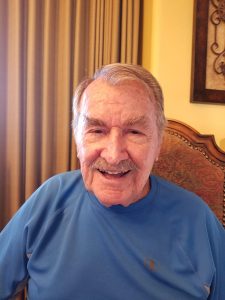

James Leslie Dilworth’s motto is, emphatically “it is not the years in life that count – it is the life in the years that count.” He certainly has lived his life accordingly. Leslie, as he goes by will be 100 years young on January 27, 2015. His life is a celebration of the endless possibilities for achievement through hard work and determination.

In Texas the Depression didn’t start in 1929. For rural Texans, times were tough long before the stock market crash of 1929. Leslie was a child of those times. His mother, Beulah Hodges, and father, John Marion Dilworth, were from the Belmont area, where John was a rancher and livestock trader. Leslie’s only sibling, his sister Grace Loise, was ten when he was born. His dad moved the family from Belmont to Luling where he also went into the feed and grocery business. Sadly, Leslie’s mother died when he was ten. When Leslie was fourteen he lost his sister. Loise and her husband were visiting in Arkansas when she became gravely ill. John took the train to see his daughter, and then sent a telegram to Luling for Leslie to come as well. Loise, knowing she was dying, wanted to see her baby brother. Leslie’s first trip from home ended abruptly in Northeast Texas when another telegram was received telling him to return home. His sister had died before he could see her.

Leslie doesn’t remember not working. John Dilworth bought and cottonseed in his small grocery store, which required stirring to avoid spoiling and spontaneous combustion. By the age of ten, Leslie was turning cottonseed after school, and ‘there was tons of it.’ At twelve he became a Western Union messenger using his new bicycle. When school was out for the summer he chopped and picked cotton and hauled hay, many times for an African American gentleman and friend of the family, Henry Hutcheson.

John Dilworth remarried a couple of years after Beulah’s death. Leslie and his step-mother weren’t very close. Leslie’s step-mother did not drive. Wanting to visit some of her family in Dallas, John solved the problem by assigning Leslie as her chauffeur. Although never before having driven outside of Caldwell County off he went to Dallas. He was fourteen. There was a bright side – he got to go the Texas State Fair.

Leslie attended schools in Luling, but did not finish the 9th grade as “the Luling schools felt they could do better without me.” I get the impression that he must have been a handful to deal with! His maternal aunts decided he needed some better supervision than what was being offered in Caldwell County, so off he went to live with one of them in Galveston, where he says he “coasted for a while.” That is hard to believe. Soon, he was back in Luling, and with no school to distract him, was delivering 50 pound blocks of ice. He moved back to Galveston where he worked 72 hours a week in a filling station, then on a dry-dock, and finally at the Buccaneer Hotel as a bellboy, where he often made 5 dollars a day in tips! This was a princely sum.

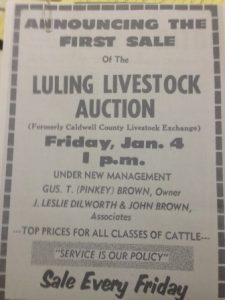

Buying and Selling Cattle – 1940

1974-In Business in Luling

Returning to Caldwell County, he first worked on a pipeline crew and then went into the cattle and hog business with his father. He also got married in 1939 to Lennah Martha Bright. They were life partners until her death in 2001. Leslie and Lennah moved to San Antonio, where he worked for the Union Livestock Commission, while also taking care of his own cattle in Caldwell County. He and Lennah lived in San Antonio for 49 years, most of the time at 540 Westminister.

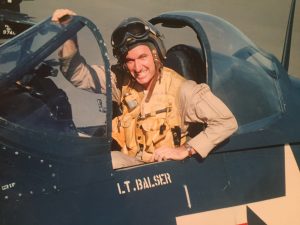

In 1940 time came for all young American men to register for the draft. As Leslie was married, he did not receive a call-up notice until 1943. He could have claimed a deferment, but instead answered Uncle Sam’s call on May 18th, 1943. His initial training was at Republican Flats adjunct to Ft. Riley, Kansas, a Cavalry Replacement Training Center. Once through basic and advance training, he was promoted to corporal, and then to sergeant. Because of his maturity and an excellent training record, he was assigned as a training sergeant, where he met many interesting men, including fighter Joe Lewis.

After Ft. Riley, he was transferred to Gainesville, Texas for additional training. He applied for airborne training. The Army in its wisdom instead decided to make him an officer and a gentleman in its Armor branch, and sent him to Ft. Knox on November 27, 1944 to in its officer training program. He graduated on May 5, 1945. While at Ft. Knox, Leslie made friends with some Colombians, who would eventually return to their country. He was promised a high-paying position in the Colombian Army, once the war was over. He politely decided against that, a  Training Men on Armored Reconnaissance

Training Men on Armored Reconnaissance

decision he still is relieved to have made. As a freshly minted second lieutenant, he was re-assigned to Ft. Riley. There, he briefly trained soldiers in armored reconnaissance and operation of various types of tanks. As a tank commander perched in the cupola, he would signal the driver-trainee with foot pressure to his back. Left foot in back – turn left. Right foot to the driver’s back – turn right. Stop – both feet to the back. You get the idea. One of his trainees wasn’t paying attention and headed for a precipice. Left foot – nothing. Right foot – nothing. Leslie used both feet to signal stop. Nothing. Then both feet HARD! Nothing. Almost crushing the driver with his feet, the tank continued over the precipice, with the cupola ring bruising Leslie badly. “I’m glad I didn’t see that fellow again.”

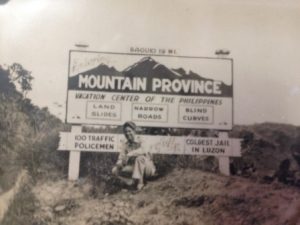

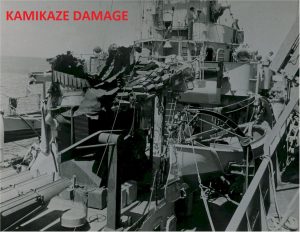

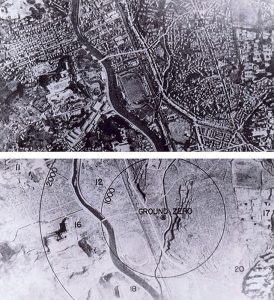

By now the war in Europe was over. All eyes turned to the Pacific, where the war with Japan still raged. America and its allies began preparation for invasions of Japan’s home islands. Bloody battles on Iwo Jima and other islands had left thousands of young American boys dead and wounded. On and in the waters around the island of Okinawa, the Americans were locked in the most brutal land and sea battle of the Pacific Theater. In the meantime, 2nd Lt. Dilworth was shipped to Ft. Ord, California for invasion training. Assigned as a transportation officer, he spent 30 miserable days on a troop transport, landing in the Philippines in late July, 1945. Like every other soldier, sailor and marine in the Pacific he dreaded what was about to occur. Harry Truman is Dilworth’s favorite president. Without question, he believes that President Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bombs on Japan saved his life and those of millions of others. He was at Base

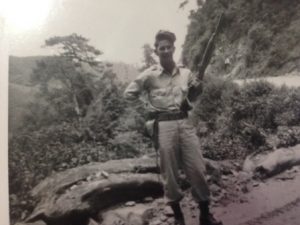

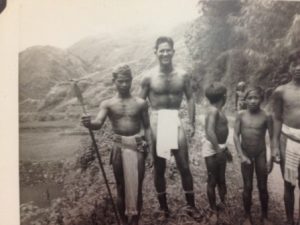

With Bontoc Tribesmen in the Highlands

With Bontoc Tribesmen in the Highlands

Supervising Japanese Prisoners of War

Supervising Japanese Prisoners of War

“M” near Lingayen Bay on Northern Luzon when Japan surrendered. Assigned to a truck platoon of the 869th Heavy Automotive Maintenance Company, Leslie helped ensure that the neglected and war-battered Philippine transportation system functioned. Huge amounts of equipment were being moved to ships to be returned to the US and convoys had to deal with an often non-existent infrastructure. Leslie recalls when a tractor-trailer rig got stuck trying to make a curve on a mountain road. When efforts to free it failed, the men just jacked one side up and rolled it off the road and down the mountain. It was that kind of time and place. Japanese POWs, awaiting repatriation were used to build and repair roads. The Americans hired Filipinos to work in many capacities. The mountainous areas of Luzon were populated by many different tribal groups, including the Igorot people. Comprised of several sub-groups, including the Bontoc, they were small in stature. These remarkable “mountain people” or Cordillerans, were former headhunters. They worked closely with Americans as guides, porters and laborers. Leslie’s photo scrapbook shows his deep interest it their lives, and the mutual respect this American and his Bontoc friends had for each other.

By 1945, there were several guerilla groups fighting the Japanese, collaborators, and sometimes, each other. One very large group was the predominantly Marxist Hukbalahap (“Huk”) movement. Ray Hunt, an American who led a band of guerillas, had little use for the Huks. He was quoted by William Breuer in The Great Raid: Rescuing the Doomed Ghosts of Bataan and Corregidor:

My experiences with the Huks were always unpleasant. Those I knew were much better assassins than soldiers. Tightly disciplined and led by fanatics, they murdered some Filipino landlords and drove others off to the comparative safety of Manila. They were not above plundering and torturing ordinary Filipinos, and they were treacherous enemies of all other guerrillas (on Luzon).

There were tens of thousands of Japanese in the Luzon mountains on VJ Day. Most surrendered. Some did not. The “Huks,” as they were called, often asked for American weaponry and equipment to assist in hunting down rogue Japanese in the mountains. As the Philippines were to be given its independence in 1946, the Huks rightly feeling they were not going to be given a role to play in the new democracy, also began attacking American convoys. Leslie was in charge of security on some of the convoys, which were moving American supplies back to ports for trans-shipment to the United States. One time, he and other Americans got wind of the location of a possible weapons cache in a village. Filipino houses were built on platforms. As Leslie was about to enter one of the village’s houses, its owner became quite excited and began shouting loudly in Tagalog, the chief Filipino language. Not understanding Tagalog and convinced by the man’s behavior that he was on the scent of contraband, Leslie entered the house, only to fall through it. The man had merely been trying to warn him that his floor was rotten!!!

There was not a day that went by that Leslie did not face Luling, and wish that he was home. Once discharged, Dilworth returned to the profession of cattle buying. He owned and operating

auction barns and feed lots all over Texas. He partnered in ranches in South Texas, and appraised herds for the Houston Agriculture Credit Corporation. Leslie helped Gus “Pinkey” and John Brown re-open the Luling Auction Barn in 1974.

His work schedule never remotely came close to an eight hour day. Often up at 3 am, he would move cattle, work with auction houses, and care for his own cattle in Caldwell County. The profit margin on cattle is at best a slim one. Leslie transported, bought and sold thousands over the years. He was a savvy businessman who wasn’t afraid to take chance on a new project – as long as it involved cattle. A friend to ranchers all over the state, he has known some quite prominent ones, such as Dolph Briscoe. All the time he was a loving husband to Lennah and father to his only child Virginia (Sofge). Virginia grew up asking, “Why don’t we keep the pretty cows and calves, dad?” His answer was simple – the pretty ones sold better.

Leslie “retired” at the age of 80, and tended to the home place in Caldwell County and its cattle until the age of 95. He would still be working and tending his cows, except that his legs quit cooperating with him a few years back. He has had to pass those duties along to his daughter and her husband. He herds a wheel chair now, and resides at Lockhart’s Parkview Nursing Home. Looking and acting like a man thirty years younger, this proud father, grandfather and great-grandfather will celebrate his 100th Birthday with a party on the 25th of January at Parkview. If you get a change, come by and see him some time, and congratulate this remarkable man on a life well lived. And thank him for his service to our country during World War II.