THE ALEUTIAN CAMPAIGN

THE ALEUTIAN CAMPAIGN

PART ONE

By Todd Blomerth

(These three articles were published in the Lockhart Post Register and the Luling Newsboy Signal in August/September 2011)

If you haven’t noticed, I love military history. And I have a great interest in World War II, what led up to it, and how we as Americans, with our Allies, were able to overcome two truly evil empires bent on world domination. D-Day, Guadalcanal, the Battle of the Bulge and Iwo Jima are familiar places or events in the lives of the Greatest Generation. I am about to tell the tale of one of the more obscure episodes in World War II, and one that is still not very well understood by many people – the series of sea and air actions, and island landings that happened on American soil in the Territory of Alaska. And believe it or not, this little known campaign in one of the most hostile climates in the world was decisive in the outcome of the United States’ war with the Japanese Empire.

In 1941, Alaska was about as remote a location as you could find. The US had acquired Alaska in 1867 from the Russian Empire for 7.2 million dollars, or about two cents an acre. Even so, Secretary of State William Seward, who negotiated the purchase, was publicly blasted by some for wasting taxpayers’ money on a chunk of frozen land. Apart from Inuit, Aleut, and other indigenous peoples, the only people living in this vast piece of real estate two and half times larger than Texas were a few Russian settlers, trappers, hunters, commercial fishermen, and loggers. Alaska was only ‘discovered’ by most Americans in 1896 when the Klondike Gold Rush brought hordes of gold seekers flocking to the southern end of the territory in search of riches.. When the gold played out, so did the interest in Alaska, and the territory once again reverted to a state of quiet isolation.

After the Japanese humiliated the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War a few years later, many American military planners realized that sooner or later, the United States might end up fighting a war with the militaristic Japanese Empire. With that in mind, Alaska’s strategic importance began to be seen by the US military. In 1935, General Billy Mitchell, the leading military aviation pioneer of his time, told Congress, “I believe that in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world. I think it is the most important strategic place in the world.” To the Americans, the islands appeared as possible jumping off points for Japanese attacks on the American West Coast. Alaska was closer to Japan than New York. If the Japanese took Hawaii, its forces would still be 2,400 miles from the U.S. mainland. If Alaska was conquered, bombers could reach Seattle and its huge Boeing plant in three hours.

The Japanese were not unmindful of Alaska’s importance either. Stretching 1,200 miles from the western end of the Alaskan Peninsula, the Aleutian Islands represented potentially valuable real estate to Japan. It too was aware of the islands’ value as bases to attack the heart of the United States. Likewise, the Empire knew that in the event of a war the Americans could use the islands as a staging point against their Kurile and home islands.

Both sides had a stake in controlling shipping and air lanes between American and Russian Asia as well. When America’s massive Lend Lease assistance to the Soviet Union required shipping of aircraft and other war supplies through Siberia, this would become even more apparent.

Supplying remote outposts was nothing new to the Japanese. The Japanese had been fighting in China and Manchuria since 1931. But once Japan ensured that the Soviet Union would not attack it or its conquered territory in Manchuria, it had turned most of its military attention southward, toward the oil and resource rich lands of Southern Asia. American planners were caught flat footed by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Wake Island, and the Philippines, and were scrambling to assemble its armed forces to respond to the seemingly invincible Japanese war machine. Lying between 51 degrees and 55 degrees in latitude, the thinly populated Aleutian chain would be very hard to defend. The islands’ distance from the Alaskan mainland was a serious challenge. There were no highways into the area. To get there from the US contiguous states, you either flew (a risky proposition) or took a steamship. In the late 1920s, President Herbert Hoover had ordered a study of the feasibility of constructing of a road from the Lower 48 States into Alaska, but the plan was shelved because of the high cost, and a route was never even surveyed (The famous Al Can Highway, built primarily by African American service troops, wasn’t completed until late in 1942). And once ‘in’ Alaska, you were still perhaps a thousand miles or more from your ultimate destination on Attu or Kiska or one of the other islands. Attu, the further west of the island chain, was in the Eastern Hemisphere and five time zones back from the Alaska territory’s capital at Juneau! Imagine the distance from Atlanta to San Diego and you get some idea of the distances involved.

The 1,200 Miles of the Aleutian Island Chain Were Misery For The Troops Assigned There For Both Sides

Weather conditions were also particularly harsh. The Japan Current moved up from the south where it slammed into dry, cold air from Siberia. It made for ice free oceans, but also for some of the worst weather in the world. 140 mile an hour gales were common. Fog was omnipresent. There were as few as 10 clear days in a year on many of the Aleutian Islands. Pilots dealt with ceilings that went from 500 feet to zero in a matter of minutes. Cold and wet weather was made worse by howling winds that blew down tents, flipped over airplanes, and made men go mad. An Air Force historian noted that, “oil becomes like jelly, hydraulic systems freeze, and rubber becomes brittle and fractures” under such conditions.

And there were more problems still. The frigid Alaskan soil could not sustain enough agriculture to support a large number of troops. Everything would have to be shipped from the Lower 48, but resupply ships only arrived intermittently. America was scrambling to build the infrastructure to fight a two front war, and supplying England and the Soviet Union with enough materiel aid to keep them from collapsing from the German onslaught. And those ships that did sail had few radio homing devices or radar to assist in navigation, and relied on highly inaccurate sea charts that the Russians had assembled in 1864. Aviators assigned to the territory had to use Rand McNally road maps. There were no highways of any consequence in the entirety of the Alaskan mainland – even between Anchorage and Fairbanks, the two largest ‘cities.’ Bush pilots landed on glaciers, ice or if equipped with floats, in rivers and lakes. Airfields were almost non-existent. There were none in the Aleutians. There were no trees because winds prevented them from taking root. Beneath everything lay the muskeg – “a thin elastic crust of matted dead grasses something like celery, overlying a topsoil of dark volcanic ash which became quicksand whenever it was wet, which was to say all the time.”

Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr.

In June of 1940, Colonel Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. was assigned by Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall to command a newly created Alaskan Defense Command. The hard-bitten, plain speaking son of Confederate general, Buckner had graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point in 1908. He was a flight instructor during World War I. In the 1930s he was an instructor at West Point, where he earned the reputation as a hard task master. Although controversial, his leadership would eventually assure the United States’ mastery of the region.

(Next – Creating something from nothing, interservice rivalry, and the bombing of Dutch Harbor).

PART TWO

“This Was Nobody’s Favorite War”

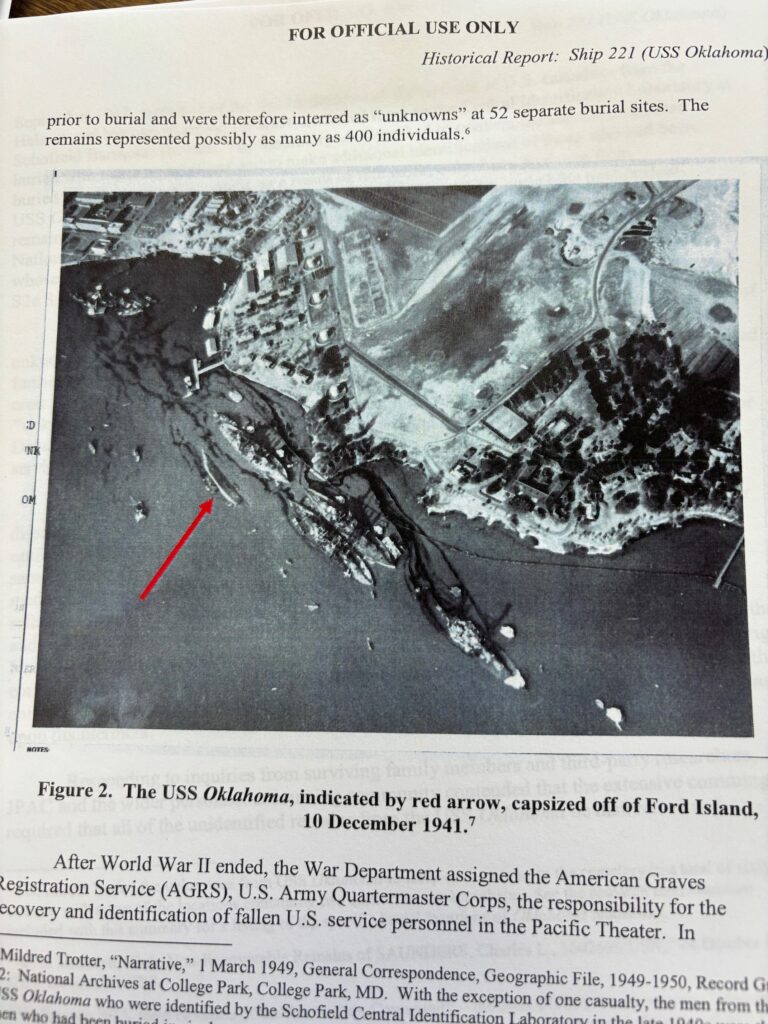

The attack on Pearl Harbor devastated the American Pacific Fleet. Other attacks against American military installations in the Philippines and elsewhere in the Pacific severely limited the US’ ability to strike back at the Japanese Empire. A devastating first strike was a crucial element of Japan’s war strategy. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Japan’s foremost naval strategist, had travelled extensively in America in the 1920s. He knew America’s industrial and military potential and realized that war would wake a ‘slumbering giant’ that would eventually overwhelm Japan with its superior productive capacity. Yamamoto felt that Japan’s only route to victory lay through crushing America’s will to fight by completely destroying the US Pacific Fleet and then quickly negotiating a favorable peace. However, due to a stroke of luck, none of the fleet’s priceless aircraft carriers had been at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Realizing that an attack and occupation of at least some of the Aleutian chain would provoke an American response that would given Japan another opportunity to destroy America’s precious aircraft carriers, Yamamoto ordered landings on Attu and Kiska, two of the furthest western islands in the chain, as well as an air assault on bases in and around Dutch Harbor on Umnak and Unalaska. Dutch Harbor Naval Base and Fort Mears were the main fortified naval and army bases in the Aleutians, and also served a supply points for the remainder of American forces in the area. By mid-1942, and through sheer force of will, newly promoted Alaskan theater commander, General Simon Bolivar Buckner had substantially improved Alaska’s defenses. But this improvement was relative. There were still only 45,000 soldiers to defend all of Alaska, and almost all were on the mainland, with only around 13,000 personnel at Dutch Harbor and the newly constructed airfield at Fort Glenn on nearby Umnak Island. And many of these men were in construction rather than combat units. The only other military presence in the Aleutians was a few weather stations.

USS Louisville – A Cruiser in the Small American Fleet

The US Navy was supposed to provide a defensive perimeter for Dutch Harbor to compensate for its light ground defenses, but the Navy was hampered by a lack of modern warships, which had to cover an enormous area – often without radar. A few older cruisers, destroyers, and obsolete S class submarines were assigned to the theater under Rear Admiral Robert Theobald, who was given the impossible task of establishing an airtight naval perimeter around the islands.

Further complicating matters, command authority in the North Pacific Area was divided and cumbersome. Upon reaching Alaska, Theobald became commander of the naval and air forces, while authority over the ground forces remained with Buckner. The two were ordered to operate a joint command with “mutual cooperation,” but they answered to different bosses and did not get along with each other.

Under Theobald was General William Butler, the commander of the Eleventh Air Force. His tiny air force consisted of a few obsolescent fighters and badly equipped B-17s and B-24s, as well as a number of PBY Catalina flying boats. One of the unit’s few bright spots was Colonel William O. “Eric” Eareckson, an incredible aviator and fearless maverick, who often became a one-man war against the Japanese. When not taking extraordinary chances with the enemy and weather, he instilled rigorous training and tactics. He was held in awe by his young aviators. His efforts also kept many of them alive in an environment where over two-thirds of aircraft losses were due to weather –not to the enemy.

To destroy the US will to fight in the Pacific, Yamamoto devised a complex strategy. Part of his forces would overrun several of the Aleutian Islands and attack the US base at Dutch Harbor. This would dilute American strength in and around Midway, and allow the Japanese, with their superior naval strength, to destroy America’s remaining carriers, and also occupy the strategically important island. The Alaskan portion of his plan was criticized by some as a dilution of the forces needed to win the all-important battle against the American fleet around Midway. The debate continued until Jimmy Doolittle and his squadron of B-25 bombers achieved a stunning surprise attack against Tokyo in early 1942 by launching off the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet after sneaking to within striking distance of the Japanese capital. The attack caused little damage to Japan, but the psychological impact was huge. The Japanese did not know how the bombers got to Japan but many assumed that they may have come from secret airbases in the Aleutians. Fear of additional attacks against the Home Islands led to the quick approval of Yamamoto’s invasion plan. On May 5, 1942, the Japanese Navy Order Eighteen authorized an invasion and occupation of the Aleutians. The Aleutian operation would go forward, siphoning many ships north, including the aircraft carriers Junyo and Ryujo that might have otherwise later turned the tide at the Battle of Midway.

The first phase of the invasion involved a surprise air strike against the islands. However, the Japanese would find American air defenses to be stronger than they had anticipated for several reasons.

In late 1941, Buckner began to secretly use funds earmarked for other purposes to build airbases at Dutch Harbor and on other Aleutian Islands. Buckner hand picked engineers to build airfields in the awfulness of the muskeg and sent them construction supplies in crates labeled as “fishery equipment.” Construction was possible only using experimental Marston steel landing mats. Japanese intelligence had no way of discovering these airfields since Buckner’s superiors were equally in the dark. Reliance on long-range I class submarines for visual reconnaissance of the defenses was a poor substitute for good aerial reconnaissance and spies – and the Japanese had none of those resources in the area. Then, on May 15th, the Americans partially broke the Japanese naval code. Intercepts revealed the Japanese invasion plan and the timing of the first attack against Dutch Harbor. American aircraft patrols were stepped up as a result, and spotted the Japanese fleet far at sea. The Americans around Dutch Harbor were ready. Anti-aircraft crews, largely made up of National Guard units from the lower 48 state, were well trained. At 0540 on June 3, 1942 radar picked up incoming aircraft launched from the Japanese aircraft carriers. A few minutes later, anti-aircraft guns opened up as Japanese fighters strafed the airfield and Japanese bombers released their lethal loads from 9000 feet. But the actual damage done was very small. Men were killed when a barracks was hit, but for the most part, the US forward facilities were left undamaged. The Japanese returned the following day, with much the same results. Some aircraft were caught on the ground, one ship badly damaged, fuel depots set afire, and a small number of soldiers killed. The weather proved to be an intractable foe–the Japanese could not see what they were bombing. Fog prevented American defenders from seeing incoming Japanese planes but also kept pilots from seeing their targets. Sometimes visibility was so poor that planes could not take off at all. The initial assault was postponed for several hours to allow for “better” weather, when pilots could at least see the end of the carrier deck. Cloud cover and fog made accuracy impossible. The second attack saw more breaks in cloud cover, but weather still played a huge factor.

Bad weather also hampered the American defenders. The US fleet trying to prevent the attack groped around in fog four hundred miles south of the enemy fleet, never making contact with the attackers. The weather allowed the Japanese fleet to escape undetected and unharmed. Airplanes were lost or damaged, but primarily as a result of howling winds and horrible visibility. As Brian Garfield noted in his book The Thousand Mile War, “It was not Japanese cleverness, and not American blundering, that kept the opposing forces from joining in battle; it was the power of Aleutian nature.”

There was one unexpected consequence of the attack. Pilot Tadayashi Koga shot down an American PBY patrol boat and in the process received damage to his A6M “Zero”, Japan’s nimble and fast fighter. He crash landed on nearby Akutan Island, and was killed. But his aircraft was virtually undamaged. It was found by American forces some weeks later, recovered, taken apart and studied. The knowledge learned about the aircraft proved invaluable in designing aircraft that would come to outperform the Zero.

Defending Dutch Harbor

Japanese Bombing of Dutch Harbor

.

The Occupation of Attu and Kiska

In the Central Pacific, the Japanese suffered a stunning defeat at Midway. Over 3000 Japanese sailors and aviators were killed and several of Japan’s most powerful aircraft carriers were sunk. Japan’s knock-out blow against the American fleet had backfired. It was a bitter pill to swallow for the proud Yamamoto. With his defeat at Midway, Yamamoto felt that any further effort in the Aleutians was a waste of time. He was convinced otherwise by his staff, which urged him to continue with the occupation of at least some of the island chain The American fleet was looking for the Japanese in the Bering Sea when a Japanese landing force hit the beaches on Kiska, and 350 miles further west, on Attu at 0120 hrs on June 7, 1942. The only defenders were ten men at a weather station who were captured fairly quickly. A few hours later, the Kiska landing occurred, again with no opposition.

Chichagof Harbor – Attu, Before the Attack

The Captured Weather Detachment on Kiska-The Men

Would Spend the Rest of the War in Japanese Prison Camps

Headquarters initially intended for the invaders to advance up the island chain, eventually attacking the Alaskan mainland. In the US, the Aleutian attacks and landings focused the attention of all branches of the military. Newly arrived aviators wanted to show that air power could effect Japanese submission; the Army wanted to show it had the combat skills to hurl the Japanese off American soil; the Navy was embarrassed because of its total failure to locate and destroy the Japanese fleet and prevent the invasions; and President Roosevelt was embarrassed by the occupation of American soil. Suddenly Alaska was on the minds of everyone in the command structure – and there was an immediate influx of men and materiel to counter the invasion.

The Japanese initially planned to evacuate Attu and Kiska in late 1942. It was later decided by the Japanese that they would stay indefinitely. “There is considerable conjecture [wrote one officer] about the Japanese need for such a God-forsaken hole. The general consensus seems to be that they need a submarine operating base…from which easy raids on our lend-lease shipping to the USSR can be carried out.”

It would take 10 months for the Americans to build enough strength to attempt ousting the invaders, and in that period, the number of men in the Alaskan theater grew to over 300,000. Increasing naval strength choked the flow of provisions to the invaders, making their lives increasingly unpleasant. In August of 1942, the American counterattack begin with an unopposed landing on Adak, 400 miles west of Dutch Harbor and within bombing range of Kiska and Attu Airbases continued to be built, in horrific conditions. The Japanese defenders received little additional support meanwhile due to the decline of Japanese military fortunes elsewhere. Bombing raids and reconnaissance missions over Attu and Kiska grew in size and accuracy. “For the next six months [writes Garfield] this was the strategy of the Aleutian Campaign: a nerve-racking, corrosive harassment of the enemy on Kiska.”

Believing Attu to be untenable, the Japanese commander evacuated the island’s defenders to Kiska in December of 1942. When an expected attack didn’t occur, the island was re-occupied by over 2500 men. Had the Americans been more alert, they could have occupied the island without firing a shot. Because of the lack of vigilance, horrific weather, and bad communications, as well as a change in the Japanese naval code that limited the code breakers’ best attempts, the Americans missed a huge opportunity. It would cost them dearly.

NEXT – The Retaking of Attu and Kiska, and a Postscript.

PART THREE

“The Theater of Military Frustration”

Famed naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison’s description of the Aleutian Campaign as “The theater of military frustration” is about as apt as any phrase can be. For both the Americans and Japanese, the remainder of 1942 and early 1943 was a period of feints and jabs, none with any knockout force, often totally missing the mark because of the horrific weather and unforgiving seas. The frustration engendered by protracted inactivity was demoralizing to both sides. American sailors and soldiers had cause to wonder why they were not fighting in a more active theater. For the Japanese, there was the inevitable sense of being left to their doom as higher-ups dealt with more pressing matters elsewhere.

The end of the Japanese occupation of American soil was slow in coming. In August 1942, an American force landed on Adak, four hundred miles west of any US base and 250 miles from Kiska. The Japanese were caught by surprise. In fact, American engineers and Seabees constructed an entire airfield with auxiliary buildings before the Japanese even knew they were there. Kiska started experiencing regular attacks from US bombers – and because of the limited number of pilots and the miserable weather, the Japanese couldn’t figure out how the Americans were able to step up their bombing campaign, which began causing greater damage and more deaths. By the time they finally found the new airbase, they had so few serviceable aircraft left that the Japanese could do nothing about it.

Because of setbacks elsewhere, Japan’s military resources and men were stretched thin – there would be little help for their forces in the Aleutians. Besides, the Japanese plan called for an evacuation during the winter anyway. Sensing the Americans would not occupy Attu, the Japanese evacuated its garrison to Sitka to concentrate their forces. The anticipated attack on Sitka never happened, but the Americans occupied several other smaller islands in the chain. After the Sitka evacuation, the Japanese high command re-assessed the strategic importance of the Aleutian Islands – perhaps the Americans could attack Japan from the north after all. The Japanese quietly reoccupied Attu. Sitka’s fortifications were strengthened. Evacuation plans were scrubbed by October 1942 and instead decided to expand their presence in the islands by occupying more of the Aleutian chain. However, by this point further invasions were no longer possible because of American air superiority. In early December, a convoy of troops sent to make new landings was diverted to the relative safety of Kiska instead.

The tide was turning decisively against the Japanese – by the end of 1942, there were over 150,000 US troops in Alaska, and Dutch Harbor was handing nearly 400,000 tons of shipping a month. Alaskan oil and coal production boomed. And in November the 1671 mile wonder called the Al-Can Highway was completed. The Lend-Lease route to the Soviets through Siberia was opened for business. But pressing series of major campaigns being waged against the Axis powers elsewhere meant that plans to kick the Japanese out of the Aleutians took a back seat to operations in the South Pacific and in North Africa. As always, the weather discouraged offensive operations as well, and the winter of 1942-43 was another horrific reminder of the nightmare involved in trying to carry out any major operation. In Fairbanks, -67 degree weather meant that aircraft engines had to be thawed out with blow torches! Fighters landing in the fog at Adak crashed into parked B-24s. Boats capsized. Hospital and mess tents were destroyed. The mostly Mexican-American Texans of the 176th Engineers– who had never even seen snow before – were continually blown off their feet by sudden winds called williwaws as they tried to complete the facilities at Adak.

General Buckner’s antipathy toward Admiral Theobald and his perceived reluctance to risk his few ships to the weather or Japanese finally came to a head. On January 4th, Buckner’s hostility contributed to Theobald’s replacement by Rear Admiral Thomas Kinkaid. Kinkaid and Buckner were kindred spirits who shared an offensive mindset – the inter-service rivalries died, and morale improved. There was a sense that there was some purpose in living in the frozen hell of the Aleutians – to kill Japanese. Kinkaid’s arrival marked the start of a new aggressiveness. On January 5, 1943, Americans landed unopposed on Amchitka, a mere 40 miles from Sitka. By January 28th, a new airfield had been completed there. Kiska became the object of sometimes hourly bombing raids.

General Hidichiro Higuchi, commander of Japan’s North Pacific ground forces, demanded additional reinforcements and naval cooperation to stop the American advances. The Japanese navy demurred, and instead of sinking American tonnage, used its submarines to bring supplies to other island outposts. With woefully inadequate equipment and suffering round-the-clock bombing, Higuchi’s men could never finish airfields on either Kiska or Attu. The Japanese defenders’ last hope for relief vanished on February 5, 1943 when Higuchi was instructed to ‘hold the western Aleutians at all costs’ with his available force. Slim chance – he had 8000 troops on Kiska and 1000 on Attu, and none were first-line troops. He possessed no artillery other than mortars. He had no tanks.

Meanwhile, Kinkaid created an effective blockade intent on starving the Japanese garrisons. More and more, supply convoys were either sunk or driven back. By early March 1943, the American air forces had sunk over forty Japanese ships. The stranglehold by the Americans was tightening. In response, the Japanese tried a desperate gambit that led to what became known as the Battle of the Komandorski Islands. A convoy of troops and supplies escorted by eight cruisers attempted to run the American naval gauntlet. If successful, the Japanese perhaps could hold Attu and Kiska and even mount and offensive against Kinkaid’s forces. In the ensuing battle, the blockading American fleet was outnumbered two to one. The flagship Salt Lake City, an older cruiser, was heavily damaged in a running daylight battle. Gutsy American destroyers, in an attempt to protect it, made a suicide charge with torpedoes against the Japanese cruisers – and the Japanese withdrew! Afraid that American aircraft would soon be approaching to assist, the last supply fleet turned back. “Admiral Kinkaid’s ridiculous little blockade [wrote Brian Garfield in The Thousand Mile War] had achieved complete success: [it] ended Japanese navy supremacy in the North Pacific and brought the end of the Aleutian Campaign in sight.”

Now it was time to bring combat troops for the invasion of the two islands. The first to be hit would be Attu. If Attu fell, Kiska would hopefully wither on the vine. Common sense would have suggested assembling a large unit trained in cold weather combat and amphibious landings, but common sense did not prevail. Ground troops under Buckner’s command were scattered all over Alaska. None were of division strength. Instead, the 7th Mechanized Infantry Division was transferred from scheduled service in the North Africa Theater. There was one small problem – it was training in southern California for desert warfare. With no training in cold weather warfare, and with little or no appropriate clothing or equipment, the division was sent north in April 1943. Its men were predominantly Hispanics, Mormons, Indians, and cowboys from Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Texas. It had absolutely no amphibious training. The lunacy of the division’s selection was compounded by a timeline that gave it only three months to prepare until the landing on Attu.

American intelligence said there were only 500 Japanese troops on Attu (its forces had been reinforced actually numbered over 2500). The Alaskan command told the 7th Division’s commander, Major General Albert Brown, that a single regiment could take the island in three days. Brown responded that suggestion was nuts – the island’s terrain alone would require a full week just to cross it. His pessimism was dismissed.

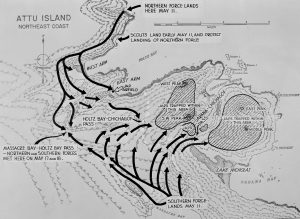

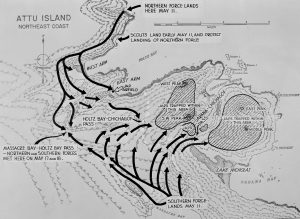

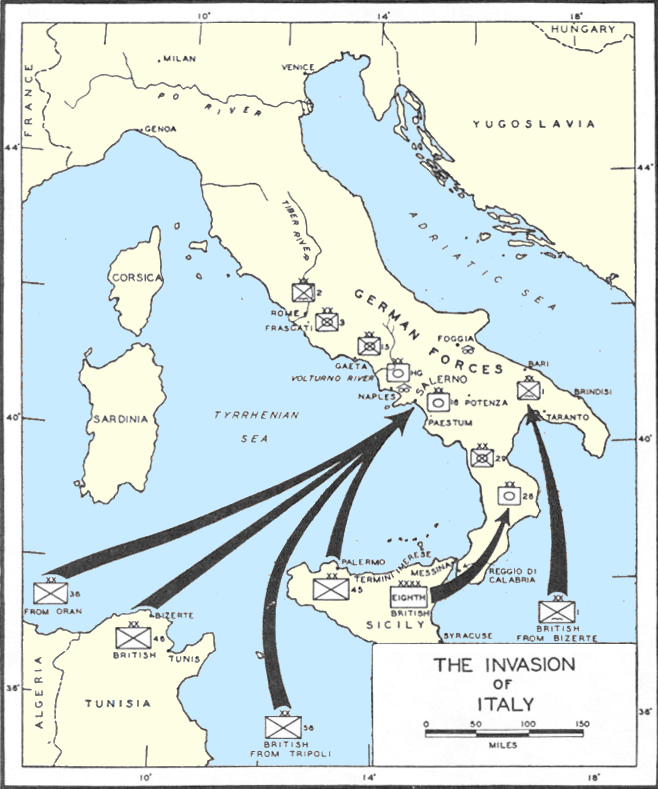

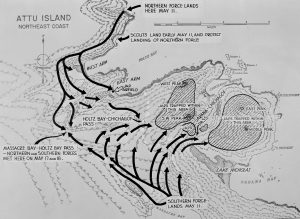

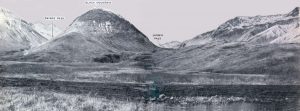

Despite these obstacles, Brown tried to make the best of a bad situation, effecting two landings on May 11, 1943. The Northern Landing Force came ashore near Holtz Bay; the Southern Landing Force at Massacre Bay. A Scout Battalion, led by Captain William Willoughby, was offloaded from submarines on Beach Scarlet, to prevent the Japanese from moving west and prolonging the fight. There was to be a quick link-up of the forces. The plan was to force the Japanese back toward Chichagof Harbor, where they could be killed or captured. It was supposed to be over quickly.

The Northern Force’s landing started uneventfully, but surprise was lost when Japanese sentries spotted the forces through the fog. Artillery fire halted the American advance. At Massacre Bay, the Americans were able to move inland for about a mile before encountering fierce Japanese resistance. Japanese machine gunners, dug in on ridge lines and hidden by the ever-present fog, poured fired down on the advancing troops, killing many, including the Southern Force’s commander. The attack bogged down, with men freezing in the snow, or suffering frostbite, and equipment stuck in the muskeg. For five days, the green American troops at Massacre Bay got nowhere. Because tractors couldn’t move in the muck of snow and muskeg, a huge traffic jam grew at the water’s edge. Everything had to be hand carried. Artillery pieces would fire from the water’s edge, driving the gun into the muck – to be dug out after each shell was fired. Despite having warned of a difficult landing, General Brown was relieved of command.

The Northern Force had better luck, and was aided by a naval bombardment from the battleships Pennsylvania and Idaho and several cruisers. It was still very slow going, marked by extreme acts of bravery on the part of the advancing Americans. One example was Private Joe P. Martinez, of Taos, New Mexico. An automatic rifleman in Company K of the 32nd Infantry, he singled-handedly walked into enemy fire armed only with a Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), and killed five Japanese soldiers. He reached the crest of a contested ridge before he collapsed with a mortal wound. His stalled company cleared the remaining Japanese off the ridgeline. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

The scouts under Willoughby had better luck until they too found themselves bogged down on a wind-blown open ridge in a stand-off with Japanese infantry.

Finally, after four days, the Japanese force in front of the Northern attackers abandoned Holtz Bay, and soon after Willoughby’s scout force broke through. Of the 420 men he started with, only 165 were still able to fight – some had been killed, but most suffered from exhaustion, frostbite, and gangrene. Amputations became commonplace.

By day seven, the Americans had over 12,000 men on the island. They had suffered over 1100 casualties, of which 500 were from exposure. They were up against the remaining 2000 Japanese, who were skillfully withdrawing into more defensible positions. After holding off the Southern Force for eight days, the enemy made an orderly withdrawal toward heights protecting Chichagof Bay.

Even as they inflicted fearsome casualties, the Japanese were going through a hell of their own. Although better equipped for the weather, they were exhausted from the constant skirmishing, artillery bombardment, and lack of food. An unknown Japanese NCO’s diary of May 20th reads, “The hours are long. Could do any type of hard work if I could only get two rice-balls a day. I haven’t slept for the past eight days. We received fierce naval gun fire.” Eventually the Japanese perimeter shrunk back toward Chichagof Bay. A last ditch attempt by the Japanese air forces flying from the Kurile Islands to assist their comrades proved disastrous when nine of sixteen bombers were shot down. It was the last outside assistance Japanese defenders received. Finally, on May 28, 1943, a key ridgeline called the Fish Hook fell. Rather than slaughter the remaining defenders, the Americans attempted to persuade them to surrender since Japanese were down to 800 able bodied soldiers, but Japan’s unbending Bushido warrior code, which equated surrender with cowardice, rendered this effort fruitless. The last desperate act by the Japanese was at hand. But first, the 400 wounded soldiers in the field hospital were killed by fellow Japanese, either by grenades or with morphine.

A diary from a medical officer, Nebu Tasuguchi records some of their horrific end. MAY 29, 1943 TODAY AT 2000 WE ASSEMBLED IN FRONT OF HQS. THE FIELD HOSPITAL TOOK PART TOO. THE LAST ASSAULT IS TO BE CARRIED OUT. ALL THE PATIENTS IN THE HOSPITAL WERE TO COMMIT SUICIDE. ONLY 33 YEARS OF LIVING AND I AM TO DIE HERE. I HAVE NO REGRETS. BANZAI TO THE EM-PEROR…. AT 1800 TOOK CARE OF ALL THE PATIENTS WITH GRENADES.

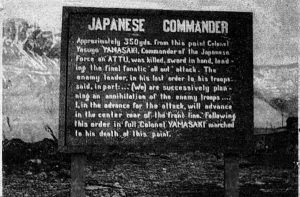

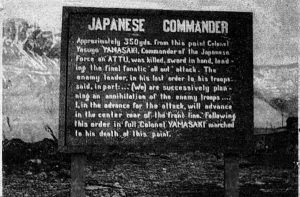

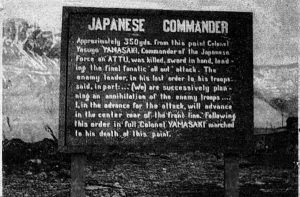

The Japanese commander, Colonel Yatsuyo Yamasaki, led the remaining men, many without weapons, on a sneak attack on the American perimeter. The suicidal charge was totally unexpected. Crazed attackers overran a command post and charged into a medical clearing station, killing most of the patients. Grabbing cooks, litter bearers, road builders and anyone else who could fire an M-1, the Americans re-assembled. “The 50th Engineers [writes Brian Garfield] rushing forward to man the lines, met the charge head-on with bayonets and clubbed rifles.” The onslaught failed. Colonel Yamasaki died in a final futile charge. The next day, the surviving 500 Japanese committed mass suicide by exploding grenades against their chests. The agony of Attu was over.

What was supposed to be a three day walk-over had taken three weeks. Twenty eight Japanese were taken prisoner. Well over 2500 Japanese were killed – the exact number is not known. The Americans suffered 549 combat deaths, and over 1000 wounded, or evacuated because of frostbite, exposure or combat fatigue. Garfield notes that “In proportion to the numbers of troops engaged, [Attu] would rank as the second most costly American battle in the Pacific Theater-second only to Iwo Jima.”

American commanders were shocked at the cost. If Attu was this pricey, what would Kiska be like? The invasion planners reassessed the support the next invasion would require. The blockade of Kiska tightened until it became impenetrable. Bombers flew an average of five missions a day against the island’s defenses. Radar equipped PV-1 Ventura bombers were able to bomb through the clouds and fog.

Round the clock bombing kept Japanese defenders in a labyrinth of sophisticated caves and tunnels, except when attempting to repair bomb damage. Food became even scarcer. Whenever stray American bombs detonated in the harbor, Japanese would rush to scoop up dead fish, which they called “Roosevelt rations.”

Increased radio traffic convinced the defenders that the assault on Kiska was imminent. The huge Japanese submarines based in the Kuriles, called I-boats, were ordered to evacuate the island, but the Americans quickly sunk three of the eight I-boats before they could escape. In desperation, Admiral Shiro Kawase assembled a small flotilla of cruisers and destroyers, and made a run to save the defenders. The blockading American fleet involved itself in the folly later known as the “Battle of the Pips”, firing countless rounds into an open sea in response to false radar images, and then had to re-fuel. On July 28th, 1943, Kiwase’s small flotilla slid into Kiska undetected and evacuated all 5183 men in less than an hour. “Kawase had brought off one of the war’s most imaginative and daring maneuvers [writes Garfield] without a single casualty.”

Amazingly, the Americans remained unaware of the evacuation. For three weeks the Americans kept pummeling Sitka. Pilots reported no anti-aircraft bursts, nor any repairs to recent bombings. Higher-ups took no chances, choosing to believe the Japanese had merely retreated further inland to caves and redoubts. On August 15th, 34,426 American and Canadian troops landed on Sitka – and were met by a few stray dogs. The only casualties were caused by friendly fire. The Japanese had had the last laugh. They had tied up over 300,000 Allied soldiers and sailors, as well as a fleet of ships, to attack a deserted island. General Buckner wryly noted, “To attract maximum attention, it’s hard to find anything more effect that a great big, juicy, expensive mistake.” But it was still a retreat, still a defeat of Imperial Japan’s ambitions. 439 days of warfare for a cold and miserable part of the United States was over. Bombing runs to Japan’s Kurile Islands began – more for harassment that anything else. General Buckner wanted to plan an invasion of Japan from the north – and while that idea was shelved, fear of its possibility kept over 40,000 Japanese soldiers and sailors and 500 aircraft defending those approaches as the war crept toward Japan’s main islands from the south.

(Much information for these articles was gleaned from The Thousand Mile War, by Brian Garfield, as well as naval and other histories)

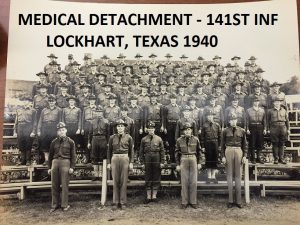

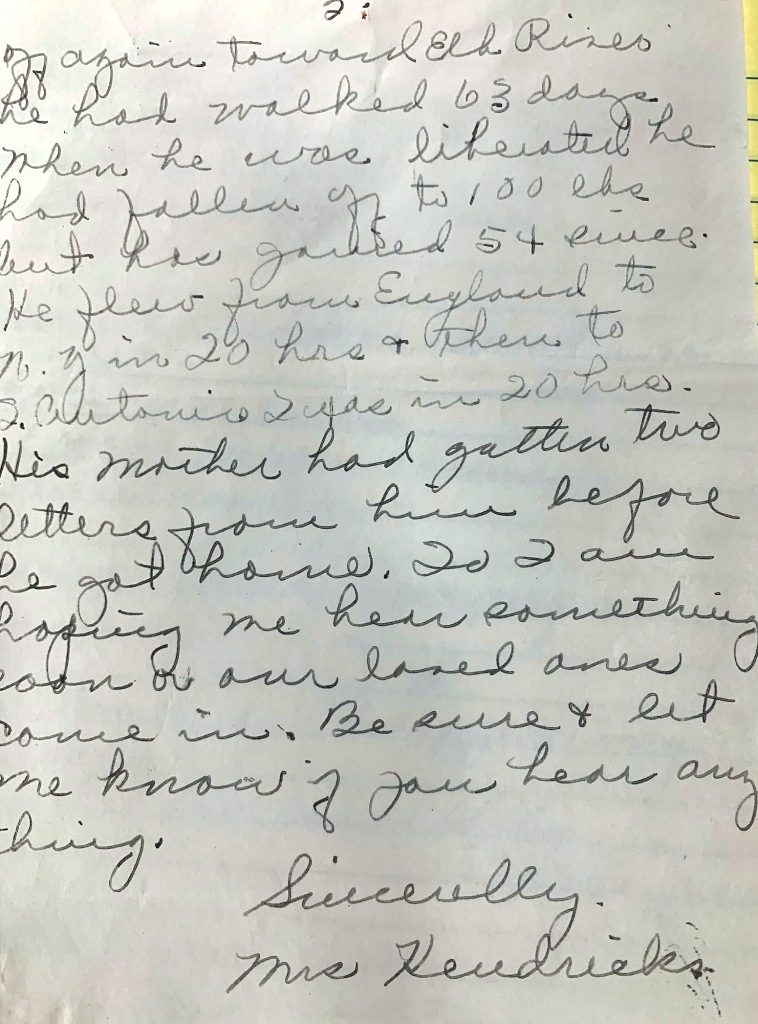

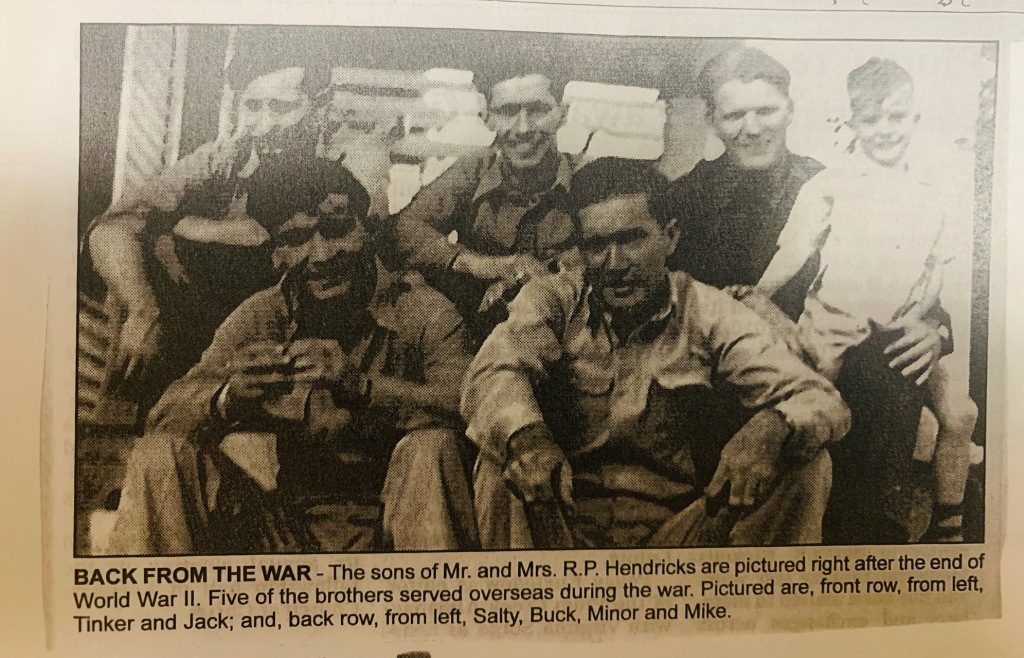

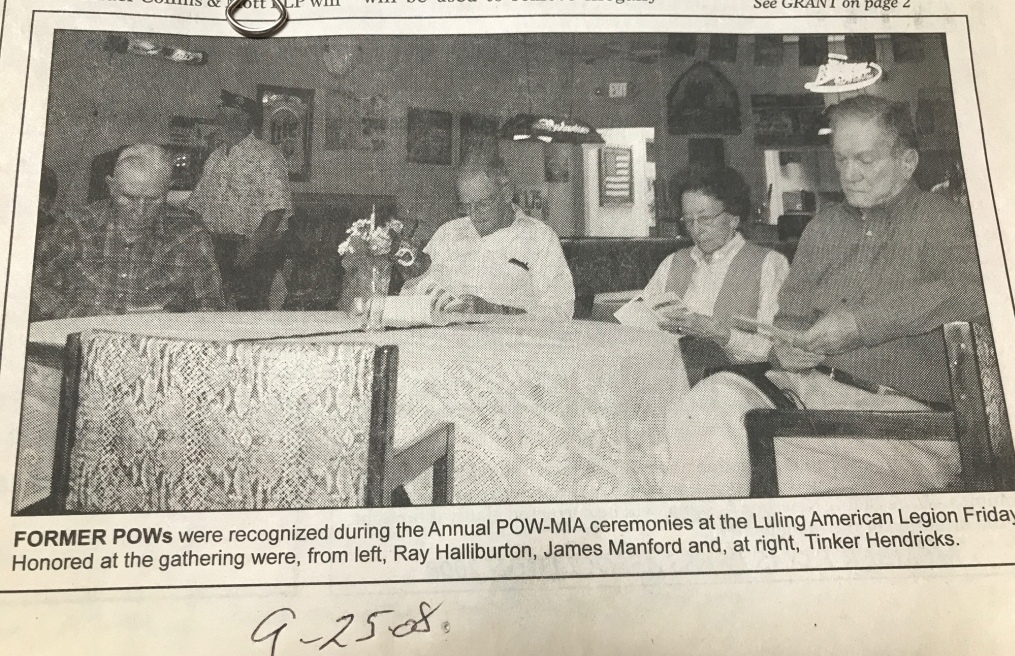

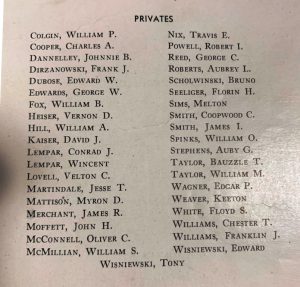

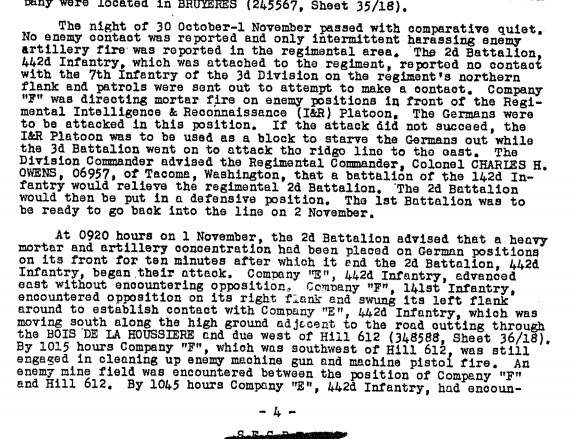

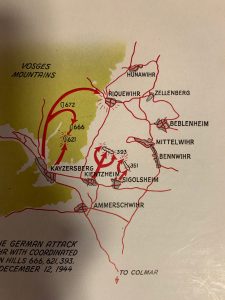

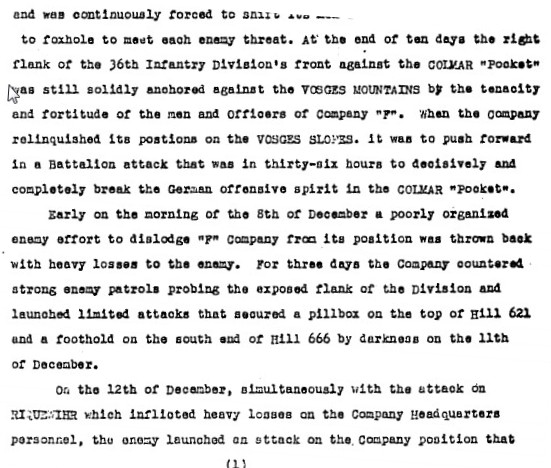

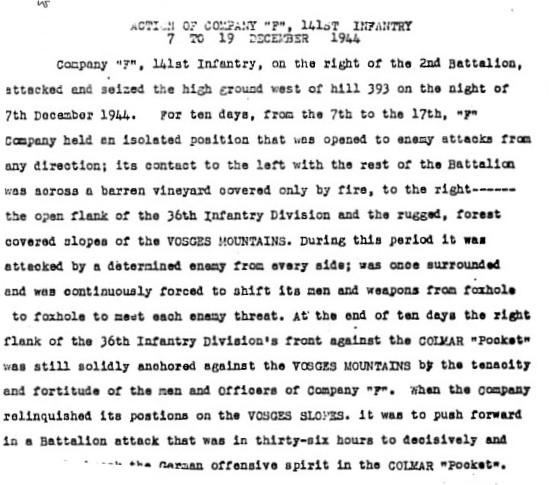

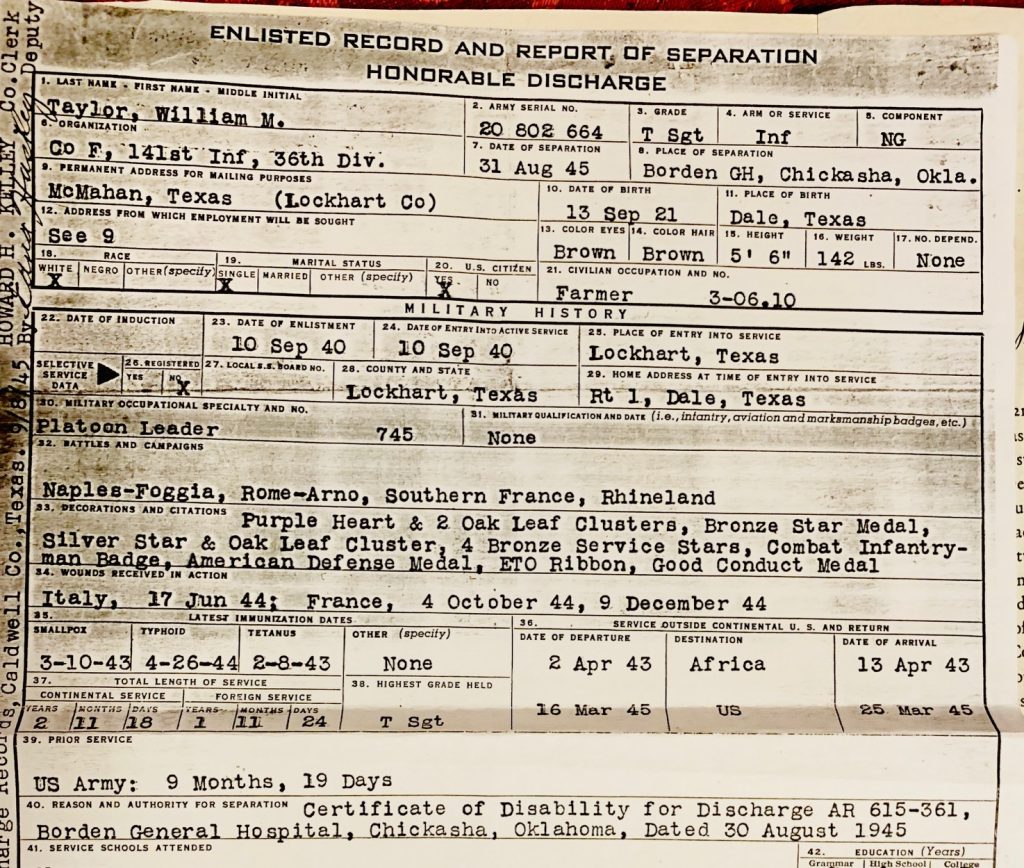

encouraged by older brother Bauzzle, on September 10, 1940, he enlisted at Lockhart in the Texas National Guard’s Company F, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th “Texas” Infantry Division.

encouraged by older brother Bauzzle, on September 10, 1940, he enlisted at Lockhart in the Texas National Guard’s Company F, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th “Texas” Infantry Division.

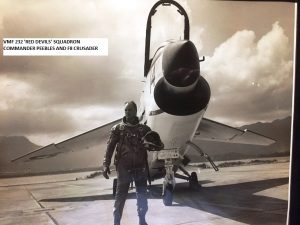

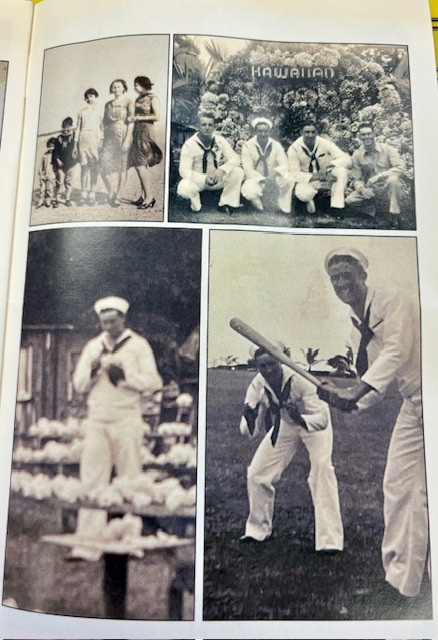

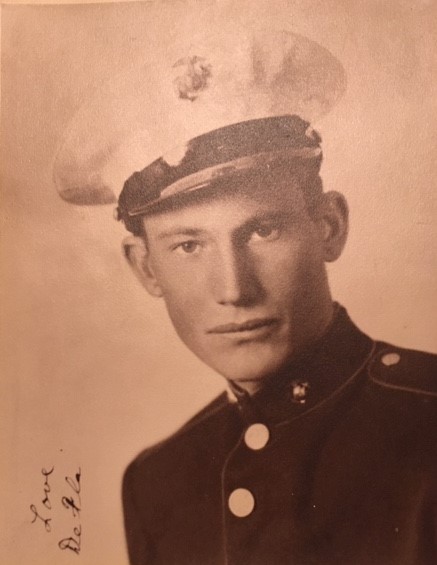

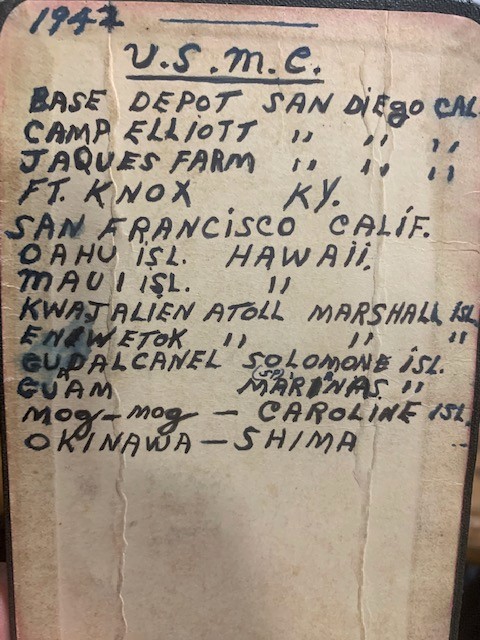

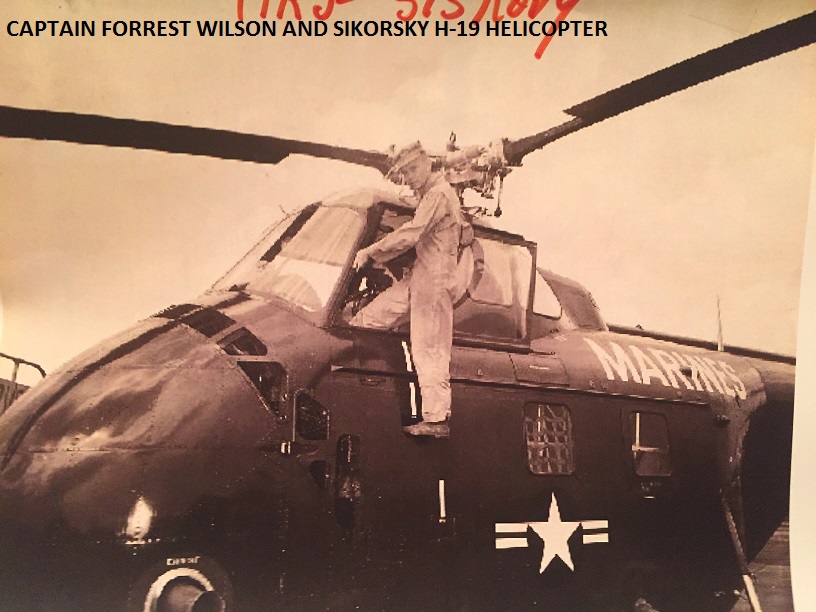

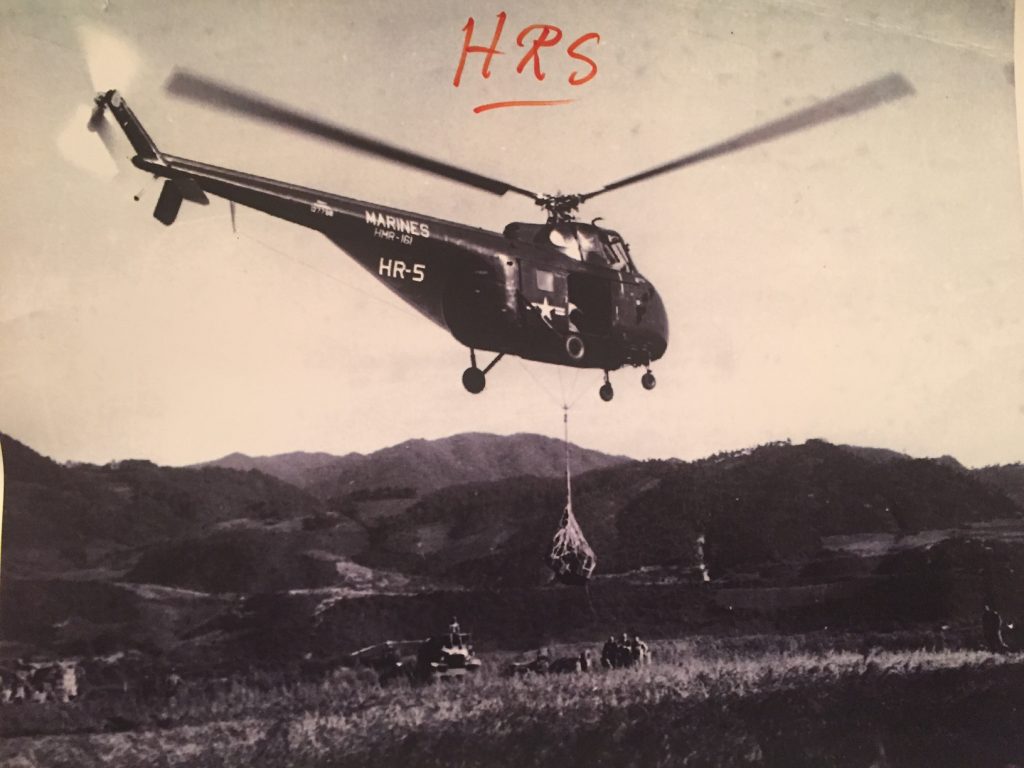

1954. Duty stations included Kaneohe Marine Air Station in Hawaii. In 1959, he became squadron commander of VMF 232, flying F8 Crusaders. In 1967, Colonel Peebles served in Viet Nam as air officer attached to amphibious operations.

1954. Duty stations included Kaneohe Marine Air Station in Hawaii. In 1959, he became squadron commander of VMF 232, flying F8 Crusaders. In 1967, Colonel Peebles served in Viet Nam as air officer attached to amphibious operations.