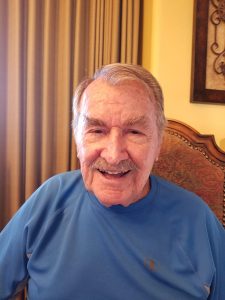

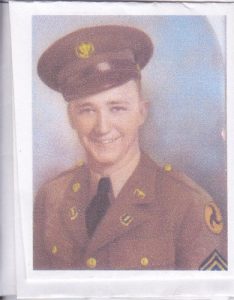

Austin C. Pittman favored me with two interviews over the last two years, and I finally am putting the wealth of information he provided me to good use. He is the oldest child of Lenford and Lillie (Harris) Pittman, both from long-time families in the Dale area. Austin had two younger brothers, Lonnie and Charles. Lenford Pittman had a variety of careers as Austin was growing up. Among other things, he ran a cotton gin and store for John Horner, and later owned and operated a dry goods and grocery store. In the early 1920s, he was a streetcar operator in the state capital. Austin was born there on November 13, 1922. The family lived most of Austin’s early life at 602 S. Commerce in Lockhart. Although raised as a Baptist, he became a member of the First Christian Church in 1939. He and Eleanor attend there today.

Like everyone else in the Depression, when he wasn’t attending school he was working. After graduating from Lockhart High School in 1941, the first year it went through the 12th instead of the 11th grade, he went to work full-time as an assistant manager of the A&P Grocery Store in Lockhart. Knowing he would be subject to the new peacetime military draft, and along with several of his classmates, Austin travelled to San Antonio, hoping to qualify for the Army Air Corps’ pilot training program. The Air Corps’ requirement was that a young man have two years or its equivalence in college to become an officer and pilot. Austin passed the equivalency tests, as well as the physical tests. In late 1941 he became an unpaid reservist in Uncle Sam’s Army Air Corps. Told he had to wait until there were training slots available, he returned to the grocery business. The Luling A&P store lost its manager, and at the ripe old age of 18, Austin became that store’s manager, riding his Cushman motor scooter to and from Lockhart every day.

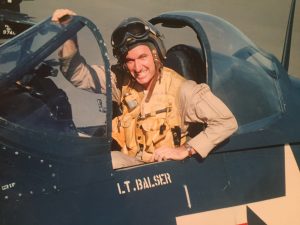

Austin received his orders to report for training on January 26, 1943. Another Lockhart man, Newton (“Doc”) Wilson, who would later become President of Lockhart State Bank, also received his orders that day. Reporting to San Antonio, he stood in formation when the commander of the training battalion told each of the new recruits, “Look to your left. Now look toward your right. Only one of you will be left and successfully finish flight training.” Austin was determined to be the one left. Because of the continuous ramping up of the war effort, aviation training was often backlogged. So, after brief (and somewhat brutal) basic training at Wichita Falls, Austin attended “Pre-pre flight training” on the campus of Kansas State Teachers College in Emporia. The local residents opened their homes to the young cadets, and Austin has fond memories of the Kansans’ kindnesses. Then it was off to El Reno, Oklahoma, for Basic Flight Training, then to Enid, Oklahoma for Primary on a Fairchild PT-19 “Cornell,” then to Altus, Oklahoma for Advanced. Austin was an “Altus Ace,” as they dubbed themselves. He received his commission as a 2nd Lieutenant and his wings in April, 1944. His mom and dad drove to Oklahoma to attend his graduation ceremonies.

Austin always wanted to fly a P-38 fighter. His second choice was to pilot a Martin B-26 “Marauder.” He got his second choice, and never regretted it. The B-26 was a ‘hot’ aircraft. High wing loading and a tricycle landing gear required faster than normal landing speeds. Early versions of the Marauder were dangerous in the hands of inexperienced pilots, earning it nicknames such as “Flying Coffin,” and “Flying Prostitute” (because it was so fast and had no visible means of support). Structural modifications, stronger engines, and better pilot training reduced training deaths, but it was no aircraft for a novice. Despite bad press, the Marauder was a highly effective mid-altitude bomber, and racked up impressive records in both Europe and the Pacific. Bombing accuracy was far better than the higher flying B-24s and B-17s.

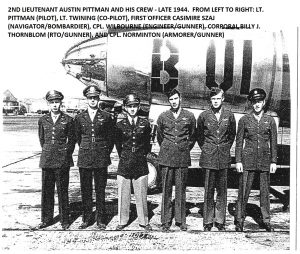

Austin transitioned into B-26s at Laughlin Army Airfield at Del Rio, Texas. At Barksdale Army Airfield, Louisiana he met and trained with his new crew. Each of the six men knew that their lives depended on working smoothly and efficiently.

By late 1944, the Army Air Force deemed 2nd Lieutenant Austin Pittman and his crew ready for combat. The next challenge was getting a B-26 and its crew from the United States to the European Theater, where they had been assigned to the 597th Bombardment Squadron, 397th Bombardment Group, Ninth Air Force. It was not an easy process. Austin and his co-pilot flew to Baltimore to pick up a new aircraft, then to Savannah, Georgia and on to Morison Field at Palm Beach, Florida where they picked up a celestial navigator. In the meantime, the remaining four crew members crossed the Atlantic Ocean by ship.

There were two main routes from the U.S. to the European Theater. Both were fraught with danger. The Northern Route, through Greenland and Iceland, had been closed to twin-engine aircraft since late 1942 because of high number of losses (and disappearances) due to bad weather.  The Southern Route, through South America, was somewhat safer, but not by much. Six B-26s were send south on December 13, 1944. While not flying in formation, they were following the same route. First stop: Puerto Rico. Then it was on to British Guiana and then down to Belem, Brazil. Somewhere over Brazil, two of the six aircraft went down in the jungles, and the planes and crews were lost. Austin’s most vivid memory of the flight was the enormity of the Amazon River. After refueling in Natal, Brazil, Austin piloted his aircraft toward a speck of land called Ascension Island, in the middle of the South Atlantic. Finding the three by five mile volcanic island by primitive radio direction finders gave everyone reason for re-affirming their religious beliefs. After successfully landing at “Wideawake Airfield,” it was on to Roberts Field in Monrovia, Liberia. Then up the west coast of Africa to Dakar and Marrakech, Morocco. Winter storms kept them grounded in Morocco for over a week. In the meantime, other aircraft stacked up there awaiting clearance for England. Finally, two days before Christmas 1944, huge numbers of aircraft were released toward England. The result was, to put it gently, was ‘interesting.’ Slower aircraft had been sent out first, with faster planes staggered out later. They all appeared over the socked-in island at the same time. Unable to find the ground, Austin’s B-26 gingerly descended into the clouds, popping out nearly at building level. Because of air traffic, he had to take the plane out to sea and approach again, trying to land. After three tries, and about out of fuel, he dodged church steeples to land safely in England on Christmas Eve, 1944. It had taken the air crew eleven days to fly from the U.S. to England!

The Southern Route, through South America, was somewhat safer, but not by much. Six B-26s were send south on December 13, 1944. While not flying in formation, they were following the same route. First stop: Puerto Rico. Then it was on to British Guiana and then down to Belem, Brazil. Somewhere over Brazil, two of the six aircraft went down in the jungles, and the planes and crews were lost. Austin’s most vivid memory of the flight was the enormity of the Amazon River. After refueling in Natal, Brazil, Austin piloted his aircraft toward a speck of land called Ascension Island, in the middle of the South Atlantic. Finding the three by five mile volcanic island by primitive radio direction finders gave everyone reason for re-affirming their religious beliefs. After successfully landing at “Wideawake Airfield,” it was on to Roberts Field in Monrovia, Liberia. Then up the west coast of Africa to Dakar and Marrakech, Morocco. Winter storms kept them grounded in Morocco for over a week. In the meantime, other aircraft stacked up there awaiting clearance for England. Finally, two days before Christmas 1944, huge numbers of aircraft were released toward England. The result was, to put it gently, was ‘interesting.’ Slower aircraft had been sent out first, with faster planes staggered out later. They all appeared over the socked-in island at the same time. Unable to find the ground, Austin’s B-26 gingerly descended into the clouds, popping out nearly at building level. Because of air traffic, he had to take the plane out to sea and approach again, trying to land. After three tries, and about out of fuel, he dodged church steeples to land safely in England on Christmas Eve, 1944. It had taken the air crew eleven days to fly from the U.S. to England!

The B-26 crewmen who arrived in England by ship were aware that two B-26s had been lost in the jungles of Brazil. Because of the weather delay in Morocco, the four were not even sure that they would see their pilot and co-pilot again. They were pleasantly relieved with Lieutenants Pittman’s and Twining’s re-appearance.

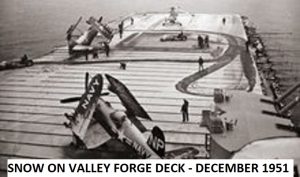

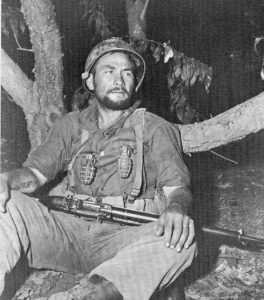

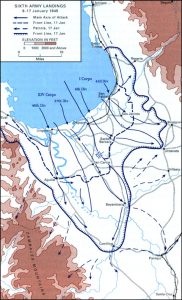

Almost immediately after settling in, the Pittman crew and their aircraft was moved, along with most of the other 597th, to forward bases in northern France. He would fly from there and after its capture, from Venlo, Holland. Over the next four months, Austin flew twenty-two bombing missions against the enemy. Many missions were against rail yards and ammunition dumps. Some were in close support of advancing Allied troops, entangled in combat with Germans defending the Fatherland. German fighter aircraft had all but disappeared, but anti-aircraft flak could and did take a heavy toll, especially since B-26s flew at lower altitudes. Combat formations included on aircraft that discharged ‘chaff’ –aluminum strips – to confuse enemy radar. Some times it worked. Some times it didn’t. The Marauder could take punishment. After one mission, Austin counted 123 holes from anti-aircraft shrapnel in his aircraft! No one was injured, and the plane was patched up and flew again. Austin has vivid memories of two “very good days.” The first was when he was part of a mission tasked with finding and destroying a huge enemy ammunition dump near the Swiss border. Carefully avoiding neutral airspace, he and his crew unloaded their ordnance on what they suspected was the target. All hell broke loose. They had destroyed the target! Elated, he buzzed the mess hall. The Inspector General was present and was not impressed, and Austin received a small fine. A small price to pay for a highly successful mission. Austin was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for this mission.

Another instance was more mundane. His B-26 took off in formation for a mission. Upon the formation’s return the control tower had every aircraft lower its landing gear, as one had left a tire on the runway on takeoff. Sure enough, 1st Lieutenant Pittman’s plane had a shredded tire. Approaching gingerly, Austin and his co-pilot made a perfect landing, wheels down.

As the Allies advanced into Germany, airfields were quickly constructed. First priority were the runways. Housing was primitive. The men lived in tents, slept on cots, and endured miserable winter weather as best they could. Horrible weather, typical of northern Europe, and required down-time allowed aviators and crews time for some leisure activities. Austin’s sideline was playing bridge for money. And he was good at it. Sending his winnings home, he compiled a nice nest egg.

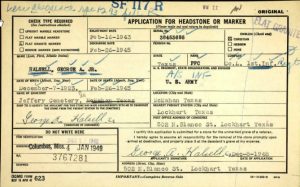

One of the saddest incidents that Austin endured was the death of two of his crewmen. On April 19, 1945, Austin was not scheduled to fly. Billy Thornblom, his RTO, and Casimir Sjaz, his bombardier, were assigned to another aircraft for a combat mission. At 4:06 p.m. a B-26G, aircraft # 43-34450, piloted by 1st Lt. Elmer Frank, took off from a field at Perrone, France. It was loaded with bombs. The pilot apparently lifted off too suddenly, not using the full runway, and pulled up into a stall. Trying to recover, the aircraft was hit with prop wash from other bombers. The Marauder ‘mushed’ downward and pancaked 100 feet from the end of the runway, bursting into flames. Sjaz was killed in the crash. Thornblom and one other crewman escaped, but Thornblom was grievously burned. Austin was able to visit him in the hospital before he died on April 26, 1945.

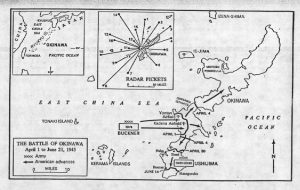

Austin’s 22nd mission was on the morning the war ended in Europe. That afternoon, he had loaded with bombs for his 23rd  when he was told the war was over. Because he had over 20 missions he was given the choice of transferring to the Pacific Theater, or coming home. He chose to go home. However, before he could do that, he and his aircraft participated in a huge victory celebration fly-over at Paris. He felt that getting all those aircraft where they were supposed to be was as dangerous as a mission over enemy territory. Sadly, his beloved B-26 was relegated to a mothball fleet, somewhere in France, and probably scrapped.

when he was told the war was over. Because he had over 20 missions he was given the choice of transferring to the Pacific Theater, or coming home. He chose to go home. However, before he could do that, he and his aircraft participated in a huge victory celebration fly-over at Paris. He felt that getting all those aircraft where they were supposed to be was as dangerous as a mission over enemy territory. Sadly, his beloved B-26 was relegated to a mothball fleet, somewhere in France, and probably scrapped.

Loaded on a ship, Austin came home. He says that re-adjustment to civilian life came easy. He went back into business with his father and brother Lonnie, selling dry goods and groceries. Deciding to leave the family business, Austin moved to Port Lavaca where he met and married Eleanor Paul, the love of his life, in 1952. Austin owned and operated grocery stores in Lake Jackson, Angleton, and Bay City. He sold his stores and returned to Lockhart in 1967, settling on land he had purchased in the 1950s.

Eleanor heard something in the hairdresser’s (where else in a small town?) about the owner of the White’s Auto Store wanting to sell. So, almost immediately, Austin “un-retired” and successfully operated that store (and was a Cushman dealer also) until selling out in 1980. When he and Eleanor returned to Caldwell County, they found that they couldn’t drill a successful water well on their property. The solution – create a water supply corporation to that for those in the area. Austin is still chairman of the board of the Polonia Water Supply Corporation, which provides safe water to many customers north of Lockhart.

Austin Pittman attends American Legion meetings regularly. He and Eleanor remain active members of First Christian Church. He will tell you that his has been a wonderful life. While rightfully proud of his role as an aviator in World War II, his proudest achievement is being the husband to Eleanor, and the father to six fine children – Paul, Martha (Sanders), David, Mary (Voigt), Gary, and Austin.

Next time you see him, remember that he is part of the Greatest Generation, and thank him for his service to our wonderful country.