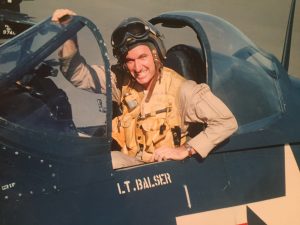

Lt. Bob Balser – F4U Combat Pilot – Korea 1952

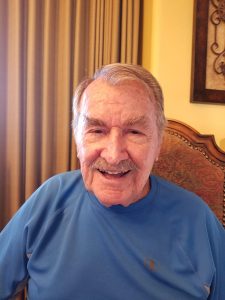

Bob Balser – 92 Years Young – 2016

BOBBY G. BALSER

From a Tough Childhood to the Best Life of Anybody-

And What a Life It Has Been

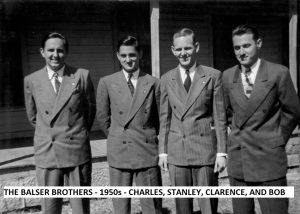

Bobby Balser is the third of four sons of Edward and Nora (Schulz) Balser. His oldest brother Clarence is 94. Older brother Stanley and the youngest of the four, Charles, have passed away. Bob (as he is also called) was born on a farm six miles northwest of Lockhart in 1924. Soon thereafter, his father bought a 250 acre farm in Karnes County, Texas. Tragically, in 1930, his mother and father died within six months of each other – Nora from tuberculosis, Edward from pneumonia. The four Balser boys were raised by their grandmother and a maiden aunt, Lonie Shulz in a house at 633 Pecos Street, just two blocks from the high school they would attend. Summers were spent working on various family members’ farms. He recalls the tough times of the Depression. Bobby’s childhood was not a very happy one. “No one had any money,” he says. “I don’t have too many ‘good’ memories” of that time he recalls. Perhaps not, but he was an honor roll student in school. In 1938, Bobby “Speed” Balser drove his “White Comet” to victory at “Dump Hill” in Lockhart’s first Soap Box Derby race, besting his life-long friend Jack Forrest Wilson. Deeply affected by the loss of both parents, and somewhat unsure of himself however, by the end of his schooling, Bobby was anxious to find his niche elsewhere. There were no jobs, and food was scarce. He graduated from Lockhart High School one month before his 17th birthday, and with Aunt Lonie’s permission, enlisted in the United States Navy. It was June of 1941. Less than six months later, America was embroiled in World War II.

After completing basic training, he became a Pharmacist’s Mate 2nd Class, and wound up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania assisting with physical exams at a Navy recruiting station. It was not something his enjoyed. The Navy needed pilots, and, though doubting he had much of a chance at being accepted into the flight training program, he applied. Much to his surprise, he was accepted. Even better, he breezed through flight training, and gained an huge dose of self-confidence, which has stayed with him to this day.

New aviation cadets with little or no college had to receive some burnishing, so that they could eventually, if lucky, be called ‘officers and gentlemen.’ Bobby spent the next several months taking courses at, among other places, the University of Washington, St. Olaf College, and Minot State Teachers College. Because of the rubber band effect of too few young men in pilot training, and then too many, what should have been a six-month training regimen lasted almost a year-and-a-half. Bobby qualified at Minot, North Dakota in a Piper Cub. Next stop – the University of Iowa for pre-flight training. Then, Naval Air Station (NAS) Grand Prairie, Texas, for primary flight training. Then south to Pensacola and Melbourne, Florida, where he transitioned to more complex aircraft, the Vultee BT-13 (nicknamed “the Vibrator”), and the much beloved SNJ “Texan.” Finally, he moved into the Navy’s primary carrier fighter in World War II – the tough Grumman F6F Hellcat. On October 12, 1944, the Lockhart Post Register reported that Cadet Bob Balser was now Ensign Bob Balser. The newly minted officer had  discovered his life’s calling.

discovered his life’s calling.

To get into the war in the Pacific Theater, new Navy fighter pilots had to be able to take off and land on aircraft carriers. This was (and is) dangerous and not for the faint at heart. In order to get the huge number of potential carrier pilots trained, the Navy improvised. Combat-ready aircraft carriers of all types were precious, so the government purchased two freshwater, side-wheel powered excursion steamers and stationed them near Chicago, Illinois. Rudimentary flight decks were added, and they were renamed USS Sable and USS Wolverine. Take offs and ‘traps’ (landings) were conducted seven days a week. Aircraft carrier landings require sufficient wind over deck (WOD). The two ships were slow, so if there were not strong enough winds on Lake Michigan, training was scrubbed, or the new pilots had to qualify in SNJ Texans, which required lower headwinds. Ensign Balser passed the tests, and by early 1945 was ready to get into the war. He would up in a replacement unit in Hawaii in March of that year. The beaches were closed, so apart from too much time at the Officer’s Club, all he and others did was fly, fly, fly. But Hawaii was far away from the islands being invaded by the Marines and Army. Bob opted for a photo reconnaissance class, in hopes of improving his chances of seeing some action. Off he went, to Guam, where he waited – again. Finally, he became of one of America’s Fast Carrier Task Forces. Stationed on various CVEs (smaller escort carriers, nicknamed “jeep” carriers), he became a member of Task Force 58. Combat and close air support missions were being flown – but Bob and others in photo recon, when they tried to ‘sneak’ out on combat missions with other squadrons, were told they were overqualified and ‘too valuable’ to be lost in combat. Basically, he and thousands of other American fighting men were expected to participate in the planned invasion of the Japanese main islands. The U.S. anticipated horrific losses of personnel when that happened. Everything changed when two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Suddenly, the war was over.

Lt. (j.g.) Balser rotated back to the states, and after some time spent at NAS Corpus Christi, was released from active duty. Taking advantage of the GI Bill, Bob enrolled in the Art Institute of Pittsburgh, and became an illustrator for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, where he was associated with Ray Sprigle. Sprigle had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1938 for uncovering that President Roosevelt’s nominee for the Supreme Court, Hugo Black, had once been a member of the Ku Klux Klan. (Sprigle did undercover stories, and in 1948 won international acclaim for a 21 part story – “I was a Negro in the South for 30 days.” His story can be found at http://old.post-gazette.com/sprigle/). Bob eventually decided that being an illustrator was not what he wanted to do with the rest of his life, but one has to be envious of his experiences with Sprigle and other reporters of such quality.

Bob remained in the Naval Reserve, flying with a squadron (VF 653) stationed in Akron, Ohio. The unit flew the gull-winged F4U Corsair. F4U Corsair was (and is) a thing of beauty. It would prove an ideal close air support fighter bomber in America’s next conflict. On June 25, 1950, communist forces from North Korea struck south, surprising and nearly overrunning poorly trained and armed Republic of Korea forces. President Truman rushed American forces to the peninsula, and eventually, American and UN forces pushed the North Koreans back – almost to the Chinese border. This brought in hundreds of thousands of Mao Zedong’s Red Army forces, and the Korean conflict settled into a proxy war of sorts

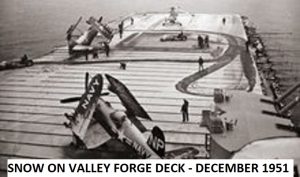

stationed in Akron, Ohio. The unit flew the gull-winged F4U Corsair. F4U Corsair was (and is) a thing of beauty. It would prove an ideal close air support fighter bomber in America’s next conflict. On June 25, 1950, communist forces from North Korea struck south, surprising and nearly overrunning poorly trained and armed Republic of Korea forces. President Truman rushed American forces to the peninsula, and eventually, American and UN forces pushed the North Koreans back – almost to the Chinese border. This brought in hundreds of thousands of Mao Zedong’s Red Army forces, and the Korean conflict settled into a proxy war of sorts pitting the United States and others against the communist regimes of North Korea, China, and the USSR. In the rush to downsize the military after World War II the overall ability to react quickly had reached shamefully dangerous levels. There were shortages of trained men, aircraft, and warships. The Congress authorized the calling up of reservists, including Bob’s squadron, which was assigned to Air Task Group One (ATG-1), and USS Valley Forge (CV 45), an Essex type carrier, slated for its third deployment in the icy waters off the coast of North Korea. The carrier launched Corsairs, A-1 Skyraiders, and jet-powered A-9 Panthers. Although Valley Forge had a steam-powered catapult, most of its ‘cat’ shots were reserved for its jets. Sailing from San Diego in August 1951, the ship arrived off North Korea with Task Force 77, on December 11. VF 653’s Corsairs took off from near mid-ship. They had 450 feet to get airborne. The Corsair was powered by a twin radial engine that put out over 2100 horsepower. It could carry eight bombs or rockets under its wings, and one 1000-pound bomb and drop tanks under its belly. Its armament was either .50 caliber machine guns or 20 mm. cannons in the wings. Needless to say, Bob preferred the 20 mm cannons.

pitting the United States and others against the communist regimes of North Korea, China, and the USSR. In the rush to downsize the military after World War II the overall ability to react quickly had reached shamefully dangerous levels. There were shortages of trained men, aircraft, and warships. The Congress authorized the calling up of reservists, including Bob’s squadron, which was assigned to Air Task Group One (ATG-1), and USS Valley Forge (CV 45), an Essex type carrier, slated for its third deployment in the icy waters off the coast of North Korea. The carrier launched Corsairs, A-1 Skyraiders, and jet-powered A-9 Panthers. Although Valley Forge had a steam-powered catapult, most of its ‘cat’ shots were reserved for its jets. Sailing from San Diego in August 1951, the ship arrived off North Korea with Task Force 77, on December 11. VF 653’s Corsairs took off from near mid-ship. They had 450 feet to get airborne. The Corsair was powered by a twin radial engine that put out over 2100 horsepower. It could carry eight bombs or rockets under its wings, and one 1000-pound bomb and drop tanks under its belly. Its armament was either .50 caliber machine guns or 20 mm. cannons in the wings. Needless to say, Bob preferred the 20 mm cannons.

Many of VF 653’s pilots were World War II combat veterans. Almost all but Bob were married. Given their anticipated duties, few had any misconceptions of the dangers they were about to face. David Sears writes:

In North Korea, the reservists would become bridge, road, and rail busters. Because that country lacked an industrial base, most of its supplies were hauled overland from Manchuria and the Soviet Union. Task Force 77 aviators specialized in the arduous, dangerous mission of destroying shipments and supply lines that coursed through the North’s rugged terrain. Day after day, they attacked railroads, roads, bridges, and the locomotives, trucks, and even ox carts moving along them.

Reserve Lieutenant Joe Sanko, married with one small son and another child on the way, wrote home that his chances of getting shot down would be “much greater than in the war with Japan.” Further, if he had to ditch, it would be in waters where “temp (sic) gets so low that a pilot can survive only five to eight minutes without a submersion suit.” Lt. Sanko would be killed when his aircraft was shot down by anti-aircraft fire on May 13, 1952. He never got to see his newborn daughter.

VF 653’s tour coincided with the horrible Korean winter of 51-52. Takeoffs and landings are dangerous at best. The squadron’s aircraft often came back with shot-up hydraulics, or ordinance that failed to release under the wings. Pilots would fly mission after mission, then the carrier would rotate to Japan for ten days of R&R. Then it was back into the grind of daily danger. Fortunately, in the words of Sears:

… the squadron was skippered by a hotshot Navy aviator named Cook Cleland, who, during the Pacific war, had flown Douglas Dauntless SBD dive bombers from the decks of the carriers Wasp and Lexington. After the war, Cleland, based in Akron, took up pylon air racing, initially flying production models of the Corsair but switching to a better-performing version of a Goodyear-manufactured Corsair purchased as surplus. Flying three of these muscular Super Corsairs, each sporting a 3,000-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-4360, Cleland’s team snatched a record-setting 396-mph victory in the 1947 Thompson Trophy Race. Beaten by Army aircraft the following year, Cleland’s team bounced back to sweep first, second, and third places in the 1949 race.

VF 653’s pilots had the flight helmets painted red with white polka dots. Then, because he was an illustrator, Bob recalled, “I had the job of sketching out a template for a grinning clown. The template was then hand-painted on the side of each pilot’s helmet. Because Ray Edinger was XO and was in charge of squadron discipline, his helmet got painted differently. His was a frowning clown.”

Smiling clowns belied the reality of VF 653’s existence. Pilots were killed or badly wounded. Pilots crash landed. Some were rescued. Some were not, and spent the remainder of the war in a North Korean POW camp (James Michener was imbedded with the Task Force, and efforts at rescue helped inspire his novel, The Bridges at Toko-Ri). Ground fire was an ever-present danger. Bob recalls, “We sometimes would attack behind the jets, which arrived at the target area first. We knew what we had to attack because we could see the antiaircraft bursts ahead of us!” Planes and pilots were lost to ack-ack and small arms fire. “I flew sixty combat missions,” Bob tells me. “My ship came home damaged in twenty of them.” Again, David Sears:

VF-653’s Korean War losses—13 pilots missing, killed, or severely injured, about 46 percent of the number first deployed—represented almost half of those sustained by ATG-1. As measured by total sorties flown, the results are equally stark: ATG-1’s airmen flew a combined 7,113; VF-653’s rate of losses per missions flown was twice as high as the air group’s overall rate.

Remains of a North Korean train – from Lt. Balser’s F4U Camera

The losses got to them all. “What was hardest was that we had flown together. I knew most of these men very well. It was very painful when we lost one. I lost two of my wingmen. Both bailed out and were captured.”

The squadron pilots pose on Valley Forge in July 1952, with 13 flight helmets for their fallen colleagues. Among the survivors are Cleland (back row, middle), Edinger (to his immediate left), and Balser (to Cleland’s right). (US Navy)

The squadron pilots pose on Valley Forge in July 1952, with 13 flight helmets for their fallen colleagues. Among the survivors are Cleland (back row, middle), Edinger (to his immediate left), and Balser (to Cleland’s right). (US Navy)

VF 653 rotated home in mid-June 1952. Its war was over. Lt. Bob Balser spent a year or so at Kingsville NAS, and was able to visit home. The Post Register of 25 December 1952 reported that the Balser sons had gotten together at Clarence’s house in San Antonio, and that “[t]his was the first time in about six years the family had been together.”

Bob applied to Trans World Airways in 1953. He started out as a $250-a- month co-pilot on a DC-3. He mandatorily retired in 1984, at age 60. By that time, he was a captain flying Boeing 747s to several continents. Belying the archaic FAA age rules, Bob continued to fly until he was 90. He sold his Cessna 177 two years ago.

Bob applied to Trans World Airways in 1953. He started out as a $250-a- month co-pilot on a DC-3. He mandatorily retired in 1984, at age 60. By that time, he was a captain flying Boeing 747s to several continents. Belying the archaic FAA age rules, Bob continued to fly until he was 90. He sold his Cessna 177 two years ago.

Bob married at thirty-three to Jacqueline (Jackie) Geffel, a beautiful Italian-American from Pittsburgh. They eventually settled in Scottsdale, Arizona. They had two sons. Jeffrey died

Bob married at thirty-three to Jacqueline (Jackie) Geffel, a beautiful Italian-American from Pittsburgh. They eventually settled in Scottsdale, Arizona. They had two sons. Jeffrey died  tragically in a vehicular collision in 1977. Stephen has followed in his father’s footsteps. He flies for American Airlines. Jackie passed away in 2015. Fortunately, Bob’s son and daughter-in-law Eileen live nearby. Bob is blessed with four grandsons. Don’t think he lets grass grow under his feet. After ‘retirement’, his group of friends tested every whitewater rafting area they could find. When you talk to him, you sense his spirit of adventure is still alive and strong. He is a joy to visit with. However, if you go too long, he will borrow his brother Stanley’s expression to sign off: “I’ve already told you more than I know.” His life exemplifies the courage and honor of the best of the Greatest Generation. Caldwell County should be mighty proud of Bob Balser and his achievements.

tragically in a vehicular collision in 1977. Stephen has followed in his father’s footsteps. He flies for American Airlines. Jackie passed away in 2015. Fortunately, Bob’s son and daughter-in-law Eileen live nearby. Bob is blessed with four grandsons. Don’t think he lets grass grow under his feet. After ‘retirement’, his group of friends tested every whitewater rafting area they could find. When you talk to him, you sense his spirit of adventure is still alive and strong. He is a joy to visit with. However, if you go too long, he will borrow his brother Stanley’s expression to sign off: “I’ve already told you more than I know.” His life exemplifies the courage and honor of the best of the Greatest Generation. Caldwell County should be mighty proud of Bob Balser and his achievements.

The story of Bob’s time in Korea comes from interviews with him, as well as Smithsonian Air and Space’s article of January 2013 – “The Ordeal of VF-653: From a Navy Reserve pilot’s letters home, a picture of the darkest days of the Korean War” by David Sears http://www.airspacemag.com/military-aviation/the-ordeal-of-vf-653-127029178/?page=1