and later the Pacific during World War II and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. His family is quite rightly proud of his service to his country. After the war, he joined his family’s farming operation in Midland, TX and also contracted as a civil engineer with various companies in West Texas. Jack Kennedy “Ken” Doran, Jr. was born in Midland, Texas on April 4, 1947. Ken and his older brother Russell went to school in Midland, San Antonio and Houston, settling in Corsicana, Texas where Jack Sr. owned a Phillips 66 distributorship.

the son of a West Texas sheep rancher, was a Fightin’ Texas Aggie, Class of 1940. The two met in Little Rock, Arkansas. Jack Kennedy Doran, Sr. flew B-29 Superfortress bombers out of India and later the Pacific during World War II and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. His family is quite rightly proud of his service to his country. After the war, he joined his family’s farming operation in Midland, TX and also contracted as a civil engineer with various companies in West Texas. Jack Kennedy “Ken” Doran, Jr. was born in Midland, Texas on April 4, 1947. Ken and his older brother Russell went to school in Midland, San Antonio and Houston, settling in Corsicana, Texas where Jack Sr. owned a Phillips 66 distributorship.

Corsicana was by Ken’s account, a great place to grow into adulthood. He lettered in basketball and enrolled at Texas A&M in the fall of 1965.

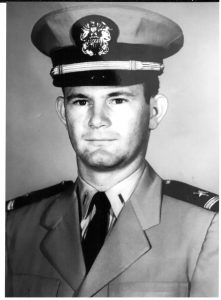

fish Doran – A&M – 1965

Studying didn’t agree with Ken. With dreadful grades, “I was invited not to come back,” he told me jokingly. He made another stab at it, taking courses at Navarro County Junior College, but clearly, Ken wasn’t ready yet to finish his college education.

Ready or not, the Army was ready for him.

It’s hard to explain the choices, or lack thereof, available to draft-age men in the late 1960s. The United States was embroiled in a seemingly never-ending war in Southeast Asia. Enlistment or being drafted into the military often resulted in a tour of duty in the war zone of Vietnam.

Ken was, and is, a very patriotic American, Young and seemingly invincible, he wanted to help his country in its war. Not only that, he wanted to do it as a helicopter pilot – an incredibly dangerous occupation with a very high casualty rate.

To speed the process along, he reckoned that if he had to serve, he’d enlist rather than wait to be drafted. Off he went to “Tigerland,” Fort Polk, Louisiana. It was common knowledge that, if you scored well on your initial testing, and if you were in excellent physical shape, you could apply for Officer Candidate School, and Army Flight School, while you were taking Infantry Basic Training and Advanced Infantry Training (AIT). Ken was a fit in both categories.

Here, the Army threw its first monkey wrench into his plans. While in basic, a young 2nd lieutenant told Ken, “You can’t go to OCS. You don’t have a college degree.” The shavetail was totally wrong. Being a new recruit, Ken didn’t know it, and opted for another route toward his dream of flying helicopters. Scurrying around amid the time constraints of basic training, Ken somehow managed to complete his application and physical for Flight School. Successful completion of that school meant a commission as a Warrant Officer, a single-track specialty officer, and getting to fly. Things were looking up. Surely, upon completion of AIT, he’d be on his way to the Army’s helicopter flight school at Fort Wolters, Texas.

Instead, Ken wound up at Airborne School at Fort Benning, Georgia. Three ‘fun’ weeks went by; he earned his jump wings, but still no orders. Where were they?

Army Special Forces are an elite fighting force. Figuring the Army had ignored his request for flight school, Ken had the opportunity to go to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and vie for the coveted Green Beret. However, he and his girlfriend at the time were supposed to be in a wedding back in Corsicana. “If I sign up for Special Forces training, will I get any time off?” “Oh no,” said an instructor. “The class starts immediately.” Ken decided against signing up for the Special Forces’ program. After jump school, he went home to be in the wedding, and later received an infamous “Dear John” letter. In Vietnam, he ran into someone who had volunteered for Special Forces training. “Turns out,” Ken told me, “the guys got to Fort Bragg, and were given thirty days leave, as there were no classes starting at that time!” The Army had thrown him another curve ball.

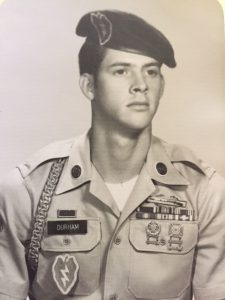

Still waiting for the elusive orders for flight school, he received his next set of orders. He was assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade. PFC Ken Doran was going to Vietnam. As an airborne infantryman.

Pfc Doran and hundreds of young men flew from McCord Air Force Base, through Anchorage and Japan. As the jet banked toward a landing at Cam Ranh Bay, he thought to himself, “What have I gotten into?”

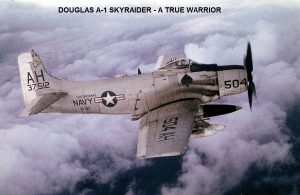

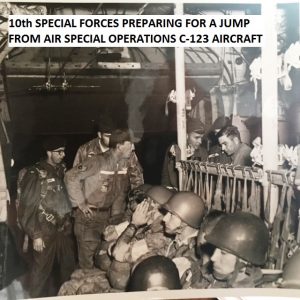

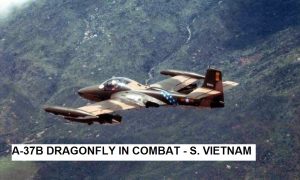

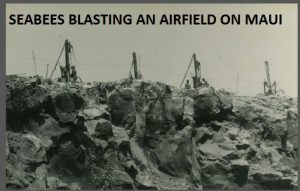

In-country, the men were processed, given one week of acclimatization and ‘culture school.’ He loaded onto a C-123 transport that took him to An Khe. The aircraft landed at an old “shot-up” French airfield. Then two weeks of jungle school began. “We learned how to use claymore mines and improvised explosives. We learned how to make and detect booby traps, and call in air strikes. If necessary, a Pfc could even call in a B-52 strike.”

In-country, the men were processed, given one week of acclimatization and ‘culture school.’ He loaded onto a C-123 transport that took him to An Khe. The aircraft landed at an old “shot-up” French airfield. Then two weeks of jungle school began. “We learned how to use claymore mines and improvised explosives. We learned how to make and detect booby traps, and call in air strikes. If necessary, a Pfc could even call in a B-52 strike.”

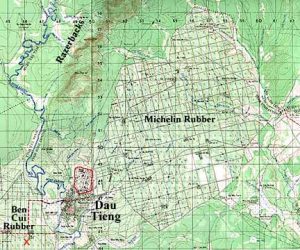

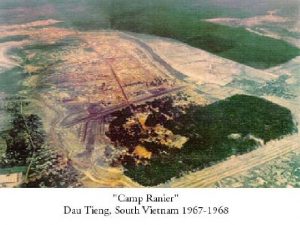

Ken’s arrival with the unit was fortuitous. The North Vietnamese Tet  offensive of January 1968 had been a bloody tactical disaster for the NVA and VC. However, it had proved a propaganda success with the American public. Shocked at the growing number of American deaths (there would be over 14,000 in 1968), President Lyndon Johnson replaced his military leadership in Vietnam, refused to substantially increase the number of American troops, and told the South Vietnam leaders they needed to start carrying a heavier load in the war. The 173rd was a proud outfit that has seen several nasty battles in 1967 and early 1968. It had badly mauled the enemy, but in the process had taken substantial casualties. Hill 882, Dak To, and Hill 875 became synonymous with death and destruction. Its combat effectiveness reduced, the 173rd was re-located to a ‘quieter’ zone of combat just before Ken’s arrival.

offensive of January 1968 had been a bloody tactical disaster for the NVA and VC. However, it had proved a propaganda success with the American public. Shocked at the growing number of American deaths (there would be over 14,000 in 1968), President Lyndon Johnson replaced his military leadership in Vietnam, refused to substantially increase the number of American troops, and told the South Vietnam leaders they needed to start carrying a heavier load in the war. The 173rd was a proud outfit that has seen several nasty battles in 1967 and early 1968. It had badly mauled the enemy, but in the process had taken substantial casualties. Hill 882, Dak To, and Hill 875 became synonymous with death and destruction. Its combat effectiveness reduced, the 173rd was re-located to a ‘quieter’ zone of combat just before Ken’s arrival.

However, in March 1968 when he arrived, “everyone was still jumpy from Tet,” Ken recalled. He was sent to a combat battalion at Bong Son in Binh Dinh Province. Three weeks of operations ensued, including avoiding an ambush that had troops scurrying to avoid incoming mortar fire. Then suddenly, one set of orders caught up with him. A sergeant told him, “You’ve got orders to report back to headquarters at An Khe. You weren’t supposed to be here.” Combat infantryman Doran found out he’d been assigned as a pay clerk.

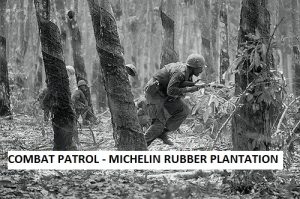

This was a great opportunity to avoid combat zones, stay safe, and ride out the remaining eleven months in-country. Ken chose a different route. The finance officer sought out volunteers to take Military Pay Currency (MPC, or ‘scrip’) to the soldiers at outposts. Loading up ‘monopoly money’ in plastic bags which were stuffed in rucksacks and fatigue pants pockets, he’d head to the airfield, catch a flight on a chopper or Caribou to fire bases. “You were a celebrity when you showed up with money,” he laughed. Sitting on an ammo crate, Ken would disburse MPC to troopers.

Often, it wasn’t that simple. Ken would arrive ready to pay troops, only to find they were loading on choppers for combat operations. “I wasn’t supposed to be there,” he recalls, “but I’d go with them so they’d get their money. Then I’d start looking for a ride back to headquarters.” I asked Ken why he took the chances. He thought about it a moment and said, “I felt obligated. In a way I felt I was supposed to be out there with those guys to begin with.” His insistence on taking care of his fellow soldiers, and repeated travels to outposts and firebases earned Ken a Bronze Star

The time in Vietnam wasn’t all life-and-death. He was able to take an R&R to Australia, and somehow, wrangle time off at Christmas to visit his older brother Russell, who was stationed at Okinawa with the Air Force. He still marvels at the “loosey goosey” way he was able to hop rides on helicopters and transport aircraft flying around the country virtually unaccounted for.

Remember Ken’s orders for flight school? They caught up with him shortly after he arrived in Vietnam. Once again, someone threw a monkey wrench into the gears. “You have to finish your one year tour before you can go back to the States for helicopter school.” Turns out, the sergeant that told him that was wrong also. Shortly before Ken’s tour ended someone finally got it right. “You don’t need to serve out your tour here,” said a noncom who knew what he was talking about. “I’ll get your orders cut right now and get you sent back.” Ken passed on the chance. It was time to go home.

Spec 5 Doran finished his military service at Fort Hood, Texas as a finance clerk with the 2nd Armored Division and discharged on June 19, 1970. He turned down $9000 in re-up bonus money, and re-enrolled in college. Ken Doran graduated from Texas A&M in 1972.

Thankfully, things haven’t been quite as exciting since he finished his military service. They have been very fulfilling, however. He met a beautiful U.T. student visiting her mother in Corsicana. He and Gail McElwrath married on December 29, 1970. They are the proud parents of three exceptional sons. Alex, older by five minutes than twin brother Jack Kennedy III (“Tres”), is an FBI agent. Tres is a CPA with KPMG. Major Casey Doran is a helicopter pilot and flew Marine One during President Obama’s terms of office. Casey also served two tours of duty in Iraq.

Ken went into banking, working at various levels within the Farm Credit System, first with a Production Credit Association in Mexia, Texas, and then with Farm Credit Administration in Washington D.C, the Farm Credit Banks in Wichita,

Kansas and finally with Texas Ag Finance in Robstown, Texas.. He earned a Masters degree in agricultural banking from Texas A&M in 1975. He and Gail came to Lockhart in 2004, when he accepted the position of branch president of American National (later Sage) Bank. He also operated the Lockhart branch of Camino Real Bank for three years, then ‘retired’ briefly. He was coaxed out of retirement, resuming his role as branch president at Sage National Bank, retiring for good in 2014.

While living in the Corpus Christi area, Ken served on the Calallen ISD school board. His encounters with a demanding coach in Corsicana gave him a strong sense of empathy for students. “We only have one shot at these kids,” he told me. “Kids can be at the mercy of those in power. We have to make sure they are given every opportunity to excel.”

Ken Doran’s life has hardly come to a halt. He and Gail have nine grandchildren and are quite active in their lives. The couple is heavily involved in the community of First Lockhart Baptist Church. Ken attended men’s Bible studies with the non-denominational Bible Study Fellowship for several years, and continues with his study of the Bible with a men’s group that meets at Emmanuel Episcopal Church on Monday nights. Ken is on the Lockhart Kiwanis Club’s ramp building team, which undertakes at least one project a month. He also a co-organizer of the Gig ‘Em – Hook ‘Em golf tournament. This annual event earns substantial scholarships for Caldwell County students attending A&M and UT.

A few more things: Ken’s got a wicked sense of humor, a keen wit, and wisdom that many of his compadres are envious of.

Lockhart is blessed to have him and Gail in our community.

BTW, Ken chose not to elaborate on the night, while on guard duty and taking sporadic VC fire, he shot out the main communication wire around one sector of the An Khe perimeter.