This year marks the 60th anniversary of the beginning of the Korean Conflict. It has been called our ‘forgotten war’, although recent efforts have been made to inform an American public of what it was all about. These articles are a small effort in that direction.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the beginning of the Korean Conflict. It has been called our ‘forgotten war’, although recent efforts have been made to inform an American public of what it was all about. These articles are a small effort in that direction.

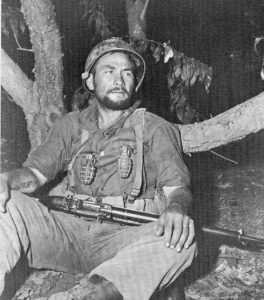

Exhausted GI

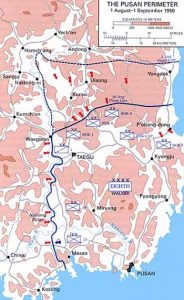

Pusan Perimeter

USMC Lt. Ike Fenton

As North Koreans pushed south, the US and South Korean armed forces (ROK) realized very quickly that there was only so much land they could trade for time. Re-supplying troops through the only port of Pusan in a shrinking perimeter crowded with hundreds of thousands of refugees interspersed with North Korean infiltrators was a daunting logistical nightmare.

As Far East commander in chief, General Douglas MacArthur oversaw all operations on the Korean Peninsula. The commander on the ground was General William Walker, who commanded the 8th Army. MacArthur in Japan, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff stateside hurried additional troops to the front. Ships were loaded out of Japan and the US West Coast with men, M26 Pershing tanks, heavy artillery, and ammunition. Carriers were loaded with A4D Skyraiders and F4U Corsairs. P-51s and other combat aircraft were re-located to Korea from Japan.

The retreat did offer some rays of hope – but not many. Logistically, the communist North Korean armed forces (KPA) was far from its base of supply in the North. The shrinking perimeter in the southeastern corner of the peninsula let the defenders draw closer to their supply bases while also narrowing the area they had to defend.

The quality and cohesiveness of most of the troops arriving at the port of Pusan improved as well, although many companies still had green recruits. Some of those units marched directly from disembarkation to the front lines.

As it advanced south the KPA also became more vulnerable to US air power, which in a matter of weeks decimated the KPA air force. F4U Corsairs, P-51s, A4D Skyraiders and other WWII vintage aircraft created havoc with ground forces advancing in daylight. As a result, the KPA was forced to resort to moving and attacking at night.

North Korea’s leadership was painfully aware of Allied air superiority and its own stretched supply lines and mounting losses. The KPA needed to make a breakthrough quickly before a strong defensive line in southeastern Korea could solidify. The right (or east side) of the defensive line that became known as the Pusan Perimeter was defended by ROK with US naval and air support. The left (or west) side of the 140 mile perimeter was held by US Army divisions, and the US Army’s 5th Regimental Combat Team. Many of these units had repeatedly been outflanked by the swiftly moving KPA, until establishing a thin line of resistance along the Naktong River.

The First Provisional Marine Brigade of 6500 men and with a large number of officers and NCOs with World War II Pacific combat experience (like Lt. Ike Fenton) was rushed from California, and used to plug gaps all along the west side of the perimeter. The marines’ tenacity surprised the KPA, which had become used to brushing aside ground resistance easily during the initial stage of the invasion.

The conditions were horrific. Temperatures in the summer reached 112 degrees. Water was scarce. Relentless fighting caused huge casualties. Men who passed out from heat exhaustion were evacuated, resuscitated and sent back into the fight. Every fighter was needed to deal with ongoing human wave attacks by a now desperate KPA that was trying to squeeze out the Pusan pocket before US reinforcements arrived in strength.

The KPA 83rd Motorcycle Regiment was caught in open ground by a Marine Corsair wing, which annihilated it in what became known as the “Kosong Turkey Shoot.” It was the first major victory for the Americans.

As the Perimeter shortened, the KPA lost its ability to maneuver around defending forces, and often chose to make frontal attacks on US and ROK forces. The KPA infiltrating its crack 4th Division across the shallow Naktong River along the western edge of the perimeter and then hit that side of the perimeter – hard. The attack made inroads through the rugged hills east of the river in an area that became known as the ‘Naktong Bulge’. General Walker’s 8th Army headquarters at Taegu was threatened, as was the route between there and Pusan harbor. The bulge had to be eliminated. An initial attack by the Army was repulsed. General Walker ran out of patience. He told the Army 24th Division commander, “I’m giving you the Marine brigade, and I want this situation cleaned up-and quick!”

In vicious hand to hand fighting, the marines and soldiers of the 9th, 19th and 34th Infantry Regiments broke through. Supporting air attacks came so close to the lines that in some instances ejected shell casings from strafing fighters showered down on US troops. The KPA 4th Division was shattered and left over 1200 dead as it retreated from the bulge. Thanks to incredible teamwork, bravery, and air superiority the Americans won the day – barely.

By early September, and with more troops and equipment arriving daily, most of the Pusan perimeter lines stabilized. But not around Taegu. There, the First Cavalry Division fought off wave after wave of KPA assaults. If the KPA achieved a break-through, Taegu was doomed, as was the entire perimeter. Walker and his commanders were forced to put together scratch forces made up of tankers, engineers, and anyone else who could shoot a rifle. The soldiers held tenaciously.

As pressure on the line increased, the South Korean government relocated from Taegu to Pusan along with hordes of refugees. General Walker’s command post was within six hours of evacuation. If the perimeter failed, the only recourse was evacuation from the Korean peninsula. Apart from political costs, the wholesale slaughter of un-evacuated soldiers and civilians loomed as a horrific possibility.

The US Marine Corps’ contribution to the preservation of the Pusan Perimeter cannot be overstated. In the words of a British observer:

“The situation is critical, and Miryang [a town behind the Naktong Bulge on a main route to Pusan] may be lost. The enemy has driven a division-sized salient across the Naktong. More will cross the river tonight. If Miryang is lost…we will be faced with a withdrawal from Korea. I am heartened that the Marine brigade will move against the Naktong salient tomorrow. They are faced with impossible odds, and I have no valid reason to substantiate it, but I have the feeling they will halt the enemy…These Marines have the swagger, confidence and hardness that must have been in Stonewall Jackson’s Army of the Shenandoah. They remind me of the Coldstreams at Dunkirk. Upon this thin line of reasoning, I cling to the hope of victory.”

Historians now believe that had the KPA concentrated an attack on one point on the perimeter, it would have succeeded. Instead, it drained itself by attacking all along the line, bleeding itself dry in the process.

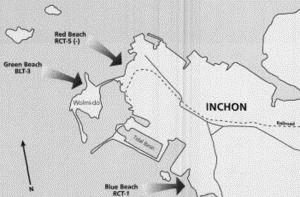

To turn the situation around, General MacArthur offered what appeared to be an insanely risky proposal: an amphibious landing at the port city of Inchon, west of the South Korean capital of Seoul, to take pressure off the Pusan Perimeter and take the invaders from behind. Inchon was a sleepy port and fishing town. A small harbor, mudflats, tidal surges and swift currents gave planners logistical nightmares. Additionally, Inchon was defended by the island of Wolmi-do. There would not be enough time to secure Wolmi-do and make landings on the mainland at the same high tide. The units hitting the beach on Wolmi-do would be on their own for 12 hours. American intelligence did not know how many KPA troops were defending the beaches and surrounding hills. MacArthur took the position that the very limitations argued for its usage. Who in their right mind would invade such a precarious position?

His plan was met with skepticism in Washington. In true MacArthur fashion, he did his best to put his operation in motion before the President and Joint Chiefs of Staff could veto it. While Washington vacillated, he presented the landings as a fait accompli. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that had Washington called off the attack, the invasion fleet would have had to turn around en route.

The KPA knew there was an amphibious landing in the works. The question was where. It was impossible to hide the preparations at Pusan and elsewhere. But they hoped to break through the US and ROK defenses before that happened. Kim Il Sung was warned by the Chinese of the danger of a landing at Inchon, but he scoffed at the possibility. As a result, the landing area remained poorly defended.

USS Valley Forge off Korea

Inchon Landings

The bombardment preceding the Inchon landing of September 15th was long and intense. Inchon’s island outpost of Wolmi-do received the brunt of the initial attacks due to its strategic importance. If not taken, KPA forces on Wolmi-do could enfilade landings on the mainland. Although new intelligence indicated that Inchon and Seoul were lightly defended because the KPA had sent experienced troops to reinforce the attacks around Pusan, this information was not entirely trusted.

USMC Lt. Baldomero Lopez Leads the Way. He is killed moments later

Street Fighting in Seoul

After Wolmi-do was secured, with little opposition, the main landings occurred. Troops and marines were forced to use scaling ladders to climb the sea walls. The landing was a complete surprise. The outmatched North Korean defense started to crumble. The Inchon landing was a success of huge proportions. It has been viewed as the pinnacle of General Douglas McArthur’s career. British historian Max Hastings calls it “MacArthur’s masterstroke.” Unfortunately, it also reinforced his already inflated ego, which later doomed him to professional downfall.

The army, marine and ROK attackers pushed inland. The KPA stripped 10,000 soldiers from the Pusan perimeter to meet the threat in their rear but were still out-numbered 5 to 1. As the Inchon forces approached Seoul, resistance stiffened. The capital was retaken only after bitter street fighting.

In the south, General Walker’s 8th Army awaited the Inchon landings. When the landings began it counterattacked. After a few false starts, the attacks succeeded, and dispirited KPA troops broke and ran. The North Koreans did not want to be caught between the two advancing forces. The ROK troops in the east end of the pocket pushed up the coast as the Inchon forces secured Seoul and pushed north across the 38th Parallel.

A great victory, which six weeks before seemed unthinkable, had just happened, and with surprisingly few casualties. But what to do next? Stop at the 38th Parallel, or continue north, liberating North Korea from the communists and unifying the peninsula? There was little or no resistance from the remnants of the KPA. Almost automatically, US and Allied troops followed the ROK army over that parallel in pursuit of the remnants of the KPA. Little thought was given by MacArthur or those in Washington to China’s threat to intervene in the war if the Allied troops approached the Chinese border. A disaster loomed.

(Bill Sloan’s The Darkest Summer [2009] has provided me with much information for this article. The Lt. Ike Fenton photo is by David Duncan, famous Life photographer.)

Next: The Chinese enter the war; Chosin Reservoir; Retreat; MacArthur fired.

THE_KOREAN_CONFLICT-PART TWO -FINAL w final corrections