JOSEPH BENNETT COOPWOOD

by Todd Blomerth

The December 9, 1943 edition of the Lockhart Post Register read “MAJ. JOE COOPWOOD KILLED IN ACTION.” This was a tragic day for Lockhart, because Joe was one of the town’s most beloved citizens. Because of his unique background, training, and service to his community, Coopwood’s death dealt a tremendous blow to the Caldwell County community.

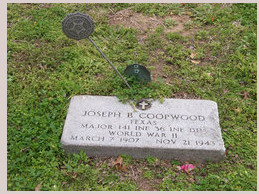

Major Joseph Bennett Coopwood was the regimental surgeon for the 141st Infantry Regiment of the 36th “Texas” Infantry Division. He was born in Lockhart on March 7, 1907. His mother was Eva Putnam Coopwood and his father was Dr. Thomas Benton Coopwood. Joe was destined to follow in his dad’s footsteps. He graduated from Lockhart High School, then spent one year at the Virginia Military Academy before enrolling at the University of Texas for two years. He then attended Baylor University College of Medicine and received his Doctor of Medicine in 1930. At the same time he was commissioned into the Medical Officers Reserve Corps. He interned in San Antonio and did his residency at the Cumberland Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. He then came home to set up his medical practice. On December 19, 1936 he married Kate (“Tiny”) Ellis Lipscomb. They would have two children, Tommy and Kate. A devout Methodist, he served on Lockhart’s First Methodist Church Board of Stewards. He was also a Mason.

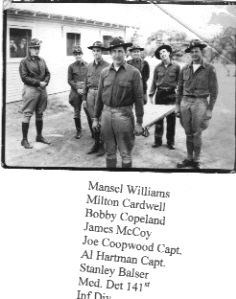

At DeRidder, La. In 1940 141st Reg’t Medical Detachment -Lockhart 1941

He was one of the organizers of the 141st Infantry Medical Detachment, which had its armory in Lockhart. When the 36th Division was nationalized in November 1940, he quickly rose through the ranks, and on December 24, 1941 was promoted to major. The Division went into training at Brownwood, Texas and later in Florida. Some of the medical detachment trained in Colorado and were loading a bus for their first ski trip, sponsored by the local chamber of commerce, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. The ski trip never happened, and for many of the detachment there would never be another opportunity.

In early 1943, the division was sent to Massachusetts, and then shipped to North Africa for further training. Loading on ships at the port of Oran, it then became part of the most controversial front in the European Theater – the attack on the Italian mainland. Labeled by Winston Churchill as the “soft underbelly” of the Axis powers, the invasion took place near the port of Salerno, approximately one quarter of the way up the west coast, and south of the city of Naples. In describing Italy, author Rick Atkinson stated it was “eight hundred miles long, [and] it was the most vertebrate of countries, with a mountainous spine and bony ribs.”

The Americans and British had finally taken the island of Sicily in August of 1943, and the Italian government bowed out of the war soon after. Substantial numbers of troops (and just as importantly, landing craft) were siphoned off in preparation for the 1944 D-Day invasion of France from England. Assuming that the surrender of Italy would allow the Americans to ‘walk in’, Allied planners gave little thought to what would happen if the Germans chose to defend Italy in spite of the Italians, which they immediately set about preparing to do.

To make matters worse, British Field Marshal Montgomery had cut off the American axis of advance in Sicily by giving priority to his own troops. In doing so he (and the inaction of Allied air forces and navies) gave the Germans ample time to evacuate over 40,000 troops across the Straights of Messina onto the Italian mainland. American General Omar Bradley would later declare Montgomery’s conduct “the most arrogant, egotistical, selfish and dangerous move in the whole of combined operations in World War II.”

This mistake would have deadly repercussions for the Allies at Salerno. Landing without preparatory naval bombardment, the 36th Division’s regiments were cut to ribbons. The 36th’s commander, General Walker stated the 36th lost 250 men killed in one half day defending the beachhead! There were so many dead that, in the words of an Army engineer, “They’ve placed the graveyard, the latrines and the kitchen all in the same area for the convenience of the flies.”

Dr. Coopwood was one of the medical personnel working on Red Beach. “The evacuation hospital near Red Beach was so overcrowded that many patients lay “along the walls of the tents with their heads inside and their bodies outside.”

As regimental surgeon, Dr. Coopwood saw every conceivable way a man could be killed or wounded. For many, the only treatment was morphine to ease their dying, with an “M” printed on their foreheads with iodine.

On Sicily, famed correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote “Dying men were brought into our tent, men whose death rattle silenced the conversation and made all of us thoughtful.” He saw that a trench outside the surgical tent was “filled with bloody shirt sleeves and pant legs the surgeons had snipped off wounded men.” He remembered one dying man in particular:

The dying man was left utterly alone, just lying there on his litter on the ground, lying in an aisle, because the tent was full…. The aloneness ofthat man as he went through the last minutes of his life was what tormented me.

Salerno would be as bad. Italy would be worse.

While the Salerno beachhead was in grave peril, Montgomery (whose troops had landed in the boot of Italy even though everyone knew there were virtually no German troops there) slowly moved northward, ignoring desperate pleas from the troops at Salerno.

After the botched landings at Salerno, German Field Marshal “Smiling” Albert Kesselring, a defensive genius, withdrew his troops to a series of defenses dubbed the Winter Line. The 36th Division’s official history tells of the German delaying action across the whole of Italy. The 36th was given a brief respite then moved back into the lines. “It rained the November night the 36th moved up to re-enter the line near Mignano, where Highway 6 and a main railway cut through a narrow pass into the Liri Valley running north toward Rome.” Rain, mud, cold, artillery, snipers, and incomprehensible orders to take hills that hid German fortifications were the order of the day.

On November 15, 1943, the division moved into the Camino Maggieore hill mass guarding the Mignano Gap. Rains turned the mountainous terrain into a horror. What donkeys and mules not already requisitioned by the retreating Germans were dragooned into service. Where donkeys couldn’t go, supplies were carried by hand.

One of Doctor Coopwood’s section sergeants was McMahan’s Curtis Owen. Sergeant Owen ran the 141st Regiment’s second battalion aid station near the front. It wasn’t necessary for regimental surgeons to visit these aid stations – there was enough to do elsewhere, and the risk of being killed increased dramatically the closer to the front. In fact, according to Owen, he never saw any other regimental surgeon do it. But, said Owen, “Major Coopwood wasn’t like other doctors. He came up and checked on us every other day. He had a high regard for his people.” Owen said that the last words he heard from Major Coopwood were, “I’ll see you day after tomorrow.” Coopwood never came back. He was killed the next day by a long range artillery round that struck his jeep. In all probability his death could have been avoided. When the Italians surrendered, some units came over to the Allied side. Bivouacked near the 141st Regiment’s headquarters, they exhibited poor camouflage practice. More than likely they were seen by German spotter aircraft and the area then targeted. He was killed on November 21, 1943. He was 36 years old.

His death disheartened those who knew him. Curtis Owen had joined the Medical Detachment in Lockhart in 1940 out of respect for Dr. Coopwood: “He was a father figure to us. He had taken country boys and made soldiers out of all of us.” Lockhart’s Stanley Balser was his driver. He suffered from chronic asthma that had flared up the morning of November 21st, requiring him to report to sick call. Until the day he died, he often questioned why he lived and the man he so admired died.

Dr. Coopwood’s death hit hard. The The Coopwood house faced that of Peck and Martha Westmoreland on Lockhart’s Maple Street. Peck, a pharmacist was home eating lunch with Martha when he saw Western Union auto drive up to the Coopwood house. Peck later told his son Brad that he never felt so sick in his life, because he knew what the telegraph company’s messenger’s appearance meant.

Harry Hilgers, then attending Lockhart High School recalled news of the death being “received like a bombshell in the student body.”

Major Coopwood was buried in Italy. After the War, his body was disinterred and brought home to Texas. All businesses in the city were closed from 3:30 to 5:30 on October 1, 1948, as last rites were held at McCurdy’s Funeral Home. American Legion Post 41 members assisted in the ceremonies there, and at the Lockhart Cemetery, where he was laid to rest. His funeral was not just a local event. George Ohlendorf, then a young boy, lived on a farm near Polonia, north of Lockhart. He watched buses and cars carrying 36th Division veterans to the last rites streamed south out of Austin. An Honor Guard, with men from as far away as Lampasas, consisted in part of men he had commanded in the 141st Infantry Regiment’s medical units. Curtis Own represented the McMahan community. A caduceus made of mums “from the boys in the Medical Detachment who served overseas with him” decorated the chapel, in the words of the Post Register. His casket bearers included Stanley Balser and Wesley Dalton.

In one of the memorials subsequent to his death, the Lockhart Business Men’s Club stated, “His civilian and professional life made of him a good citizen. The when, where and how he died makes him a patriot. Such a man could be nothing less than a good husband, and one worthy of the name father.”

Mrs. Coopwood never remarried. She retired as a schoolteacher, as did her daughter. Joe Coopwood’s son Tom became a physician. His grandchildren included three physicians and a nurse.

(Much thanks to Dr. Tom Coopwood for providing his dad’s photo)

(Rick Atkinson’s The Day of Battle provided much information on Sicily and Salerno)

POSTSCRIPT: Brad Westmoreland called after reading the article. His mother and father lived across from Dr. Coopwood on Maple Street. They were eating lunch when Western Union drove up. Peck told his son Brad that he never felt so sick in his life at what he knew he was going on across the street.

POSTSCRIPT: An email from Harry Hilgers:

Todd: I have read almost every book and article written about WWII and have added my own experiences to that and found your article in the Post Register as the most riveting story I have read. I was a student at LHS when the news came about Major Coopwood and in a class with his sister, Julia, who was my instructor in Spanish class. The news was received as a bombshell in the student body which met once per week in Adams Gymn to hear the latest news from the front. There was a large flag mounted by the stage with blue stars for every veteran serving and gold stars for those who were killed in action. It was a vivid and sad reminder to all of us of how close we were to being included in the casualties. Major Coopwood was, because of his background, his family history, and his achievement something akin to Sir Galahad of King Arthur’s Court so that his death was keenly felt by all. His picture can be seen in the foyer at the Legion. You have a gift as a writer of keeping the reader’s interest at a very high level and this article was, perhaps, your best example of that talent. Keep those articles coming. Harry

POSTSCRIPT: Discussion with George Ohlendorf on 7-1-13

As a child living near the Rogers Ranch, he can remember Dr. Coopwood’s funeral in Lockhart because of the many busloads of 36th Division veterans that attended from Austin.

POST SCRIPT

A wonderful tribute and you made a fine Dr. Joe! I will put these with my early years memory treasures.

(From ‘Tiny’ Singleton who I contacted on Walton Copeland in March of 2014)

My father, James Stedman, DDS, and Joe Coopwood were in the same office space above the Corner Drug Store and were friends. I was and am a good friend of Tom Coopwood, MD, son of Joe and Tiny. Although I was only 5 the day Western Union delivered the news, I still remember the call my parents got to let them know. Like the Westmorelands, they were devastated. They had bought me some Christmas gifts and I was badgering them to let me look. After the call, they didn’t care and just let me look. Then they left to go over to the Coopwoods right across the street.

My father, James Stedman, DDS, and Joe Coopwood were in the same office space above the Corner Drug Store and were friends. I was and am a good friend of Tom Coopwood, MD, son of Joe and Tiny. Although I was only 5 the day Western Union delivered the news, I still remember the call my parents got to let them know. Like the Westmorelands, they were devastated. They had bought me some Christmas gifts and I was badgering them to let me look. After the call, they didn’t care and just let me look. Then they left to go over to the Coopwoods right across the street.

Thanks jim

Just added some more

Still learning

Putting all in book form

Todd

My father, William (Bill) Alexander served in the 141st Medical Detachment with Dr. Coopwood, whom he called the best and bravest man he ever knew. He said he was always looking out for the welfare of his men, even when it frequently put his own life in peril. My dad spoke about Dr. Coopwood’s heroic service and tragic death so many times, always with reverence; it was a story he wanted to make sure that I knew and remembered.