SAMUEL G. SERRATO

by Todd Blomerth

Soledad Garcia, at the age of fourteen, crossed into the United States on February 14, 1914 at Eagle Pass, Texas. Undoubtedly, she and her family were one of many fleeing the uncertainty and barbarity of the Mexican Revolution. She eventually married David R. Serrato who was born in Mendoza, Texas in 1900. David and Soledad lived in Maxwell, Texas for a part of their lives, where David worked for local farmers. At some point the Serratos moved with their family to 716 E. Live Oak, in Lockhart. Samuel was born on February 16, 1924, the third of seven children. His siblings included Abraham, Beatrice (Soto), Estella (Alfanador), Lucy, Rudy, and David (“Big Dave”).

Soledad and David Sr. also raised Genaro Ybarra, who they treated as a son. The Serrato family were members of St. Mary’s Catholic Church.

Samuel had some elementary school education, possibly at Navarro School. He was working as a Western Union messenger prior to entering the Army on March 11, 1943.

Samuel was one of hundreds of thousands of Americans of Hispanic descent who served in the armed forces during World War II. We know that approximately 53,000 Puerto Ricans served. Because Hispanics were not segregated like African Americans, and with the exception of Puerto Ricans, no good figures exist as to their true numbers, although estimates range from 250,000 to 500,000. Many National Guard units from the Southwest (including many companies with the 36th “Texas” Infantry Division) consisted largely of Mexican Americans.

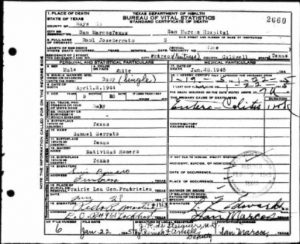

Samuel was married to Natividad Romero Garcia. Their only child, Raul Jose Serrato was born on April 2, 1944, but died on January 22, 1945 in the San Marcos Hospital with what was diagnosed as entero-colitis. Samuel would outlive his only child by less than three weeks. In all probability, Samuel never saw his son, as he was overseas in the Pacific when the Raul Jose was born.

After basic and advanced infantry training, Samuel was assigned to Company I, 129th Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Division. The division, originally a National Guard entity, saw combat in the Pacific Theater. Although his regiment was part of the 37th Infantry Division, in at least two different actions it was detached and assigned to the 33rd Infantry Division and the 40th Infantry Division. Samuel received his baptism of fire in the Bougainville Campaign. The 37th Infantry Division landed on Bougainville Island on November 13, 1943 along with the 3rd Marine Division. Bougainville is a huge island, and there was no intention of trying to drive the estimated 25,000 Japanese troops off it. Instead, the Americans established a large beachhead at Princess Augusta Bay, building airfields and supply points inside it. With its anchorage and air facilities, protection could be provided for forces used in the

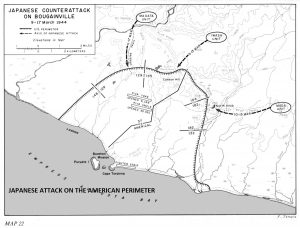

After basic and advanced infantry training, Samuel was assigned to Company I, 129th Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Division. The division, originally a National Guard entity, saw combat in the Pacific Theater. Although his regiment was part of the 37th Infantry Division, in at least two different actions it was detached and assigned to the 33rd Infantry Division and the 40th Infantry Division. Samuel received his baptism of fire in the Bougainville Campaign. The 37th Infantry Division landed on Bougainville Island on November 13, 1943 along with the 3rd Marine Division. Bougainville is a huge island, and there was no intention of trying to drive the estimated 25,000 Japanese troops off it. Instead, the Americans established a large beachhead at Princess Augusta Bay, building airfields and supply points inside it. With its anchorage and air facilities, protection could be provided for forces used in the  retaking of the Philippines. Once the Japanese defenders realized that the Americans would not try to seek them out in the island’s trackless jungles, they were forced to attack the American perimeter. After a series of small clashes, the Japanese hit the American perimeter in a series of battles in and around what became known as Hill 700 and Koromokina River between March 8 and March 23, 1944. Although the Japanese were repulsed with horrific losses, the 37th Infantry Division suffered greatly as well. The November 9, 1944 edition of the Lockhart Post Register proudly announced that Samuel received his Combat Infantryman’s Bad

retaking of the Philippines. Once the Japanese defenders realized that the Americans would not try to seek them out in the island’s trackless jungles, they were forced to attack the American perimeter. After a series of small clashes, the Japanese hit the American perimeter in a series of battles in and around what became known as Hill 700 and Koromokina River between March 8 and March 23, 1944. Although the Japanese were repulsed with horrific losses, the 37th Infantry Division suffered greatly as well. The November 9, 1944 edition of the Lockhart Post Register proudly announced that Samuel received his Combat Infantryman’s Bad![]() ge for combat on the island of Bougainville.

ge for combat on the island of Bougainville.

After the repulse of the Japanese, the 37th Division was pulled out of the line and began training for a landing on the Philippine island of Luzon. The American re-conquest of Luzon began with largely un-opposed landings at Lingayen Gulf on January 9, 1945. The U.S. Sixth Army swept down toward the capital of Manila with 175,000 men. A second landing of troops, both airborne and amphibious, moved toward the capital city from the southwest. The overall Japanese Army commander, General Yamashita, did not want to contest the city, and ordered the military there to leave the city open. Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi and his naval forces ignored the order. A bloodbath ensured. Literally thousands of innocent Filipinos were slaughtered by the enraged Japanese. Some Japanese accounts refer to it as gyakusatsu, or massacre. The atrocities beggar the imagination. Rape, murder, torture, and destruction of an entire city occurred because of the refusal to acknowledge the inevitable defeat, and the hatred for another race. Noted historian William Manchester, in his seminal book on General Douglas MacArthur writes that “[h]ospitals were set on fire after their patients were strapped to their beds. The corpses of males were mutilated, females of all ages were raped before they were slain, and babies’ eyeballs were gouged out and smeared on walls like jelly.” It is a fact to this day not acknowledged in Japan.

Those not outright murdered were often killed by American artillery and air strikes. There were an estimated 100,000 civilian deaths.

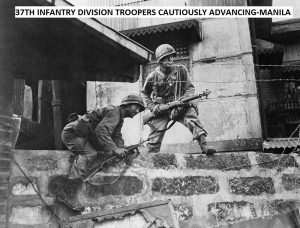

In securing Manila, the only urban fighting in the Pacific, 80% of the city was destroyed by artillery and naval gunfire. By all accounts, the battle was horrific, rivaling some of the fighting seen between Germans and Russians on the Eastern Front. It was also a cautionary tale of what could be expected fighting in built up areas. The Japanese naval forces were largely untrained in this type of fighting, had no artillery or armor, and no reinforcements. Yet they were disciplined and intent on making the Americans pay for every inch taken. Every block was fortified, and hand to hand, room to room fighting went on for weeks. Despite being vastly outnumbered, defenders held the advantage.

The 129th Infantry Regiment freed 1,330 U.S. and Allied prisoner of war and civilian internees from the Old Bilibid Prison on February 4, then crossed the Pasig River despite its destroyed bridges on February 8, and attacked Provisor Island, where the city’s electrical generation plant was located. In the words of Thomas Huber, “The 129th Infantry Regiment approached the island in engineer assault boats, then conducted a cat and mouse struggle with Japanese for control of the buildings, fighting with machine guns and rifles among the structures and heavy equipment.” After securing Provisor, the 129th attacked Manila’s New Police Station, another strongpoint. In the words of Robert Ross Smith, in his sequential history, “Triumph in the Philippines,” describes the area:

The New Police Station, two stories of reinforced concrete and a large basement, featured inside and outside bunkers, in both of which machine gunners and riflemen holed up. The 129th Infantry, which had previously seen action at Bougainville and against the Kembu Group, and which subsequently had a rough time against the Shobu Group in northern Luzon, later characterized the combined collection of obstacles in the New Police Station area as the most formidable the regiment encountered during the war.

The March 15, 1945 Lockhart Post Register reported that Pfc. Samuel Serrato had been reported killed in Manila, Philippines on February 14, 1945. He was killed in the taking the New Post Office and the complex of buildings around it. He was one of over 1000 GIs killed in the fight for Manila.

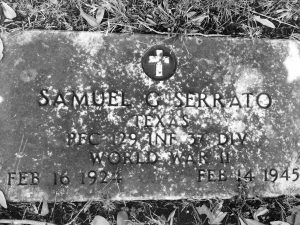

In 1949 Samuel’s body was returned home. Last rites were given at St. Mary’s Catholic Church on March 6. With American Legion Post 41 performing full military honors, burial was in St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery. At the request of the family, a military headstone marks Samuel’s grave.

REFERENCE NOTES: Ross Smith’s Triumph in the Philippines (US Army Center of Military History, 1963) and Battle of Manila Online’s website, www.battleofmanila.org were used extensively to capture the brutality of the Japanese defenders, and the difficulty of rooting out entrenched urban defenders. Thomas Huber’s “The Battle of Manila” (an essay within the website) was also used. Samuel’s Combat Infantryman’s Badge was reported as having been earned during the fight for HIll 129 on Bougainville Island. This probably is an error; I believe the fight was for Hill 700. See www.historynet.com/battle-of-bougainville-37th-infantry-battle-for-hill-700.htm. Sadly, I was never able to find a photograph of Samuel.

These stories are really insightful and I really appreciate the military history as well as the honor bestowed on those who were killed. I got your book and have really enjoyed it.

Thanks. Means a lot coming from you.

I’m Renee Montes great niece to Samuel Serrato my mom (Samuel Serrato’s nice) read this to me thank u for writing this I learned so much about my family we went to see him this memorial day to leave flowers and balloons thank u for your serves my great uncle Sam

I wish I knew more about your great uncle. Anything you could provide would always be appreciated. I’m always wanting to expand on my stories of those who died. Thanks so much for your kind words.

Todd Blomerth

This is my great Uncle. Big Dave Serrato was my grandfather. Very nice story, I never met him, but I did hear of his story.

Hello Todd, my name is Ernest Cortez, Samuel Serrato was my great uncle. His sister Estella Afanador, is my grandmother. Todd the story is beautiful and well written. Thank you very much for the detailed and beautiful story. Todd , I have a photo of Samuel I would like to send you.

Ernest