A TRIBUTE TO A QUIET MAN

By Todd Blomerth

He is 91 years old now. When he speaks about his life you sense that despite his chronological age he is much younger at heart. He is a quiet and modest man, not prone to boasting. He tends to minimize a series of events that few of us can imagine living through. His is a story worthy of recalling.

His name is Thomas C. Holland. Tom, or Tommy, as he goes by, was born in Lockhart in 1922. He has been a resident of Caldwell County almost all his life. Tommy’s dad, Cleveland (he went by “Cleve”) was a respected construction supervisor for Holland Page, a large construction company and traveled extensively to job sites in Texas and Oklahoma. Tommy and his younger sister Georgia were mostly raised by Albert and Myrtle Schneider. The Schneiders lived at 1217 Woodlawn Street in Lockhart. Cleve often helped Caldwell County men get jobs during the late 30s and during World War II. During summer breaks and after high school graduation, Tommy would travel with his dad and work with construction crews. Georgia would occasionally travel with them. Bridge City and Lubbock were two of the places he worked. Slight and wiry, Tommy shoveled a lot of sand and gravel for concrete jobs. He had to be tough. There was no pre-mix in those days.

In 1942, Uncle Sam sent an invitation to Tommy to join his armed  forces. In other words, he was drafted. When he was three, he had fallen into a wash pot. The burns scarred an arm. Despite all evidence to the contrary, the Army thought the scarring had limited his strength and mobility. Much to his disgust, after basic training he was assigned as a clerk at an army airbase in Mississippi. In December of 1942 he was reevaluated. He reiterated to the Army doctors that there was absolutely nothing wrong with him, and that he wanted to be allowed normal duties. He got his wish. Knowing it was a quick way to earn sergeant’s stripes, he opted for gunnery school. After graduation from gunnery school in Harlingen, Texas, the Army sent him to aircraft mechanic school as Keesler Army Air Base in Mississippi. Then, because he applied to be a pilot, he was enrolled in the University of Alabama under the Army Air Force aviation cadet program. Designed for young men with only high school educations, it was intended to help turn them into “officers and gentlemen.” After six months of college level courses, he was transferred to an airbase in San Antonio. Pilot graduation rates often depended on the number of pilots needed. With an over abundance of pilots at the time, Tommy did not become ‘an officer and a gentleman.’ Instead, he was assigned as a tail gunner on a B-17 and sent to MacDill Field in Florida to begin crew training.

forces. In other words, he was drafted. When he was three, he had fallen into a wash pot. The burns scarred an arm. Despite all evidence to the contrary, the Army thought the scarring had limited his strength and mobility. Much to his disgust, after basic training he was assigned as a clerk at an army airbase in Mississippi. In December of 1942 he was reevaluated. He reiterated to the Army doctors that there was absolutely nothing wrong with him, and that he wanted to be allowed normal duties. He got his wish. Knowing it was a quick way to earn sergeant’s stripes, he opted for gunnery school. After graduation from gunnery school in Harlingen, Texas, the Army sent him to aircraft mechanic school as Keesler Army Air Base in Mississippi. Then, because he applied to be a pilot, he was enrolled in the University of Alabama under the Army Air Force aviation cadet program. Designed for young men with only high school educations, it was intended to help turn them into “officers and gentlemen.” After six months of college level courses, he was transferred to an airbase in San Antonio. Pilot graduation rates often depended on the number of pilots needed. With an over abundance of pilots at the time, Tommy did not become ‘an officer and a gentleman.’ Instead, he was assigned as a tail gunner on a B-17 and sent to MacDill Field in Florida to begin crew training.

,

THE HOYER B-17 CREW – EARLY 1944

Standing, L-R

S/Sgt Bernard Duwel, ENG

Lt. Charles Pearson, B

Lt. WIlliam Hoyer, P

Lt. Joseph Syoen, CP

Lt. John Riddell, N

Kneeling, L-R:

Sgt. Thomas C. Holland, TG

Sgt. Floyd Broman, WG

S/Sgt Walter Degutis, WG

Sgt Edward Thornton, WG

S/Sgt Thomas Burke, BTG

His ten-man crew began training on Boeing Aircraft’s B-17. Dubbed the Flying Fortress, it was a magnificent aircraft, and was rightly loved by those who flew in her. The crew became close, as one would expect. They trained as if their lives depended on it-because it would. The life expectancy of a bomber crew in Europe was about two weeks. In late May, 1944 the crew received its orders assigning it and their bomber to the U.S. 8th Air Force’s 709th Bombardment Squadron, 447th Bombardment Group based at Rattlesden, England near Bury St. Edmunds. Lt. Hoyer’s crew was given a brand new B-17 at Hunter Field outside of Savannah, Georgia. Because the B-17 was a four-engine aircraft, the crew flew the extremely hazardous northern route across the Atlantic, through Newfoundland and Greenland. Weather was problematic to say the least. Along with other aircraft, their bomber was grounded in Greenland by winds so violent the crew had to feather the propellers to keep the engines from being damaged. In the midst of the horrific weather, word came on June 6, 1944 that the Allies had invaded German controlled Europe. Despite the weather, base officials told the many stranded crews to head to England. And so they did.

two weeks. In late May, 1944 the crew received its orders assigning it and their bomber to the U.S. 8th Air Force’s 709th Bombardment Squadron, 447th Bombardment Group based at Rattlesden, England near Bury St. Edmunds. Lt. Hoyer’s crew was given a brand new B-17 at Hunter Field outside of Savannah, Georgia. Because the B-17 was a four-engine aircraft, the crew flew the extremely hazardous northern route across the Atlantic, through Newfoundland and Greenland. Weather was problematic to say the least. Along with other aircraft, their bomber was grounded in Greenland by winds so violent the crew had to feather the propellers to keep the engines from being damaged. In the midst of the horrific weather, word came on June 6, 1944 that the Allies had invaded German controlled Europe. Despite the weather, base officials told the many stranded crews to head to England. And so they did.

Much to the crew’s disappointment, upon arrival in England, their brand new B-17 was taken away from them. It would be used by more experienced crews. They would be stuck with whatever aircraft was assigned them. Like all fresh aircrews, the Hoyer crew was split up for its first missions, in order to ensure the crewmen and pilots were familiar with combat formations and tactics. Tommy’s first mission, on June 24, 1944, was either to Blanc Pignon Ferme or Wesermude – he can’t recall which as there were simultaneous attacks planned. Neither was successful, and both bomber formations came back with their bombs, as neither target was visible through heavy cloud cover.

His second mission, on June 25, 1944, again with another crew, was to Area #1 of Operation “Zebra.” After a 2 a.m. briefing, the Group’s B-17s flew to Vercors, west of Grenoble, France. Instead of dropping bombs, the planes dropped 420 canisters containing ammunition, supplies, and weapons for the French resistance fighters in the area. Several OSS (the forerunner of the CIA) agents also parachute jumped in.

On June 28, 1944, and again with another crew, Tommy manned the tail guns for a run toward a target in France. Weather obscured the primary target so an airfield at Denian/Prouvy, France was hit instead.

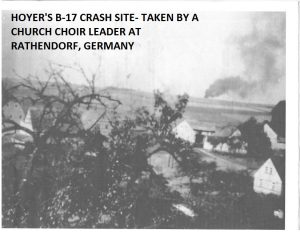

On June 29, 1944, the Hoyer crew was reunited for its first combat mission. The target was an oil refinery at Bohlen, Germany. The crew briefing was at 2:30 a.m. At 4:50 a.m. dozens of Flying Fortresses, loaded with 100 pound bombs, started taking off. With the intercom-connected crews donning oxygen masks and heated  clothing, the B-17s lumbered to an altitude of 24,000 feet. They were supported by fighter aircraft. German Bf 109s and Focke Wulf190s shot down many bombers during the war, but the greatest danger by far was anti-aircraft artillery. Nearing Bohlen, flak from German anti-aircraft guns began reaching for the Americans. Tommy had been told that if you saw flak, you were probably okay. However if you could hear it, you had better watch out. He could hear the flak “very well.” Just as Lt. Charles Pearson, the plane’s bombardier, finished releasing the bombs, flak hit near the Number 2 engine. Some of the crew was injured by shrapnel. Fuel streamed back, and then erupted in fire. Lt. William Hoyer’s last words heard by Tommy were, “let’s bail the hell out of this thing.”

clothing, the B-17s lumbered to an altitude of 24,000 feet. They were supported by fighter aircraft. German Bf 109s and Focke Wulf190s shot down many bombers during the war, but the greatest danger by far was anti-aircraft artillery. Nearing Bohlen, flak from German anti-aircraft guns began reaching for the Americans. Tommy had been told that if you saw flak, you were probably okay. However if you could hear it, you had better watch out. He could hear the flak “very well.” Just as Lt. Charles Pearson, the plane’s bombardier, finished releasing the bombs, flak hit near the Number 2 engine. Some of the crew was injured by shrapnel. Fuel streamed back, and then erupted in fire. Lt. William Hoyer’s last words heard by Tommy were, “let’s bail the hell out of this thing.”

The B-17 tail gunner was the most isolated member of the crew. He did have one advantage however – his own escape hatch. Tommy didn’t need to be told twice. Throwing off his oxygen mask, helmet, and intercom connections and snapping on his parachute, he jettisoned the escape hatch and flung himself out of the plane. The shock of the parachute deploying knocked him unconscious momentarily. When he came to, he was floating under a canopy deep in enemy territory. “I seemed to all alone,” Tommy remembers. “I wondered if my insurance would pay off if something else happened.” Since he was alive, he worried that his dad and the Schneiders would not know for some time that he had survived.

The B-17 tail gunner was the most isolated member of the crew. He did have one advantage however – his own escape hatch. Tommy didn’t need to be told twice. Throwing off his oxygen mask, helmet, and intercom connections and snapping on his parachute, he jettisoned the escape hatch and flung himself out of the plane. The shock of the parachute deploying knocked him unconscious momentarily. When he came to, he was floating under a canopy deep in enemy territory. “I seemed to all alone,” Tommy remembers. “I wondered if my insurance would pay off if something else happened.” Since he was alive, he worried that his dad and the Schneiders would not know for some time that he had survived.

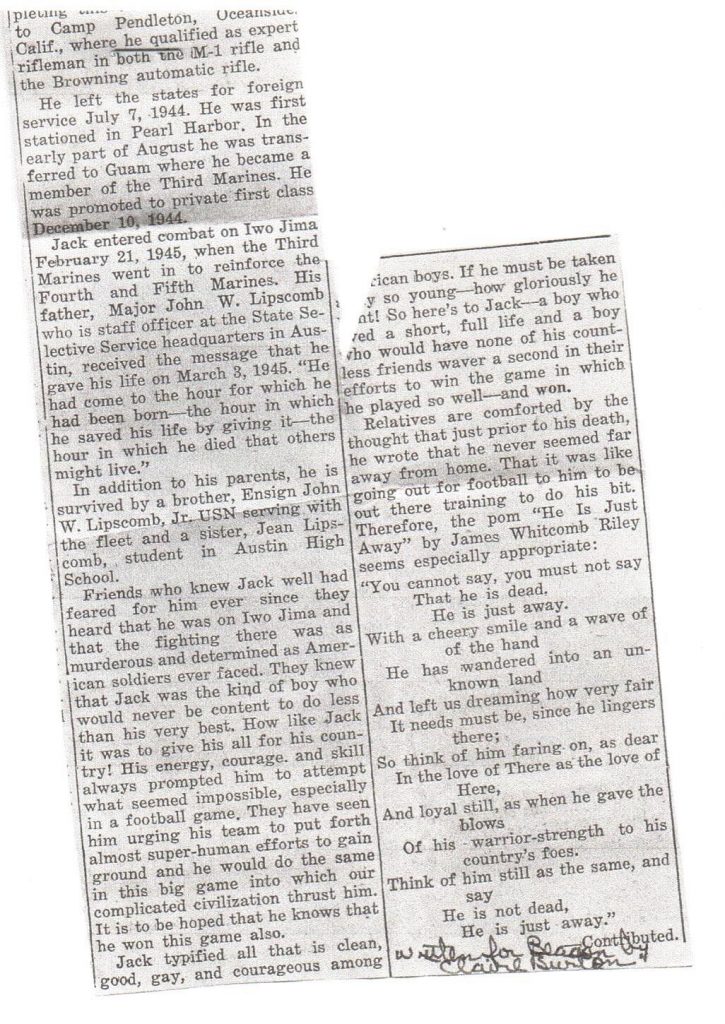

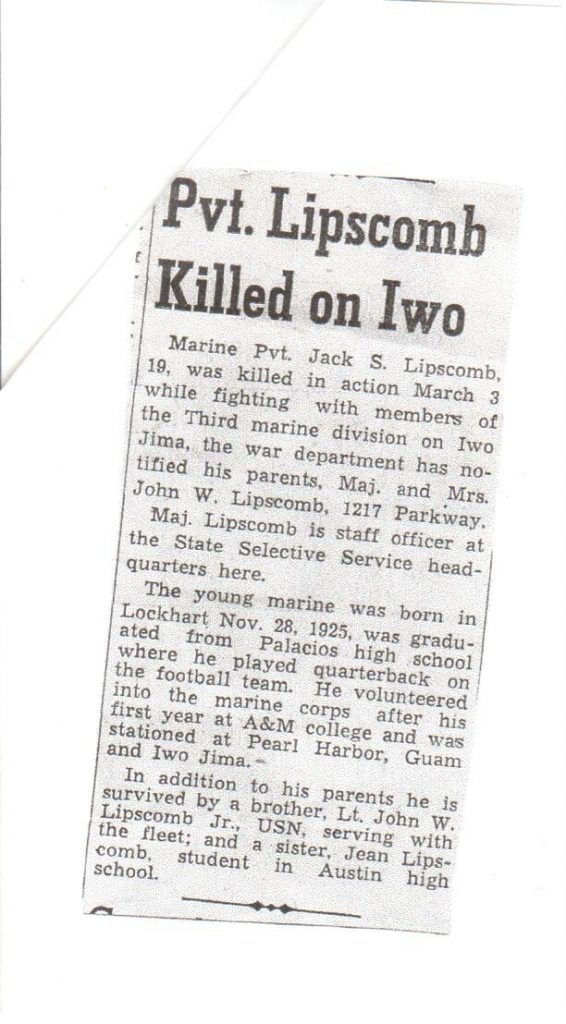

Lt. Pearson was blown free of the plane as it exploded. He had chuted up, and although badly battered, survived. Cameras were mounted in various aircraft to record bomb strikes and anti-aircraft sites. In this instance, Tommy’s B-17, aircraft number 44-6027, was photographed falling out of the sky. Lt. William Hoyer and seven other crewmen all died a fiery death high over Germany.

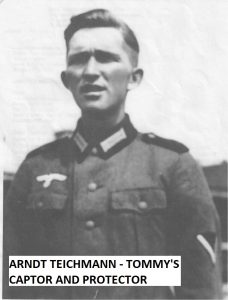

Things got even more interesting when Tommy hit the ground. A welcoming committee of angry German farmers armed with scythes approached him as he landed in a hay field. It looked as if he would be chopped to pieces. He was rescued by someone his bombs had intended to kill – a German soldier. Lt. Arndt Teichmann (shown here as he appeared in 1939) waved off the farmers with his weapon and took the relieved tail gunner into custody. . (Arndt Teichmann would later be captured by the Russians and somehow survive the hell of Stalin’s gulag, coming home in 1948).

Tommy was put in a farmer’s child’s playhouse, and Lt. Pearson, much the worse for wear was then brought in. Lacerated on his face and head, he also probably had broken ribs.

His captors were gentle. He was given some bread and margarine, and a bit of sausage. He asked for water in English, and instead was given a glass of beer.

Tommy was first taken to Nobliz, a Luftwaffe airfield. Then to Wetzler, where German intelligence officers interrogating him. “Hell, they knew more about our organization than I did. I just told them I was a new crewman.” The interrogation did not last long. The Germans knew crewmen didn’t have a lot of secret information to impart. The Germans took his electrically heated boots, and gave him a pair of shoes.

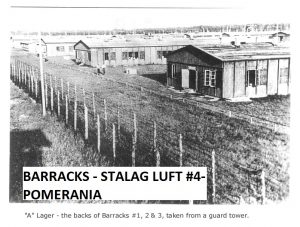

Eventually, Tommy arrived at Stalag Luft IV, a German Prisoner of War camp at Gross Tychow, Eastern Pomerania (now Poland). Inadequate shower facilities, heating, and clothing, spotty distribution of Red Cross parcels, bad food, overcrowding and poor medical attention were the order of the day. Escape was not remotely possible. Boredom reigned among the nearly 8000 American, and the thousand or so British, Polish, Czech, French and Norwegian POWs. The men slept in barracks designed for 160 men but holding 240 or more. Each barrack had a two-hole latrine, to be used only at night. During the day, POWs were required to use open-air latrines, with pits cleaned by Russian POWs. The daily ration consisted of bread bulked up with sawdust, a soup made with a mixture of potato, turnip, carrot, rutabaga, kohlrabi and horsemeat. The men also received cooked barley and millet once or twice a week. Most camp guards were benign, but some, with nicknames like Big Stoop, Green Hornet, and Squarehead, were known to be sadistic. Guards also would open Red Cross parcels and steal the best of the food before turning them over to POWs. Most of the POWs lost about between 15 and 20 pounds during captivity here. Upper respiratory infections, diphtheria, diarrhea, skin diseases, jaundice, meningitis were common. As bad as this was, at this stage of the war, the German populace in cities wasn’t faring much better.

used only at night. During the day, POWs were required to use open-air latrines, with pits cleaned by Russian POWs. The daily ration consisted of bread bulked up with sawdust, a soup made with a mixture of potato, turnip, carrot, rutabaga, kohlrabi and horsemeat. The men also received cooked barley and millet once or twice a week. Most camp guards were benign, but some, with nicknames like Big Stoop, Green Hornet, and Squarehead, were known to be sadistic. Guards also would open Red Cross parcels and steal the best of the food before turning them over to POWs. Most of the POWs lost about between 15 and 20 pounds during captivity here. Upper respiratory infections, diphtheria, diarrhea, skin diseases, jaundice, meningitis were common. As bad as this was, at this stage of the war, the German populace in cities wasn’t faring much better.

By early 1945 terror gripped Germans in their eastern provinces. The Soviet Union’s huge armies were driving for the heart of Germany, and revenge was their byword. While German soldiers fought desperately, civilians fled east. On February 6, 1945, some 8000 men imprisoned at Stalag Luft IV were told they could take what they could carry, and then were marched west as the camp was evacuated. The ordeal became known as “The Black March.” To the distant sound of Russian artillery in the east, over 8000 POWs began a forced march across East Prussia, Poland, and almost to Hamburg. The ordeal began in one of the coldest winters in European history, and lasted for nearly three months, on a trek nearly 600 miles long. Divided into sections, the prisoners zigzagged west.

Marched during the day, they were housed in barns, or in open fields. Some men became violently ill from drinking from fecal laden ditches. Pneumonia became endemic. Food usually consisted of potatoes which were sometimes eaten raw if no firewood could be found. The sick were often carried in farm wagons. In the camp, Tommy had become good friends with Floyd Jones, another B-17 crewman. Jones was a great scrounger. His skill proved very useful. Jones stole two bottles containing water for a farmer’s bees. He and Tommy drank the water, and kept the bottles to brew dandelion tea. They ate raw soy beans. On March 28, 1945 many of the men were crammed onto a freight train at Ebbsdorf, sixty to eighty to a boxcar. Many men were wracked by dysentery but the cars remained locked until the train arrived at Stalag 357 near Fallingbostel on the afternoon of March 30. Another move was ordered by the Germans for those fit to continue. Tommy, too sick to travel, was excused by an American doctor. Floyd wasn’t, so he made himself sick by smoking all the cigars in a Red Cross packet, and vomiting on the doctor’s desk. It worked. Five days later, British forces liberated the camp. The ordeal was over.

Tommy returned to Lockhart after the war, planning to go into construction like his father. Instead, he became an auto mechanic with the local Dodge / Plymouth dealership. In 1960 he purchased a service station property from Charlie Kelly on South Main, and transitioned into small engine repair. He married Opal Lackey on November 24, 1946. The couple was blessed with two daughters and a son. His daughters became school teachers, and his son, a trouble shooter for Waukesha Pearce. Opal passed away in 2007.

Tommy got his pilot’s license in 1949. Beginning in the early 80s, he built or partnered in ownership four airplanes. No longer an active pilot, he still has an ownership interest in a kit-built aircraft hangered at the Lockhart airport. And he still fixes lawnmowers and chainsaws on South Main. Drop by and say hi some time.

Tommy takes off in a kit built aircraft.

Notes: This story was published in the Lockhart Post Register and the Luling Newsboy Signal in August of 2014. Tommy passed away on January 7, 2016 at the age of 93. It was a privilege to have known him.