2nd Lieutenant Leshikar 1967

Chuck Leshikar 2018

T’ODON C. ‘CHUCK’ LESHIKAR

SILVER STAR RECIPIENT

SOLDIER’S MEDAL RECIPIENT

“You Might Say I Was In the Thick of It”

By Todd Blomerth

A few weeks ago, I had the privilege of interviewing Chuck Leshikar for this story. I planned on a couple of hours. It didn’t work out that way. Five hours after arriving at his home, the two of us were still talking. Well, mostly, I listened. To say Chuck Leshikar is an interesting human being is like suggesting that the sun is kind of warm.

Chuck Leshikar was born in Austin, Texas on January 10, 1946. The son of T’Odon Leshikar and Angel (Dexter) Leshikar, he was the second of four children. Chuck’s father, of Czech heritage from Smithville, was Bursar at the University of Texas. Raised in Austin, Chuck attended Austin High School, graduating in 1964.

Chuck enrolled in the University of Texas, intent on majoring in architecture. He flunked out. Vietnam was heating up and expecting to get drafted, Chuck decided he want to fly helicopters. Taking a preliminary flight physical that showed him to be a good candidate for Warrant Officer School and his wings, he enlisted. After basic training at Ft. Polk, Louisiana and Advanced Infantry Training at Ft. Ord, California, he was given another flight test and told that, no, he wasn’t going to get to go to flight school – his eyesight wasn’t quite good enough.

Chuck’s Plan B? To complete Infantry Officer Candidate School at Ft. Benning, Georgia. Then, he pinned on his 2nd lieutenant bars and signed up for additional schooling. In the mid-60s, everyone ‘knew’ you wouldn’t get sent to Vietnam if you had less that a year to go on your enlistment (That wasn’t necessarily so). He figured if he took enough schools, by the time he finished them, he’d have less than a year to go on his active duty commitment, and miss the usual one year tour in Southeast Asia.

Airborne School, Pathfinder School, Ranger School, Jungle Warfare School, 4.2” Mortar Platoon Leader School. Chuck completed them all. And still received orders for Vietnam. He’d finished all the training and still had one year and seven days left on his active duty hitch!

While at Ft. Hood he was temporarily assigned to the 1st Armored Division. Along with several thousand other soldiers, Lt. Leshikar was ordered to Chicago when riots broke out in the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination. The mayhem and violence left its mark on him, both internally and externally. During the riots his arm was sliced open with a rioter’s rat-tailed comb.

After a thirty-day leave, 1st Lieutenant Leshikar lumbered onto a flight from Bergstrom AFB to California. At Travis AFB he and others were packed onto a commercial flight. Destination – Saigon, Republic of Vietnam. “It was miserable,” Chuck recalls. “And to top it off, the in-flight movie was Will Penny, which was a really depressing story.”

Chuck had originally been assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade.

That brigade had taken its lumps and had been rotated to a relatively quiet area of Vietnam. Had he remained with the 173rd, it is probable he would never have seen the horrors and intensity of the combat about which I write. However, Chuck had volunteered for the 101st Airborne Infantry Division, which was assigned to one of the hottest combat zones in Vietnam.

That brigade had taken its lumps and had been rotated to a relatively quiet area of Vietnam. Had he remained with the 173rd, it is probable he would never have seen the horrors and intensity of the combat about which I write. However, Chuck had volunteered for the 101st Airborne Infantry Division, which was assigned to one of the hottest combat zones in Vietnam.

Chuck arrived in Vietnam on June 13, 1968 and was assigned to the 101st on July 1, 1968. He remembers July 1 ruefully. “That’s the same day the 101st Airborne Division became “Air Assault,” and went off “jump status.” This meant, among other things, his hope of receiving the much coveted “jump pay” was gone. After processing, he was flown to Hue, only recently retaken from North Vietnamese troops after bloody building to building fighting. From Hue, a jeep took him to LZ Sally, near the A Shau Valley. Despite his training as a mortar platoon leader, he was assigned as an infantry platoon leader in the “Delta Raiders,” D (Delta) Company, 2nd Battalion, 501st Airborne Infantry Regiment (D/2/501).

Vietnam’s A Shau Valley runs north and south for twenty-five miles. Flanked by two strings of heavily forested mountains, it was a key entry point into South Vietnam for North Vietnamese (NVA) soldiers and equipment, using the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Laos. The 101st’s areas of operation were in this hotbed of enemy activity. The daily log of Delta Company shows almost constant contact with the enemy. Search operations and reconnaisances in force were met with attempted ambushes. Sudden sniper and artillery fire from the well concealed enemy were encountered. Bunkers, weapons caches, were found and destroyed. 1st Lieutenant Chuck Leshikar found he was a natural leader of men. On August 18, 1968, his radio telephone operator (RTO) fell down a steep embankment and into a river. Chuck saved the man’s life, and was later awarded the Soldier’s Medal, awarded for “heroism not involving conflict with the enemy.”

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 2, 1926, takes pleasure in presenting the Soldier’s Medal to First Lieutenant (Infantry) T’Odon Charles Leshikar, Jr. (ASN: 0-5344035), United States Army, for heroism not involving actual combat with an armed enemy force in the Republic of Vietnam on 18 August 1968. First Lieutenant Leshikar distinguished himself while serving as a Platoon Leader in Company D, 2d Battalion, 501st Infantry. The Third Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Leshikar, was conducting a search and clear operation along the Song Bo River, Republic of Vietnam, and, because of the nature of the mission, it was necessary for half of the element to move through the water in order to locate any enemy weapons caches along the bank. Private First Class Robert L. Walker, the platoon radio telephone operator, stepped into a deep depression in the stream bed and, because of the weight and bulk of his equipment, was unable to remain above water. Observing the situation, First Lieutenant Leshikar, fully clothed and equipped, immediately jumped from the bank into the water to rescue the man. In the absence of First Lieutenant Leshikar’s quick action, Private First Class Walker undoubtedly would have drowned. First Lieutenant Leshikar’s personal bravery and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army.

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 2, 1926, takes pleasure in presenting the Soldier’s Medal to First Lieutenant (Infantry) T’Odon Charles Leshikar, Jr. (ASN: 0-5344035), United States Army, for heroism not involving actual combat with an armed enemy force in the Republic of Vietnam on 18 August 1968. First Lieutenant Leshikar distinguished himself while serving as a Platoon Leader in Company D, 2d Battalion, 501st Infantry. The Third Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Leshikar, was conducting a search and clear operation along the Song Bo River, Republic of Vietnam, and, because of the nature of the mission, it was necessary for half of the element to move through the water in order to locate any enemy weapons caches along the bank. Private First Class Robert L. Walker, the platoon radio telephone operator, stepped into a deep depression in the stream bed and, because of the weight and bulk of his equipment, was unable to remain above water. Observing the situation, First Lieutenant Leshikar, fully clothed and equipped, immediately jumped from the bank into the water to rescue the man. In the absence of First Lieutenant Leshikar’s quick action, Private First Class Walker undoubtedly would have drowned. First Lieutenant Leshikar’s personal bravery and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army.

Three days later, while operating six kilometers east of Fire Base T-Bone, Delta Company ran headfirst into the NVA. The Silver Star, the Armed Forces’ third-highest medal for gallantry, is awarded for singular acts of valor or heroism. The description of Lt. Leshikar’s actions, as part of the commendation, speaks for itself:

Three days later, while operating six kilometers east of Fire Base T-Bone, Delta Company ran headfirst into the NVA. The Silver Star, the Armed Forces’ third-highest medal for gallantry, is awarded for singular acts of valor or heroism. The description of Lt. Leshikar’s actions, as part of the commendation, speaks for itself:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918 (amended by an act of July 25, 1963), takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to First Lieutenant (Infantry) T’Odon Charles Leshikar, Jr. (ASN: 0-5344035), United States Army, for gallantry in action in the Republic of Vietnam on 21 August 1968. First Lieutenant Leshikar distinguished himself while serving as Platoon Leader with Company D, 2d Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. First Lieutenant Leshikar was leading his platoon on a search and clear operation in mountainous jungles near the city of Hue, Republic of Vietnam, when it made contact with an undetermined sized enemy force. He immediately deployed his men and moved with his weapons squad under the increasing volume of automatic weapons and small arms fire to within twenty-five feet of the fortified enemy position. By successfully directing the fire of this element, he enabled another squad to begin maneuvering against the enemy in an attempt to flank the position. When the weapons squad was pinned down by sniper fire, First Lieutenant Leshikar crawled across an open spot in the trail and became the primary target of the enemy riflemen as he closed on their position. He then engaged the enemy with effective supporting fire, allowing another of his men to successfully eliminate the snipers with hand grenades. First Lieutenant Leshikar returned to his men and discovered several members of his platoon were wounded and lay directly in the line of fire. He again directed the fire of his men, while under direct enemy fire, and made possible the evacuation of the injured. First Lieutenant Leshikar carried one of the more seriously wounded to the rear. Even though he was wounded himself during the initial confrontation, First Lieutenant Leshikar refused medical evacuation, and again moved forward to the front lines. He then continued to lead the advance of his platoon by constantly moving from position to position, directing and giving encouragement to his men, while continuing to maintain accurate artillery fire support. The enemy retaliated by firing an intense barrage of rocket propelled grenades, which forced the friendly troops to withdraw. First Lieutenant Leshikar remained behind, covering the withdrawal of his men and directing the fire of helicopter gunships into the enemy positions, dangerously close to his location. First Lieutenant Leshikar’s personal bravery and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army.

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress July 9, 1918 (amended by an act of July 25, 1963), takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star to First Lieutenant (Infantry) T’Odon Charles Leshikar, Jr. (ASN: 0-5344035), United States Army, for gallantry in action in the Republic of Vietnam on 21 August 1968. First Lieutenant Leshikar distinguished himself while serving as Platoon Leader with Company D, 2d Battalion, 501st Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. First Lieutenant Leshikar was leading his platoon on a search and clear operation in mountainous jungles near the city of Hue, Republic of Vietnam, when it made contact with an undetermined sized enemy force. He immediately deployed his men and moved with his weapons squad under the increasing volume of automatic weapons and small arms fire to within twenty-five feet of the fortified enemy position. By successfully directing the fire of this element, he enabled another squad to begin maneuvering against the enemy in an attempt to flank the position. When the weapons squad was pinned down by sniper fire, First Lieutenant Leshikar crawled across an open spot in the trail and became the primary target of the enemy riflemen as he closed on their position. He then engaged the enemy with effective supporting fire, allowing another of his men to successfully eliminate the snipers with hand grenades. First Lieutenant Leshikar returned to his men and discovered several members of his platoon were wounded and lay directly in the line of fire. He again directed the fire of his men, while under direct enemy fire, and made possible the evacuation of the injured. First Lieutenant Leshikar carried one of the more seriously wounded to the rear. Even though he was wounded himself during the initial confrontation, First Lieutenant Leshikar refused medical evacuation, and again moved forward to the front lines. He then continued to lead the advance of his platoon by constantly moving from position to position, directing and giving encouragement to his men, while continuing to maintain accurate artillery fire support. The enemy retaliated by firing an intense barrage of rocket propelled grenades, which forced the friendly troops to withdraw. First Lieutenant Leshikar remained behind, covering the withdrawal of his men and directing the fire of helicopter gunships into the enemy positions, dangerously close to his location. First Lieutenant Leshikar’s personal bravery and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army.

In mid-October 1968, the Delta Raiders were operating in a rugged and mountainous area They advanced on a sharp ridgeline, eventually dubbed Blue Falcon Ridge, they were met by murderous NVA fire. During the two day battle, the enemy hit the company with one of the heaviest mortar attacks he experienced in Vietnam. At dusk, a resupply helicopter arrived. Unable to land because of the tight perimeter, its crew threw out food and ammunition and began to ascend when it was hit by an RPG. The helicopter exploded and “it fell over the side of the hill in flames,” wrote Chuck. Some of what he saw was heartbreaking:

The medevacs came out and we were trying to get the co-pilot on board. He had suffered a severe and very mangled right leg, it was just hanging on by threads. He had lost all of his finger tips and was burned over quite a bit of his body. I will never forget standing on that ridge line to hold a strobe light to guide the helicopter in with. I was a standing target for all to see. The helicopter hovered above us with its spot light shining down on us, the wind from the blades whipping around us. It seemed to be a dream. All the tragedies of that day were around us. It was if I was watching the twilight zone. I was immediately returned to reality when I heard an AK-47 fire three rounds. I knew what was about to happen and it did. The mortar tube started firing again. Again, I heard three shots and the mortar rounds shifted to the other side of the ridge line. The NVA were adjusting mortar fire on us as we tried to medevac our wounded Delta Raiders.

The medevac lowered the basket and the pilot was placed in it and as it was going up one of the other men who had been on the helicopter walked up to me and asked, “Sir, am I very bad/” I looked at him and said, “No, you’re not hurt very bad at all. You’ll be okay.” And the young man looked at me and said, “Sir, do you know who I am?” And I looked at him and said, “No, I don’t.” The man was burned all over his face, had all of his hair gone and was burned pretty bad. I was trying to comfort him and tell him that he was not very bad when he informed that he was SGT Frank Wingo, who I knew very well but I couldn’t recognize because of the extent of the injuries and burns. It caught me totally off guard when he told me his name. That moment is something that I’ve thought over the years….I can’t keep from thinking about how he must have felt – that his injuries were so bad that I didn’t recognize him. I wanted to do something, but was totally unable to. I felt helpless and that I should been able to make it all right – all of it – the burns, my failure to recognize him –everything. This haunts me still. (Excerpt from Delta Raiders, Southern Heritage Press, 1998, The Days of Blue Falcon Ridge, by Chuck Leshikar).

In January 1969, Chuck became Echo (E) Company Commander. In May of 1969, some of the 101st units were involved in the protracted and deadly assault on Hill 937, or what became known as Hamburger Hill. The seemingly pointless extraction of blood from Americans, and the ensuing press coverage of this encounter with well dug in NVA, overshadowed an almost equally deadly battle.

While the battle raged for Hamburger Hill, Chuck’s company – a combat support unit – was in support of artillery and other 101st Airborne units securing the top of a remote hill dubbed Firebase Airborne. “It was the roughest territory I ever saw,” Chuck recalls. Upon approaching the hilltop, the helicopter carrying him and others was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade in the tail boom. “I was thrown out of the chopper from about fifteen feet up,” he recalls. A defensive perimeter was constructed, and the Americans dug in. The firebase came under increasing sniper fire. E Company had ground surveillance radar, and a reconnaissance platoon. The radar and the recon both were telling 1st Lt. Leshikar that the enemy was about to hit the firebase, and hit hard. “I told the S-3 [operations officer] that we were about to get overrun,” Chuck recalls. “I was ignored.”

In the early morning hours of May 13, 1969, that is exactly what happened. Stationed with his RTO near an artillery battery, he fought for his life. “Three enemy ended up in my foxhole. You do what you have to, to survive.” By morning, the NVA had disappeared. “They had no intention of taking the firebase. Their intention was to damage us and leave,” he recounts. Some areas of the

Chuck’s photos of artillery firing at FB Airborne just hours before the night attack

Chuck’s photos of artillery firing at FB Airborne just hours before the night attack

firebase were held only after hand-to-hand fighting, and artillery firing deadly “beehive” rounds directly at the oncoming enemy.

The U.S. Military Assistance Command Vietnam’s truncated information provided to the press of ‘significant events …during May 1969’ cannot begin to describe the hell of May 13, 1969:

III MAF (THUA THIEN PROV) – At approx 0330, an elm of the 3rd Bde, US 101st Abn Div (AM) at a fire spt base 27 mi SW of Hue rec a gnd atk fr an unk size NVA force. The en atkd fr several dirs, empl hv SA & auto wpns fire along with RPG. The trps dir organic wpns & point blank arty fire at the atkg en. No en were reptd to have pent the peri & contact was lost at an unreptd time. Res: 31 NVA soldiers kd. US cas were 25 KIA & 51 WIA. 9 I/Wpns & 1 CSW was cptrd.

Carlton Meyer’s Lost Battles of Vietnam –http://www.g2mil.com/lost_vietnam.htm – describes the incident more honestly:

- Firebase Airborne Overrun- There are several short, vague accounts about how this artillery firebase was overrun on May 13, 1969. One veteran believes it was bait to draw the NVA into combat. VC sappers slipped inside its weak defenses and exploded the artillery ammunition dump, killing a dozen and causing confusion. The NVA swept through the base at night killing and wounding most defenders and destroying its big guns. Many Americans managed to hide until the NVA left before dawn, so the base was never officially captured. However, it was wrecked and later abandoned.

Along with the Silver Star and Soldier’s Medal, Chuck was awarded the Purple Heart and three Bronze Stars.

At the end of his tour in Vietnam, 1st lieutenant Leshikar reverted to Reserve status, joining a Texas Army National Guard Airborne unit while re-enrolling and completing his college degree. He attended Jumpmaster School at Ft. Benning, completed the Advanced Officer Branch Course by correspondence, fully intending to continue in the military. It was not to be. The U.S. Army Reserve was glutted with officers and there were no positions available, unless you were willing to “drill for points” only, in hope of one day getting a paid position. It was time to move on to other things.

In 1975, Chuck’s life took a dramatic turn. Walking into Austin’s Scholz Garden, he eyed a beautiful young lawyer. It was love at first sight. “My single days are over,” he thought. “I just knew I was going to marry her.” He and Nancy Burrell were married at Hyde Park Presbyterian Church on January 31, 1975.

Chuck became a CPA and eventually had his own company. He also developed a software program for bottle distributors. “I found out I was good with computers.” But, he was traveling all the time, so in 1989 he sold his company, and he and Nancy purchased their Caldwell County property. Unable to stay idle, he and a cousin purchased a commercial flooring business. He retired the second time in 2004. Nancy, after a legal career in both the private and public sector, also retired.

PTSD – for years, Chuck didn’t give much credence to its existence. After all, he’d come through the horrors of Vietnam unscathed mentally. Or so he thought. In the late 1990s, Chuck’s world went upside down. Nearly thirty years after the combat he’d survived, PTSD struck him down with a vengeance. Even now, Chuck’s voice changed dramatically when describing PTSD’s effect upon him and his family. “Once it hits you, it doesn’t go away.” Clinical treatment, counseling, and support got him through PTSD’s tornado-like havoc. He feels blessed that there were resources available, and that he took the often extremely painful steps needed, to overcome PTSD’s potential life-destroying effects.

The Lesihkars have two grown children. Son T.C. Leshikar III is a tax partner with Price Waterhouse. Daughter Jamie uses her skills as an excellent horsewoman to use those remarkable animals with autistic children and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder sufferers.

Chuck and Nancy share their property with two longhorn steers (“Butch” and “Cassidy”) and a bull aptly named Ferdinand and 15 longhorn cows. Chuck is an active member of The Single Action Shooting Society, the organization that organizes and sanctions Cowboy Action Shooting competitions. His interest is this type of competition gave Chuck the idea of creating his own Western town. Chuck’s Agarita Ranch sprouted a frontier town, complete with saloon, hardware store, and bordello. Carriage races, cowboy shooting, and wedding receptions, were just part of the Old West created by Chuck. He recently sold this property, but has no end to interests, primarily involving military history.

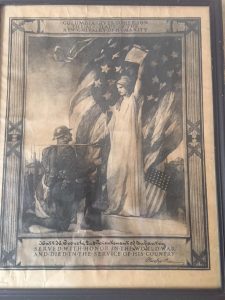

With a passion for military and American history, his collection of World War I artifacts is eye-opening. Photos of long-forgotten Doughboys line walls. I asked Chuck if any of the photos are of his family. “No,” he replied. “I’ve found them in garage sales and antique shops. It seems to me that they deserve some respect, so I gave them a home.” Complementing the photos are rare uniforms, diaries, and accoutrements of American soldiers of the early 1900s and World War I.

Next time you see Chuck, be sure to thank him for his service to his country. A simple acknowledgment of his efforts is most richly deserved.

Complete WWI American infantryman uniform

1913 American artilleryman’s saddle and gear

Chuck with doughboy’s WW1 Diary

Before the Purple Heart if wounded, you received this

NOTE: After publishing this, I visiting with Chuck again. “It’s funny what comes back to you,” he told me. “And what, at the time, we thought was either funny, or that could have killed us, that we didn’t think much of at the time.”

- He recalls being in contact with the enemy and calling in fire support from the old battlewagon, the USS New Jersey, sitting off the coast. The naval gunners didn’t take into account the changes in elevation. They let look with the ship’s huge guns, only to have the shells fall the WRONG side of the hill they were dealing with. Fortunately, the impacts and explosions were 500 meters away and no one was hurt. “Cease fire, cease fire,” was quickly shouted into the radio.

- While at a firebase, or location of some kind – i forgot which – someone commenced firing. The enemy was spotted on a LZ. Hopping into a LOACH (small spotter helo), he and others proceeding to get airborne and open fire on enemy. All of a sudden, the NVA opened up with a 12.5mm (.50 caliber) anti-aircraft gun. The pilot banked the helo, and took a round into the armored seat. The round extruded (but fortunately didn’t go all the way through), injuring the pilot. The pilot’s only worry: “Now I’ve got to tell my momma I got shot in the ass.”