JOHNNY SIEMERING

“WE BUILD – WE FIGHT” – A SEABEE ON SAIPAN

By Todd Blomerth

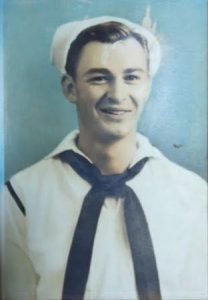

Johnny Siemering is 93 years young. Until his knees started giving him fits, you would not find him at home on Friday or Saturday nights – he would be dancing at a Hermann Sons function, or at a Community Center somewhere in the area. As it is, he is sharper than folks half his age. His love of life is infectious – spend a few minutes with him and you find yourself smiling with one of the most delightful persons in Caldwell County – of any age.

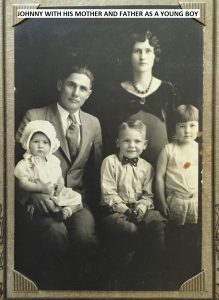

,Johnny was born in Maxwell, Texas in 1921. His parents, John August Siemering and Henrietta (Wink) Siemering were of German heritage. John August farmed with mules on 112 acres, and Henrietta taught school. Johnny was the oldest of five children. His sisters were Doris (Colgin) and Helen (Schmidt). His brothers were James or Jimmy, and Robert. Helen and Jimmy live in Creedmoor and Uhland, respectively. Doris and Robert have passed away.

,Johnny was born in Maxwell, Texas in 1921. His parents, John August Siemering and Henrietta (Wink) Siemering were of German heritage. John August farmed with mules on 112 acres, and Henrietta taught school. Johnny was the oldest of five children. His sisters were Doris (Colgin) and Helen (Schmidt). His brothers were James or Jimmy, and Robert. Helen and Jimmy live in Creedmoor and Uhland, respectively. Doris and Robert have passed away.

Johnny attended school in Maxwell, and graduated from high school in the 11th grade, which is as far as secondary school went in the late 1930s. The Siemering family rarely made it into town. There was too much work to be done, and there was very little money. He, Ellis Clark and other friends would on Sunday head to the Blanco River to swim, and then roast ears of corn. It was a simpler time.

After graduation, Johnny attended a six week farming program at Southwest Texas Teachers College, and then went to work at the Luling Foundation Farm. He has fond memories of his three years working there. Walter Cardwell Sr. was the Farm’s general manager. There were four departments – poultry, beef, farm and dairy – and he worked in all of them during his tenure. He lived in one of the bunkhouses. “We weren’t paid much, I think it started at $21 a month along with room and board, but the food was great.” Edgar B. Davis even roomed in one of the bunkhouses during one of his periods of financial difficulty. The learning experience under supervisors Mr. Prove, Mr. Tilley, and the veterinarian Dr. Redmond proved invaluable. He has fond memories of working with the Jersey cows, and the special treat of drinking the Foundation Farm’s delicious chocolate milk!!!!

Johnny was working for the Luling Foundation Farm when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. He first tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps to become an aviator, but slight color blindness prevented that. So he volunteered for the newly created Naval Construction Battalions (“Seabees”). Initially, the average age of a Seabee was 37 years, because of the emphasis on men experienced in construction trades. Although much younger than the average, Johnny had substantial training and experience that made him a perfect fit for his new role as a Seabee. The U.S. Navy’s succinct description of the Seabees’ contribution to the defeat of the Axis powers doesn’t begin to reflect the admiration of the Marines who served with them in the Pacific:

More than 325,000 men served with the Seabees in World War II, fighting and building on six continents and more than 300 islands. In the Pacific, where most of the construction work was needed, the Seabees landed soon after the Marines and built major airstrips, bridges, roads, warehouses, hospitals, gasoline storage tanks and housing.

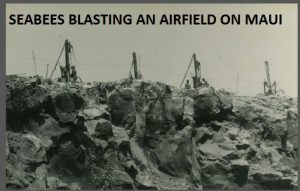

The Seabee Construction Battalion, usually comprising around 1100 men, was made up of four companies, along with a headquarters section with support personnel such as storekeepers, cooks, and medical staff. Reporting for training in December, 1942, Johnny was assigned to the 39th Construction Battalion. He did his basic training at Norfolk, Virginia. The Virginia winter weather was bitter, and he recalled the mostly southern trainees huddling under insufficient blankets as they tried futilely to get warm in the camp’s tents at night! The 39th moved to the new Seabee base at Port Hueneme, California, and then was shipped to Hawaii. The unit arrived at Maui on September 23, 1943 and for the next 10 months constructed airfields at Kahului. The rocky terrain proved a test of the Seabees’ abilities. Johnny remembers 100 train car-loads of dynamite needed to blast out the airfields. Johnny wanted to be a part of the construction but was assigned as a guard, which he hated. Happily, he was re-assigned as a truck driver hauling grease and lubrication to construction equipment at construction sites.

at Norfolk, Virginia. The Virginia winter weather was bitter, and he recalled the mostly southern trainees huddling under insufficient blankets as they tried futilely to get warm in the camp’s tents at night! The 39th moved to the new Seabee base at Port Hueneme, California, and then was shipped to Hawaii. The unit arrived at Maui on September 23, 1943 and for the next 10 months constructed airfields at Kahului. The rocky terrain proved a test of the Seabees’ abilities. Johnny remembers 100 train car-loads of dynamite needed to blast out the airfields. Johnny wanted to be a part of the construction but was assigned as a guard, which he hated. Happily, he was re-assigned as a truck driver hauling grease and lubrication to construction equipment at construction sites.

As 1944 wore on, the Battalion’s men knew inevitably that it would be re-assigned to a combat area. However rumors flew that, no, they were going to be sent back to the mainland. Then reality reared its head. In July the Battalion got word it was going to be shipped out to some Pacific island. The Battalion moved to Pearl Harbor on Oahu in late August, and underwent some grueling but thankfully shortened Marine training. Originally scheduled for Guam, the 39th was re-assigned to Saipan. The Battalion’s men spent miserable shipboard time sailing to Saipan. Too hot to sleep below decks, Johnny and others would drag mattresses onto ship decks to try to get some rest. He vividly remembers seeing the devastation of several of the Marshall Islands resulting from the U.S. invasions of those Japanese-held islands.

The U.S. Marines landed on Saipan beginning on June 15, 1944. Met with fierce resistance, the island was not declared “secured” until July 9, 1944. Declaring an island secure did not ensure that there were no longer enemy on the island – rather, that ‘organized resistance’ had ended. The 39th Construction Battalion began embarking on September 7, 1944 at Pearl Harbor, and it arrived at Saipan on September 30, 1944.

The U.S. Marines landed on Saipan beginning on June 15, 1944. Met with fierce resistance, the island was not declared “secured” until July 9, 1944. Declaring an island secure did not ensure that there were no longer enemy on the island – rather, that ‘organized resistance’ had ended. The 39th Construction Battalion began embarking on September 7, 1944 at Pearl Harbor, and it arrived at Saipan on September 30, 1944.

Several other Battalions were already there, some having gone ashore with the Marines on June 15th. In the words of CMD David Moore (Ret), a Seabee who was in that early group, “The Seabees gained the respect of the Marines with their ‘can do’ attitude. They built whatever the Marines needed – roads, water supplies, barracks, fuel storage, piers, airfields and many more. “

While missing the horrors of the landing, the 39th’s men still were witness to the physical and human devastation visited upon the island and its people. The 39th Construction Battalion would remain on Saipan for the remainder of the War.

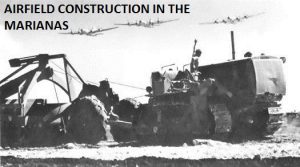

Given the dicey situation with hidden Japanese defenders still holding out, the Seabees were required to carry M-1 carbines. Saipan (along with Tinian and Guam) provided the US Army Air Forces with the bases within the range for the massive airstrikes against the Japanese home islands needed to subjugate the Japanese Empire with the new B-29 Superfortress. With its huge bomb load and fuel load, it needed long runways to reach the speeds necessary to lift off for the nearly 3000 mile round trip bomb run to Japan. Five large runways were constructed on the three islands. The Americans also constructed a large radar station on Saipan’s highest point. Johnny’s time on Saipan stirs both good and bad memories. His best memories were of helping his fellow Seabees and the marines and soldiers on the island. The construction battalions were instrumental in creating fresh water showers. Until that time, troops had to endure the misery of tropical heat and bathing in sea water. Johnny, by now a Machinist Mate 3rd Class, was instrumental in building an ice machine. He drove a truck providing supplies to construction crews on the island. He became legendary for his hauling ice to the heat prostrated work crews, particularly at the radar station.

Johnny’ service as a Seabee contributed to a proud tradition. Again, quoting from the Navy’s history:

Although Seabees were only supposed to fight to defend what they built, such acts of heroism were numerous. In all, Seabees earned 33 Silver Stars and 5 Navy Crosses during World War II. But they also paid a price: 272 enlisted men and 18 officers killed in action. In addition to deaths sustained as a result of enemy action, more than 500 Seabees died in accidents, for construction is essentially a hazardous business.

The 39th Construction Battalion was inactivated on September 28, 1945, and Johnny came home that November. In 1946, Johnny married the love of his life, Olice Dale Bible, whose brother George, a Marine, had died on Guam. Olice had first met Johnny when she was 13 and he had come to her family’s house in Martindale on a double date. Spotting him in the livin g room, she immediately fell in love with him, but would have to wait until after the war to begin dating her husband-to-be. They had 61 wonderful years together. Olice died in 2007. The couple was blessed with three daughters, Ginger (Hughes), Cathy (Gideon), and Peggy (Germer). Cathy passed away in 2000. They were also blessed with many grandchildren. And friends? There are too many to count.

g room, she immediately fell in love with him, but would have to wait until after the war to begin dating her husband-to-be. They had 61 wonderful years together. Olice died in 2007. The couple was blessed with three daughters, Ginger (Hughes), Cathy (Gideon), and Peggy (Germer). Cathy passed away in 2000. They were also blessed with many grandchildren. And friends? There are too many to count.

Initially working for the Harry Schawe gin, he then went to work for Lockhart’s Goodyear dealership after the war. He narrowly missed being killed in 1965 when a truck tire rim blew off, crushing his left leg. Dr. Tom Connolly rigged up a traction apparatus at the Lockhart Hospital and for six weeks Johnny lay in traction as weights were adjusted over his tractioned leg. Miraculously, his leg was saved. Even more miraculously, he walks without a limp even today.

Johnny went into full time farming after recovering from the explosion. He farmed milo, cotton and corn, and raised cattle until retiring. Retirement did not in any way mean that he retired from life. Johnny’s life is filled with family and friends. He was raised in Ebenezer Lutheran Church in Maxwell, and continues as an active member.

Tell him thanks for his service, next time you see him. That is, if you can catch up with him.

Clark Elwell’s School Project Proudly Telling of His Hero’s War Service

(Thanks to John Moore, son of CMD David Moore (deceased) for his kind permission to use quotes from his father’s story of the Seabees on Saipan)