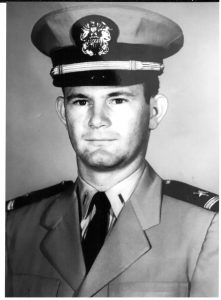

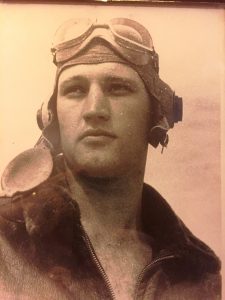

ROBERT “BOB” PEEBLES

A Peaceful Man Who Has Witnessed the Horrors of War

By Todd Blomerth

Bob Peebles was born on January 19, 1922, in the small town of Alvin, Texas. His father worked for Gulf States Utilities, and the Peebles family lived and around the Alvin area all his early years. Bob was the youngest of three children. His brother Howard (now deceased) was ten years older. Marjorie (Wyatt), who now lives in Edna, was four years older. Bob attributes much of his success academically to Marjorie. “She became my ‘teacher,’” he tells me. “We would walk home from school. Starting when I was in the first grade, Marjorie would then sit behind an apple crate on the screened porch, and make me learn reading, arithmetic and writing. She was relentless.” Bob’s grandfather had passed down many classics, so Marjorie used some as her primers. He still remembers with clarity certain portions of stories by Charles Dickens, because they were found on pages holding his grandmother’s pressed flowers, and “we were told to be very careful with those flowers.”

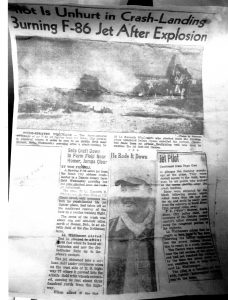

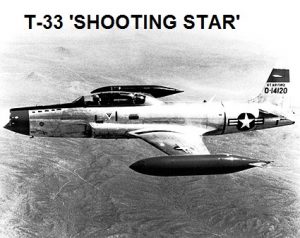

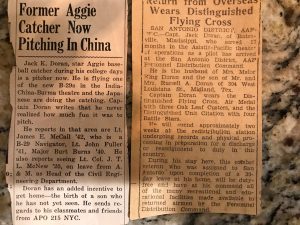

Bob attended Alvin High School, and was voted ‘most popular boy’ in 1938 and “Best All Around” student in 1939. He played baseball and basketball, but his favorite sport was football. He graduated in 1939 and then enrolled at the University of Texas taking pre-med courses and playing freshman football. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, he rushed to enlist in the U.S. Navy. Although he “hadn’t been within five miles of an airplane,” he signed up for naval aviation training – and flunked the physical! He had varicose veins in and around his knees from playing football. Disheartened, he hunted down a physician to fix the supposed ‘disability,’ had minor surgery, and finally, on May 1, 1942, passed the physical. He was now officially a naval aviation cadet. For the next year, Bob moved through the various phases of aviation training starting in Luscombe single engine trainers, then graduating to PT-17 Stearman “Kaydets” (nicknamed “the Yellow Peril”), to Vultee “Vibrators,” and finally to the SNJ “Texans.” His class ranking allowed him the choice of Navy or Marine Corps aviation, so he chose the Corps. Part of Flight Class 9A (42-C), he received his aviator’s wings and commission as a 2nd lieutenant at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi. On the way to combat aircraft, he took a short detour, flying C-47 cargo aircraft. He credits his time in that beloved aircraft’s cockpit for allowing him to hone his navigation skills. Apart from occasional ‘radio ranges’ there were few electronic aids in those days; no GPS, FM radios, or omni-directional beacons. Dead reckoning was a skill that would prove invaluable in the Pacific theater.

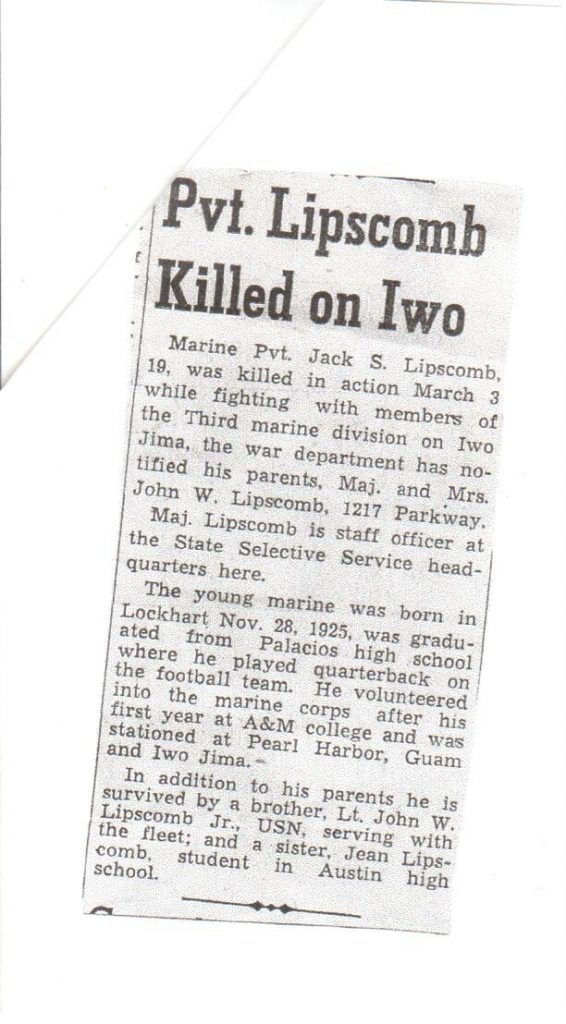

During flight training, Bob met Lesley Valentine Strandtman, whose family lived outside of Lockhart, Texas. Strandtman was a Fightin’ Texas Aggie and member of the Aggie Band. The two put college rivalries aside and became good friends. Besides a life-long friendship, Valentine’s younger sister, Adeline (“Addie”) Marie would eventually become Bob’s wife in 1946.

Bob’s next duty station was Cherry Point, N.C. After a short time there, he was ordered to El Toro Naval Air Station, California where he transitioned into the Grumman F4F Wildcat, one of the first modern fighters able to take on the more nimble Japanese fighters. It still had some primitive mechanisms, such as having to retract landing gear by 27 hand cranks!

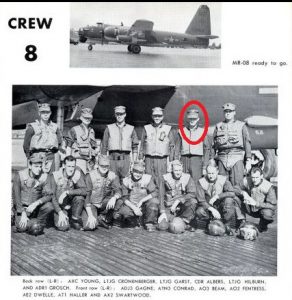

Lieutenant Peebles was assigned to Marine Corps VMF 114, a fighter squadron that was equipped with one of the premier American fight aircraft of World War II – the Vought F4U Corsair. The Japanese would soon describe the aircraft as “Whistling Death.” The new squadron’s top three officers were veteran combat pilots;  the rest of the pilots were newly minted. VMF 114 was shipped to Hawaii where it continued training. The U.S. Navy had turned back a Japanese invasion of Midway Island in June 1942. The island’s location in the Northern Pacific was of strategic importance. As a result, combat units continued to defend the tiny patch of land. In December 1943, VMF 114 was shipped to Midway Island for three months. Then it was back to Oahu to prepare for shipment to Espiritu Santo, a staging area for the Americans’ advances against the Japanese. After additional flight and survival training. VMF 114 moved into its first combat area. Flying from the Green Island group near Papua New Guinea, the squadron suffered its first losses. The Japanese had created a huge base at Rabaul on the island of New Britain. By 1943 there were over 100,000 enemy stationed there. Although Rabaul would be ‘bypassed,’ American air and naval forces kept up unremitting attacks on it and on another enemy base at Kavieng. The Americans did not dare allow an exceeding well trained and increasingly desperate enemy any opportunity at disrupting our advances elsewhere. Weather, combat and air accidents resulted in VMF 114’s loss of nine pilots. The reality of war was now sinking in.

the rest of the pilots were newly minted. VMF 114 was shipped to Hawaii where it continued training. The U.S. Navy had turned back a Japanese invasion of Midway Island in June 1942. The island’s location in the Northern Pacific was of strategic importance. As a result, combat units continued to defend the tiny patch of land. In December 1943, VMF 114 was shipped to Midway Island for three months. Then it was back to Oahu to prepare for shipment to Espiritu Santo, a staging area for the Americans’ advances against the Japanese. After additional flight and survival training. VMF 114 moved into its first combat area. Flying from the Green Island group near Papua New Guinea, the squadron suffered its first losses. The Japanese had created a huge base at Rabaul on the island of New Britain. By 1943 there were over 100,000 enemy stationed there. Although Rabaul would be ‘bypassed,’ American air and naval forces kept up unremitting attacks on it and on another enemy base at Kavieng. The Americans did not dare allow an exceeding well trained and increasingly desperate enemy any opportunity at disrupting our advances elsewhere. Weather, combat and air accidents resulted in VMF 114’s loss of nine pilots. The reality of war was now sinking in.

Over many beers during R&R in Sydney, Australia, the men designed their squadron’s new “Death Dealers” logo.

VMF 114 then was thrown into the maelstrom of the American landings in the Palau Islands.

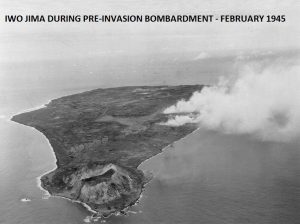

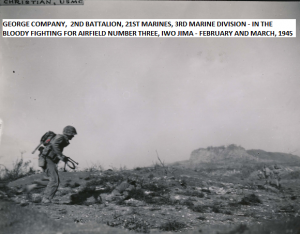

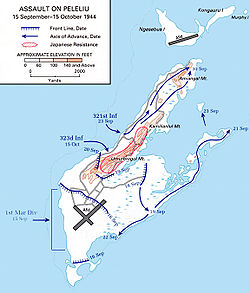

General Douglas MacArthur’s advance into the Philippine Islands in 1944 initially required that his eastern flank be protected. The Palau Islands, some 800 miles to the east had several islands that were heavily fortified, and a plan had been in place to attack and neutralize the Japanese there. However, the American landings in the Philippines were moving ahead of schedule. Certain U.S. commanders expressed extreme doubts as to the need to invade the Palau Islands insisting that, given the circumstances, they could be bypassed and isolated. However, invasion plans were already laid on, and the Marines’ 1st Division and Army regimental combat teams were tasked with taking the Palau group’s Peleliu Island. It would set in motion a horrific battle, which to this day is still cloaked with controversy. Echelons of VMF 114 began flying northward to provide close air support on 9 September 1944. Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Emirau, Pityiliu, and Owl Island were rest and refueling points enroute. After an inadequate pre-landing naval bombardment, young Americans hit Peleliu’s beaches on September 15, 1944. They immediately found themselves in a living hell.

General Douglas MacArthur’s advance into the Philippine Islands in 1944 initially required that his eastern flank be protected. The Palau Islands, some 800 miles to the east had several islands that were heavily fortified, and a plan had been in place to attack and neutralize the Japanese there. However, the American landings in the Philippines were moving ahead of schedule. Certain U.S. commanders expressed extreme doubts as to the need to invade the Palau Islands insisting that, given the circumstances, they could be bypassed and isolated. However, invasion plans were already laid on, and the Marines’ 1st Division and Army regimental combat teams were tasked with taking the Palau group’s Peleliu Island. It would set in motion a horrific battle, which to this day is still cloaked with controversy. Echelons of VMF 114 began flying northward to provide close air support on 9 September 1944. Guadalcanal, Bougainville, Emirau, Pityiliu, and Owl Island were rest and refueling points enroute. After an inadequate pre-landing naval bombardment, young Americans hit Peleliu’s beaches on September 15, 1944. They immediately found themselves in a living hell.

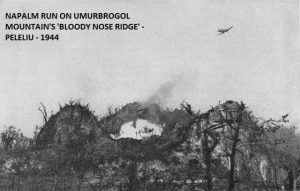

How does one begin to describe the protracted hell of Peleliu?  Consider this: Peleliu was defended by nearly 11,000 Japanese troops. The enemy had rethought how to confront Americans in island fighting, and no longer would expend its men on massive suicide attacks. The plan was to make the Americans pay for every inch taken. The Palaus had been in Japanese hands since the end of World War I. Peleliu’s six square miles held a defensive system where virtually every square yard was covered by interlocking fields of fire. The island’s mountain range, the Umurbrogol, contained over 500 natural and man-made caves, as well as the command center. All beaches were mined, with extensive anti-tank traps and obstacles. All caves were connected with tunnels, and heavy artillery was hidden behind sliding steel doors. Caves and defensive bunkers were virtually invisible, concealed behind rock and vegetation. The Japanese even had a miniature railroad to move some artillery from firing point to firing point.

Consider this: Peleliu was defended by nearly 11,000 Japanese troops. The enemy had rethought how to confront Americans in island fighting, and no longer would expend its men on massive suicide attacks. The plan was to make the Americans pay for every inch taken. The Palaus had been in Japanese hands since the end of World War I. Peleliu’s six square miles held a defensive system where virtually every square yard was covered by interlocking fields of fire. The island’s mountain range, the Umurbrogol, contained over 500 natural and man-made caves, as well as the command center. All beaches were mined, with extensive anti-tank traps and obstacles. All caves were connected with tunnels, and heavy artillery was hidden behind sliding steel doors. Caves and defensive bunkers were virtually invisible, concealed behind rock and vegetation. The Japanese even had a miniature railroad to move some artillery from firing point to firing point.

The Marine’s commander predicted the island would be taken in four days. It would take two months, and decimate the 1st Marine Division.

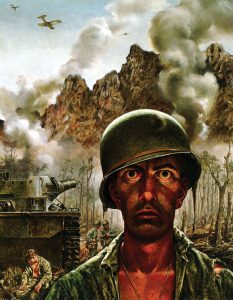

The squadron landed on Peleliu on September 26 (D+9) as the land battle raged less than two miles away. As Bud Daniel writes in A Cowboy Down: A WWII Marine Fighter Pilot’s Story: “All 24 Corsairs arrived in good shape. The howitzers were firing their large shells toward the caves on Bloody Nose Ridge. Marine infantry was busy fighting the ten thousand Japanese that were holed up in these caves. Peleliu looked to us like it was on a planet in another universe. Almost all of the trees had been blown to shred or splintered into pieces. The surface, nothing but coral rock, was also blown apart. We had been warned of snipers and we could hear large shells blasting, creating massive holes and generating lots of smoke. In the distance stretcher-bearers were trying to bring dead and wounded Marines down the coral precipices. It was a horrible battle and we were on the perimeter 1500 yards from the action. What I’m describing was continuous round the clock horror.” El Paso’s Tom Lea, an artist with Life magazine, was a changed man after witnessing Peleliu’s carnage. “The Two thousand Yard Stare,” is one of his most famous paintings. It captures a young Marine’s mental state as he prepares to go back into battle, after seeing many of his compatriots die:

The Two Thousand Yard Stare, by Tom Lea

The squadron’s pilots would load up with bombs or napalm, take off, often not even retracting their Corsairs’ landing gear, as some targets were fifteen seconds away. They would return to the airfield, reload, and fly another mission. For the next six months, VMF 114 labored tirelessly to support Marines and soldiers trying to root out the well-hidden and ferocious enemy. When time and circumstances allowed, “barge runs” were made in and around neighboring islands. Other Palau islands were also well defended. The carnage on Peleliu caused the U.S. to re-think invading most of them. But the Japanese on Koror, Babelthuap, Ngesebus, and Anguar were bombed and strafed continuously, to ensure no reinforcements would slip into Peleliu, and no aircraft could lift off. It was dangerous work for Bob’s squadron. The grind of battle, tension of close air support and enemy anti-aircraft artillery, long combat air patrols providing ‘cover’ for the invasion fleet, and stifling heat and humidity (Peleliu lies just seven degrees north of the equator), took its toll. Occasional beer runs to rear areas like Hollandia helped some, but not much. VFM 114 also flew long-range bombing missions – some as far as Yap Island, another enemy stronghold.

All the pilots suffered ‘gray-outs’ from the g-forces of dive bombing. Low flying attacks attracted flak, and on several occasions, Bob’s aircraft was holed by anti-aircraft shrapnel. On one occasion, Bob got shot up on a barge run over Babelthuap. Suddenly, his cockpit filled with smoke. American DUMBO aircraft (sea rescue float planes) were staged under air routes and pilots knew that if captured by the Japanese, they would be tortured and killed. Bob unbuckled his safety harness, threw back the cockpit canopy, and turned for friendly waters. As he prepared to bail out, the smoke cleared. He sat back down, hoping to make it home, It was a long thirty minutes of flying back to Peleliu, with Bob wondering when the engine would seize up. It didn’t. It turned out that shrapnel had struck his radio equipment. When his canopy was opened, the fire went out.

Others were not so lucky. The squadron’s revered commander, Major Robert “Cowboy” Stout died on March 4, 1945 on a strafing and bombing run over Koror. His death devastated the squadron.

The squadron rotated back to the United States in late March of 1945. Captain Peebles was then placed at Page Field, where he taught new pilots gunnery and rocketry at Parris Island. The war ended in August, and Bob was given a choice of staying in the military. His response was affirmative. The Marine Corps told him to go home, and he would be called in six months. As six months rolled around, he still hadn’t received his call back, so he decided he had better do something else with his life, so he re-enrolled at the University of Texas, and signed up to play football. Within a week, the Marine Corps called to invite him back into the service. “I was so sore from football practice,” he told me, “that I was never so happy to get a call in my life.”

Bob’s military career ‘took off’ after World War II. He married Adeline in Lockhart, Texas at the First Christian Church. They would have five children, Robert Jr., Bonnie, Sarah, Jo Leslie, and Patty.  Fortunately, Addie proved to be a wonderful military spouse, as the growing family would move with Bob to his various military assignments. In 1950, North Korea invaded the south. Captain (and later Major) Bob Peebles was shipped to Japan, and then to South Korea, and became the Executive Officer of a radar squadron. Then he returned to Cherry Point, N.C. The next years were fulfilling. As a major, he was appointed to the Joint Landing Force Board at Camp Lejeune, where future amphibious operations were studied. Then it was back to Korea in

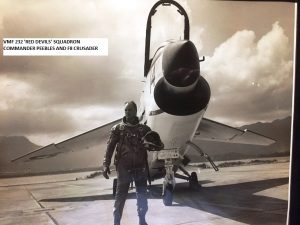

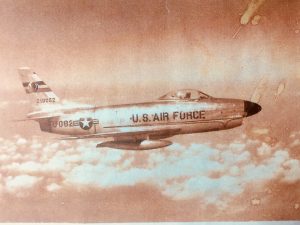

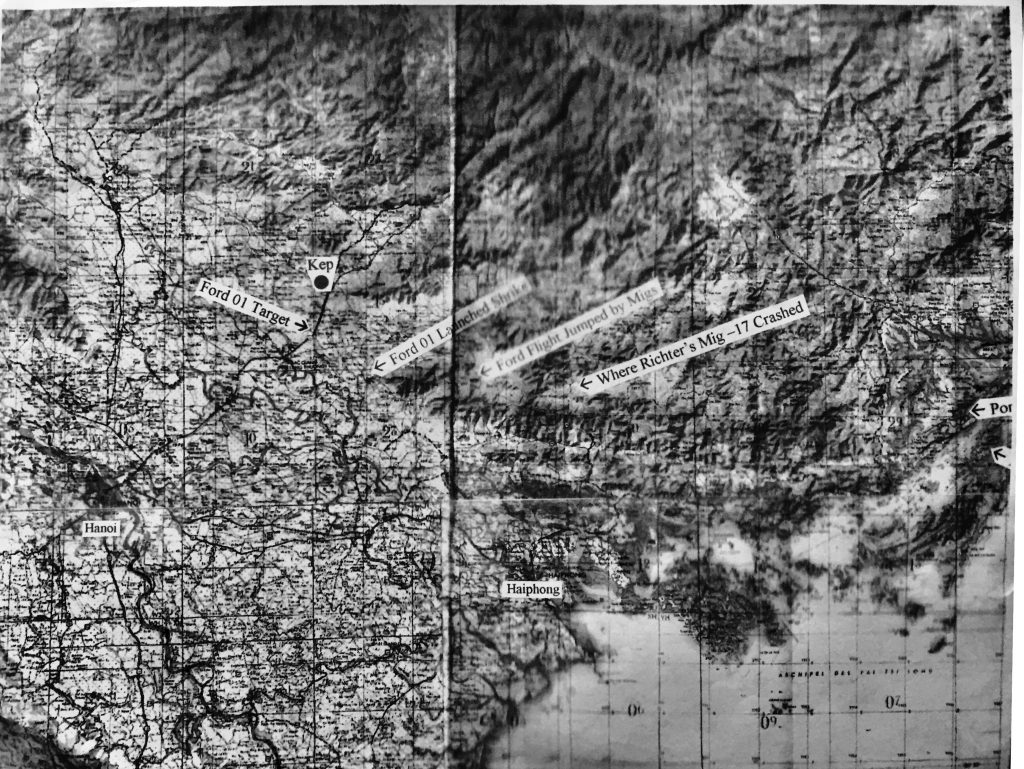

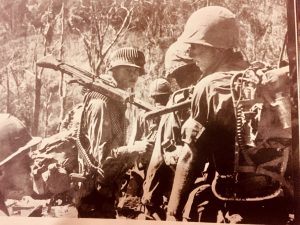

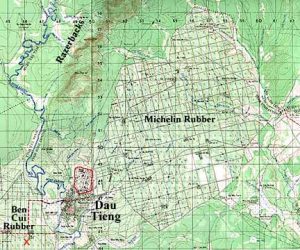

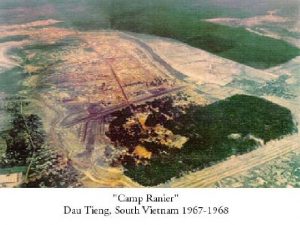

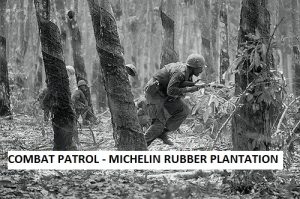

Fortunately, Addie proved to be a wonderful military spouse, as the growing family would move with Bob to his various military assignments. In 1950, North Korea invaded the south. Captain (and later Major) Bob Peebles was shipped to Japan, and then to South Korea, and became the Executive Officer of a radar squadron. Then he returned to Cherry Point, N.C. The next years were fulfilling. As a major, he was appointed to the Joint Landing Force Board at Camp Lejeune, where future amphibious operations were studied. Then it was back to Korea in  1954. Duty stations included Kaneohe Marine Air Station in Hawaii. In 1959, he became squadron commander of VMF 232, flying F8 Crusaders. In 1967, Colonel Peebles served in Viet Nam as air officer attached to amphibious operations.

1954. Duty stations included Kaneohe Marine Air Station in Hawaii. In 1959, he became squadron commander of VMF 232, flying F8 Crusaders. In 1967, Colonel Peebles served in Viet Nam as air officer attached to amphibious operations.

Bob retired in 1969, and in 1973 he and Addie moved to Caldwell County. They settled on some of the Strandtman land outside of Lockhart, living there until Addie passed away in 1999. Bob now lives in Bastrop with youngest daughter Patty. He is proud of his service to his country, but not one to brag.

The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded to someone who “distinguishes himself or herself by heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in an aerial flight.” He received that honor for airstrikes in the Rabaul, Kavieng, and Palau Islands areas during World War II. The Legion of Merit is awarded for “exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements.” He was honored with this award for service during the Vietnam conflict. When asked about his Bronze Star with V device, which is only awarded for combat heroism or for someone “exposed to personal hazard during direct participation in combat operations,” he only laughs and says, “I guess I got that for bravery.” The reality is more vivid: He was the acting commanding officer of a Ground Control Intercept unit near the North Korean port of Hungnam in December 1950. The Americans were in a fighting retreat from the Chosin Reservoir area in the bitter winter, as hordes of communist Chinese tried to surround them. Those who survived the near-debacle were evacuated through Hungnam, along with tens of thousands of Korean refugees. Captain Peebles evacuated the over two hundred men in his squadron on an LST just before the port facilities were destroyed as the enemy entered the area.

Destruction of Hungnam Harbor

Colonel Bob Peebles typifies the best of the “Greatest Generation.” If you see him, be sure to tell him thanks for his service to our country.