WILLIAM JEFFREY

VAN HORN

William Jeffrey Van Horn was born on January 12, 1915 to Louis and Etna Malissa (Jeffrey) Van Horn. A typical youth of the McMahan area, he and his brothers Valon (“Po”), Doise and Leonard were active in school sports. Before closing down in the late 1930s, McMahan’s high school only went through the 10th grade, and was an “eight month school” according to Mr. Curtis Owen. Lockhart High School was an accredited “nine month school” that went through the 11th grade. William and two or three other good football players from McMahan ‘miraculously’ were provided an auto, so they could travel to and attend school (and more importantly, play football) at Lockhart High School. William also played on Lockhart High School’s basketball team. By all accounts, he was a very likeable young man.By 1940, the couple had two children, Patricia Jean and William Jeffrey Jr. and the family was living in Travis County, where Van Horn worked on a dairy farm. The marriage foundered, and the couple divorced. By 1943, he had remarried, this time to Gwendolyn Rogers of Austin. He was employed by Austin Transit Company. In May of 1944, at the age of 29, he enlisted in the Marine Corps. He was shipped to Camp Pendleton, California where he was assigned to the 2nd Training Battalion. After boot camp, he received additional training as a mortar man, and then was shipped overseas with the Tenth Replacement Draft. He was assigned to Company I, Fifth Marine Regiment, First Marine Division (the Division’s men called themselves the “Old Breed”). He arrived in the Pacific war zone after the Peleliu landings. The 5th Marines were badly bloodied in fighting there, and William was one of hundreds of replacements filling the ranks of the depleted unit.

Between October of 1944 and April of 1945, the First Marine Division rebuilt its strength while training on the island of Pavuvu for its next combat mission. Its final battle of the war would prove to be its most horrific.

By March of 1945, Germany was within weeks of surrendering, yet there was no sign that Japan would do the same. As a result, massive efforts were in force to compel Japan’s submission. This meant attacks closer and closer to the home islands. And the closer the fighting came to Tokyo, the more deadly (if that was possible) it became. Japan had made clear to the Allies that it had no intention of surrendering. To prove its point, its military increased its efforts at training civilians, building additional fortifications, and using suicide tactics against naval units.

Okinawa is the main island in the Ryukyu Island chain, and lies only 350 miles from Japan’s southern home island of Kyushu. Inhabited for over 30,000 years, the Ryukyus eventually created an independent empire before 700 A.D. Forced to give tribute to the Shimazu clan of southern Japan in the 1600s, it retained much independence until the Meiji Restoration of 1868. It became a prefecture in 1879 and the Kyushu islanders were granted the vote at the national level in 1912. Although the islanders were considered less than “pure” in many Japanese eyes, the fact remained that the islands, and especially Okinawa, were Japanese to outsiders. Thus, it was paramount in importance to the Japanese that the American be so bloodied there that no attempt would be made to invade the home islands. They prepared accordingly.

American Forces Landings and Attacks North and South

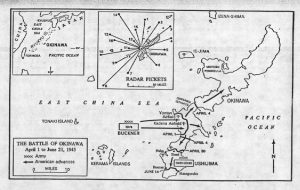

The Allied invasion plan of Okinawa was called Operation Iceberg. The Okinawan landings on the April 1, 1945

were the largest conducted in the Pacific. A third the size of Rhode Island, Okinawa stretches 66 miles, with its maximum width of 20 miles. Within three days, the island had been cut in half. Where were the defenders? The six American divisions – four Army and two Marine – soon found out. The main Allied forces swung south, and immediately ran into the first of layered defenses and determined resistance. By the time the 81 day battle was over, more than 12,000 GIs, marines and sailors were dead and 50,000 wounded. Kamikaze attacks on ships sunk or damaged scores. It was the most savage fighting of the Pacific. Over 100,000 Japanese soldiers and marines died, and Okinawans, many pressed into service, compelled to serve as human shields, or forced into mass suicides by the Japanese died in untold tens of thousands.

The Old Breed’s first month of action was relatively easy. But after securing airfields in the middle portion of the island and subduing defenders on several nearby small islands, the First Division was put into the line to replace Army units and ordered to attack an area known as the Awacha Pocket.

Historian Eric Hammel writes:

The infantry units that the 1st Marine Division replaced had been ground down to regiments little larger than battalions, and battalions little larger than companies. Dead ahead was the bulk of a Japanese infantry division holding a defensive sector the island command had just reorganized to higher levels of lethality. On the division’s first full day on the line, the weather turned cool and rainy, a state that would prevail into July…. This baptismal day on the southern front was emblematic of the fighting that ensued. The Japanese made excellent use of broken ground and other natural cover, and the Marines were either stymied or fell into dead ground from which they could either advance or from which they had to withdraw to maintain a cohesive line against the uncanny knack the defenders showed for mounting enfilade movements. On May 3, the 5th Marines advanced more than 500 yards in its zone, but the 1st Marines was pinned down with heavy casualties, so the 5th had to pull back several hundred yards in places. There simply was no point at which the Marines could gain adequate leverage — the same scenario the replaced Army divisions had faced in their battle.

The war classic With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa, (later part of the basis for the HBO miniseries “The Pacific”) was written by E.B. Sledge, also a member of 3rd Battalion and a mortar man. He may have known Van Horn. He was a hardened veteran who had seen just about every horror of war on Peleliu, and as the 5th Marines approached the Japanese defenses, there was no bravado. As the regiment carefully moved into the line to relieve an Army unit that had been badly bloodied:

I was filled with dread….Ahead we could hear the crash and thunder of enemy mortar and artillery shells, the rattle of machine guns, and the popping of rifles… Shortly a column of men approached us on the other side of the road. They were the army infantry from the 106th Regiment, 27th Infantry Division that we were relieving. Their tragic expressions revealed where they had been. They were dead beat, dirty and grisly, hollow-eyed and tight-faced. I hadn’t seen such faces since Peleliu. As they filed past us, one tall, lanky fellow caught my eye and said in a weary voice, “It’s hell up there, Marine.”

Rains of the fast arriving wet season then hit, turning everything into goo. It was in the rain and mire of that I Company was committed to close a gap in the line of attack. It was here that on May 3, 1945 that William Jeffrey Van Horn was killed, probably by mortar and machine gun fire that drove the 5th Marines back and limited the regiment’s badly mauled companies’ two days’ advance to 300 yards.

Flamethrower “Ronson” Tanks and Enemy Position

A Marine Takes Aim Against a Japanese Sniper

The Lockhart Post Register front-page story of May 17, 1945 was very brief. It merely recited that Mr. and Mrs. Louis Van Horn of McMahan had just received word from the Marine Corps that their son had been killed on Okinawa on May 3, 1945. Van Horn was buried with thousands of other Americans on the island that had fought so hard to take.

In 1949, and at the request of the Van Horn family, William was disinterred and his body brought back to Texas for reburial in the Jeffrey Cemetery. At two p.m. on February 18, 1949, services were conducted by Elder Richard Cole and Reverend Ed V. Horne. Military honors were given by Henry T. Rainey Post No. 41 of the American Legion. Casket bearers were A.C. Lankford, L.S. New, Herman Becker, Vernon Woods, Tilmon Jeffrey, and Jack Stubbs. On March 3, 1949, the Van Horn family’s note of thanks was printed in the Post Register.

William Jeffrey Van Horn Sr. was 30 years old when he died.

Please contact me as i have some info for the family.

my email is blomertht@gmail.com