BY TODD BLOMERTH

I have had the privilege of knowing J. Frederic Bell since I

came to Caldwell County in 1981. He will turn 86 on March 4, but carries himself as a man much younger. His youth spent breaking horses, plowing fields, and ranching has served him well. He still insists that he can carry the load of a man half his age. If you watch him building ramps for the disabled with the Lockhart Kiwanis Club, his determination and toughness leave little doubt that he is right.

Fred came into this world in North Dakota in 1931. It was one of the toughest of times – the northern plains were in the midst of unremitting drought and the Depression. He was the fifth child, and third son of John L. Bell and Thelma German Bell. John Bell was a sodbuster. Thelma, of a ranching family, taught school in a one room school. John met Thelma, the schoolteacher, when she boarded at John’s brother’s home. They were eleven years apart. John and Thelma farmed and ranched in Stark County, seventeen miles from Belfield, the nearest settlement. They were far from electrical lines, paved roads, running water, and – until ranchers provided poles for lines in 1934 – telephones.

Thelma’s first child was born in 1924 with cyanotic heart disease, referred to then as a ‘blue baby.’ He died shortly after birth. The country doctor told Thelma not to have any more children – they would all turn out the same. She proved him wrong. Between 1926 and 1945, she and John were the parents of fifteen more children, including four sets of twins. After a sister and twin brothers, Fred was delivered at home by his paternal grandmother.

Stark County’s population was Scotch-Irish, Russian German, and Norwegian. They were tough. They had to be, as ranch and farm life in the Dakotas was unforgiving. Winters were long, and often vicious. The Bell farmhouse was near a cottonwood tree. It was the only living thing higher than row crops and prairie grass as far as the eye could see. John Bell had homesteaded 160 acres in 1913. As Fred recalls, money was ‘’invisible,” cementing John’s belief in land as a valuable commodity. Farm prices plummeted in the 20s, and by hard work, savvy business acumen, and much good fortune, by 1943 had accumulated seven sections (4480 acres) of land.

Cattle in western North Dakota were a mix of longhorns, Herefords, shorthorns, and Angus. By the time he was old enough for long pants, Fred’s job at the area roundups was tending the branding fire, and handing cowboys the iron, wrapped in a wet gunny sack, that corresponded to the right rancher as the calves were branded. By ten, he was breaking horses.

The one-room school in Stark County went to the eighth grade. Fred’s older sister took high school courses by correspondence. Fred and his twin older brothers heard the same courses being taught six or seven times in that tiny school, and essentially skipped a grade. By the age of twelve, Fred had earned the state’s eight grade certificate. John Bell wanted a better chance at education for his family. In 1943, the seven sections were sold, and the family moved to Dickey County, on the other side of the state. The family continued to farm and ranch, but John and Thelma also bought a home in town.

Ellendale, the county seat, was home to a tiny teachers’ college – North Dakota State Normal and Industrial School. The college also provided high school courses. The college enrollment was tiny, and at fourteen, he was recruited to fill out the college football squad. “But I’m fourteen,” the tenth grader told the coach. “No, you are sixteen,” the coach replied. In the middle of the war, football conferences and of-age players had disappeared. The small team traveled to nearby colleges in two station wagons.

At thirteen, Fred witnessed Dick, his beloved older brother, die when the John Deere tractor Dick was driving flipped over on him. “As I walked the half-mile to the house to tell my mother, I knew I had to assume a bigger leadership role.” And he did.

John Bell bought a lumber supply business in Ellendale in 1947, the year Fred graduated from high school. Fred received a Bachelor of Science degree in 1951 from the small college. He then enrolled at the University of Wyoming. While working on a Master’s degree, Fred met an Air Force recruiter. The Air Force was expanding its electronic warfare program. It sounded interesting, so he signed up. He was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant in 1952. While stationed at Ellington Air Force Base, outside of Houston, he met his future wife, Florence “Flo” Helen Van Dyke at a jazz jam session. They will celebrate sixty-four years of marriage on September 19th. They have four living children, seven grandchildren, and three great grandchildren.

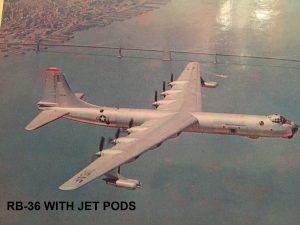

Fred’s Air Force career led him and his growing family to several assignments. He spent five years with a reconnaissance squadron at Ellsworth AFB near Rapid City. Its B-36 “Peacemaker,” was the world’s largest mass produced piston aircraft. The plane was huge, and could carry ten times the bomb-load of a B-17. The Cold War was raging, and the aircraft was one of the Strategic Air Command’s (SAC) responses to fears of a war with the Soviet Union. Many carried nuclear weapons. Others, as in Fred’s squadron, flew reconnaissance missions. With a range of nearly 10,000 miles, and a service ceiling of 50,000 feet, the recon aircraft could and often did probe (and penetrate) Soviet borders. The B-36s, with their fifteen to twenty-three man crews were placed in the far northern states for Arctic overflights. The B-36 was too slow, too complicated, and too expensive to maintain, and was soon obsolete. SAC transitioned to the jet powered B-52, which is still flying today.

at Ellsworth AFB near Rapid City. Its B-36 “Peacemaker,” was the world’s largest mass produced piston aircraft. The plane was huge, and could carry ten times the bomb-load of a B-17. The Cold War was raging, and the aircraft was one of the Strategic Air Command’s (SAC) responses to fears of a war with the Soviet Union. Many carried nuclear weapons. Others, as in Fred’s squadron, flew reconnaissance missions. With a range of nearly 10,000 miles, and a service ceiling of 50,000 feet, the recon aircraft could and often did probe (and penetrate) Soviet borders. The B-36s, with their fifteen to twenty-three man crews were placed in the far northern states for Arctic overflights. The B-36 was too slow, too complicated, and too expensive to maintain, and was soon obsolete. SAC transitioned to the jet powered B-52, which is still flying today.

Fred’s next assignment was with a combat evaluation group at Barksdale AFB, near Bossier City, Louisiana. Then it was back north, to Grand Forks AFB, where Fred flew as an electronics warfare officer on the B-52H and logged over 2000 hours. There was a brief stint at Command and Staff College in Alabama. Stability for the Bell family seemed at hand, as he was recently promoted to a major and given a staff position at Seymour Johnson AFB in Goldsboro, NC. Fred and Flo bought a house, and settled the family into what was hoped to be a long assignment. The military had other plans.

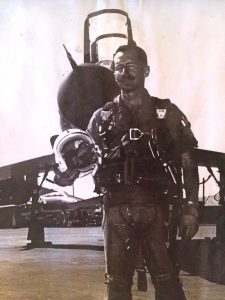

By 1965 the American commitment in Southeast Asia had grown from anti-insurgency aid to South Vietnam, into a full born war. Fifteen months after arriving at Seymour Johnson AFB, Major Bell received his new orders – he was assigned as an electronic warfare officer on an F-105 “Wild Weasel”. With a short training stop at Nellis AFB, Nevada, he was soon bound for Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base in northeast Thailand and assigned to the 13th Tactical Fighter Squadron “Panther Pack.” The eight months there would prove the most dangerous and deadly period in his life.

As the Vietnam Conflict grew into what many thought was a test of the United States’ theory of ‘containment’ of communism, the Soviet Union and communist China poured more and more resources into communist North Vietnam. The supplies flowed south, nourishing warfare in South Vietnam. There is no possible way in this biography, to discuss the efficacy of US strategy in Southeast Asia, nor try to address all nuances of the politics of the era. Suffice it to say, from a tactical point of view, US planners viewed choking off supplies to the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and insurgent Viet Cong (VC), as an absolute necessity to maintaining South Vietnam as a separate country. There would later be a sense of the futility of the effort, given country borders that existed only on paper, jungles, and the full-scale commitment of North Vietnam and its allies to achieve conquest, as well as the many moral and political questions of the US’s role in the area.

During his first years in the Air Force, Fred had taken civilian flying lessons and received his pilot’s license. The license did not endow him with the skill needed to fly a jet, but the rudiments of flying proved invaluable in the days to come.

Fred’s arrival in Thailand coincided with increasing American commitment to stopping the North Vietnamese from conquering the south. Air operations became larger and more complex.

The overall air campaign above the Demilitarized Zone was dubbed Operation Rolling Thunder. It was conceived as a way to hammer North Vietnam into submission. Political considerations devolved, some would say, into a ‘gradualism’ approach toward air warfare. North Vietnam’s capital, Hanoi, was off limits during 1965-1968, as were certain port facilities. American air power was countered by Russian and Chinese anti-aircraft artillery, and increasingly sophisticated surface to air missiles (SAMs). In 1965, the “wild weasel” concept came into being, with USAF F-100 Super Sabres playing “flashlight tag” with NVA radar and SAM sites. The plan was for Wild Weasel aircraft to lead bombing missions, and bait the NVA into turning on attack radar, and, using radar-seeking missiles, take them out before harm could come to the follow-on bombers.

F-100s weren’t up to the task, taking large casualties in a very short time. Fred says about that period, “We learned by getting shot down.” The task was then assigned to a two-seater variant of the F-105 Thunderchief, or “Thud.” Typically, four Wild Weasels would fly ahead of a bombing mission of other F-105s, with F4 Phantoms flying top cover. Hopefully, SAM and radar sites would illuminate, and the Wild Weasel aircraft could take them out with missiles before harm came to the bombing formation. Sometimes it worked.  Sometimes it didn’t. As the electronic warfare officer, Fred was the ‘backseater” on the F-105, watching a radar screen, detecting radar and SAM launch F-105 with full combat load over North Vietnam tones, listening to radio communications, and giving instructions to his pilot and three other Wild Weasels in his flight. He was fortunate to be teamed up with Major Howard “HK” White. The two became a fearsome duo. White was an excellent pilot. Fred knew his electronic counter-measures. He also knew enough about aircraft systems that he could assist as a pilot backup when needed. In Wild Weasel missions, attacks on military installations meant coming in very fast, and often very low. Two sets of eyes were crucial to survival. This was especially true as the NVA became familiar with the bombing routes. “Route Pack Six” was the main flight route from Thailand into the Hanoi/Haiphong area. “We were as predictable as the sun rising in the east,” said Fred.

Sometimes it didn’t. As the electronic warfare officer, Fred was the ‘backseater” on the F-105, watching a radar screen, detecting radar and SAM launch F-105 with full combat load over North Vietnam tones, listening to radio communications, and giving instructions to his pilot and three other Wild Weasels in his flight. He was fortunate to be teamed up with Major Howard “HK” White. The two became a fearsome duo. White was an excellent pilot. Fred knew his electronic counter-measures. He also knew enough about aircraft systems that he could assist as a pilot backup when needed. In Wild Weasel missions, attacks on military installations meant coming in very fast, and often very low. Two sets of eyes were crucial to survival. This was especially true as the NVA became familiar with the bombing routes. “Route Pack Six” was the main flight route from Thailand into the Hanoi/Haiphong area. “We were as predictable as the sun rising in the east,” said Fred.

The Americans’ predictability allowed the enemy to plant his 37mm, 57mm and 85 mm anti-aircraft batteries along known air routes. SAM missiles became more sophisticated. The North Vietnamese fighters, often flown by Chinese, also exacted a toll. Using heat seeking missiles, they would follow a fighter-bomber down, and at the vulnerable point of weapon release, shoot a heat-seeker, and then leave. The only way to avoid these missiles was by violent evasive tactics.

It was a high stakes cat and mouse game. Success for the Americans was a combat mission with no lost planes or pilots. Success for the North was disrupted bomb runs and destroyed aircraft. Both sides grew smarter the longer they dueled. USAF attacks required refueling, both inbound, and outbound. The Wild Weasel’s motto was “First In – Last Out.” Providing protection for bombing missions meant lingering over planned targets. It also meant very low fuel reserves on the return to friendly territory. KC-135 tanker aircraft weren’t supposed to enter North Vietnamese airspace. But, when necessary, they did.

Route Pack Six was considered the most dangerous airspace in the world. It covered both Hanoi and Haiphong, and therefore covered the vast majority of strategic targets in the country. As noted by one commentator:

When the air war started, the entire North Vietnamese air defense system contained twenty-two early warning radars, four fire-control radars, and 700 anti-aircraft guns. By 1967, North Vietnam was firing 25,000 tons of anti-aircraft ammunition a month. When President Johnson halted Rolling Thunder on 1 November 1968, this had grown to 400 radar sites, 8,050 anti-aircraft guns, 150 fighters (including reserves based in China), and 40 SA-2 Guideline missile sites.

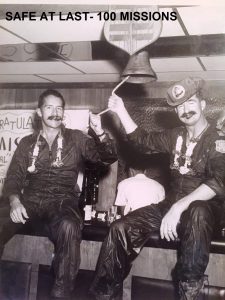

You got to got home after 100 missions, or one year – whichever came first. Fred arrived in Thailand on December 1, 1966. His first mission was on December 7, 1966. He flew his one hundredth mission on July 4, 1967. At the beginning of his tour, when there was a shortage of electronic warfare officers and Wild Weasel pilots, he flew sixty combat missions in forty-seven days.

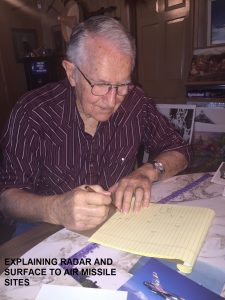

Route Pack Six fighters entered North Vietnam over the Red River. To cover their approach, Wild Weasels would often use the radar-blocking range of mountains dubbed “Thud Ridge.” Popping up, they would then begin suppression missions. If a missile took out a radar or SAM site, the Wild Weasels would follow up with low level cluster bombs. Fred received a Silver Star for his actions in one Wild Weasel action. That day, three radar sites painted the four aircraft formation. There was a launch of two SAMs from one launch site. Then a launch from another site of two more. Then a launch from a third site of two more. “You couldn’t outrun a SAM,” he said. “But it would go 2000 miles an hour. We flew at around 600 miles an hour. We had a smaller turning radius. If you knew what you were doing, you could outsmart one.” As the EW officer, Major Bell gave instructions to the four Wild Weasel F-105s which allowed them to evade the deadly missiles. As Fred says, “It was a good day.”

That day, three radar sites painted the four aircraft formation. There was a launch of two SAMs from one launch site. Then a launch from another site of two more. Then a launch from a third site of two more. “You couldn’t outrun a SAM,” he said. “But it would go 2000 miles an hour. We flew at around 600 miles an hour. We had a smaller turning radius. If you knew what you were doing, you could outsmart one.” As the EW officer, Major Bell gave instructions to the four Wild Weasel F-105s which allowed them to evade the deadly missiles. As Fred says, “It was a good day.”

There were other “good days.” Once, he spotted a new airfield being constructed enroute to another target. When the powers that be finally allowed it, the Thuds came in at low level, destroying the field with its aircraft and supporting structures. Another time, there was a confirmed destruction of a SAM battery.

Often, upon exiting North Vietnam, Fred would see smaller caliber anti-aircraft bursts just below the F105’s flight levels. “The flak bursts were as dense as any picture I’ve seen of World War II missions over Germany,” he says.

Fred makes light of the dangers he and his compatriots faced. Ed Rasimus, who flew the F-105D, wrote a memoir called When Thunder Rolled. He writes:

Over six months that it took to fly my 100 missions my roommate kept a diary that listed each time we lost someone. During the tour we lost 110% of the aircraft assigned and 60% of the pilots who started the 100 mission tour didn’t finish.

Fred’s one-hundredth mission was a rare night one. “We arrived back at two a.m. Our fellow pilots and crews kept the officer’s club open for us,” he tells me. After the ritual dunking in the officers club pool, he and White rang the 100 mission bell. They were going home.

Fred’s next assignments were interesting and far safer. While at Strike Command, he traveled to Liberia, Congo, and Ethiopia, inspecting American supported missions there. He commanded an electronic warfare training squadron. He finished his military career as an Air Force liaison officer to the Nationalist Chinese on Taiwan.

Retirement eventually brought the Bell family to Caldwell County. Fred was executive manager for the Plum Creek Conservation District for thirty years.

Never afraid of hard work, Fred has donated thousands of hours to his church and community. He has served in many capacities with the Kiwanis Club, both locally and regionally. He directed and acted in Lockhart Community Theater plays for over twenty-six years.

If you are lucky enough to catch him, thank him for his service to our country.