COL. KENNETH BYRD “KEN” WHITTEMORE

HOW THE BYRD LEARNED TO FLY

By Todd Blomerth

On October 6, 1954, 2nd Lieutenant Kenneth Whittemore took off on a training mission in an F-86D from Sioux City, Iowa. Suddenly, the engine of his fighter exploded. Too low to bail out, Ken opted to crash-land in a farmer’s field just across the Missouri River in Nebraska. He sprinted from the burning aircraft. Pausing to catch his breath, he turned to see the plane explode. Ken recalled, “As I sat beside a road awaiting the crash crew to arrive, a farmer came up and asked me if my combine was on fire!!”

How an impoverished child of the Great Depression wound up flying sophisticated jet aircraft is a story of determination, skill, and, Ken is absolutely convinced, God’s  grace.

grace.

Kenneth Byrd Whittemore was born in Red Bank, Tennessee on June 26, 1930. His parents, Byrd Whittemore and Naomi (Harvey) Whittemore, were factory workers. In the depths of the Depression, Ken and his brother Eugene moved from place to place. His parents divorced when he was ten, and eventually his father became the custodial parent. Life wasn’t easy. Somehow, Ken made the most of it. While living with his father in a rented room in downtown Chattanooga, he would often skip school and use his ten cents of lunch money to watch double features at the Cameo and Dixie movie theaters.

In the summers, he was farmed out to various aunts and uncles in Tennessee and Georgia. While in Elberton, Georgia, he was baptized by the local Methodist preacher, who happened to by his Uncle Alton. Once, when visiting his Uncle Max, he was exposed to polio by his cousin and quarantined for several weeks.

Byrd Whittemore remarried, but this did not provide any geographic stability. Byrd became a barber, and worked at Fort Oglethorpe and Dalton, Georgia, before moving back to Chattanooga where Ken graduated from Central High School in 1947. The school had an ROTC program. Ken found he enjoyed its structure.

Enrolling in Reinhardt College, a small Methodist school in Georgia, and short of funds as usual, Ken enlisted in the Georgia National Guard. The three dollars drill money was a Godsend.

Ken graduated from college two months before the North Koreans invaded the South. A draft notice was inevitable. The misery of National Guard summer camps at Fort Jackson, South Carolina dissuaded Ken from a career in the infantry, so he enlisted in the US Air Force. After completing courses at the USAF’s Supply School, Ken was assigned to the newly- reactivated San Marcos Air Force Base (renamed Gary Air Force Base in 1953, it now contains Gary Job Corps Center, and San Marcos Regional Airport). Almost completely shut down at the end of World War II, the facilities were primitive. No street lights. Barracks in disrepair. Runways and taxiways in sad shape.

That said, the young enlisted man thoroughly enjoyed his time there. Ken convinced his boss, Tech Sergeant Charlie Chester Brooks, that, because of the ‘valuable inventory’ of band instruments and athletic equipment in the Personnel Supply Room, it was necessary for Ken to sleep in the Supply Room’s isolated building. He avoided the bustle and lack of privacy of barracks living. Relief pitcher for the baseball team, he traveled to other bases. However, there had to be more to life than this.

Luckily, the Air Force was looking for pilot trainees. Not surprisingly, Ken was accepted into the single engine jet pilot program. Getting into the program was much easier than staying in. While at the Southern Airways training school, Ken remembers, “I soon realized that I needed help getting through this program, and I prayed to God for His help. He not only gave it, but has stayed with me ever since.”

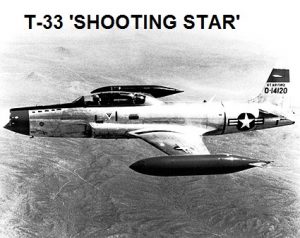

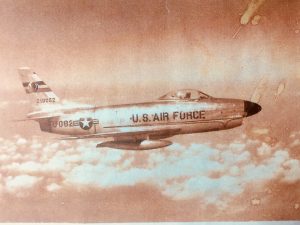

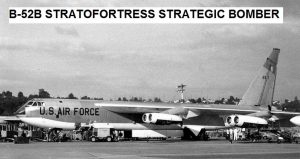

Three of the aircraft Lt. Col. Ken Whittemore trained in

While training at Laredo Air Force Base, Ken took his 1937 Nash to the dealership for servicing. While standing around, he was introduced to a beautiful schoolteacher from San Marcos who was teaching in Laredo. They fell in love almost at once, marrying on October 17, 1953, just two months after their first meeting. Loraine Brooks, whose Texas frontier roots run very deep, proved to be a perfect mate. Ken and Loraine have been married for sixty-five years.

The following years passed in a flurry of radar and interceptor training and assignments. Some were short. Others longer. The peripatetic military life saw Ken and Loraine in Panama City, Florida, and Sioux City, Iowa, where the Whittemore’s first son, John Michael was born in April 1954.

In November 1954, 1st Lt. Whittemore’s squadron was assigned to RAF Station Bentwaters, England. John Michael was too young to cross the Atlantic on a ship, and he and his mother were required to fly. Lucky for them. Ken recalls “rough seas, kippered herring for breakfasts, and sea sickness.” After three years in England, it was time to rotate home, this time to Shaw AFB, South Carolina. Here, their son David Mark was born. It was a joyous time, and eased the sadness of the loss of an infant daughter Karen Marie, who was just three days old when she died in England.

1ST LIEUTENANT WHITTEMORE OVER THE NORTH SEA IN F-86D

Being a desk jockey wasn’t in Ken’s blood. After eighteen months as a staff officer, he volunteered for the Strategic Air Command (SAC). Some may not recall just how important SAC was to the nation’s defense during the 50s and 60s. The Soviet Union, nuclear capable, made no secret of its willingness to use those weapons. The Cold War was often in danger of turning white hot. A SAC assignment required a commitment far greater than was ordinarily expected of most service personnel. Nuclear weapons delivery, survival, and B-52 flight training were completed. In the meantime, Loraine gave birth to the couple’s third son, Paul Stewart. She and the three boys rejoined her husband at his new duty station – Biggs AFB in El Paso, Texas.

Captain Whittemore’s first assignment was with the 334th Bomb Squadron as a co-pilot of the massive bomber. To say that SAC training was intense is an understatement. There was zero tolerance for mistakes. On one occasion, his crew’s gunner missed the answer to one test question. The entire crew was confined to a room for two hours. The crew then re-took the test. Everyone aced the exam this time. The crews trained, flew and spent much time together on ground alert. Crews were tested constantly. Ken recalls, “There were three kinds of tests: Alpha, Bravo, and Coco. For Alpha, all crewmen went to the plane and strapped in their seats. During Bravo, crew members strapped in and started engines and then cut them off. For Coco, the crew strapped in, started engines, taxied onto the runway, and simulated takeoff by taxiing to the far end of the runway and then returning to the parking place.”

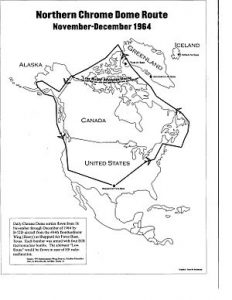

Nuclear Airborne Alert Missions, with thermonuclear weapons, were flown frequently. These flights originated and ended at Biggs AFB, with much time over the polar regions of Northern Canada. Beginning in 1960, one-third (this later went to one-half) of the Squadron’s aircraft were on fifteen minute alert, fully armed, fueled, and ready for combat, all to reduce the vulnerability of a Soviet nuclear attack.

In 1963, Ken was promoted to B-52 Aircraft Commander. If anything, the pressure became more intense. With names like Chrome Dome, Hard Head, Round Robin, and Head Start, SAC kept nuclear-armed B-52s in the air constantly, flying routes near the Soviet Union’s borders. Each bomber crew had specific targets it was to attack in the event of a war. The Soviet Union had similar strategies aimed at the U.S. Ken’s B-52, refueled midair by KC-135s, flew missions often lasting twenty-two hours! Thankfully for mankind, no thermonuclear weapons were ever needed. Those of us living in the 1960s can well recall the bomb shelters, drills, and gallows humor that went with the ever-present threat of ‘what could happen.’

On August 4, 1964 the Tonkin Gulf Incident occurred. North Vietnamese torpedo boats apparently (the event is still the subject of intense controversy) attacked an American warship lying off the coast of North Vietnam. Congress’s Tonkin Resolution led to the substantial escalation in an already bloody conflict.

The B model Stratofortress was being decommissioned. Ken was intent to on ‘getting into the war,’ but not flying another version of the huge bomber. Anti-aircraft defenses in North Vietnam were substantial. “I had no intention of flying over Hanoi in a B-52.” In November 1965, he received notice that he would be going to Southeast Asia within the year. First, he had to learn to fly the F-105 Thunderchief (endearingly nicknamed the ‘Thud’). During that time, Ken and Loraine decided that the family needed a stable home base. Loraine’s parents were living in San Marcos, so the two searched for a house nearby. In 1966, they purchased a house on Maple Street in Lockhart. They continue to live there today.

The supersonic single seat F-105D Thunderchief conducted the majority of the strike bombing missions in the early days of the Vietnam War. The massive fighter bomber could carry up to 14,000 pounds of armament, more than a World War II B-17 or B24. The two seater variant, the F-105G was dubbed the ‘Wild Weasel,’ and was designed for anti-aircraft missile suppression.

F-105D with full bomb load

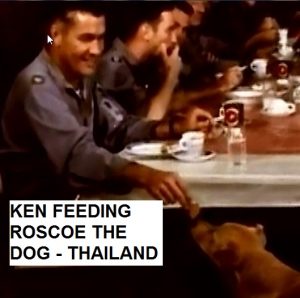

On July 22, 1966, Major Ken Whittemore reported to Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base for assignment to the 421st Tactical Fighter Squadron. Between then and January 1967, he flew over one hundred missions. All but four were over North Vietnam.

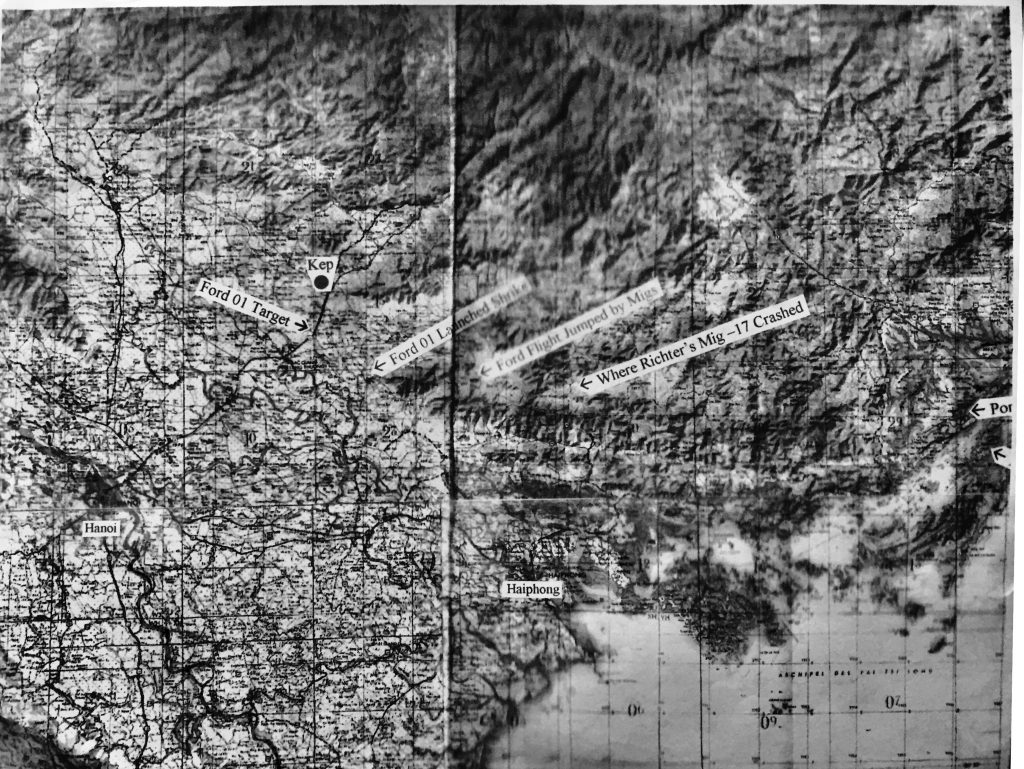

In 1965, the U.S created Route Packages, dividing regions of North Vietnam for air missions. Route Package Six (Pac 6), around Hanoi and its port of Haiphong, held the deadliest concentration of anti-aircraft weaponry in the world. Other Pacs were only marginally safer to attacking bombers.

Ken describes a ‘routine’ mission:

“The method of delivery was to approach the target at an altitude of around five to six thousand feet, with the throttle in afterburner. The altitude was determined by the area defenses, and the afterburner gave us a very high speed. At a preplanned point we would begin a rapid climb to about fifteen thousand feet and at an air speed of 350 knots, roll over into a steep dive, aim at the target, release the bombs at six thousand feet, and get the heck out of there.”

On one occasion, his empty external wing fuel tank took an anti-aircraft round, rather than his left wing. “I jettisoned the tank, and the plane settled down,” He recalls. “I did not want to bail out up there. That was pretty exciting and another reminder that God had His eye on me.”

The Wild Weasels would fly with bomber formations. The two-seaters were tasked with attacking surface to air missile (SAM) sites before their weapons could be launched. It was a deadly cat-and-mouse game, played daily.

Two missions stand out in Ken’s memory. The first was an attack on a railroad and highway bridge at Dap Cau, about twenty miles northeast of Hanoi. Ken was part of Ford Flight, a Wild Weasel-led contingent of four aircraft intent on protecting a large attack force from SAMs. Ford Flight entered North Vietnam from the Tonkin Gulf, when two MiG 17s began tracking the lead two aircraft, but not seeing the trailing two. Lt. Karl Richter scored a rare ‘kill’ on the unsuspecting enemy. Do Huy Hoang, the MiG’s pilot, bailed out, and survived the war. Richter would be shot down and die ten months later.

The second was an attack on a railroad bridge in Pac 5. After dropping his bombs and strafing a train, a pilot radioed Major Whittemore that his aircraft had been hit. He escorted the stricken fighter-bomber, and stayed on station long enough to ensure that a rescue helicopter was able to retrieve the pilot. Another pilot in the four aircraft flight was not seen again.

And so it went, day after deadly day. In the words of one F-105 pilot, “There was simply no room for error.” Over three hundred and fifty F-105s were lost in the conflict. Many young crewmen never came home. The reasons were many: the F-105 was originally a nuclear strike aircraft. It wasn’t designed for the mission, but served admirably until replaced by newer aircraft. Russian ‘advisors’ to the North Vietnamese ensured they received state-of-the-art radar and missiles. The American commanders insisted on certain attack corridors in the north. The predictability played into the hands of the enemy.

Ken Whittemore was one of the lucky ones.

Lt. Colonel Whittemore’s last assignment in the Air Force was Chief of Safety at Laredo AFB. He retired in 1972. Lockhart became Ken’s ‘permanent duty station.’

Ken became the Lockhart Chamber of Commerce manager for two years and was instrumental in the creation of the Chamber’s Chisholm Trail Roundup. Then, working under Joe Rector, Ken helped in the change-over from Lockhart’s collection office to the Caldwell County Central Appraisal District. Meanwhile, Loraine, a gifted teacher and counselor, worked for Lockhart ISD, mentoring countless children, until her retirement in 1990.

Ken returned to college, earning a degree from Southwest Texas State University in 1977, and finished his formal schooling with completion of an electronic tech course at Texas A&M in 1980.

For years Ken could be found most mornings at the Lockhart State Park, intent on getting in eighteen holes of golf. The couple remains actively involved in the lives of their sons, grandchildren and great grandchildren.

Lt. Colonel Whittemore’s career was, to say the least, exciting. During his tenure, he flew nine different types of aircraft including cargo, fighters, reconnaissance, trainers and heavy bombers. Among his many awards: the Distinguished Flying Cross and eleven Air Medals. He is, quite rightly, extremely proud to have had the opportunity to serve our country.

Be sure to thank him for his devotion to duty. He’ll be the first to tell you to not forget Loraine. Without her love and support, he couldn’t have done it.

“I FEEL PRIVILEGED THAT I HAVE LIVED AN EXCITING LIFE”

Lt. Col. Ken Whittemore USAF (retired) – 2018